A Conversation with Catholic Bishops and Scholars Regarding the Theology of Work and the Dignity of Workers: a Panel Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theology of Work and the Dignity of Workers"

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 50 Number 1 Volume 50, 2011, Numbers 1&2 Article 2 Foreword to "The Theology of Work and the Dignity of Workers" David L. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFERENCE THE THEOLOGY OF WORK AND THE DIGNITY OF WORKERS FOREWORD DAVID L. GREGORYt On All Souls' Day, November 2, 1987, Cesar Chavez, founder of the National Farm Workers Association-later, the United Farm Workers ("UFW")-discussed the evils of pesticides with a standing-room-only audience at St. John's University. Despite sharp disagreements between their union and the UFW in that era, even officials from the International Brotherhood of Teamsters joined the crowd in applause and lauded Chavez for his moving words. Afterward, Cesar told me that his brief sojourn at St. John's had been one of the most gratifying, engaging days he had enjoyed in years. A quarter-century later, on March 18 and 19 of 2011, St. John's was the site of another landmark event: the Conference- and subject of this Symposium Volume of the Journal of Catholic Legal Studies-"The Theology of Work and the Dignity of Workers."' Clergy, scholars, union representatives, and attorneys from diverse-even divergent-perspectives gathered for dialogue and exchange regarding the singular adversities facing workers around the world today. -

February 22, 2012 Cvol

THE CATHOLIC February 22, 2012 CVol. 50, No. 1 ommentatorSERVING THE DIOCESE OF BATON ROUGE SINCE 1963 thecatholiccommentator.org Revised contraceptive mandate prompts reaction from Catholic groups By Carol Zimmermann Other critics also said the change was a mat- Catholic News Service ter of semantics and still failed to address the A Letter to Louisiana Catholics: conscience rights of faith groups and the issue WASHINGTON — A former U.S. ambassador of religious liberty. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to the Vatican and the president of The Catholic Supporters, who included organizations such recently ruled that Catholic institutions must provide health University of America were among 300 signers as Catholics United and Catholic Democrats, insurance that offers sterilizations, abortion inducing drugs, of a letter who called President Barack Obama’s said it was a viable response that would keep and contraceptives. This is a direct attack on the religious revision to a federal contraceptive mandate conscience rights intact and address the health liberty of Catholic institutions which serve ALL people, not just “unacceptable” and said it remains a “grave vio- care needs of women. Catholics. lation of religious freedom and cannot stand.” Still others who opposed the contraceptive As we have read, on Friday, Feb. 10 President Obama offered On Feb. 10, Obama said religious employers mandate said the revision could be a step in the some changes to the original HHS ruling. Instead of Catho- could decline to cover contraceptives if they right direction but needed more study because lic institutions having to provide the objectionable coverage, were morally opposed to them, but the health many questions “remained unanswered.” the insurance companies would do it. -

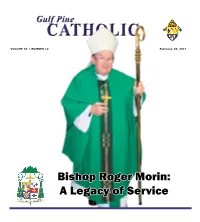

Bishop Roger Morin: a Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P

Gulf Pine CATHOLIC VOLUME 34 / NUMBER 12 February 10, 2017 Bishop Roger Morin: A Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P. Morin Third Bishop of Biloxi (2009 - 2016) Bishop Roger Paul Morin was Orleans. In 1973, he was appointed associate director of Bishop Morin received the Weiss Brotherhood Award installed as the third Bishop of Biloxi the Social Apostolate and in 1975 became the director, presented by the National Conference of Christians and on April 27, 2009, at the Cathedral of responsible for the operation of nine year-round social Jews for his service in the field of human relations. the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin service centers sponsored by the archdiocese. Bishop Bishop Morin was a member of the USCCB’s Mary by the late Archbishop Pietro Morin holds a master of science degree in urban studies Subcommittee on the Catholic Campaign for Human February 10, 2017 • Bishop Morin Sambi, Apostolic Nuncio to the from Tulane University and completed a program in Development 2005-2013, and served as Chairman 2008- United States, and Archbishop 1974 as a community economic developer. He was in 2010. During that time, he also served as a member of Thomas J. Rodi, Metropolitan Archbishop of Mobile. residence at Incarnate Word Parish beginning in 1981 the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human A native of Dracut, Mass., he was born on March 7, and served as pastor there from 1988 through April 2002. Development and the Committee for National 1941, the son of Germain J. and Lillian E. Morin. He has Bishop Morin is the Founding President of Second Collections. -

