Cacv3678 in the Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superior Court of Québec 2010 2014 Activity Report

SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS The drawing on the cover is the red rosette found on the back of the collar of the judge’s gown. It was originally used in England, where judges wore wigs: their black rosettes, which were applied vertically, prevented their wigs from rubbing against and wearing out the collars of their gowns. Photo on page 18 Robert Levesque Photos on pages 29 and 30 Guy Lacoursière This publication was written and produced by the Office of the Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Québec 1, rue Notre-Dame Est Montréal (Québec) H2Y 1B6 Phone: 514 393-2144 An electronic version of this publication is available on the Court website (www.tribunaux.qc.ca) © Superior Court of Québec, 2015 Legal deposit – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2015 Library and Archives Canada ISBN: 978-2-550-73409-3 (print version) ISBN: 978-2-550-73408-6 (PDF) CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 04 A Message from the Chief Justice 06 The Superior Court 0 7 Sectors of activity 07 Civil Chamber 08 Commercial Chamber 10 Family Chamber 12 Criminal Chamber 14 Class Action Chamber 16 Settlement Conference Chamber 19 Districts 19 Division of Montréal 24 Division of Québec 31 Case management, waiting times and priority for certain cases 33 Challenges and future prospects 34 Court committees 36 The Superior Court over the Years 39 The judges of the Superior Court of Québec November 24, 2014 A message from the Chief Justice I am pleased to present the Four-Year Report of the Superior Court of Québec, covering the period 2010 to 2014. -

Annual Review of Civil Litigation

ANNUAL REVIEW OF CIVIL LITIGATION 2019 THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE TODD L. ARCHIBALD SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (ONTARIO) 30839744 Discovery as a Forum for Persuasive Advocacy: Art and Science of Persuasion Ð Chapter IX 1 TODD ARCHIBALD,ROGER B. CAMPBELL AND MITCHELL FOURNIE The flash and dash of the courtroom is exhilarating for the lawyer but dangerous for the client. Accordingly, the truly successful lawyer will take his cases there only seldom. When he does go, he will go highly prepared; and that high level of preparation will be made possible by the apparently dull, but fascinatingly powerful tool, of discovery. And when a lawyer has been successful in keeping his client out of a trial, it will most often have been the same tool, discovery, which will have helped him do it.1 I. DISCOVERY AS A FORUM FOR PERSUASIVE ADVOCACY The image of the persuasive litigator is often associated with trials. It is an image that evokes the courtroom scenario and the pressures that accompany it. Here, witnesses are tenaciously cross-examined, answers are carefully assessed, credibility is gauged, and lawyers make their opening and closing addresses in full view of the judge, jury, and public. It is an image that draws on the solemnity and magnitude of trial, where the potential for settlement has long passed and a verdict or judgment is the only potential outcome. It is from this situation, at the end of the litigation process, that our notions of persuasive advocacy are often derived. In this ninth installment of the Art and Science of Persuasion, we look at how persuasive advocacy can and must extend beyond the courtroom. -

National Directory of Courts in Canada

Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE National Directory of Courts in Canada August 2000 Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Statistics Statistique Canada Canada How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Information and Client Service, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-9023 or 1 800 387-2231). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our Web site. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1 800 700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1 800 889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Web site www.statcan.ca Ordering and subscription information This product, Catalogue no. 85-510-XPB, is published as a standard printed publication at a price of CDN $30.00 per issue. The following additional shipping charges apply for delivery outside Canada: Single issue United States CDN $ 6.00 Other countries CDN $ 10.00 This product is also available in electronic format on the Statistics Canada Internet site as Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE at a price of CDN $12.00 per issue. To obtain single issues or to subscribe, visit our Web site at www.statcan.ca, and select Products and Services. All prices exclude sales taxes. The printed version of this publication can be ordered by • Phone (Canada and United States) 1 800 267-6677 • Fax (Canada and United States) 1 877 287-4369 • E-mail [email protected] • Mail Statistics Canada Dissemination Division Circulation Management 120 Parkdale Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0T6 • And, in person at the Statistics Canada Reference Centre nearest you, or from authorised agents and bookstores. -

Relevance and Proportionality in the Rules of Civil Procedure in Canadian Jurisdictions

