Typographic Reification: Instantiations from the Lucy Lloyd Archive And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pasts and Presence of Art in South Africa

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The pasts and presence of art in South Africa Technologies, ontologies and agents Edited by Chris Wingfield, John Giblin & Rachel King The pasts and presence of art in South Africa McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The pasts and presence of art in South Africa Technologies, ontologies and agents Edited by Chris Wingfield, John Giblin & Rachel King with contributions from Ceri Ashley, Alexander Antonites, Michael Chazan, Per Ditlef Fredriksen, Laura de Harde, M. Hayden, Rachel King, Nessa Leibhammer, Mark McGranaghan, Same Mdluli, David Morris, Catherine Namono, Martin Porr, Johan van Schalkwyk, Larissa Snow, Catherine Elliott Weinberg, Chris Wingfield & Justine Wintjes Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2020 © 2020 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The pasts and presence of art in South Africa is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-913344-01-6 On the cover: Chapungu – the Return to Great Zimbabwe, 2015, by Sethembile Msezane, Great Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. Photograph courtesy and copyright the artist. Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures -

Annotations of Loss and Abundance an Examination of the !Kun Children’S Material in the Bleek and Lloyd Collection (1879 – 1881) Marlene Winberg

Town Cape of University Annotations of loss and abundance An examination of the !kun children’s material in the Bleek and Lloyd Collection (1879 – 1881) Marlene Winberg The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University 2 Marlene Winberg WNBMAR001 A dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Art in Fine Art. Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2011 This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge the role of my two supervising professors: Pippa Skotnes from the Department of Fine Art and Carolyn Hamilton from the Department of Social Anthropology, as well as all the participants in the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative, who helped in the development of the ideas expressed in this thesis. I am grateful to José Manuel Samper-de Prada, post- doctoral research fellow at The Centre for Curating the Archive, for our insightful discussions. I acknowledge the financial support given to me by the Mellon Foundation, the National Research Foundation, Ford Foundation and UCT’s Jules Kramer Award. -

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER and PRECURSOR of ROCK ART CONSERVATION Today George William Stow Is Remembered Chiefly As

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER AND PRECURSOR OF ROCK ART CONSERVATION One thing is certain, if I am spared I shall use every effort to secure all the paintings in the state that I possibly can, that some record may be kept (imperfect as it must necessarily be .... ). I have never lost an opportunity during that time of rescuing from total obliteration the memory of their wonderful artistic labours, at the same time buoying myself up with the hope that by so doing a foundation might be laid to a work that might ultimately prove to be of considerable importance and value to the student of the earlier races of mankind. George William Stow to Lucy Lloyd, 4 June 1877 Today George William Stow is remembered chiefly as the discoverer of the rich coal deposits that were to lead to the establishment of the flourishing town of Vereeniging in the Vaal area (Mendelsohn 1991:11; 54-55). This achievement has never been questioned. However, his considerable contribution as ethnographer, recorder of rock art and as the precursor of rock art conservation in South Africa, has never been sufficiently acknowledged. In the chapter that follows these achievements are discussed against the backdrop of his geological activities in the Vereeniging area and elsewhere. Inevitably, this chapter also includes a critical assessment of the accusations of fraud levelled against him in recent years. Stow was a gifted historian and ethnographer and during his geological explorations he developed an abiding interest in the history of the indigenous peoples of South 13 Africa and their rich rock art legacy. -

