Duane Hanson: the New Objectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 1987 CAA Newsletter

newsletter Volume 12. Number 2 Summer 1987 1988 annual meeting studio sessions Studio sessions for the 1988 annual meeting in Houston (February Collusion and Collision: Critical Engagements with Mass 11-13) have been planned by Malinda Beeman, assistant professor, Culture. Richard Bolton, c! 0 Ha,rvard University Press, 79 University of Houston and Karin Broker, assistant professor, Rice Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. University. Listed below are the topics they have selected. Anyaddi Art and mass culture: it is customary to think of these two as antagon tional information on any proposed session will be published in the Fall ists, with art kept apart to best preserve its integrity. But recent art and newsletter. Those wishing to participate in any open session must sub theory has questioned the necessity of this customary antagonism, and mit proposals to the chair of that session by October I, 1987. Note: Art many contemporary artists now regularly borrow images and tech history topics were announced in a special mailing in April. The dead niques from mass culture. This approach is fraught with contradic line for those sessions was 31 May. tions, at times generating critical possibility, at times only extending the reign of mass culture. It becomes increasingly difficult to distin Artists' Visions of Imaginary Cultures. Barbara Maria Stafford (art guish triviality from relevance, complicity from opposition, collusion historian). University of Chicago and Beauvais Lyons (print from collision. Has the attempt to redraw the boundaries between maker), University of Tennessee, Department of Art, 1715 Vol mass culture and art production been successful? Can society be criti unteer Blvd., Knoxville, TN 37996-2410. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects. Cambridge and London: M.I.T. Press, 2005; pp. 1-8. Text © Robert Hobbs The Beginnings of a Complex The problem seems to be how to connect without connecting, how to group things together in such a way that the overall shape would resemble "the other shape, ifshape it might be called, that shape had none," referred to by Milton in Paradise Lost, how to group things haphazardly in much the way that competition among various interest groups produces a kind ofhaphazardness in the way the world looks and operates. The problem seems to be how to set up the conditions which would generate the beginnings ofa complex. Alice Aycock Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs, 1977 In Book 11 of Milton's Paradise Lost, Death assumes the guise of two wildly dissimilar figures near Hell's entrance, each with an extravagantly inconsistent appearance. The first, a trickster, appears as a fair woman from above the waist and a series of demons below, while the second-a "he;' according to Milton-is far more elusive. It assumes "the other shape" that Aycock refers to above. 1 When searching for a poetic image capable of communicating the world's elusiveness and indiscriminate randomness, Aycock remembered this description of Death's incommensurability, which she then incorporated into her artist's book Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs. Although viewing death in terms oflife is certainly not an innovation, as anyone familiar with Etruscan and Greco-Roman culture can testify, seeing life's complexity in terms of this shape-shifting allegorical figure signaling its end is a remarkable poetic enlists images from the past and from other inversion. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture. -

Abstract Expressionism: a Concern with the Unknown Within.” in Robert Hobbs and Gail Levin

“Early Abstract Expressionism: A Concern with the Unknown Within.” In Robert Hobbs and Gail Levin. Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1978; pp. 8-26. Text © Robert Hobbs Early Abstract Expressionism: A Concern with the Unknown Within by Robert Carleton Hobbs Breakthrough! The term "breakthrough" is often used to assess a major accomplishment of an artist, the works in which he first achieves an undeniable advance. But what does a breakthrough really signify? What does an artist leave when he begins a new style? Is he really leaving, so to speak, one room, closing and sealing the door to it when he enters another? Or is he remodeling, expanding, or merely redecorating the room in which he exists? A major intent of this essay is to look closely at the rooms occupied by the Abstract Expressionists during their formative years, the enclosures pejoratively designated Surrealist-Cubist, in order to understand exactly what sort of quarters they inhabited before their acclaimed breakthrough. Moreover, the essay will examine these spaces, the ideas expressed in them and the artistic and literary sources supporting them. It will imply ways the later style is incorporated in the earlier one, for the development of the New York painters in the late 1940s was from the complex to the simple, from an admittedly conftated ambiguity typifying their work in the late thirties and greater part of the forties to the more condensed forms that remained the distinctive characteristic of their later style. The early paintings explain the later ones: they provide the key to interpreting the significant content that preoccupied the Abstract Expressionists. -

