2018 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAEM Syncope

IAEM Clinical Guideline Management of syncope in the emergency department Version 1 April, 2019 Authors: Dr Áine Mitchell, in collaboration with Dr Rosa McNamara, Professor Rose Anne Kenny and the IAEM Guideline Development Committee. DISCLAIMER IAEM recognises that patients, their situations, Emergency Departments and staff all vary. These guidelines cannot cover all clinical scenarios. The ultimate responsibility for the interpretation and application of these guidelines, the use of current information and a patient's overall care and wellbeing resides with the treating clinician. GLOSSARY OF TERMS AAA: Abdominal aortic aneurysm AFib: Atrial fibrillation ARVC: Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy AV: Atrioventricular βHCG: Beta human chorionic gonadotropin BP: Blood pressure BSL: Blood sugar level CCF: Congestive cardiac failure CM: Cardiomyopathy ECG: Electrocardiogram ED: Emergency Department EF: Ejection fraction ESC: European Society of Cardiology FHx: Family history GI: Gastrointestinal GP: General practitioner HCT: Haematocrit HOCM: Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Hx: History IAEM: Irish Association for Emergency Medicine ICD: Implanted cardioverter defibrillator IHD: Ischaemic heart disease MI: Myocardial Infarction OPD: Out-patient department PCM: Physical counter-pressure manoeuvres PE: Pulmonary embolus PMHx: Past Medical History PPM: Permanent pacemaker RSA: Road safety authority SAH: Sub-arachnoid haemorrhage SBP: Systolic blood pressure SCD: Sudden cardiac death SVT: Supra-ventricular tachycardia TIA: Transient ischaemic attack T-LOC: Transient loss of consciousness VT: Ventricular tachycardia WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White 2 IAEM CG: Management of syncope in the emergency department Version 1 April 2019 INTRODUCTION Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness (T-LOC) due to cerebral hypoperfusion. It is characterised by a rapid onset, short duration and spontaneous complete recovery. -

Supplement Ii to the Japanese Pharmacopoeia Fifteenth Edition

SUPPLEMENT II TO THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA FIFTEENTH EDITION Official From October 1, 2009 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the conven- ience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 425 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law (Law No. 145, 1960), we hereby revise a part of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 285, 2006) as follows*, and the revised Japanese Pharmacopoeia shall come into ef- fect on October 1, 2009. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as “previous Pharmacopoeia”) [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as “new Pharmacopoeia”)] and drugs which have been approved as of October 1, 2009 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as those ex- empted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Pharmaceu- tical Affairs Law (hereinafter referred to as “drugs exempted from approval”)], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on March 31, 2011. -

Clinical Presentation of Orthostatic Hypotension in the Elderly

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.70.827.638 on 1 September 1994. Downloaded from Postgrad Med J (1994) 70, 638 - 642 © The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1994 Medicine in the Elderly Clinical presentation oforthostatic hypotension in the elderly G.M. Craig Formerly Consultant Geriatrician, Northampton Health Authority, Northampton, UK Summary: Fifty cases of orthostatic hypotension in the elderly are analysed. Three main modes of presentation were identified: (1) falls or mobility problems; (2) mental confusion or dementia; or (3) predominantly cardiac symptoms. Selected case histories are given to illustrate diagnostic difficulties. Medication was responsible for orthostatic hypotension in 66% of patients and striking examples of polypharmacy were encountered. However, 34% of cases were not iatrogenic. Only 14% of patients had overtly postural symptoms. A high index ofsuspicion is needed to diagnose orthostatic hypotension in the elderly and the condition is often overlooked. The paper provides useful diagnostic clues for clinicians. Introduction Orthostatic hypotension is common in hospital reason the patients' age is not on record in ten The condition in cases. With this proviso the mean age was 80 years geriatric practice. may present by copyright. unusual ways in the elderly and can easily be (n = 40, range 63-97 years). There were 24 men overlooked. Some cases are a consequence of and 26 women in the series. autonomic failure. Physiological and pathology aspects, and treatment of autonomic failure are quite well covered in the literature.'I Detailed tests Clinical presentation have been devised to locate the precise level of neuronal dysfunction once the diagnosis has been The presenting features in order of frequency are established6 and the clinical features have been well shown in Table I. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

