11 the Development of Attitudes to Foreign Languages As Shown in the English Novel Philip Shaw Stockholm University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men, Women, and Property in Trollope's Novels Janette Rutterford

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 33 Article 9 Issue 2 December 2006 2006 Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Janette Rutterford Josephine Maltby Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Rutterford, Janette and Maltby, Josephine (2006) "Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rutterford and Maltby: Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 33, No. 2 December 2006 pp. 169-199 Janette Rutterford OPEN UNIVERSITY INTERFACES and Josephine Maltby UNIVERSITY OF YORK FRANK MUST MARRY MONEY: MEN, WOMEN, AND PROPERTY IN TROLLOPE’S NOVELS Abstract: There is a continuing debate about the extent to which women in the 19th century were involved in economic life. The paper uses a reading of a number of novels by the English author Anthony Trollope to explore the impact of primogeniture, entail, and the mar- riage settlement on the relationship between men and women and the extent to which women were involved in the ownership, transmission, and management of property in England in the mid-19th century. INTRODUCTION A recent Accounting Historians Journal article by Kirkham and Loft [2001] highlighted the relevance for accounting history of Amanda Vickery’s study “The Gentleman’s Daughter.” Vickery [1993, pp. -

Barchester Towers 1St Edition Free Download

FREE BARCHESTER TOWERS 1ST EDITION PDF Anthony Trollope | 9780140432039 | | | | | 1st Edition Anthony Trollope Antiquarian & Collectible Books in English for sale | eBay Published by Everyman's Library London Seller Rating:. About this Item: Everyman's Library London, Condition: Near Fine. Dust Jacket Included. These superb and elegantly designed books were relaunched in London into great praise. Byatt said They are so beautifully produced. They are a form of civilization. John Updike wrote, They are the edition of record. They are, unsurprisingly, being collected, and the first printings especially. This is one of them. It has a unique introduction by Victoria Glendinning. There is a fascinating chronology, a bibliography, and an elegant setting, as befits this Victorian masterwork. A silk marker is bound in and the dark red cloth binding has a black panel on the spine with the title in gilt. This copy has a mylar sleeved jacket, which is unclipped. A slightly used look to the jacket, which has a slightly darkened spine with a very slight crease to the jacket. Language: eng Language: eng 0. Seller Inventory Barchester Towers 1st edition More information about this seller Contact this seller Condition: Very Good. First edition thus. Color illustrations by Fritz Kredel. Includes Sandglass. Very good with foxing to the foredges and Barchester Towers 1st edition to the hinges Barchester Towers 1st edition binder's glue, tiny puncture to spine in near fine slipcase. Seller Inventory From: Vagabond Books, A. First Edition. Signed by Author s. Published by Thomas Nelson, London About this Item: Thomas Barchester Towers 1st edition, London, Note: 1st Edition Edition details: first thus. -

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N. John Hall THE NEW ZEALANDER (editor) SALMAGUNDI: BYRON, ALLEGRA, AND THE TROLLOPE FAMILY TROLLOPE AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Edited by N. John Hall Selection and editorial matter © N. John Hall 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-26298-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-04608-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04606-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04606-5 Typeset in 10/12pt Press Roman by STYLESET LIMITED ·Salisbury· Wiltshire Contents Introduction vii HENRY JAMES Anthony Trollope 21 FREDERIC HARRISON Anthony Trollope 21 w. P. KER Anthony Trollope 26 MICHAEL SADLEIR The Books 34 Classification of Trollope's Fiction 42 PAUL ELMER MORE My Debt to Trollope 46 DAVID CECIL Anthony Trollope 58 CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER Trollope 66 A. 0. J. COCKSHUT Human Nature 75 FRANK O'CONNOR Trollope the Realist 83 BRADFORD A. BOOTH The Chaos of Criticism 95 GERALD WARNER BRACE The World of Anthony Trollope 99 GORDON N. RAY Trollope at Full Length 110 J. HILLIS MILLER Self and Community 128 RUTH apROBERTS The Shaping Principle 138 JAMES GINDIN Trollope 152 DAVID SKILTON Trollopian Realism 160 C. P. SNOW Trollope's Art 170 JOHN HALPERIN Fiction that is True: Trollope and Politics 179 JAMES R. KINCAID Trollope's Narrator 196 JULIET McMASTER The Author in his Novel 210 Notes on the Authors 223 Selected Bibliography 226 Index 243 Introduction The criticism of Trollope's works brought together in this collection has been drawn from books and articles published since his death. -

