Echo, Reverb and (Dis)Ordered Space in Early Popular Music Recording

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

His Master's Voice Double-Sided Records

PRICES OF " His Master's Voice Double-Sided Records THE ROYAL RECORD (R.E. 284) THEIR MAJESTIES THE KING & QUEEN. 10 in. Double-sided, 5/6. THE ROYAL RECORD (R.D. 837) H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES. 12 in. Double-sided 5/6. NURSERY Records-ORANGE Label (Serial Letters AS, 7-inch 1/6. (Each series of 6 records in album, 12/6. Decorated Album-with linen pockets -separate. 3/6.) PHYSICAL CULTURE Records.-Set complete in album, 12/-. Album and chart separate, 3/-. Se6al Colour of Label. 10-inch 112-inch e tter PLUM... 4/6 C ... BLACK 6/6 D ... RED 8/6 DB ... BUFFPALE 10/- DK GREEN 11/6 DM PALE BLUE... 13/6 DO WHITE 16/- DQ ... Unless otherwise stated "His .fasters Voice" Records should be played at a steed of 78. His .taster's Voice" hn.strz uta,,eons Speed Tester, shows instantly whether yo,rr motor is rnuznine correctly. "His Master's Voice" Records EVA PLASCHKE VON DER OSTEN & MINNIE NAST (with orchestral accompaniment) 12-inch double-sided Black Label. Ist ein Traum, kann nicht wirklich sein (Is it a dream ? truly I know not !)-Act 3 (" Der Rosenkavalier ") (In German) Richard Strauss D.1002 ... Mit ihren Augen voll Tränen (Those eyes filled with tears)-Act 2 ('" Der Rosenkavalier ") (In German)... Richard Strauss ... ... ... NEUES TONKÜNSTLER ORCHESTER 12-inch double-sided Plum I,abel C.1202 " Der Rosenkavalier "-Waltz, Parts 1 and 2 Richard Strauss DJ FR ROSENKA VALIER had such a sensational success in England last year that it was selected as the most suitable piece with which to open this year's season of Royal Opera at Covent Garden on May 18th. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Chris Connor Songlist Anita Oʼday Songlist

Please find below the extensive songlist that Kathy Kosins utilizes when selecting the repertoire for the “Ladies of Cool” show. ANITA OʼDAY SONGLIST PICK YOURSELF UP SWEET GEORGIA BROWN...PICK YOURSELF UP (1956) BUDDY BREGMAN HONEY SUCKLE ROSE NO MOON AT ALL...THIS IS ANITA...NORM GRANTZ (1955) AS LONG AS I LIVE TENDERLY WEʼLL BE TOGETHER AGAIN...ANITA SWINGS THE MOST (1957) WORLD ON A STRING…BAND...(HERB ELLIS/RAY BROWN/OSCAR PETERSON/JOHN POOLE) WHISPER NOT...DIVA SERIES (1955-1962) (VERVE) FOUR BODY AND SOUL…ANITA SINGS THE WINNERS (1958) IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU…INCOMPBRABLE (1960) I HEAR MUSIC LOVER COME BACK TO ME…TRAVLIN LIGHT (1961) TRIBUTE TO BILLIE GREEN DOLPHIN ST…BREAKFAST SHOW (1964) LIVE AT THE BASIN ST. WEST IN A MELLOW TONE MORE THAN YOU KNOW DO NOTHIN TILL YOU HEAR FROM ME…ALL THE SAD YOUNG MEN (1961) YOUʼD BE SO NICE TO COME HOME TO DONʼT MEAN A THING STREET OF DREAMS…VINE ST. LIVE (1991) CHRIS CONNOR SONGLIST ALL I NEED IS YOU...CHRIS CRAFT (1956) ALL ABOUT RONNIE...(1954) RELEASE (LATER OTHER RECORDINGS) LULLABY OF BIRDLAND (1953) ALONE TOGETHER (all from Portrait of Chris-1960) IF I SHOULD LOSE YOU HEREʼS THAT RAINY DAY IM GLAD THERE IS YOU I WISHED ON THE MOON (from Haunted Heart-----2001..@ Rudy Van Gelders) THEY ALL LAUGHED WITCHCRAFT COME RAIN OR SHINE (all from the two box set...” I Miss You So..1956 and Witchcraft 1959) All THE THINGS YOU ARE (FROM MAYNARD AND CHRIS…DOUBLE EXPOSURE) SATURDAY IS THE LONLIEST NIGHT OF THE WEEK (FROM NEW AGAIN...1987) ALL THE WAY.. -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia. -