Evaluation and Management in an Urgent Care Setting

Syncope Evaluation and Management in an Urgent Care Setting Urgent message: When a patient presents to urgent care after a syncopal event, the clinician’s charge is to determine whether the episode was of benign or potentially life-threatening etiology and whether the patient should be transferred for further evaluation. Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, FACEP, FAAEM, Professor of Emergency Medicine, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Introduction yncope is a sudden, transient loss of consciousness with a loss of postural tone (typically, falling). It results from an abrupt, transient, and diffuse cerebral Smalfunction and is quickly followed by sponta- neous recovery. The term syncope excludes seizures, coma, shock, or other states of altered consciousness. Many patients will ascribe their syncopal episode to a sit- uationally mediated vasovagal episode. Despite this, the goals in the urgent care setting include the following: Ⅲ Determining whether the patient’s episode was actually a syncopal or presyncopal event, and if it could have a life-threatening etiology Ⅲ Stabilizing the patient Ⅲ Transferring those patients who need further diag- nostic studies or therapeutic interventions © John Bolesky, Artville © John Bolesky, Epidemiology Syncope accounts for up to 3% of emergency depart- common in young adults, while cardiac syncope ment (ED) visits and up to 6% of hospital admissions becomes increasingly more frequent with advancing each year in the United States.1,2 At some time in their age.4 The chance of having at least one syncopal episode lives, up to about half the population (12% to 48%) of in childhood is between 15% and 50%.5 Though a people may experience syncope.3 benign cause is usually found, syncope in children war- Syncope occurs in all age groups, but it is most com- rants prompt detailed evaluation.6 mon in adults. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,319,953 B1 Carlson Et Al

US006319953B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,319,953 B1 Carlson et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Nov. 20, 2001 (54) TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION AND WO 95/08549 3/1995 (W0). ANXIETY WITH FLUOXETINE AND AN WO 95/18124 7/1995 (W0). NK-1 RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST W0 96/05181 2/1996 (W0). W0 96/18643 6/1996 (W0). (75) Inventors: Emma Joanne Carlson, Puckeridge; W0 96/19233 6/1996 (W0). Nadia Melanie Rupniak, Bishops W0 96/24353 8/1996 (W0). W0 98/15277 4/1998 (W0). Stortford, both of (GB) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (73) Assignee: Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd., Hoddesdon (GB) Aguiar, M., et al., Physiology& Behavior, 1996, 60(4) 1183—1186. ( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Barden, N., et al., J. Neurochem., 1983, 41, 834—840. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 BristoW, L., et al., Eur J. Pharmacol., 1994, 253, 245—252. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Brodin, E., et al., Neuropharmacology, 1987, 26(6) 581—590. This patent is subject to a terminal dis Brodin, E., et al., Neuropeptides, 1994, 26, 253—260. claimer. Culman, J., et al., J. Physiol. Pharmacol., 1995, 73, 885—891. Cutler, et al., J. Psychopharmacol, 1994, 8, A22, 87. (21) Appl. N0.: 09/457,241 Elliott, P. J., Exp. Brain Res. UK, 1988, 73, 354—356. (22) Filed: Dec. 8, 1999 F—D—C Reports—Prescription Pharmaceuticals and Bio technology, Dec. 8, 1997, 59(49), 10. Related US. Application Data File, S. E., Pharm. Biochem. Behavior, 1997, 58, 3, 747—752. (60) Division of application No. -

Neurocardiogenic Syncope and Associated Conditions: Insight Into Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction