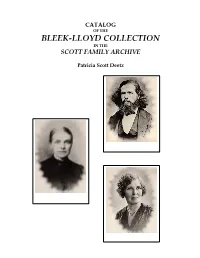

Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Scott Family Archive

CATALOG OF THE BLEEK-LLOYD COLLECTION IN THE SCOTT FAMILY ARCHIVE Patricia Scott Deetz © 2007 Patricia Scott Deetz Published in 2007 by Deetz Ventures, Inc. 291 Shoal Creek, Williamsburg, VA 23188 United States of America Cover Illustrations Wilhelm Bleek, 1868. Lawrence & Selkirk, 111 Caledon Street, Cape Town. Catalog Item #84. Lucy Lloyd, 1880s. Alexander Bassano, London. Original from the Scott Family Archive sent on loan to the South African Library Special Collection May 21, 1993. Dorothea Bleek, ca. 1929. Navana, 518 Oxford Street, Marble Arch, London W.1. Catalog Item #200. Copies made from the originals by Gerry Walters, Photographer, Rhodes University Library, Grahamstown, Cape 1972. For my Bleek-Lloyd and Bright-Scott-Roos Family, Past & Present & /A!kunta, //Kabbo, ≠Kasin, Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass’o and the other Informants who gave Voice and Identity to their /Xam Kin, making possible the remarkable Bleek-Lloyd Family Legacy of Bushman Research About the Author Patricia (Trish) Scott Deetz, a great-granddaughter of Wilhelm and Jemima Bleek, was born at La Rochelle, Newlands on February 27, 1942. Trish has some treasured memories of Dorothea (Doris) Bleek, her great-aunt. “Aunt D’s” study was always open for Trish to come in and play quietly while Aunt D was focused on her Bushman research. The portraits and photographs of //Kabbo, /Han≠kass’o, Dia!kwain and other Bushman informants, the images of rock paintings and the South African Archaeological Society ‘s logo were as familiar to her as the family portraits. Trish Deetz moved to Williamsburg from Charlottesville, Virginia in 2001 following the death of her husband James Fanto Deetz. -

Prison and Garden

PRISON AND GARDEN CAPE TOWN, NATURAL HISTORY AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATION HEDLEY TWIDLE PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JANUARY 2010 ii …their talk, their excessive talk about how they love South Africa has consistently been directed towards the land, that is, towards what is least likely to respond to love: mountains and deserts, birds and animals and flowers. J. M. Coetzee, Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech, (1987). iii iv v vi Contents Abstract ix Prologue xi Introduction 1 „This remarkable promontory…‟ Chapter 1 First Lives, First Words 21 Camões, Magical Realism and the Limits of Invention Chapter 2 Writing the Company 51 From Van Riebeeck‟s Daghregister to Sleigh‟s Eilande Chapter 3 Doubling the Cape 79 J. M. Coetzee and the Fictions of Place Chapter 4 „All like and yet unlike the old country’ 113 Kipling in Cape Town, 1891-1908 Chapter 5 Pine Dark Mountain Star 137 Natural Histories and the Loneliness of the Landscape Poet Chapter 6 „The Bushmen’s Letters’ 163 The Afterlives of the Bleek and Lloyd Collection Coda 195 Not yet, not there… Images 207 Acknowledgements 239 Bibliography 241 vii viii Abstract This work considers literary treatments of the colonial encounter at the Cape of Good Hope, adopting a local focus on the Peninsula itself to explore the relationship between specific archives – the records of the Dutch East India Company, travel and natural history writing, the Bleek and Lloyd Collection – and the contemporary fictions and poetries of writers like André Brink, Breyten Breytenbach, Jeremy Cronin, Antjie Krog, Dan Sleigh, Stephen Watson, Zoë Wicomb and, in particular, J. -

Between 1905 and Court Translator

N THE E LINES E ost of the indigenous languages learned their language, and recorded the vast body of the !Xam ku- Min South Africa owe their ex- kummi which they related to him over the next few years. Accord- W istence in written form to the ef- ing to JD Lewis-Williams, there is no adequate English translation of forts of the missionaries. With the the word kukummi, which encompasses ‘stories, news, talk, informa- T San people, however, it was differ- tion, history and what English-speakers call myths and folklore’. E ent. They had resisted religion, and The work was painstaking and laborious. Assisted by his sister-in- attempts at converting them to law, Lucy Lloyd, Bleek developed a phonetic script to accommodate B Christianity proved vain. It was also the clicks and other complex sounds of the language, and using this considered not a worthwhile project, script, Bleek and Lloyd recorded the kukummi in quarto notebooks. as they were also regarded as primi- Sentence by sentence, the text was entered in columns, with a trans- Cecily van Gend tive savages who should be exter- lation alongside. Often the stories were acted out, or pictures were minated to make way for the more drawn. The /Xam themselves also picked up English quite quickly. evolved races. The result of all this effort was The Bleek and Lloyd Collection, now The preservation of San culture, with its large and fascinating body housed in the University of Cape Town (UCT) library archives, com- of beliefs, history, folklore and customs in written form, is thanks to prising more than 12 000 numbered pages of text, word lists and the foresight, energy and dedication of a remarkable family: Wilhelm notes. -