Suggested Wedding Music

Suggested Wedding Music Bach-Gounod, Ave Maria Dekoven, O Promise Me Pachelbel, Canon in D Borodin, Polovetsian Dances Wagner, Bridal Chorus (Stranger in Paradise) Mendelssohn, Wedding March Grieg, Wedding Day at Troldhaugen Mouret, Rondeau Schubert, Ave Maria ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Franck, Panis Angelicus Handel, Hornpipe “Water Music” Handel, La Rejouissance “Royal Jewish Repertoire Fireworks” Hava Nagila Massenet, Meditation from Thais Hatikvah Gluck, Minuet from “Orpheus” Raisins and Almonds Purcell, Trumpet Tune Mazel Tov! Clarke, Trumpet Voluntary Ceremony Schubert, Ave Maria Y’did Nefesh Mozart, Rondeau Jerusalem of Gold Bach, Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Chorshat Ha’ekaliptus Bach, Air on the G String Hitragut Handel, Aria from Xerxes Erev Shel Shoshanim Vivaldi, Largo, from the Erev Ba Four Season Hana’ava Babanot English Folk Melody, Greensleeves K’var Achare Chatzot Molloy, Love’s Old Sweet Song Al Kol Ele Bond, I Love You Truly El Ginat Egoz Schubert, Serenade Dodi Li Gluck, Melody Dodi Li II Ivanovici, Waves of the Danube MacDowell, To a Wild Rose Bride and Groom Entrance Chopin, Etude No. 3 Od Yishama De Koven, Oh, Promise Me Od Yishama II Traditional, Believe Me, If All Those Yasis Alayich Endearing Young Charms Ose Shalom Bach, Sheep May Safely Graze Vay’hi Bishurn Melech Mozart, Alleluia Asher Bara Handel, Entrance, Queen of Sheba Y’varch’cha Liszt, Liebestraum Kozatske Grieg, I Love Thee (Ich Liebe Dich) and others…… Liszt, Liebestraum Tschaikowsky, Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet Barnby, O Perfect Love 1 Suggested Music for Weddin g Preludes and other Events Mozart Early Quartets Vocalise, Rachmaninoff Mozart, 3 Divertimenti Danse Des Mirlitons, Tschaikowsky Mozart, Sonate in D Bacarolle, Offenbach Beethoven Op. -

ANN ARBOR the Sixties Scene by Michael Erlewine

1 ANN ARBOR The Sixties Scene By Michael Erlewine 2 INTRODUCTION This is not intended to be a finely produced book, but rather a readable document for those who are interested in my particular take on dharma training and a few other topics. These blogs were from the Fall of 2018 posted on Facebook and Google+. [email protected] Here are some other links to more books, articles, and videos on these topics: Main Browsing Site: http://SpiritGrooves.net/ Organized Article Archive: http://MichaelErlewine.com/ YouTube Videos https://www.youtube.com/user/merlewine Spirit Grooves / Dharma Grooves Cover Photo of Me Probably By Andy Sacks or Al Blixt Copyright 2019 © by Michael Erlewine 3 ANN ARBOR Here are a series of articles on Ann Arbor, Michigan culture in the late 1950s and 1960s. It mostly some history of the time from my view and experience. I could add more to them, but I’m getting older by the day and I feel it is better to get something out there for those few who want to get a sense of Ann Arbor back in those times. I have edited them, but only roughly, so what you read is what you get. I hope there are some out there who can remember these times too. As for those of were not there, here is a taste as to what Ann Arbor was like back then. Michael Erlewine January 19, 2019 [email protected] 4 CONTENTS How I Fell in Love and Got Married ............................... 7 Ann Arbor Bars ........................................................... 16 Ann Arbor Drive-Ins.................................................... -