Türk Kardiyol Dern Arş - Arch Turk Soc Cardiol 2013;41(1):75-83 doi: 10.5543/tkda.2013.44420 75 Neurocardiogenic syncope and associated conditions: insight into autonomic nervous system dysfunction Nörokardiyojenik senkop ve ilişkili durumlar: Otonomik sinir sistemi işlev bozukluğuna bir bakış Antoine Kossaify, M.D., Kamal Kallab, M.D. Department of Syncope and Electrophysiology, ND Secours/USEK University Hospital, Byblos, Lebanon Summary– Neurocardiogenic syncope is known to be asso- Özet– Nörokardiyojenik senkopun mekanizması hala tam ola- ciated with autonomic nervous system dysfunction, although rak aydınlatılamamasına ragmen otonom sinir sistemi işlev the mechanism has not been entirely elucidated. In this study, bozukluğu ile ilişkili olduğu bilinmektedir. Bu yazıda nörokardi- we sought to highlight the pathogenic role of the autonomic yojenik senkop patogenezinde otonom sinir sisteminin rolünü nervous system in neurocardiogenic syncope and to review destekleyen en göze çarpıcı konuları araştırırken, temelinde the associated co-morbidities known to have a dysautonomic otonom sinir sistemi bozukluğunun olduğu bilinen komorbid basis. Herein we discuss migraine, orthostatic hypotension, durumları da gözden geçidik. Bu amaçla otonom sinir siste- postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, endothelial dys- minin patogenezdeki rolü ve klinik çıkarımları üzerine odak- function, chronic fatigue syndrome, and carotid sinus hyper- lanarak migren, ortostatik hipotansiyon, postüral ortostatik sensitivity with a focus on the pathogenic role of the autonom- taşikardi sendromu, endotel işlev bozukluğu, kronik yorgunluk ic nervous system and any consecutive clinical implications. sendromu ve karotis sinüs hipersensitivitesi tartışıldı. Tilt testi Other conditions, such as pre-syncopal heart rate acceleration sırasında ortaya çıkabilen senkop öncesi kalp atımlarında hız- and/or instability and pre-syncopal breathing instability, which lanma ve/veya instabilite ve senkop öncesi instabil solunum occur during a tilt test, are discussed in the same perspective. -

CAS Number Index

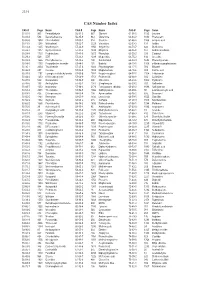

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Transdermal Drug Delivery Device Including An

(19) TZZ_ZZ¥¥_T (11) EP 1 807 033 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61F 13/02 (2006.01) A61L 15/16 (2006.01) 20.07.2016 Bulletin 2016/29 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 05815555.7 PCT/US2005/035806 (22) Date of filing: 07.10.2005 (87) International publication number: WO 2006/044206 (27.04.2006 Gazette 2006/17) (54) TRANSDERMAL DRUG DELIVERY DEVICE INCLUDING AN OCCLUSIVE BACKING VORRICHTUNG ZUR TRANSDERMALEN VERABREICHUNG VON ARZNEIMITTELN EINSCHLIESSLICH EINER VERSTOPFUNGSSICHERUNG DISPOSITIF D’ADMINISTRATION TRANSDERMIQUE DE MEDICAMENTS AVEC COUCHE SUPPORT OCCLUSIVE (84) Designated Contracting States: • MANTELLE, Juan AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Miami, FL 33186 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • NGUYEN, Viet SK TR Miami, FL 33176 (US) (30) Priority: 08.10.2004 US 616861 P (74) Representative: Awapatent AB P.O. Box 5117 (43) Date of publication of application: 200 71 Malmö (SE) 18.07.2007 Bulletin 2007/29 (56) References cited: (73) Proprietor: NOVEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. WO-A-02/36103 WO-A-97/23205 Miami, FL 33186 (US) WO-A-2005/046600 WO-A-2006/028863 US-A- 4 994 278 US-A- 4 994 278 (72) Inventors: US-A- 5 246 705 US-A- 5 474 783 • KANIOS, David US-A- 5 474 783 US-A1- 2001 051 180 Miami, FL 33196 (US) US-A1- 2002 128 345 US-A1- 2006 034 905 Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Syncope in Adults: Systematic Review and Proposal of a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Algorithm

International Journal of Cardiology 162 (2013) 149–157 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect International Journal of Cardiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijcard Review Syncope in adults: Systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm Salvatore Rosanio a,⁎, Ernst R. Schwarz b, David L. Ware c, Antonio Vitarelli d a University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology 855 Montgomery Street 76107 Fort Worth, TX, United States b Cardiology Division, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States c Cardiology Division, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, United States d Cardio-Respiratory Department, La Sapienza University, Rome, Italy article info abstract Article history: This review aims to provide a practical and up-to-date description on the relevance and classification of syncope Received 19 June 2011 in adults as well as a guidance on the optimal evaluation, management and treatment of this very common clin- Received in revised form 28 October 2011 ical and socioeconomic medical problem. We have summarized recent active research and emphasized the value Accepted 24 November 2011 for physicians to adhere current guidelines. A modern management of syncope should take into account 1) use of Available online 20 December 2011 risk stratification algorithms and implementation of syncope management units to increase the diagnostic yield and reduce costs; 2) early implantable loop recorders rather than late in the evaluation of unexplained syncope; Keywords: fi Syncope and 3) isometric physical counter-pressure maneuvers as rst-line treatment for patients with neurally- Pacing mediated reflex syncope and prodromal symptoms. -