From Central Asia to South Africa: in Search of Inspiration in Rock Art Studies

Werkwinkel 12(1), 2017, pp. 19-33 © Department of Dutch and South African Studies Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland DOI: 10.1515/werk-2017-0002 From Central Asia to South Africa: In Search of Inspiration in Rock Art Studies ANDRZEJ ROZWADOWSKI Adam Mickiewicz University Instytut Wschodni Wydział Historyczny Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza ul. Umultowska 89D 61-614 Poznań, Poland [email protected] Abstract: The paper describes the story of discovering South African rock art as an inspi- ration for research in completely different part of the globe, namely in Central Asia and Siberia. It refers to those aspect of African research which proved to importantly develop the understanding of rock art in Asia. Several aspects are addressed. First, it points to im- portance of rethinking of relationship between art, myth and ethnography, which in South Africa additionally resulted in reconsidering the ontology of rock images and the very idea of reading of rock art. From the latter viewpoint particularly inspiring appeared the idea of three-dimensionality of rock art ‘text’. The second issue of South African ‘origin,’ which notably inspired research all over the world, concerns a new theorizing of shaman- ism. The paper then discusses how and to what extent this new theory add to the research on the rock art in Siberia and Central Asia. Keywords: South Africa; Central Asia; rock art; interpretation When in 1992 I was beginning the research on rock art in Uzbekistan, not only Central Asia, but especially the phenomenon of rock art appeared to be a chal- lenge, which, as I soon realized, was diffi cult to face basing solely on traditional werkwinkel 12(1) 2017 20 Andrzej Rozwadowski archaeological education. -

Oratures, Oral Histories, Origins

Trim: 152mm × 228mm Top: 10.544mm Gutter: 16.871mm CUUK1609-01 cuuk1609 ISBN: 978 0 521 19928 5 August 19, 2011 15:43 part i * ORATURES, ORAL HISTORIES, ORIGINS South Africa’s indigenous orature is marked, on one hand, by its longevity, since it includes the oral culture of hunter-gatherer societies now known collectively as the San; on the other hand it is marked by its modernity, because oral performance in South Africa is continually being reinvented in contemporary, media-saturated environments. This range is fully represented in the research collected in Part i, as is the linguistic and generic variety of the oral cultures of the region. These chapters bear out Liz Gunner’s observation about recent research in African orature in The Cambridge History of African and Caribbean Literature: the older model of freestanding oral genres, manifested in the often very fine collections of single or relatively few genres of ‘oral literature’ from a particular African society such as those published by the pathbreaking Oxford Library of African Literature series in the late 1960sandthe1970s...hasbeen superseded by theories of orality that embrace a far more interactive and interdependent sense of cultural practices and ‘text’. (F. Abiola Irele and S. Gikandi, eds., Cambridge University Press, 2004,p.11) The research collected here demonstrates this trend, with each chapter paying particular attention to the ways in which prevailing social, cultural, economic and political conditions have shaped the genres under discussion. Whilst the chapters are organised on a linguistic basis in an effort to cover all the major 15 Trim: 152mm × 228mm Top: 10.544mm Gutter: 16.871mm CUUK1609-01 cuuk1609 ISBN: 978 0 521 19928 5 August 19, 2011 15:43 Oratures, oral histories, origins indigenous languages of the region, the authors have been concerned to move awayfromnotionsoforalcultureastiedtofictionsofstableethnicidentities,or to an understanding of oral genres as being passed down from one generation to the next in a state relatively untouched by historical circumstance. -

Courage of //Kabbo, The

Courage of //Kabbo, The Edition: 1st Edition Publication date: 2014 Author/Editors: ISBN: 9781919895468 Format: Soft Cover Number of Pages: 464 Retail price: R622.00 (incl. VAT, excl. delivery.) Website Link: juta.co.za/pdf/25243/ About this Publication: The year 2011 marked the centenary of the publication of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd’s publication, Specimens of Bushman Folklore, a unique and globally important record of the language and poetry of the now-extinct language of the |xam Bushmen. This edited volume celebrates this anniversary. It is named after ||Kabbo, a prisoner released from the Breakwater Convict Station in the 1870s, who remained in Cape Town far from home and family and sacrificed the freedom of his final years to teach Bleek and Lloyd his language and make his stories known by way of books. The stories in the Bleek and Lloyd archive are now all that remains of the world view of the |xam. Contents Include: Introduction Chapter 1: From landscape to literature: Specimens in images Chapter 2: The life of the Louis Fourie Archive of Khoisan Ethnologica Chapter 3: Louis Anthing (1829-1902) Chapter 4: The methodological basis of Wilhelm Bleek’s Reynard the Fox in South Africa (1864): a precursor to the Specimens Chapter 5: The story of ││Kabbo and Reynard the Fox: notes on cultural and textual history Chapter 6: The foundation of African studies: Wilhelm Bleek’s African linguistics and the first ethnographers of southern Africa Chapter 7: Gathering wisdom: reassembling Wilhelm Bleek’s library Chapter 8: The Bleek and -