![S4xc1 [DOWNLOAD] Ralph the Heir Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8200/s4xc1-download-ralph-the-heir-online-1608200.webp)

S4xc1 [DOWNLOAD] Ralph the Heir Online

s4xC1 [DOWNLOAD] Ralph the Heir Online [s4xC1.ebook] Ralph the Heir Pdf Free Anthony Trollope DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Trollope Anthony 2015-11-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.69 x 1.01 x 7.44l, 1.74 #File Name: 1519469578446 pagesRalph the Heir | File size: 19.Mb Anthony Trollope : Ralph the Heir before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Ralph the Heir: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Decent late 19th century inheritance novelBy Alyssa MarieBasically, this story explores the concepts behind inheritance, property, illegitimacy, and marriage, among others. Some concepts that I didn’t at all expect to be thrown in were dirty election campaigns, which I thought was a lot of fun to read about — it’s vastly different from my own experience as an American citizen, although I’m sure times have changed in England and it’s also vastly different over there today.While I enjoyed reading the story to get a feel for the arguments Trollope makes about inheritance and such, it was a very long novel. It dragged a bit in in the middle, but was overall fairly interesting. It’s certainly not a fun, light read, however. The characters are fashioned more like character studies rather than original fictional people who are super developed and feel like friends and acquaintances; rather, they are carefully crafted to fit into Trollope’s world of proving points about morals, values, and class.If you’re studying the late 19th century and want to get a better feel for the era and the social problems they experienced then (as perceived by Trollope) — I think this works great as a companion work. -

Download Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868

Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868, , . DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1boZHoo Ayala's Angel (Sparklesoup Classics) , Anthony Trollope, Dec 5, 2004, , . Sparklesoup brings you Trollope's classic. This version is printable so you can mark up your copy and link to interesting facts and sites.. Orley Farm , Anthony Trollope, 1935, Fiction, 831 pages. This story deals with the imperfect workings of the legal system in the trial and acquittal of Lady Mason. Trollope wrote in his Autobiography that his friends considered this .... The Toilers of the Sea , Victor Hugo, 2000, Fiction, 511 pages. On the picturesque island of Guernsey in the English Channel, Gilliatt, a reclusive fisherman and dreamer, falls in love with the beautiful Deruchette and sets out to salvage .... The Way We Live Now Easyread Super Large 18pt Edition, Anthony Trollope, Dec 11, 2008, Family & Relationships, 460 pages. The Duke's Children , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The sixth and final novel in Trollope's Palliser series, this 1879 work begins after the unexpected death of Plantagenet Palliser's beloved wife, Lady Glencora. Though wracked .... He Knew He Was Right , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . Written in 1869 with a clear awareness of the time's tension over women's rights, He Knew He Was Right is primarily a story about Louis Trevelyan, a young, wealthy, educated .... Framley Parsonage , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The fourth work of Trollope's Chronicles of Barsetshire series, this novel primarily follows the young curate Mark Robarts, newly arrived in Framley thanks to the living .... Ralph the Heir , Anthony Trollope, 1871, Fiction, 434 pages. -