Æ•¦ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ—¶É— ´È¡¨)

茱莉·倫敦 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Feeling Good https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/feeling-good-5441384/songs Make Love to Me https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/make-love-to-me-17036594/songs Julie Is Her Name https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/julie-is-her-name-6308277/songs All Through the Night: Julie London Sings https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/all-through-the-night%3A-julie-london- the Choicest of Cole Porter sings-the-choicest-of-cole-porter-4729812/songs Lonely Girl https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lonely-girl-6671594/songs Sophisticated Lady https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sophisticated-lady-7563108/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/yummy%2C-yummy%2C-yummy- Yummy, Yummy, Yummy 8061142/songs London by Night https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/london-by-night-6671092/songs Julie...At Home https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/julie...at-home-17016537/songs Julie https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/julie-6307990/songs Your Number Please https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/your-number-please-8058901/songs Calendar Girl https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/calendar-girl-5019486/songs Easy Does It https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/easy-does-it-5331119/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/julie-is-her-name%2C-volume-ii- Julie Is Her Name, Volume II 6308280/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-wonderful-world-of-julie-london- The Wonderful World of Julie London 7775694/songs Swing -

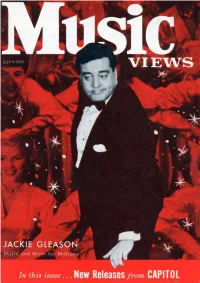

In This Issue... New Releases from CAPITOL the C O VER Music Views There Are Very Few People in July, 1955 Voi

In this issue... New Releases from CAPITOL THE C O VER Music Views There are very few people in July, 1955 Voi. XIII, No. 7 this country who have not come into contact with a TV set. There are even fewer who do not VIC ROWLAND .... Editor have access to a phonograph. Associate Editors: Merrilyn Hammond, Anyone who has a nodding ac Dorothy Lambert. quaintance with either of these appliances is sure to be fa miliar with either Jackie Gleason the comedian, Jackie Gleason GORDON R. FRASER . Publisher the musician, or both. This lat ter Jackie Gleason, the musi Published Monthly By cian, has recently succeeded in coming up with a brand new CAPITOL PUBLICATIONS, INC. sound in recorded music. It's Sunset and Vine, Hollywood 28, Calif. found in a new Capitol album, Printed in U.S.A. "Lonesome Echo." For the full story, see pages 3 to 5. Subscription $1.00 per year. A regular musical united nations is represented by lady and gentlemen pictured above. Left to right they are: Louis Serrano, music columnist for several South American magazines; Dean Martin, whose fame is international; Line Renaud, French chanteuse recently signed to Cap itol label; and Cauby Peixoto, Brazilian singer now on Columbia wax. 2 T ACKIE GLEASON has indeed provided mirth strument of lower pitch), four celli, a marim " and music to millions of people. Even in ba, four spanish-style guitars and a solo oboe. the few remaining areas where television has Gleason then selected sixteen standard tunes not as yet reached, such record albums as which he felt would lend themselves ideally "Music For Lovers Only" and other Gleason to the effect he had in mind. -

Introduction to Speedy West and Jimmy Bryant (Excerpts from Richie Unterberger, All Music Guide)

