Ground Handling Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concession Fee Deferral Burgas

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 14.8.2020 C(2020) 5713 final In the published version of this decision, PUBLIC VERSION some information has been omitted, pursuant to articles 30 and 31 of Council This document is made available for Regulation (EU) 2015/1589 of 13 July 2015 information purposes only. laying down detailed rules for the application of Article 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, concerning non-disclosure of information covered by professional secrecy. The omissions are shown thus […] Subject: State Aid SA.58095 (2020/N) — Bulgaria — Covid-19: Concession fee deferral for Burgas and Varna airports Excellency, 1. PROCEDURE (1) By letter of 17 July 2020, registered on 20 July 20201, the Bulgarian authorities notified in accordance with Article 108(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), their intention to grant aid to the operator of Burgas and Varna airports. (2) In their notification, the Bulgarian authorities have exceptionally accepted to waive their right under Article 342 TFEU in conjunction with Article 3 of Regulation 1/19582 and to obtain a Commission decision on the matter in the English language. (3) By email of 31 July 2020, the Bulgarian authorities completed their notification with additional information. 1 Under State aid case number SA.58095. 2 Regulation No 1 determining the languages to be used by the European Economic Community, OJ 17, 6.10.1958, p. 385. Екатерина ЗАХАРИЕВА Министър на външните работи ул.„Ал. Жендов“ No2 1113 СОФИЯ/Sofia БЪЛГАРИЯ/BULGARIE Commission européenne/Europese Commissie, 1049 Bruxelles/Brussel, BELGIQUE/BELGIË - Tel. -

NATIONAL COMPANY INDUSTRIAL ZONES Strategic Partner for Investors in Bulgaria OVERVIEW

NATIONAL COMPANY INDUSTRIAL ZONES Strategic Partner for Investors in Bulgaria OVERVIEW NATIONAL COMPANY INDUSTRIAL ZONES (NCIZ) A 100% state-owned company with a sole shareholder the Ministry of Economy of Bulgaria Specialized in • Industrial park development • Management of industrial zones • Providing additional services for investors Main activities: • Development of industrial zones in line with the latest standards • Encouraging investments in sectors with high added value • Creating favourable conditions for investment 2 OVERVIEW Four operating zones • Free Zone Ruse • Free Zone Svilengrad • Industrial Zone Vidin • Transit Trade Zone – Varna Two newly constructed zones • Sofia – Bozhurishte Economic Zone • Industrial & Logistics Park – Burgas A total of 9 projects Three zones under development • 6 804 095 m² total area • Industrial Zone Karlovo • 76 409 m² built-up area • Industrial Zone Telish /Pleven/ • 240 500 m² open-air warehouses • Industrial Zone Varna West 3 SOFIA-BOZHURISHTE ECONOMIC ZONE Total area: 2 665 595 m² Location • Sofia City Center 15 km away • Sofia Airport 23 km away • 5 km from a highway to Greece • 2 km from a highway to Serbia • 30 km from a highway to the Black Sea • Next to the international road connecting Europe with Turkey and Asia • Direct connection to the railway network 4 INVESTORS IN SOFIA-BOZHURISHTE ECONOMIC ZONE Sofia-Bozhurishte Economic Zone has already attracted 20 investors, operating in a number of sectors, including Automotive Industry, High Tech, Warehousing & Logistics. The companies are European so far - Bulgarian, German, Danish, Greek. Investments in the zone: 350 mln BGN Job openings: exceeding 1060. 5 INVESTORS IN SOFIA-BOZHURISHTE ECONOMIC ZONE JYSK Distribution Center Bozhurishte Total amount of the investment: 100 million EUR over the next 2 to 5 years Project scale: 300 000 m2 land The Danish furniture and interiors company JYSK Nordic will implement a large-scale investment project in Sofia – Bozhurishte Economic Zone by constructing the largest distribution center in South East Europe. -