The Church Today, October 17, 2016

CHURCH TODAY Volume XLVII, No. 10 www.diocesealex.org Serving the Diocese of Alexandria, Louisiana Since 1970 October 17, 2016 O N T H E INSIDE Welcome Bishop David Talley, coadjutor for the Diocese of Alexandria Pope Francis has appointed Bishop David P. Talley, auxiliary bishop of the Atlanta Archdiocese, to serve the people of the Diocese of Alexandria, Louisiana, as coadjutor bishop to Bishop Ronald P. Herzog. Read more on page 3. Bishop’s Golf Tournament raises more than $30,000 for seminarian education Twenty-seven teams came out to enjoy the beautiful fall weather and to play a round of golf with friends at the annual Invitational Bishop’s Golf Tourna- Catch up with Jesus ment Oct. 10. More than $30,000 was raised. See pages 10-11. Students from St. Joseph Catholic School in Plaucheville wear their “Catch Up with Jesus” fall festival t-shirts for their school fair held Oct. 8-9. Schools and churches throughout the diocese have hosted fall fairs and festivals during October. See pages 12-13 for more celebrations during the month of October. PAGE 2 CHURCH TODAY OCTOBER 17, 2016 Presidential election politics have sunk to an all-time low Critics say candidates need to step out of the gutter; focus on more pressing needs By Rhina Guidos dent. Catholic News Service In response, two members of the advisory group, Father (CNS) -- Christopher J. Hale, Frank Pavone, national director executive director for Washing- of Priests for Life, and Janet Mo- ton’s Catholics in Alliance for the rana, co-founder of the Silent No Common Good, said the Oct. -

Diocese Celebrates Golden Jubilee with “Magnificent” Mass by Laura Deavers Vost of the Diocese of Lake Charles, Bishop Michael G

THE CATHOLIC November 16, 2011 C Vol. 49, No. 20ommentator SERVING THE DIOCESE OF BATON ROUGE SINCE 1962 thecatholiccommentator.org Bishop Robert W. Muench, along with the bishops of Louisiana, two bishops who were born in the Baton Rouge Diocese, and the priests of the Diocese of Baton Rouge gather in the sanctuary at the 50th Anniversary Mass of Thanksgiving held Nov. 6 at the Baton Rouge River Center Arena. Photo by Laura Deavers | The Catholic Commentator Diocese celebrates golden jubilee with “magnificent” Mass By Laura Deavers vost of the Diocese of Lake Charles, Bishop Michael G. Daughters of the Americas, Knights and Ladies of St. Editor Duca of the Diocese of Shreveport, Auxiliary Bishop Peter Claver, Knights and Ladies of the Equestrian Shelton J. Fabre of the Archdiocese of New Orleans and Order of the Holy Sepulchre, Serra Club, Society of St. “Magnificent!” The one word spoken by Kay Eads as Abbot Justin Brown OSB of St. Joseph Seminary Col- Vincent de Paul, and Boy and Girl Scouts. Employees she left the 50th Anniversary Mass of the Diocese of lege in St. Benedict. of the Catholic Life Center processed next representing Baton Rouge Nov. 6 expressed the opinion of those at- More than 1,500 people participated in the seven the many ministries of the diocese. tending this special Mass of Thanksgiving marking the processions that began the celebration. Dina Martinez Great attention was paid to many details of the Mass. end of the jubilee year of celebration. and Deacon Dan Borné, who told the story of the Dio- The processional cross, which was carried by Cecil The Mass was held at the Baton Rouge River Cen- cese of Baton Rouge, encouraged those watching the Harleaux, who worked for all five bishops of this dio- ter Arena to accommodate the thousands who would processions to be welcoming and festive, as they would cese, was a crucifix purchased by Bishop Joseph V. -

