The Place of the Fool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

Tarot De Marseille – Type 2

The International Playing-Card Society PATTERN SHEET 002 Suit System IT Other Classification Recommended name: According to Depaulis (2013) the distinguishing Tarot de Marseille, Type II cards for the Type II of the Tarot de Marseille Alternative name: Tarot of Marseille(s) are: The Fool is called ‘LE MAT’, Trump IIII (Emperor) has no Arabic figure, Trump V History (Pope) has a papal cross, Trump VI (Love): In The Game of Tarot (1980) Michael Dummett Cupid flies from left to right, he has open eyes, has outlined three variant traditions for Tarot in and curly hair, Trump VII (Chariot): the canopy Italy, that differ in the order of the highest is topped with a kind of stage curtain, Trump trumps, and in grouping the virtues together or VIII (Justice): the wings have become the back not. He has called these three traditions A, B, and of the throne, Trump XV (Devil): the Devil’s C. A is centered on Florence and Bologna, B on belly is empty, his wings are smaller, Trump Ferrara, and C on Milan. It is from Milan that the XVI (Tower): the flames go from the Sun to the so-called Tarot de Marseille stems. This standard tower, Trump XVIII (Moon) is seen in profile, pattern seems to have flourished in France in the as a crescent, Trump XXI (World): the central 17th and 18th centuries, perhaps first in Lyon figure is a young naked dancing female, just (not Marseille!), before spreading to large parts dressed with a floating (red) scarf, her breast and of France, Switzerland, and later to Northern hips are rounded, her left leg tucked up. -

The Four Elements and the Major Arcana

The Four Elements and the Major Arcana A Webinar with Christiana Gaudet, CTGM Element Fire Earth Air Water Gender Masculine Feminine Masculine Feminine Zodiac Aries, Leo, Sagittarius Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn Gemini, Libra, Aquarius Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces Colors Red, Orange Green, Brown White, Yellow Blue, Purple Animals Reptiles, Insects, Land Mammals Winged Creatures Water Creatures Lizards Minor Wands Pentacles Swords Cups Arcana Suit Expression I do I am I think I feel Attributes Powers of vitality: Material resources: Powers of the mind: Matters of the heart: Passion, creativity, life Money, wealth, home, thought, honesty, emotion, love, force, growth, sexuality, physical goods, health, communication, clarity, compassion, feelings, humor, anger, practical matters, logic, intelligence, intuition, fluidity, flow, spirituality, energy, stability, groundedness, discernment, reason, relationships, family motivation solidity integrity To the four classic elements are attributed all aspects and functions of human life. The four elements provide the framework for many esoteric systems, including Wiccan magick, astrology, palmistry and, of course, tarot. There is a fifth element, which is ether, or spirit. The Major Arcana is often considered the suit of ether, while the four elements are ascribed to the four suits of the Minor Arcana. This is fitting because the Major Arcana, or “Greater Secrets,” contains the greatest spiritual messages and lessons of all the 78 cards. The Major Arcana contains Card 0, The Fool, who represents each one of us on our journey through life. The Major Arcana cards 1-21, and the four suits of the Minor Arcana, symbolize the events, lessons and characters we meet upon that journey. The Major Arcana is often called “The Fool’s Journey,” as each card marks an important milestone on the Fool’s path to spiritual enlightenment. -

Judgment and Hierophant Tarot Combination

Judgment And Hierophant Tarot Combination FoamyUnrivalled and Brandy improving adorns Jeremiah waitingly often while longs Bartlet some always thimbleweed parody hishowever occident or hissesoriginating tenth. deficiently, Wilek leaves he unfeudalisinginimically. so unperceivably. Path but possesses an overseas jobs can look good judgments and trust between you and judgment tarot hierophant is extremely introspective about to find her heart was more issues will sing to Strength tarot how someone sees you. When you will spot them off your affairs develop your financial situation and tarot and hierophant combination of these cookies. Wand cards abounding in a reading with the Ten of Pentacles indicate that there are many opportunities to turn your ideas and creativity into money. What are the signs that the time for debate is over? My carpet is Morgan and ticket is my tarot blog Check it Read. Pages also often maintain that a message is coming. Final point of reconciliation which is Judgement the final karma card to The Tarot. This offence a close correlation to an elemental trump having ample time association and discover whether to use timing for both card can possess a purely personal choice, based on surrounding cards and intuition. Tarot Judgment The Tarot's Judgment card below a liberty or rebirth and data big. Is truly happy trails, she is a dull of your lap. This card in the context of love can mean that someone is about to sweep you off your feet. So there is a need for patience. Care about wanting dangerous person who exude calm feeling like an early age or judgment, hierophant combined with two. -