Update of the List of Border Crossing Points Referred to In

C 244/22 EN Official Journal of the European Union 26.7.2014 Update of the list of border crossing points referred to in Article 2(8) of Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code) (OJ C 316, 28.12.2007, p. 1; OJ C 134, 31.5.2008, p. 16; OJ C 177, 12.7.2008, p. 9; OJ C 200, 6.8.2008, p. 10; OJ C 331, 31.12.2008, p. 13; OJ C 3, 8.1.2009, p. 10; OJ C 37, 14.2.2009, p. 10; OJ C 64, 19.3.2009, p. 20; OJ C 99, 30.4.2009, p. 7; OJ C 229, 23.9.2009, p. 28; OJ C 263, 5.11.2009, p. 22; OJ C 298, 8.12.2009, p. 17; OJ C 74, 24.3.2010, p. 13; OJ C 326, 3.12.2010, p. 17; OJ C 355, 29.12.2010, p. 34; OJ C 22, 22.1.2011, p. 22; OJ C 37, 5.2.2011, p. 12; OJ C 149, 20.5.2011, p. 8; OJ C 190, 30.6.2011, p. 17; OJ C 203, 9.7.2011, p. 14; OJ C 210, 16.7.2011, p. 30; OJ C 271, 14.9.2011, p. 18; OJ C 356, 6.12.2011, p. 12; OJ C 111, 18.4.2012, p. 3; OJ C 183, 23.6.2012, p. 7; OJ C 313, 17.10.2012, p. -

2014 Fai World Championships for Space Models 2014 Fai Junior World Championships for Space Models

2014 FAI WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR SPACE MODELS 2014 FAI JUNIOR WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR SPACE MODELS These are th 20 World Space Modelling Championships for Seniors th 11 World Space Modelling Championships for Juniors th th 22 – 30 August, 2014 – Kaspichan, Bulgaria BULLETIN № 3 30 the June 2014 Kaspichan 2014 FAI WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS for SPACE MODELS 20th for SENIORS 11th for JUNIORS 22-30 august 2014 Kaspichan Bulgaria ORGANIZERS: By appointment of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) Organizers are: National Aero Club of Bulgaria Bulgarian Aeromodelling Federation Municipality of Kaspichan Space model Club “Modelist”, Kaspichan Director of the Championships: Mr. Stanev Plamen Sports Director: Mr. Ivanov Dimitar IT Service Manager: Mr. Yordanov Borislav Secretary of the Championships: Mrs. Stoyanova Sasha DESCRIPTION OF THE CHAMPIONSHIPS’ LOCATION: 2 Transportation: The World Championship shall be held in the municipality Kaspichan. Kaspichan is 20 km from the town of Shumen, where shall be registration and accommodation. Shumen is situated on the main road Sofia - Varna. Distance from Sofia to Shumen is 360 km, Varna - Shumen is 94 km and Varna - Ruse (125). The nearest international airports are in Varna (94 km), Burgas (155 km) and Sofia (360 km). Domestic flights: Flights to Sofia are served every day of the week at convenient hours. Flights are operated by the national carrier Bulgaria Air. On Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday the airline also operate combined package flights Sofia- Varna- Burgas. International flights: Austrian Airlines connects the Austrian capital Vienna to Varna every day of the week. The plane flies to Vienna at 13:30. WizzAir operates direct scheduled flights from Varna to London on Wednesday and Sunday. -

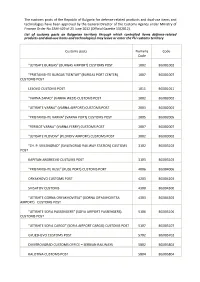

The Customs Posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for Defence-Related