T HE S EDONA C ONFERENCE ® W ORKING G ROUP S ERIES SM THE SEDONA CANADA SM COMMENTARY ON PROPORTIONALITY IN ELECTRONIC DISCLOSURE & D ISCOVERY A Project of The Sedona Conference ® Working Group 7 (WG7) Sedona Canada SM OCTOBER 2010 Copyright © 2010, The Sedona Conference ® The Sedona Canada SM Commentary on Proportionality in Electronic Disclosure and Discovery Working Group 7 “Sedona Canada SM ” OCTOBER 2010 P UBLIC COMMENT VERSION Author: The Sedona Conference ® Commentary Drafting Team : Sedona Canada SM Editorial Board: Todd J. Burke Justice Colin L. Campbell Justice Colin L. Campbell Robert J. C. Deane (chair) Jean-François De Rico Peg Duncan Peg Duncan Kelly Friedman (ex officio) Edmund Huang Karen B. Groulx Kristian Littman Dominic Jaar Edwina Podemski Glenn Smith James T. Swanson The Sedona Conference ® also wishes to acknowledge the members of The Sedona Conference ® Working Group 7 (“Sedona Canada SM ”) who contributed to the dialogue while this Commentary was a work-in-progress. We also wish to thank all of our Working Group Series SM Sponsors, whose support is essential to The Sedona Conference’s ® ability to develop Working Group Series SM publications such as this. For a complete listing of our Sponsors, click on the “Sponsors” navigation bar on the home page of our website at www.thesedonaconference.org . Copyright © 2010 The Sedona Conference ® All Rights Reserved. REPRINT REQUESTS: Requests for reprints or reprint information should be directed to Richard Braman, Executive Director of The Sedona Conference ®, at [email protected] or 1-866-860-6600. The opinions expressed in this publication, unless otherwise attributed, represent consensus views of the members of The Sedona Conference ® Working Group 7 (“Sedona Canada SM ”) . -

Court File No. 1801-04745 Court Court of Queen's

DocuSign Envelope ID: A75076B7-D1B5-4979-B9B7-ABB33B19F417 Clerk’s stamp: COURT FILE NO. 1801-04745 COURT COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CENTRE CALGARY PLAINTIFF HILLSBORO VENTURES INC. DEFENDANT CEANA DEVELOPMENT SUNRIDGE INC., BAHADUR (BOB) GAIDHAR, YASMIN GAIDHAR AND CEANA DEVELOPMENT WESTWINDS INC. PLAINTIFFS BY COUNTERCLAIM CEANA DEVELOPMENT SUNRIDGE INC., BAHADUR (BOB) GAIDHAR AND YASMIN GAIDHAR DEFENDANTS BY COUNTERCLAIM HILLSBORO VENTURES INC., NEOTRIC ENTERPRISES INC., KEITH FERREL AND BORDEN LADNER GERVAIS LLP DOCUMENT BRIEF OF LAW AND ARGUMENT OF THE APPLICANT HILLSBORO VENTURES INC. ADDRESS FOR SERVICE AND Dentons Canada LLP CONTACT INFORMATION OF PARTY Bankers Court FILING THIS DOCUMENT 15th Floor, 850 – 2nd Street SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 0R8 Attn: Derek Pontin / John Regush Ph. (403) 268-6301 / 7086 Fx. (403) 268-3100 File No.: 559316-3 Brief of Law and Argument of the Applicant in respect of an application to be heard by the Honourable Madam Justice Eidsvik, scheduled on June 2 and 3, 2021 NATDOCS\54598355\V-1 DocuSign Envelope ID: A75076B7-D1B5-4979-B9B7-ABB33B19F417 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................1 II. FACTS..............................................................................................................................................1 a. The Application Record....................................................................................................................1 -

Conservatives, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the Constitution: Judicial-Government Relations, 2006–2015 Christopher Manfredi Mcgill University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by York University, Osgoode Hall Law School Osgoode Hall Law Journal Article 6 Volume 52, Issue 3 (Summer 2015) Conservatives, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the Constitution: Judicial-Government Relations, 2006–2015 Christopher Manfredi McGill University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Law Commons Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Manfredi, Christopher. "Conservatives, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the Constitution: Judicial-Government Relations, 2006–2015." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 52.3 (2015) : 951-984. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol52/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Conservatives, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the Constitution: Judicial-Government Relations, 2006–2015 Abstract Three high-profile government losses in the Supreme Court of Canada in late 2013 and early 2014, combined with the government’s response to those losses, generated a narrative of an especially fractious relationship between Stephen Harper’s Conservative government and the Court. This article analyzes this narrative more rigorously by going beyond a mere tallying of government wins and losses in the Court. Specifically, it examines Charter-based invalidations of federal legislation since 2006, three critical reference opinions rendered at the government’s own request, and two key judgments delivered in the spring of 2015 concerning Aboriginal rights and the elimination of the long-gun registry. -