The Most Reverend David P. Talley Bishop, Catholic Diocese of Memphis in Tennessee

The Most Reverend David P. Talley Bishop, Catholic Diocese of Memphis in Tennessee The Most Reverend David P. Talley (69) was appointed by His Holiness Pope Francis as the sixth Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Memphis in Tennessee on March 5, 2019, and was installed on April 2, 2019. Bishop Talley, originally from Columbus, Ga., was raised a Southern Baptist, but converted to Catholicism while a student at Auburn University. He was received into the Catholic Church at age 24 at Saint Mary Church in Opelika, Ala. His family members remain Baptists, Catholics, Church of Christ, Lutherans, United Methodists and those seeking the light of God. After his studies at Auburn, he later obtained a Master's degree in social work from the University of Georgia and spent time as a case worker in Fulton County, Ga., protecting children from abuse and neglect. He studied for the priesthood at Saint Meinrad Seminary and School of Theology in Indiana and obtained a Master of Divinity degree in 1989. Bishop Talley was ordained to the priesthood on June 3, 1989, at the Cathedral of Christ the King in Atlanta, Ga. As a Priest of the Archdiocese of Atlanta, Bishop Talley served as a Parochial Vicar, Administrator and Pastor of a number of parishes. From 1993 to 1998, Bishop Talley studied at Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, Italy, where he obtained a Doctorate in Canon Law. Bishop Talley also served as Judicial Vicar of the Tribunal, as the Director of Vocations and as Chancellor of the Archdiocese. In 2001, he was named a Chaplain to His Holiness Saint John Paul II, with the title "Monsignor." One of his roles in the Atlanta Archdiocese was as chaplain to the disabilities ministry. -

Softball Results Horseshoe Results Golf Results

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF LOUISIANA STATE COUNCIL KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS OCTOBER 2011 Softball Results Horseshoe Results October 1-30 Respect Life Month October 10 Deadline - Supreme Per Capita October 10 Columbus Day Observed Golf Results October 15 Deadline - Family of the Month October 16 Major Degree - Luling Council 2409, Host October 23 Major Degree - Thibodaux Council 1114, Host October 30 Major Degree - Iowa Council 3006, Host October 31 Deadline-Order Free Throw Kits October 31 Deadline-Order Substance Abuse Kits November 1 Feast of All Saints Day November 1 CYLA Info Mailed to all High Schools in State November 2 Feast of All Souls Day November 3 Deadline - Area Soccer Winners to State Office November 5 State Nine Ball Tournament Lafayette Nov 6-26 Silver Rose Program November 8 ELECTION DAY November 11 Veterans Day November 13 State Soccer Challenge Baton Rouge November 13 Major Degree - Slidell Council 2732, Host November 15 Deadline - Family of the Month November 15 Deadline - District Cook-Off November 24 Thanksgiving December 1 Deadline - Submit Articles & Photos for Louisiana Knight December 1 Deadline - Council CYLA Chair submitted to CYLA Chairman December 2-4 State Family Meeting Sulphur December 15 Deadline - Family of the Month December 15 Deadline - Area Cook-Off December 25 CHRISTmas January 1 New Years Day January 10 Deadline - Payment Supreme Catholic Advertising January 11 Deadline - Council Substance Abuse Poster Contest January 15 State Per Capita Mailed to F.S. January 15 Deadline - CYLA Applications to Councils -

Two Ordained to Priesthood for Diocese of Lake Charles LAKE CHARLES – the Most Reverend Glen He Acts Openly and Truthfully