Bullough Collection.Doc

Special Collections and Archives: Bullough Collection This collection comprises around 550 nineteenth-century novels, and was assembled specifically for the purpose of studying dialogue. It was donated to the National Centre for English Cultural Tradition at the University of Sheffield in July 1981 by Professor Geoffrey Bullough, Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield from 1933 to 1946, and transferred to the University Library’s Special Collections department in 2007. Abbott, Edwin A. (Edwin Abbott), 1838-1926 Silanus the Christian ; by Edwin A. Abbott. - London : Adam and Charles Black, 1906. [x4648933] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 1 200350616 Abbott, Jacob Rollo at work and Rollo at play ; by Jacob Abbott. - London : Dent, [19--?]. - (Everyman's library). [z1799732] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 2 200350617 Alain-Fournier, 1886-1914 The wanderer = (le grand meaulnes) ; (by) Alain-Fournier ; translated from the French by Françoise Delisle. - London : Constable, [19--]. [M0010805SH] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 3 200350618 Alcott, Louisa M. (Louisa May), 1832-1880 Little women, and, Little women wedded = or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy ; by Louisa M. Alcott. - London : Sampson Low, Marston, [19--?]. [M0010807SH] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 4 200350619 Allen, Grant, 1848-1899 The woman who did ; by Grant Allen. - London : John Lane, 1895. [x5565072] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 5 200350620 Ashford, Daisy, 1881-1972 The young visiters or, Mr. Salteenas plan ; by Daisy Ashford. - London : Chatto & Windus, 1919. [x360339x] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 6 200350621 Atherton, Gertrude American wives and English husbands ; (by) Gertrude Atherton. - London : Collins, [190-?]. [x7458073] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 7 200350622 Atherton, Gertrude The Californians ; by Gertrude Atherton. - Leipzig : Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1899. [M0010817SH] BULLOUGH COLLECTION 8 200350623 1 Bullough Collection Austen, Jane, 1775-1817 Emma : a novel ; by Jane Austen. -

Moguntina, 1515. T Y I 0 71

TRITHEIM (JOHANN). --- Opera historica. Ed. Fresher. Frankfurt 1601. Pt. I et II. Unveranderter- Nachdruck. Frankfurt/Main, 1966. .9(101-021) Tri. --- J.T. ... tomus I. Annalium Hirsaugiensium ... Tom. 1, pars 1. S. Galli. E.B.F .2711(4348) Tri. 1, 1. Complectens historiam Franciae et Germaniae ... 1690. --- Compediu sive breviariu primi voluminis annalium, sive historiarum de origine regum et gentis Francorum ... J. Tritemij. Moguntina, 1515. T y I 0 71 --- De reprobis atq; maleficis quaestiones iii. See JACQUIER (N.). Flagellum haereticorum fascinariorum ... --- Ex libro J.T. octo quaestionum libellus. De reprobis atque maleficis quaestio quinta. See AGRIPPA (H.C.). H.C.A. ... de occulta philosophia lib. iii ... --- De scriptorib t eccl t iasticis ... Johannis de Trittehem ... _ De scriptoribus ecclesiasticis collectanea: Additis nonulloru ex recetiorib t vitis & noibus ... TFj 23-7 Pu r r^ ► i si Is 12 , 7 --- Another ed. Liber de ecclesiasticis scriptoribus. See FABRICIUS (J.A.). Bibliotheca ecclesiastica. Polygraphiae libri sex ... Accessit clavis Polygraphiae liber unus ... Additae sunt ... locorum explicationes ... per ... A. a Glauburg ... Coloniae, 1571. De .9-59. --- J.T. Libri Polygraphiae VI. Quibus praeter clavem et observationes A. a Glauburg. Accessit noviter eiusdem authoris Libellus de septem secundeis seu intelligentiis orbes post Deum moventibus, cum aliquot epistolis ex opere epistolarum utilissimis ... Argentorati, 1613. Ha.9.32. [Continued overleaf.] TRITHEIM (JOHANN) [continued]. --- Steganographia: hoc est, ars per occultam scripturam animi sui, voluntatem absentibus aperiendi certa ... Praefixa, est huic opert sua clavis ... ab ipso authore concinnata ... 2 pts. (in 1). Francofuxti, 1606. 0.20.86. --- Das wonder Buchlein. Wie die weldt von anfang geregiert and erhalten ist .. -