Story Experience in a Virtual San Storytelling Environment: a Cultural Heritage Application for Children and Young Adults

STORY EXPERIENCE IN A VIRTUAL SAN STORYTELLING ENVIRONMENT: A CULTURAL HERITAGE APPLICATION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG ADULTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE, FACULTY OF SCIENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE By Ilda Ladeira 2005 Supervised by Edwin H. Blake Copyright 2005 by Ilda Ladeira A lot of our culture is lost in our lives – the old stories that were told by mothers and fathers who would go into the bush and then return to tell the others what they had seen…. We have no stories to tell our children. We have nothing to pass on. We will have to find the strength to make a place for ourselves in this world. Otherwise there will soon be no more of us. We will all be gone. And so will our memories. Only our paintings will remain behind to remind you of us. Quote from Mario Mahongo, a !Xu Bushman National Geographic (Godwin, 2001) Abstract This dissertation explores virtual storytelling for conveying cultural stories effectively. We set out to investigate: (1) the strengths and/or weaknesses of VR as a storytelling medium; (2) the use of a culturally familiar introductory VE to preface a VE presenting traditional storytelling; (3) the relationship between presence and story experience. We conducted two studies to pursue these aims. Our aims were stated in terms of effective story experience, in the realm of cultural heritage. This was conceptualised as a story experience where story comprehension, interest in the story’s cultural context and story enjoyment were achieved, and where boredom and confusion in the story were low. -

Of a Rock Art Painting

Exposé or misconstrual? Exposé or misconstrual? Unresolved issues of authorship and the authenticity of GW Stow’s ‘forgery’ of a rock art painting MARGUERITE PRINS Abstract. George William Stow (1822-1882) is today considered to have been one of the founding fathers of rock art research and conservation in Southern Africa. He arrived from England in 1843 and settled on the frontier of the Eastern Cape where he gradually started specializing in geological exploration, the ethnological history of the early peoples of the subcontinent and the rock art of the region. By the 1870s he was responsible for the discovery of the coalfields in the Vaal Tri- angle of South Africa. In recent years Stow’s legacy has been the subject of academic suspicion. Some rock art experts claim that he made himself guilty of ‘forgery’. In the article the authors argues in favour of restoring the status of Stow by pointing to the fact that two mutually exclusive interpretational approaches of rock art, than it is about an alleged forgery, are at the heart of the attempts at discrediting his work. In the process, irreparable and undeserving harm has been done to the name of George William Stow and his contribution to rock art research and conservation in South Africa. Key words. GW Stow, rock art, shamanistic approach, geology, archaeology, herit- age conservation. Introduction For the researcher engaged in a study of the rock engravings of Redan near Vereeniging, it is usually inevitable to come across the name of George William Stow (1822-1882). Stow discovered the rich coal fields in the Vaal area that would lead to the formation of a vast coal empire and the establishment of the industrial city of Vereeniging.2 Stow also laid the foundation for rock art research and conservation in South Africa. -

Alternation Article Template

Meat as well as Books Shane Moran Review Article The Courage of ||kabbo. Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Publication of Specimens of Bushman Folklore Edited by Janette Deacon & Pippa Skotnes Cape Town. UCT Press, 2014, ix + 456pp. ISBN-13: 978-1919895468 It was typical of the plight of the Bleekmen, this conclusion to their trek. (Philip K. Dick, Martian Time-Slip, 24) The Courage of ||kabbo. Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Publication of Specimens of Bushman Folklore originated in the conference organised to celebrate W.H.I. Bleek and Lucy Lloyd’s Specimens of Bushman Folklore (1911). This was the fourth in a series of meetings dating from 1991 organised to celebrate the work of Bleek, his sister-in-law Lloyd, and Bleek’s daughter Dorothea. The first meeting resulted in Voices from the Past (1996), edited by Janette Deacon and Thomas Dowsen. A second conference was held in Germany in 1994. Most significant was the 1996 Miscast exhibition that sparked the ongoing participation of those identifying themselves as San and Khoe descendants and appeared as Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushmen (Skotnes 1996). The present volume embraces the textual apparatus of Pippa Skotnes’ lavishly illustrated Claim to the country: the archive of Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek (2007) utilising graphic design to provide exquisite scanned images of various artifacts. Although primarily of interest to historians of linguistics and anthropologists, the Bleek and Lloyd archive has inspired visual artists, museum curators, sculptors, and poets. The work of the African philologists has become part of the décor of modernity.