Museums and Their Objects.” in Robert Hobbs and Frederick Woordard, Eds

“Introduction, HUMAN RIGHTS/HUMAN WRONGS: Museums and Their Objects.” In Robert Hobbs and Frederick Woordard, eds. HumanRights/Human Wrongs: Art and Social Change. Iowa City: The University of Iowa Museum of Art, 1986; pp. 1-19. Text © Robert Hobbs INTRODUCTION HUMAN RIGHTS/HUMAN WRONGS: Museums and Their Objects ROBERT HOBBS Although museum staff members and the general public often ac cept the conventions of exhibiting art and producing catalogues as norms which are beyond question, I believe these conventions need to be challenged. I wish to begin this book by questioning assumptions about the inherent goodness of art, the great benefits to be derived from going to museums, the satisfying knowledge currently available about art, and the separation of art from the power struggles that seem to pervade all other aspects of life. Rather than providing an swers, this introduction will suggest ways that certain beliefs can and should be questioned. Museums and their publications often constitute a way of looking that is superimposed upon the visions of an individual artist to be come the societal work of art that we call culture. If we are to free art from the current mode of museum practice-which seems intent on embalming it in a mausoleum-and allow it to be a deeply felt re action to the world by a sensitive individual, then we have to look critically at museums and assess their attitudes about the role of art in contemporary life. THE MusEUM AS MAusoLEUM Largely a late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century creation, the art museum has been viewed as an arbiter of taste, a legitimizer of vanguard experiments, and a repository for art where one can go and look and be suspended in time. -

Felix Gonzalez-Torres's Epistemic

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CJP\26-3\CJP305.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-MAY-17 15:07 F ELIX´ GONZALEZ-TORRES’S ´ EPISTEMIC ART Robert Hobbs* Latin-American, gay, and AIDS positive, F´elix Gonz´alez-Torres seemed to be the perfect model for both the late 1980s and early ’90s culture wars, which emphasized sex and diversity. Because Gonz´alez- Torres’s life made him such an apt subject for addressing social and po- litical wrongs, many critics and art historians premiered both him and his art when discussing these hotly debated issues. But Gonz´alez-Torres himself regarded these personal matters separately from his epistemolog- ically oriented work. In an interview with fellow artist Tim Rollins, he discussed his desire to critique mainstream culture from within its struc- ture and accepted practice rather than serve as one of its pawns: “I love the idea of being an infiltrator. I always said that I wanted to be a spy . I don’t want to be the opposition because the opposition always serves a purpose . .”1 Because Gonz´alez-Torres understood the need to focus his energies within established art discourses rather than mounting attacks from the outside, his art, with its important epistemological and ontologi- cal innovations, places him in a direct line with such major twentieth- century artist-thinkers as dadaist Marcel Duchamp, minimalists Donald Judd and Robert Morris, and earth artist Robert Smithson. Although he often alluded to his partner, Ross Laycock, in a number of works, Gonz´alez-Torres straightforwardly presented a series of HIV- positive blood count charts with their gridded formats resembling the look of Minimalism, and drew on Latino festivals in his works consisting of strings of light bulbs and Caribbean d´ecor in his beaded curtains. -

Robert Hobbs Joseph Kosuth's Early Works

‘There is no world when there is no mirror’ is an absurdity. But all our relations, as exact as they may be, are of descriptions of man, not of the world : these are the laws of that supreme optics beyond which we cannot possibly go. It is neither appearance nor illusion , but a cipher in which something unknown is written – quite readable to us, made, in fact, for us: our human position towards things. This is how things are hidden from us. Friedrich Nietzsche A Selection of Early Works from the 1960s by Joseph Kosuth Sean Kelly Gallery 528 West 29 Street 212 239 1181 New York, NY 10001 www.skny.com “Joseph Kosuth’s Early Work” © Robert Hobbs, 2008 Joseph Kosuth’s Early Work by Robert Hobbs , The Rhoda Thalhimer Endowed Chair of American Art, Virginia Commonwealth University & Visiting Professor, Yale University Artworks . describe how they describe . What art shows in such a manifestation is, indeed, how it functions. Joseph Kosuth, “Intention(s),” Art Bulletin , 1996 With such pieces as ‘Glass Words Material Described’ and his One and Three series, Joseph Kosuth initiated the new artistic category, conceptual art. He conceived (or thought through) 1 these and other conceptual pieces in the fall of 1965 and had a few of them fabricated at that time, even though he was beginning his first year at New York’s School of Visual Arts (SVA) and was working with limited funds. Representing an intensification of Marcel Duchamp’s well-known preference for epistemology over ontology and a recognition of the profound importance of his notes, Kosuth’s extraordinary advance came two years before Sol Lewitt’s famous “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” was published in Artforum in June 1967, and three years before Lawrence Weiner started his widely recognized conceptually based practice. -