Yukon (Government Of) V. Yukon Zinc Corporation, 2020 YKSC 16 May 26

SUPREME COURT OF YUKON Citation: Yukon (Government of) v. Date: 20200526 Yukon Zinc Corporation, 2020 YKSC 16 S.C. No. 19-A0067 Registry: Whitehorse BETWEEN GOVERNMENT OF YUKON as represented by the Minister of the Department of Energy, Mines and Resources PETITIONER AND YUKON ZINC CORPORATION RESPONDENT Before Madam Justice S.M. Duncan Appearances: John T. Porter and Laurie A. Henderson Counsel for the Petitioner No one appearing Yukon Zinc Corporation No one appearing Jinduicheng Canada Resources Corporation Limited H. Lance Williams Counsel for Welichem Research General Partnership John Sandrelli and Cindy Cheuk Counsel for PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc. REASONS FOR JUDGMENT (Application by Welichem Opposing Partial Disclaimer) INTRODUCTION [1] Welichem Research General Partnership, (“Welichem”), is a secured creditor of the debtor company, Yukon Zinc Corporation (“YZC”). PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc. Yukon (Government of) v. Yukon Zinc Corporation, 2020 YKSC 16 2 (the “Receiver”) was appointed by Court Order dated September 13, 2019, as the Receiver of YZC. Welichem brings an application for the following relief: 1) the Receiver’s notice of partial disclaimer of the Master Lease is a nullity and of no force and effect; 2) the Receiver has affirmed the Master Lease and is bound by the entirety of its terms; and 3) the Receiver must pay to Welichem all amounts owing under the Master Lease from the date of the Receiver’s appointment and ongoing. BACKGROUND [2] The background set out in Yukon (Government of) v. Yukon Zinc Corporation, 2020 YKSC 15, applies here, in addition to the following facts. [3] On March 1, 2018, YZC sold 572 items, comprising most of the equipment, tools, vehicles and infrastructure at the Wolverine Mine (the “Mine”) to Maynbridge Capital Inc. -

Summary of the Presentation of Chief Judge

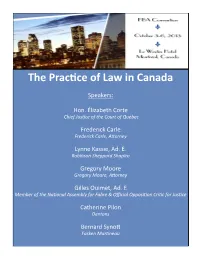

The Practice of Law in Canada Speakers: Hon. Élizabeth Corte Chief Justice of the Court of Québec Frederick Carle Frederick Carle, Attorney Lynne Kassie, Ad. E. Robinson Sheppard Shapiro Gregory Moore Gregory Moore, Attorney Gilles Ouimet, Ad. E Member of the National Assembly for Fabre & Official Opposition Critic for Justice Catherine Pilon Dentons Bernard Synott Fasken Martineau FAIRFAX BAR ASSOCIATION CLE SEMINAR Any views expressed in these materials are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any of the authors’ organizations or of the Fairfax Bar Association. The materials are for general instructional purposes only and are not offered for use in lieu of legal research and analysis by an appropriately qualified attorney. *Registrants, instructors, exhibitors and guests attending the FBA events agree they may be photographed, videotaped and/or recorded during the event. The photographic, video and recorded materials are the sole property of the FBA and the FBA reserves the right to use attendees’ names and likenesses in promotional materials or for any other legitimate purpose without providing monetary compensation. Court of Québec The Honourable Élizabeth Corte Chief Judge of the Court of Québec Called to the Bar on January 11, 1974, Élizabeth Corte practised her profession exclusively at the Montreal offices of Legal Aid. At the time of her appointment to the Cour du Québec, she was the assistant director of legal services in criminal and penal affairs. In addition to teaching criminal law at École du Barreau de Montréal since 1986, she has given courses on criminal procedure and evidence at Université de Montréal's École de criminologie. -