Trollope Cata 213.Indd 1 02/04/2015 14:17:25 TROLLOPE FAMILY

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXIII SPRING 2015 ANTHONY TROLLOPE 1815-1882 A Bicentenary Catalogue Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Ed Nassau Lake & Carol Murphy This catalogue celebrates 200 years since the birth of Anthony Trollope on April 24th 1815. Included, also, are books by his mother, Frances & his brother Thomas Adolphus. We would like to thank Geordie Greig for encouraging us to issue this catalogue in time for Trollope’s birthday. All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (current rate 20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: The Romantics: A-Z; The Romantic Background; The Museum: a Jarndyce Miscellany; Books from the Library of Geoffrey & Kathleen Tillotson; The Shop Catalogue; Dickens & His Circle; The Library of a Dickensian; Books & Pamphlets 1476-1838. Street Literature III: Songsters, Reference Sources, Lottery Tickets & ‘Puffs’; JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: Conduct & Education; Novels; Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Dickens Catalogue. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. -

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope By Henry S. Drinker British novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) wrote, in addition to 47 novels, an autobiogra- phy, a book on Thackeray, five travel books, and 42 short stories. Henry S. Drinker (1880–1965) was a partner in the law firm of Drinker Biddle and was also a musicologist. The essay that follows was an address delivered to members of the Grolier Club in New York City on Nov. 15, 1949. It is presented as it was published by the Grolier Club in 1950, in a book en- titled Two Addresses Delivered to Members of the Grolier Club; the other essay that appears in the book is “Trollope’s America” by Willard Thorp. Only 750 copies of the book were printed. hen I received the delightful invitation to speak Trollope was—perhaps I should say he became—an on Trollope—one of my chief enthusiasms—it extraordinarily careful observer of what was passing was immediately clear to me that my subject around him, and his genius lay in his ability to re-create, must be his lawyers; first, because, as a lawyer, I should with convincing vividness, the types of people whom he Wthus be able to make a more valuable contribution to the observed wherever he chanced to be. He did not create growing store of comment on his writings, and, second, his characters with any desire to point a moral, nor did he because I believe that Trollope’s ideas about and attitude use them as a medium for expressing his own ideas or toward lawyers have not been understood or appreciated epigrams. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

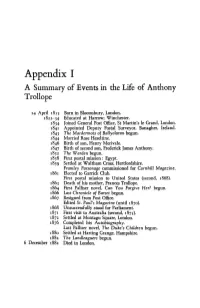

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

From Clerks to Corpora Essays on the English Language Yesterday and Today

From Clerks to Corpora essays on the english language yesterday and today Editors: Philip Shaw Britt Erman Gunnel Melchers Peter Sundkvist From Clerks to Corpora: essays on the English language yesterday and today Philip Shaw, Britt Erman, Gunnel Melchers & Peter Sundkvist Essays in honour of Nils-Lennart Johannesson Stockholm English Studies 2 Editorial Board Claudia Egerer, Associate Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Stefan Helgesson, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Nils-Lennart Johannesson, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Maria Kuteeva, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Nils-Lennart Johannesson is normally a member of the Editorial Board for the Stockholm English Studies book series. He has however not been involved in the editorial process of this publication. Published by Stockholm University Press Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm Sweden www.stockholmuniversitypress.se Text © The Authors License CC-BY Supporting Agencies (funding): Department of English, Stockholm University First published 2015 Cover Illustration: MS Wellcome 537, f. 15r. Reproduced by permission of © Wellcome Library, London. Cover designed by Karl Edqvist, SUP Stockholm English Studies (Online) ISSN: 2002-0163 ISBN (Hardback): 978-91-7635-004-1 ISBN (PDF): 978-91-7635-005-8 ISBN (EPUB): 978-91-7635-006-5 ISBN (Kindle): 978-91-7635-007-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16993/sup.bab Erratum: 2 weeks after publication the following text was added to the title page of chapter 20 (p367): ’Based on an unfinished manuscript, posthumously edited by Cecilia Ovesdotter Alm.’ This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.