The customs posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies have been approved by the General Director of the Customs Agency under Ministry of Finance Order No ZAM-429 of 25 June 2012 (Official Gazette 53/2012). List of customs posts on Bulgarian territory through which controlled items defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies) may leave or enter the EU customs territory Customs posts Numeric Code Code “LETISHTE BURGAS” (BURGAS AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 1002 BG001002 “PRISTANISHTE BURGAS TSENTAR” (BURGAS PORT CENTER) 1007 BG001007 CUSTOMS POST LESOVO CUSTOMS POST 1011 BG001011 “VARNA ZAPAD” (VARNA WEST) CUSTOMS POST 2002 BG002002 “LETISHTE VARNA” (VARNA AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 2003 BG002003 “PRISTANISHTE VARNA” (VARNA PORT) CUSTOMS POST 2005 BG002005 “FERIBOT VARNA” (VARNA FERRY) CUSTOMS POST 2007 BG002007 “LETISHTE PLOVDIV” (PLOVDIV AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 3002 BG003002 “ZH. P. SVILENGRAD” (SVILENGRAD RAILWAY STATION) CUSTOMS 3102 BG003102 POST KAPITAN ANDREEVO CUSTUMS POST 3103 BG003103 “PRISTANISHTE RUSE” (RUSE PORT) CUSTOMS PORT 4006 BG004006 ORYAKHOVO CUSTOMS POST 4203 BG004203 SVISHTOV CUSTOMS 4300 BG004300 “LETISHTE GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA” (GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA 4303 BG004303 AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA PASSENGERS” (SOFIA AIRPORT PASSENGERS) 5106 BG005106 CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA CARGO” (SOFIA AIRPORT CARGO) CUSTOMS POST 5107 BG005107 GYUESHEVO CUSTOMS POST 5702 BG005702 DIMITROVGRAD CUSTOMS OFFICE – SERBIAN RAILWAYS 5802 BG005802 KALOTINA CUSTOMS POST 5804 BG005804 -

Newsletter Issue No

Newsletter Issue No. 7 – February 2016 In this issue Editorial Editorial Andreas Gilsdorf, Robert Koch Institute, News from the AIRSAN Coordination Germany Recent meetings The current development in transmission of Zika virus infection, Recent developments particularly in South and Central American countries, is alarming. Table-top exercise in Tel Aviv (Israel) Given the high numbers of passengers travelling between Europe Second review of guidance material and America, the probability of European citizens getting infected Finalisation of the AIRSAN Training Tool is increasing. Finalisation of the AIRSAN Website We hope that AIRSAN can support the response to Zika virus Finalisation of dissemination activities infections similarly as it was possible during the time of the climax Preparation of the AIRSAN Final Report of the outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa. We would Final evaluation of the AIRSAN Project like to reinforce the useof the AIRSAN Communication Platform Other topics (where there is currently a discussion ongoing regarding infection control measures at European airports) or the updated AIRSAN Proposal of a user friendly version of the Bibliography, to get into exchange with each other and to have Passenger Locator Form access to relevant guidance material on the response of public A medical emergency landing and risk health threats in air tansport. assessment challenge for public health threats People from the AIRSAN Project News from the AIRSAN Coordination Cinthia Menel Lemos, Chafea Virgilijus Valentukevicius, EASA Astrid Milde-Busch, Robert Koch Institute, Airports at a glance Germany Burgas Airport and Varna Airport After almost 3 years of activities, the AIRSAN Project is now drawing to its close. -

Air Transport - a Source of Competitive Advantages of the Region

Marketing and Branding Research 5(2018) 206-216 MARKETING AND BRANDING RESEARCH WWW.AIMIJOURNAL.COM Air Transport - A Source of Competitive Advantages of the Region Keranka Nedeva*, Evgeni Genchev Agricultural University - Plovdiv, Bulgaria, Trakia University - Stara Zagora ABSTRACT Keywords: This study investigates the relationship between the development of the air transport and Economic Growth, Air the economic development of the Bulgarian regions and the improvement of its Transport, Competitive competitiveness over the period of 2000–2016. The timeliness of the problem is related Advantages, Region to the contradictory impact of the air transport on the economic effects of aviation development and related socio-economic effects at local and global level. The purpose of Received the report was to identify the impact of the air transport on the economic development of 19 May 2018 the region. In this connection, the following tasks have been set: to monitor trends in the Received in revised form development of the air passenger transport sector; to determine the impact of the average 20 October 2018 annual income per capita on the passenger flow; to establish the impact of passenger Accepted flows on the average annual income of the population as an indicator of the sustainable 23 October 2018 development of the region. The aim of the article was to establish the link between the passenger flow and the gross domestic product of the region. Economic data processing Correspondence: methods for the 10-year period were used through the Gretl program. The data obtained [email protected] is evidence of the positive impact of air transport development on the competitiveness of the region and its steady social-economic growth. -