Vol. 41, No. 9 Two ordained to priesthood for Diocese of Lake Charles LAKE CHARLES – The Most Reverend Glen he acts openly and truthfully. At the heart of John Provost ordained Reverend Jay Alexius this transparency is his desire to preach Je- and Reverend Ruben Villarreal to the priest- sus Christ, purely and simply. Only in this hood for the Diocese of Lake Charles on Satur- way can the light of Jesus Christ shine in all day, June 27, during Mass in the Cathedral of its brilliance. The reason the light can shine the Immaculate Conception. through his human frailties is because St. Paul Father Alexius celebrated his first Mass has removed any obstacle of self. There is no on Saturday, June 27, in Immaculate Heart pretense to veil the sunlight of Christ’s truth. of Mary Catholic Church in Lake Charles, his Continuing the Bishop said, “St. Paul con- adoptive parish, while Father Villarreal was cludes, ‘We hold this treasure in earthen ves- the celebrant of his first Mass on Sunday, June sels, that the surpassing power may be of God 28, in his home parish of St. Lawrence in Ray- and not from us’. St. Paul never speaks in detail mond. about his specific weaknesses. Even the exact Before the closing prayer of Saturday’s or- meaning of his proverbial “thorn in the flesh” dination liturgy, Deacon George Stearns, Di- remains a mystery. Yet, we are never in doubt ocesan Chancellor, read the announcement that St. Paul knows the sort of clay from which of first-time appointments for the newly or- he is made and that in this self-knowledge the dained. -

Parishes Begin to Rebuild Expansion Helps Sanctuary for Life Serve Need

THE CATHOLIC Msgr. Lefebvre remembered Page 3 September 30,ommentator 2016 Vol. 54, No. 17 SERVING THE DIOCESE OF BATON ROUGE SINCE 1963 thecatholiccommentator.org C RETURNING TO NORMAL Parishes begin to rebuild By Debbie Shelley and Rachele Smith The Catholic Commentator Contract workers from Belfor Prop- erty Restoration have been working 14 hours a day to get the facilities at St. Alphonsus Church and School in Greenwell Springs up and running. The first priority was getting its school operational first, according to St. Alphonsus Pastor Father Mi- chael Moroney. Contractors replaced flooring and painted walls in flood- ed rooms and repaired the cafeteria. The school opened on Aug. 29, but the Workers with Belfor Property Restoration replace flooring in St. Alphonsus Church in Greenwell Springs. Workers at the school offices are in various stages of church and St. Alphonsus School have been working tirelessly to get the campus fully operational after historic flooding hit SEERI PAGE PA 23 SHES the Baton Rouge area in August. Photo by Debbie Shelley | The Catholic Commentator Commentator Expansion helps Sanctuary for Life serve need By Richard Meek “To all of the people present and about 10 years ago, David Aguillard debuts new The Catholic Commentator others who have been part of this met with then-Vicar General Fa- mission of Sanctuary for Life where ther Than Vu and they quickly found feature From humble beginnings rooted in we honor all human life and respect themselves questioning the mission of a shuttered rectory, Sanctuary for Life all human life, (today) should give us Catholic Charities. -

The Real Powers Behind President Barack Obama by Karen Hudes

The Real Powers Behind President Barack Obama By Karen Hudes Tuesday, December 31, 2013 8:02 (Before It's News) From Karen Hudes Facebook page: Barack Obama is truly not the President of the United States. He is not a powerful person at all. Rather, he is a front man for more powerful entities that hide in the shadows. The real power in the world is not the United States, Russia, or even China. It is Rome. The Roman Catholic Church (Vatican) is the single most powerful force in the world. However, the Vatican has been under the control of it’s largest all-male order, the Jesuits. The Jesuits were created in 1534 to serve as the “counter-reformation” — the arm of the Church that would help to fight the Muslims and the Protestant Reformers. However, they fought with espionage. The Jesuits were expelled from at least 83 countries and cities for subversion, espionage, treason, and other such things. Samuel Morse said that the Jesuits were the foot soldiers in the Holy Alliance (Europe and the Vatican) plan to destroy the United States (Congress of Vienna). Marquis Lafayette stated that the Jesuits were behind most of the wars in Europe, and that they would be the ones to take liberty from the United States. The head of the Jesuit Order is Adolfo Nicholas. His title is Superior General of the Jesuits. The use of the rank “general” is because the Jesuits are, in reality, a military organization. Nicholas, as the Jesuit General, is the most powerful man in the world. -