Introduction to Speedy West and Jimmy Bryant (Excerpts from Richie Unterberger, All Music Guide) Speedy West One of the greatest virtuosos that country music has ever produced, Speedy West bridged the western swing and rockabilly eras with eye-popping steel guitar. Besides contributing to literally thousands of country sessions, West cut many of his own instrumentals, as a solo act and with his guitarist partner Jimmy Bryant. Adept at boogie, blues, and Hawaiian ballads, West played with an infectious joy and daring improvisation that, at its most adventurous, could be downright experimental. It's doubtful whether anyone could collect all of Speedy's solos under one roof, but it was his sessions of the 1950s and early '60s -- especially those with Jimmy Bryant -- that found his genius at its most freewheeling and dazzling. Jimmy Bryant With steel guitar wizard Speedy West, guitarist Jimmy Bryant formed half of the hottest country guitar duo of the 1950s. With lightning speed and a jazz-fueled taste for improvisation and adventure, Bryant's boogies, polkas, and Western swing -- recorded with West and as a solo artist -- remain among the most exciting instrumental country recordings of all time. Bryant also waxed major contributions to the early recordings of singers like Tennessee Ernie Ford, Merrill Moore, Kay Starr, Billy May, and Ella Mae Morse, and has influenced country guitarists like Buck Owens, James Burton, and Albert Lee. While he enjoyed a career that spanned several decades, it was his sessions with Capitol Records in the early '50s that allowed him his fullest freedom to strut his stuff. -

The Center for Popular Music Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, Tn

THE CENTER FOR POPULAR MUSIC MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, MURFREESBORO, TN JESSE AUSTIN MORRIS COLLECTION 13-070 Creator: Morris, Jesse Austin (April 26, 1932-August 30, 2014) Type of Material: Manuscript materials, books, serials, performance documents, iconographic items, artifacts, sound recordings, correspondence, and reproductions of various materials Physical Description: 22 linear feet of manuscript material, including 8 linear feet of Wills Brothers manuscript materials 6 linear feet of photographs, including 1 linear foot of Wills Brothers photographs 3 boxes of smaller 4x6 photographs 21 linear feet of manuscript audio/visual materials Dates: 1930-2012, bulk 1940-1990 RESTRICTIONS: All materials in this collection are subject to standard national and international copyright laws. Center staff are able to assist with copyright questions for this material. Provenance and Acquisition Information: This collection was donated to the Center by Jesse Austin Morris of Colorado Springs, Colorado on May 23, 2014. Former Center for Popular Music Director Dale Cockrell and Archivist Lucinda Cockrell picked up the collection from the home of Mr. Morris and transported it to the Center. Arrangement: The original arrangement scheme for the collection was maintained during processing. The exception to this arrangement was the audio/visual materials, which in the absence of any original order, are organized by format. Collection is arranged in six series: 1. General files; 2. Wills Brothers; 3. General photographs; 4. Wills Brothers photographs; 5. Small print photographs; 6. Manuscript Audio/Visual Materials. “JESSE AUSTIN MORRIS COLLECTION” 13-070 Subject/Index Terms: Western Swing Wills, Bob Wills, Johnnie Lee Cain’s Ballroom Country Music Texas Music Oklahoma Music Jazz music Giffis, Ken Agency History/Biographical Sketch: Jesse Austin Morris was editor of The Western Swing Journal and its smaller predecessors for twenty years and a well-known knowledge base in western swing research. -

CLINE-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.391Mb)

Copyright by John F. Cline 2012 The Dissertation Committee for John F. Cline Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Steven Hoelscher Randolph Lewis Karl Hagstrom Miller Shirley Thompson Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking by John F. Cline, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my mother and father, Gary and Linda Cline. Without their generous hearts, tolerant ears, and (occasionally) open pocketbooks, I would have never made it this far, in any endeavor. A second, related dedication goes out to my siblings, Nicholas and Elizabeth. We all get the help we need when we need it most, don’t we? Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Mark Smith. Even though we don’t necessarily work on the same kinds of topics, I’ve always appreciated his patient advice. I’m sure he’d be loath to use the word “wisdom,” but his open mind combined with ample, sometimes non-academic experience provided reassurances when they were needed most. Following closely on Mark’s heels is Karl Miller. Although not technically my supervisor, his generosity with his time and his always valuable (if sometimes painful) feedback during the dissertation writing process was absolutely essential to the development of the project, especially while Mark was abroad on a Fulbright.