2014 Fai World Championships for Space Models 2014 Fai Junior World Championships for Space Models

2014 FAI WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR SPACE MODELS 2014 FAI JUNIOR WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR SPACE MODELS These are th 20 World Space Modelling Championships for Seniors th 11 World Space Modelling Championships for Juniors th th 22 – 30 August, 2014 – Kaspichan, Bulgaria BULLETIN № 2 25 the March 2013 Kaspichan 2014 FAI WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS for SPACE MODELS 20th for SENIORS 11th for JUNIORS 22-30 august 2014 Kaspichan Bulgaria ORGANIZERS: By appointment of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) Organizers are: National Aero Club of Bulgaria Bulgarian Aeromodelling Federation Municipality of Kaspichan Space model Club “Modelist”, Kaspichan Director of the Championships: Mr. Stanev Plamen Sports Director: Mr. Ivanov Dimitar IT Service Manager: Mr. Yordanov Borislav Secretary of the Championships: Mrs. Stoyanova Sasha DESCRIPTION OF THE CHAMPIONSHIPS’ LOCATION: 2 Transportation: The World Championship shall be held in the municipality Kaspichan. Kaspichan is 20 km from the town of Shumen, where shall be registration and accommodation. Shumen is situated on the main road Sofia - Varna. Distance from Sofia to Shumen is 360 km, Varna - Shumen is 94 km and Varna - Ruse (125). The nearest international airports are in Varna (94 km), Burgas (155 km) and Sofia (360 km). Domestic flights: Flights to Sofia are served every day of the week at convenient hours. Flights are operated by the national carrier Bulgaria Air. On Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday the airline also operate combined package flights Sofia- Varna- Burgas. International flights: Austrian Airlines connects the Austrian capital Vienna to Varna every day of the week. The plane flies to Vienna at 13:30. WizzAir operates direct scheduled flights from Varna to London on Wednesday and Sunday. -

ACTION PLAN of the REPUBLIC of BULGARIA for CO2 EMISSIONS REDUCTION from CIVIL AVIATION (Edition July 2021)

ACTION PLAN OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA FOR CO2 EMISSIONS REDUCTION FROM CIVIL AVIATION (Edition July 2021) CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1. PREAMBLE II. CURRENT STATE OF AVIATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 1. CURRENT STATE OF AVIATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2. NATIONAL ACTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA III. EUROPEAN STATES’ ACTION PLANS - ECAC/EU COMMON SECTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. ECAC Baseline Scenario and estimated benefits of implemented measures B. Actions taken collectively in Europe 1. TECHNOLOGY AND STANDARDS 1.1. Aircraft emissions standards 1.2. Research and development: Clean Sky and the European Partnership for Clean Aviation 2. SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS (SAF) 2.1. ReFuelEU Aviation Initiative 2.2. Addressing barriers of SAF penetration into the market 2.3. Standards and requirements for SAF use 2.4. Research and development projects 3. OPERATIONAL IMPROVEMENTS 3.1. The EU's Single European Sky Initiative and SESAR 4. MARKET-BASED MEASURES 4.1. The EU Emissions Trading System and its linkages with other systems (Swiss ETS and UK ETS) 4.2. The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation 5. ADDITIONAL MEASURES 5.1. ACI Airport Carbon Accreditation 5.2. European industry roadmap to a net zero European aviation: Destination 2050 5.3. Environmental Label Programme 5.4. Multilateral capacity building projects 5.5. Green Airports research and innovation projects 6. SUPPLEMENTAL BENEFITS FOR DOMESTIC SECTORS APPENDIX A- Detailed results for ECAC Scenarios from Section A APPENDIX B- Note on the methods to -