Winter 2017 • Vol

On the Hill Winter 2017 • Vol. 56:1 Infirmary renovation complete Abbey Press will close two divisions in 2017 Day of Service expands to 10 locations Cover: Seminarians Joseph Stoverink and Colby Elbert play disc golf on the new course installed on campus. On the Hill Winter 2017 • Vol. 56:1 FEATURES 2-3 . .Monastery News 4 . .Abbey Press Closing Two Divisions 6-7 . .High School Youth Conference in MO 8 . .Lilly Grant for Young Adult Initiative 9 . .New School Appointments 10 . .IPP Advisory Board ALUMNI 12 . .Day of Service 2017 13 . .Alumni Reunion 2017 14-15 . .Alumni Eternal and News 16 . .Theology After Hours On the Hill is published four times a year by Saint Meinrad Archabbey and Seminary and School of Theology. The newsletter is also available online at: www.saintmeinrad.edu/onthehill Editor: . .Mary Jeanne Schumacher Copywriters: . .Krista Hall & Tammy Schuetter Send changes of address and comments to: The Editor, The Development Office, Saint Meinrad Archabbey and Seminary & School of Theology, Deacon Colby Elbert, as Snoopy, peeks out from beneath the stage 200 Hill Drive, St. Meinrad, IN 47577, (812) 357-6501 • Fax (812) 357-6759, [email protected] curtain during the St. Nicholas Banquet skit on December 1. www.saintmeinrad.edu, © 2017, Saint Meinrad Archabbey Find more photos at http://saint-meinrad.smugmug.com Monks’ Personals Archabbot Kurt Stasiak attended the Fr. Cassian Folsom resigned as prior of Congress of Abbots in Rome on Monastero di San Benedetto in Norcia, September 2-23. The abbots elected Italy, on November 22. He is the founder Online Store Abbot Gregory Polan of Conception of the community and served 18 years as Visit the Scholar Shop’s Abbey, Conception, MO, to an eight-year prior. -

The Work of the Holy Land Commission

SEPU TI LC C R N I A Southeastern Lieutenancy H S I S E Of the United States I R R O Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem T S S O E L U Y Q M E NEWS I T O A D N R I O Sir Anthony J. Capritto, III, KGCHS, Lieutenant December, 2010 Volume 23, No. 3 James T. Myers, KCHS, Editor The Work of the Holy Land Commission Members who attended the 2010 annual meeting will remember the presentation by Sir Thomas McKiernan, KCSG, KGCHS, a member of the Grand Magisterium and the Holy Land Commission. Sir Tom has kindly provided us with a report and photos from his recent trip to the Holy Land. Sir Tom writes, “Here is the situation. On the Holy Land Commission there are three people. I am the scribe, that is, taking the notes and preparing the report for the Grand Magisterium and Dr. Christa von Siemens, President of the Commission is our chief photographer. Christa takes hundreds of photographs of projects in various states of completion, proposed projects for future years, people, buildings, children, plays and performances given by children. Generally only a few of the photos are used for the Grand Magisterium meetings…” “Most of the projects are school renovations and improvements to nuns’ convents and priests’ houses and various modernization of plumbing, electric service, sanitary/bathrooms. This year and next we have two major projects, a new parish church in Sir Tom With Hashimi School Children Aquaba in the South of Jordan and renovations of the sanitary facilities in the Patriarchal seminary in Beit Jala.