Federal Court Cour Fédérale

Federal Court Cour fédérale THE HONOURABLE SEAN J. HARRINGTON THE FEDERAL COURTS JURISDICTION CONFERENCE STEERING COMMITTEE PERSONAL REMINISCENCES At our Jurisdiction Conference Steering Committee meeting, held on Thursday, 22 July 2010, it was agreed that we should focus on the present and the future. However, it was also thought that some mention should be made of the original raison d’être of our courts and their history. As Chief Justice Lutfy is fond of pointing out, Mr. Justice Hughes and I are probably the only two sitting judges who not only appeared in the courts from day one, but also appeared in the Exchequer Court! This got me to thinking how important the Federal Courts were in my practice, and gave me a bad case of nostalgia. Maritime law has always been my speciality (although my first appearance in the Exchequer Court was before President Jackett on an Anti-Combines matter). The Federal Court had many advantages over provincial courts. Its writ ran nationwide. Cargo might be discharged in one province and delivered in another. Provincial courts were less prone at that time to take jurisdiction over defendants who could not be personally served within the jurisdiction. Provincial bars were very parochial, and in the days before inter-provincial law firms, if it were not for the Federal Court, maritime players and their underwriters sometimes had to hire two or more different law firms to pursue what was essentially one cause of action. Doc: Federal Courts_Personal Reminiscences_SJH_18-Aug-10.doc Page: 1 The Crown was a much bigger player in maritime matters in the 1970s. -

Delaying Justice Is Denying Justice: an Urgent Need to Address Lengthy Court Delays in Canada (Final Report), June 2017

DELAYING JUSTICE IS DENYING JUSTICE An Urgent Need to Address Lengthy Court Delays in Canada Final report of the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs The Honourable Bob Runciman, Chair The Honourable George Baker, P.C., Deputy Chair SBK>QB SK>Q June 2017 CANADA This report may be cited as: Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Delaying Justice is Denying Justice: An Urgent Need to Address Lengthy Court Delays in Canada (Final Report), June 2017. For more information please contact us by email [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-6087 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: The Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Senate, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: www.senate-senat.ca/lcjc.asp Ce rapport est également offert en français Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 Priority Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER ONE - INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 9 Canada’s Critical Delay Problem ............................................................................................................... 9 The Committee’s Study .......................................................................................................................... -

Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:21 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Was Duplessis Right? Roderick A. Macdonald The Legacy of Roncarelli v. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Article abstract L’héritage de l’affaire Roncarelli c. Duplessis, 1959-2009 Given the inclination of legal scholars to progressively displace the meaning of Volume 55, Number 3, September 2010 a judicial decision from its context toward abstract propositions, it is no surprise that at its fiftieth anniversary, Roncarelli v. Duplessis has come to be URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1000618ar interpreted in Manichean terms. The complex currents of postwar society and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1000618ar politics in Quebec are reduced to a simple story of good and evil in which evil is incarnated in Duplessis’s “persecution” of Roncarelli. See table of contents In this paper the author argues for a more nuanced interpretation of the case. He suggests that the thirteen opinions delivered at trial and on appeal reflect several debates about society, the state and law that are as important now as half a century ago. The personal socio-demography of the judges authoring Publisher(s) these opinions may have predisposed them to decide one way or the other; McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill however, the majority and dissenting opinions also diverged (even if unconsciously) in their philosophical leanings in relation to social theory ISSN (internormative pluralism), political theory (communitarianism), and legal theory (pragmatic instrumentalism). Today, these dimensions can be seen to 0024-9041 (print) provide support for each of the positions argued by Duplessis’s counsel in 1920-6356 (digital) Roncarelli given the state of the law in 1946. -

Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arran

■ Diversifying the bar: lawyers make history Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present Click here to download Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 1: 1797 to 1941 For each lawyer, this document offers some or all of the following information: name gender year and place of birth, and year of death where applicable year called to the bar in Ontario (and/or, until 1889, the year admitted to the courts as a solicitor; from 1889, all lawyers admitted to practice were admitted as both barristers and solicitors, and all were called to the bar) whether appointed K.C. or Q.C. name of diverse community or heritage biographical notes name of nominating person or organization if relevant sources used in preparing the biography (note: living lawyers provided or edited and approved their own biographies including the names of their community or heritage) suggestions for further reading, and photo where available. The biographies are ordered chronologically, by year called to the bar, then alphabetically by last name. To reach a particular period, click on the following links: 1941-1950, 1951-1960, 1961-1970, 1971-1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-. To download the biographies of lawyers called to the bar before 1941, please click Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present For more information on the project, including the set of biographies arranged by diverse community rather than by year of call, please click here for the Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History home page.