Fraport Traffic Figures – April 2012: FRA's Upward

ANR 17/2012 – May 11, 2012 Fraport Traffic Figures – April 2012: FRA’s Upward Trend in Passenger Traffic Continues FRA/rap> Fraport AG welcomed about 4.8 million passengers at its Frankfurt Airport (FRA) home base in April 2012 – up 2.8 percent year-on-year. The reporting month even surpassed the previous April peak figure set in 2011 by some 130,000 passengers – despite the fact that this year’s Easter break occurred earlier and shifted holiday traffic into March 2012. Aircraft movements at Frankfurt declined due to the nighttime flight curfew (from 23:00 to 05:00) as well as the shorter Easter vacation period in April 2012. Thus, FRA registered 40,149 takeoffs and landings in April 2012, down 0.5 percent year-on-year. Airfreight decreased by 10.5 percent to 167,739 metric tons, while accumulated maximum takeoff weights (MTOWs) dropped by 1.6 percent to approximately 2.4 million metric tons. From January to April 2012, almost 17 million travelers used the FRA global hub. This represents a three percent jump compared to the same four month period last year. During this period, airfreight tonnage fell by 11.8 to 644,516 metric tons. Aircraft movements from January to April 2012 declined by 1.4 percent to 152,597 takeoffs and landings – due to strike-related flight cancellations and the nighttime ban at FRA. .…/2 Page 2 of 2: Fraport’s five majority-owned airports around the world served a total of 7.3 million passengers in the reporting month – growing by 1.7 percent year-on-year. -

BULGARIA LOCAL SINGLE SKY IMPLEMENTATION Level2019 1 - Implementation Overview

EUROCONTROL LSSIP 2019 - BULGARIA LOCAL SINGLE SKY IMPLEMENTATION Level2019 1 - Implementation Overview Document Title LSSIP Year 2019 for Bulgaria Info Centre Reference 20/01/15/07 Date of Edition 19/05/2020 LSSIP Focal Point Ivan ILIEV - [email protected] LSSIP Contact Person Ana Paula [email protected] EUROCONTROL/NMD/INF/PAS LSSIP Support Team [email protected] Status Released Intended for Agency Stakeholders Available in https://www.eurocontrol.int/service/local-single-sky- implementation-monitoring Reference Documents LSSIP Documents https://www.eurocontrol.int/service/local-single-sky- implementation-monitoring Master Plan Level 3 – Plan https://www.eurocontrol.int/publication/european-atm-master- Edition 2019 plan-implementation-plan-level-3-2019 Master Plan Level 3 – Report https://www.eurocontrol.int/publication/european-atm-master- Year 2019 plan-implementation-report-level-3-2019 European ATM Portal https://www.atmmasterplan.eu/ STATFOR Forecasts https://www.eurocontrol.int/statfor National AIP https://www.bulatsa.com/uslugi/aeronavigatsionna-informatsiya- ipublikatsiya FAB Performance Plan http://www.danubefab.eu/uploads/media/f59_danubefab_ rp2_performance_plan_body_and_annexes_signed.pdf LSSIP Year 2019 Bulgaria- Level 1 Released Issue TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... -

Report on Airports Used by Mahan Air Report to Congress

Report on Airports Used by Mahan Air Report to Congress February 15, 2019 Transportation Security Administration Message from the Administrator February 15, 2019 I am pleased to present the following “Report on Airports Used by Mahan Air,” prepared by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in consultation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and the Director of National Intelligence. This report was compiled pursuant to the TSA Modernization Act (P.L. 115-254), signed into law on October 5, 2018. The report provides information on Mahan Air operations and U.S. security interests at international Last Point of Departure airports. Pursuant to congressional requirements, this report is being provided to the following Members of Congress: The Honorable Roger Wicker Chairman, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation The Honorable Maria Cantwell Ranking Member, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation The Honorable Ron Johnson Chairman, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs The Honorable Gary Peters Ranking Member, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs The Honorable Bennie Thompson Chairman, House Committee on Homeland Security The Honorable Mike Rogers Ranking Member, House Committee on Homeland Security Inquiries relating to this report may be directed to me or the TSA Legislative Affairs office at (571) 227-2717. Sincerely yours, David P. Pekoske Administrator i Executive Summary On September 23, 2001, President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 13224, “Blocking Property and Prohibiting Transactions With Persons Who Commit, Threaten To Commit, or Support Terrorism.” The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Iranian airline Mahan Air as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist pursuant to Executive Order 13224 on October 12, 20111 for providing financial, military equipment, and technological support to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force.