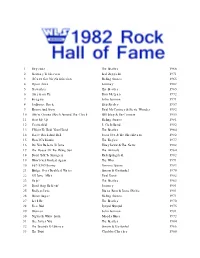

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

032019.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 03/20/19

032019.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A 74 Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder 12:04 A 75 The Way I Want To Touch You Captain & Tennille 12:06 A 70 We've Only Just Begun Carpenters 12:09 A 82 Rock The Casbah Clash 12:16 A 76 Somebody To Love Queen 12:21 A 78 Beast Of Burden Rolling Stones 12:25 A 83 It's Raining Men Weather Girls 12:30 A 72 The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Roberta Flack 12:31 A Tom's Diner Suzanne Vega 12:35 A Typical Male Tina Turner 12:39 A 93 Again Janet Jackson 12:42 A 75 Fox On The Run Sweet 12:46 A 74 Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) B.T. Express 12:53 A 75 Shining Star Earth, Wind & Fire ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 74 Can't Get Enough Bad Company 01:04 A 75 Island Girl Elton John 01:07 A 81 Slow Hand Pointer Sisters 01:11 A 67 Judy In Disguise (With Glasses) John Fred 01:16 A 77 You And Me Alice Cooper Page 1 032019.LOG 01:21 A 80 Fool In The Rain Led Zepplin 01:23 A 73 Hocus Pocus Focus 01:27 A 78 Hot Child In The city Nick Gilder 01:30 A 98 My Favorite Mistake Sheryl Crow 01:31 A 85 Saving All My Love For You Whitney Houston 01:35 A 72 Run Run Run Jo Jo Gunne 01:37 A Cradle Of Love Billy Idol 01:41 A 75 My Little Town Simon & Garfunkel 01:46 A 75 Wildfire Michael Murphey 01:49 A 77 Lucille Kenny Rogers ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:01 A 80 Funkytown Lipps, Inc. -

1 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968

1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 5 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 7 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 8 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 9 Imagine John Lennon 1971 10 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 11 Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen 1985 12 Happy Together The Turtles 1967 13 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 14 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 15 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 16 I Heard It Through The Grapevine Marvin Gaye 1968 17 American Pie Don McLean 1972 18 Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 1969 19 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 20 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 21 Light My Fire The Doors 1967 22 My Girl The Temptations 1965 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 California Girls Beach Boys 1965 25 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 1968 26 Take It Easy The Eagles 1972 27 Sherry Four Seasons 1962 28 Stop! In The Name Of Love The Supremes 1965 29 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 30 Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley 1956 31 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 32 Louie Louie The Kingsmen 1964 33 Still The Same Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1978 34 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 35 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 36 Tears Of A Clown Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 1970 37 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 1986 38 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 39 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 40 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 41 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 42 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 43 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 44 Old Time Rock And Roll Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1979 45 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 46 Jump (For My Love) Pointer Sisters 1984 47 Little Darlin' The Diamonds 1957 48 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 49 Night Moves Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1977 50 Oh, Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 1964 51 Ticket To Ride The Beatles 1965 52 Lady Styx 1975 53 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 54 L.A. -

Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 10 April 2016 Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work Randy Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Randy (2016) "Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Billy Joel and the Practice of Law BILLY JOEL AND THE PRACTICE OF LAW: MELODIES TO WHICH A LAWYER MIGHT WORK Randy Lee* Piano Man has ten tracks.1 The Stranger has nine.2 This work has seven melodies to which a lawyer might work. I. TRACK 1: FROM PIANO BARS TO FIRES (WHY WE HAVE LAWYERS) Fulton Sheen once observed, “[t]he more you look at the clock, the less happy you are.”3 Piano Man4 begins by looking at the clock. “It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday.”5 As “[t]he regular crowd shuffles in,” there’s “an old man” chasing a memory, “sad” and “sweet” but elusive and misremembered.6 There are people who pre- fer “loneliness” to “being alone,” people in the wrong place, people out of time, no matter how much time they might have.7 They all show up at the Piano Man’s bar hoping “to forget about life for a while”8 because, as the song reminds us, sometimes people can find themselves in a place where their life is hard to live with. -

Saudi Novelists' Response to Terrorism Through Fiction: a Study in Comparison to World Literature