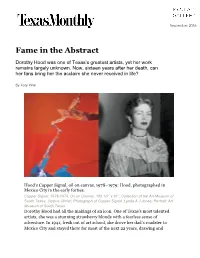

Fame in the Abstract

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs. -

Women of Abstract Expressionism

WOMEN OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM EDITED BY JOAN MARTER INTRODUCTION BY GWEN F. CHANZIT, EXHIBITION CURATOR DENVER ART MUSEUM IN ASSOCIATION WITH YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN AND LONDON Published on the occasion of the exh1b1t1on Women of Abstract Denver Art Museum Expressionism. organized by the Denver Art Museum Director of Publications: Laura Caruso Curatorial Assistant: Renee B. Miller Denver Art Museum. June-September 2016 Yale University Press Mint Museum. Charlotte. North Carolina. October-January 2017 Palm Springs Art Museum. February-May 2017 Publisher. Art and Architecture: Patricia Fidler Editor Art and Architecture: Katherine Boller Wh itechapel Gallery. London.June-September 2017 . Production Manager: Mary Mayer Women of Abstract Expressionism is organized by the Denver Art Museum. It is generously funded by Merle Chambers: the Henry Luce Designed by Rita Jules. Miko McGinty Inc. Foundation: the National Endowment for the Arts: the Ponzio family: Set in Benton Sans type by Tina Henderson DAM U.S. Bank: Christie's: Barbara Bridges: Contemporaries. a Printed in China through Oceanic Graphic International. Inc. support group of the Denver Art Museum: the Joan Mitchell Foundation: the Dedalus Foundation: Bette MacDonald: the Deborah Library of Congress• Control Number: 2015948690 Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts;the donors to the ISBN 978-0-300-20842-9 (hardcover): 978-0914738-62-6 Annual Fund Leadership Campaign: and the citizens who support the (paperback) Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). We regret the A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. omission of sponsors confirmed after February 15. 2016. This paper meets the requirements of ANS1m1so 239.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 8-2013 Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson Eric Saxon University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Saxon, Eric, "Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson" (2013). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SCIENCE FICTIONAL TRANSCENDENTALISM IN THE WORK OF ROBERT SMITHSON by Eric Saxon A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Marissa Vigneault Lincoln, Nebraska August 2013 ii SCIENCE FICTIONAL TRANSCENDENTALISM IN THE WORK OF ROBERT SMITHSON Eric James Saxon, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: Marissa Vigneault In studies of American artist Robert Smithson (1938-1973), scholars often set the artist’s early abstract expressionist and Christian iconographical paintings apart from the rest of his body of work, characterizing this early phase as a youthful encounter with the enduring legacy of abstract expressionism in the late 1950s to early 1960s as well as a temporary preoccupation with ritualized Catholic imagery. -

Robert Smithson: Sculpture

“Smithson’s Unresolvable Dialectics,” and “A Nonsite, Franklin New Jersey.” In Robert Hobbs. Robert Smithson: Sculpture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981; pp. 19-30, 105-108. Text © Robert Hobbs SMITHSON'S UNRESOLVABLE DIALECTICS Robert Hobbs A Plea for Complexity vision of a mirror looking at itself and becomes a signif icant image of reflexiveness. To a viewer acquainted Artists are not straightforward thinkers, even though with the Minimalist need to reduce sculpture to its abso they may be logical and concrete in their use of mate lute essence, even to the point of appearing more object rials. Artists think indirectly in terms of a medium. than sculpture, Enantiomorphic Chambers might be dis Whenever historians and critics consider themselves to tressing. While the piece does appear to be more object be doing an artist a service by tidying the peripheral mo than presence and does not seem to strain belief by sug rass of difficulties surrounding a work of art-unclear gesting anything more than the materiality of its constit meanings, possible uncharted courses of significance uent elements, there is something confusing about it. they do an artist a disservice because they recreate the Even though viewers face two obliquely angled mirrors, art, substituting in place of the difficult and even contra they do not see themselves. The enantiomorphic mirrors dictory work their own narrow, carefully reasoned, and make viewers feel disembodied and unreal as if they often clearly articulated point of view. With some the have been sucked into some new realm, maybe a fourth damage would not be permanent, but with Robert Smith dimension in which commonly understood space/time son, who constantly strived to conflate and expose the coordinates are no longer applicable.