STARS Reflex Syncope (VVS) Booklet.Indd

Reflex Syncope (Vasovagal Syncope) Working together with individuals, families and medical professionals to off er support and information on syncope and refl ex anoxic seizures www.stars.org.ukRegistered Charity No. 1084898 Registered Charity No. 1084898 Glossary of terms Refl ex syncope Refl ex syncope is a transient condition resulting from intermittent dysfunction of the autonomic nervous Contents system, which regulates blood pressure and heart rate. 12-lead ECG What is refl ex 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to record heart syncope? rhythms whilst in hospital. Heart rhythm monitor What are the Heart rhythm monitors are used to record heart rhythms symptoms? for up to a week whilst away from hospital. ILR How do I obtain a Implantable loop recorder (ILR) is a small thin device diagnosis? inserted under the skin to record heart rhythms. The device can remain in place for up to three years. What should I do if I Tilt table test feel dizzy or faint? A tilt table test is an autonomic test used to induce an attack whilst connected to heart and blood pressure What should my monitors. friends/family do Collapse if I faint? Abrupt loss of postural control Blackout/T-LoC What can I do to Transient loss of consciousness without neurological prevent syncope defi cit attacks? Syncope T-LoC due to transient global impairment of cerebral Are there any other perfusion treatments? Epilepsy Repeated episodes of excessive asynchronous discharge Driving and refl ex of cortical neurones leading to a clinical event syncope Psychogenic blackouts A cause of apparent blackouts without evidence of Flying and refl ex syncope or epilepsy syncope Fall Patient goes down freely under the infl uence of gravity Misdiagnosis TIA TIA (transient ischaemic attack) is caused by a temporary disruption in the blood supply to part of the brain (also known as a mini stroke) 2 What is reflex syncope? SYNCOPE (sin-co-pee) is a medical term for a This booklet is blackout caused by a sudden lack of blood supply designed for to the brain. -

Reflex Syncope in Children and Adolescents, Its Tclinical Characteristics and Syndromes, the Approach to Diagnosis, and Finally Treatment

Congenital heart disease REFLEX SYNCOPE IN CHILDREN AND Heart: first published as 10.1136/hrt.2003.022996 on 13 August 2004. Downloaded from ADOLESCENTS 1094 Wouter Wieling, Karin S Ganzeboom, J Philip Saul Heart 2004;90:1094–1100. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.022996 his article will address the epidemiology of reflex syncope in children and adolescents, its Tclinical characteristics and syndromes, the approach to diagnosis, and finally treatment. c EPIDEMIOLOGY Syncope can be defined as a temporary loss of consciousness and postural tone secondary to a lack of adequate cerebral blood perfusion. The incidence of syncope coming to medical attention appears to be clearly increased in two age groups—that is, in the young and in the old (fig 1).1 An incidence peak occurs around the age of 15 years, with females having more than twice the incidence of males.12 Syncope is an infrequent occurrence in adults. The incidence of syncope progressively increases over the age of about 40 years to become high in the older age groups. A lower peak occurs in older infants and toddlers, most commonly referred to as ‘‘breath-holding spells’’.3 The incidence of syncope in young subjects coming to medical attention varies from approximately 0.5 to 3 cases per 1000 (0.05–0.3%).2 Syncopal events which do not reach medical attention occur much more frequently. In fact, the recently published results of a survey of students averaging 20 years of age demonstrated that about 20% of males and 50% of females report to have experienced at least one syncopal episode.4 By comparison, the prevalence of seizures in a similar age group is about 5 per 1000 (0.5%)5 and cardiac syncope (that is, cardiac arrhythmias or structural heart disease) is even far less common.