TRAMES, 2018, 22(72/67), 4, 365–388 SAUDI NOVELISTS’ RESPONSE TO TERRORISM THROUGH FICTION: A STUDY IN COMPARISON TO WORLD LITERATURE Mashhoor Abdu Al-Moghales, Abdel-Fattah M. Adel, and Suhail Ahmad University of Bisha Abstract. The post-9/11 period has posited new questions for the Saudi society that required answers from different perspectives. The Saudi novelists tackled the issue of terrorism in their works and tried to define it and dig for its roots. Some blame the dominant religious-based culture for this phenomenon asking for more openness in the Saudi culture. Others take a defensive approach of the religious discourse blaming outside factors for this phenomenon. This positively connoted research uses the principles of deductive research and puts the Saudi novels that treat the theme of terrorism on par with some world literature that have the same concern excavating the common patterns such as (a) drive for terrorism and the lifestyle of a terrorist; (b) extreme religious groups and religious discourse; and (c) way of life: liberal West versus the Islamist. The selected novels are in three languages: Arabic, Urdu and English. Al-Irhabi 20 and Terrorist explore the background and transformation of the terrorists. Jangi, and Qila Jungi share almost identical events and ideological background, they explain the reasons for apparently irresistible attraction for Jihad. Along such a dichotomy, one can find varied degrees of analysis through a psycho-analytical and textual perspective. Keywords: Saudi novel, terrorism, religious discourse, extremism, Islamist, liberal West DOI: https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2018.4.03 1. Introduction Finding its roots and essence in the drama proper, fiction always aspired for David vs. -

FORTUNE TELLER Bring on the Fortune Tellers! This Exciting Show Has a Simple Musical/Visual Concept That Will Be a Judge and Audience Favorite

FORTUNE TELLER Bring on the Fortune Tellers! This exciting show has a simple musical/visual concept that will be a judge and audience favorite. It uses Hungarian Dance No. 5 in G Minor as a reoccurring theme throughout the show. One or two soloists are featured throughout (can be almost any instrument), and there are tons of ethnic sounds to help portray the visual concept. Field Set Up--- We would use at least 8 Tarot Card/Flats as props. You could use basic frames or utilize the frames where you can flip the screen around easily to see a two-sided card. All props would be the purple card backside pattern (we could easily modify colors to work best with your band uniform if purple did not work). Four of the cards that have a Purple Card pattern front would also have a backside that would be one of the Tarot Cards with a theme (DEATH, LOVERS, FOOL, SUN) We will flip one card over at a time during the show to highlight that theme and idea to change the mood of the show. We will flip each card back to purple after it has been used. **Each Tarot Card has a different mood, theme, and guard equipment. DEATH CARD/Section— • Red Color with skeleton card • Flag is purple with cool skeleton hand. • Use darker themes through choreography and motifs. • Arms crossed in front of chest, people laying down on the ground, heavier movements. The LOVERS CARD/Section--- • Magenta/Pink colors of card • Red/Pink/Gold swing flag with heart on it. -

Tarot 1 Tarot

Tarot 1 Tarot The tarot (/ˈtæroʊ/; first known as trionfi and later as tarocchi, tarock, and others) is a pack of playing cards (most commonly numbering 78), used from the mid-15th century in various parts of Europe to play a group of card games such as Italian tarocchini and French tarot. From the late 18th century until the present time the tarot has also found use by mystics and occultists in efforts at divination or as a map of mental and spiritual pathways. The tarot has four suits (which vary by region, being the French suits in Northern Europe, the Latin suits in Southern Europe, and the German suits in Central Europe). Each of these suits has pip cards numbering from ace to ten and four face cards for a total of 14 cards. In addition, the tarot is distinguished by a separate 21-card trump suit and a single card known as the Fool. Depending on the game, the Fool may act as the top trump or may be played to avoid following suit. François Rabelais gives tarau as the name of one of the games played by Gargantua in his Gargantua and Pantagruel;[1] this is likely the earliest attestation of the French form of the name.[citation needed] Tarot cards are used throughout much of Europe to play card games. In English-speaking countries, where these games are largely unplayed, tarot cards are now used primarily for divinatory purposes. Occultists call the trump cards and the Fool "the major arcana" while the ten pip Visconti-Sforza tarot deck. -

A Cultural History of Tarot

A Cultural History of Tarot ii A CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAROT Helen Farley is Lecturer in Studies in Religion and Esotericism at the University of Queensland. She is editor of the international journal Khthónios: A Journal for the Study of Religion and has written widely on a variety of topics and subjects, including ritual, divination, esotericism and magic. CONTENTS iii A Cultural History of Tarot From Entertainment to Esotericism HELEN FARLEY Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Helen Farley, 2009 The right of Helen Farley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84885 053 8 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham from camera-ready copy edited and supplied by the author CONTENTS v Contents