Last Man Standing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warren Consolidated Schools Middle School Visual and Performing Arts

11 Time GM “Mark of Excellence” Award Winner Family Owned & Operated Since 1956 www.school.wcskids.net/wcspa Winterfest is a celebration of dance, musical In 1926, radium was a miracle cure, Madame Curie an theatre and the young performing artists of WCSPA. international celebrity, and luminous watches the latest rage—until the girls who painted them began to fall ill Winterfest is almost completely conceptualized with a mysterious disease. Inspired by a true story, and produced by students, allowing them to work Radium Girls traces the courageous efforts of Grace from vision to creation in the most authentic way. Fryer, a dial painter, as she fights for her day in court. Since this production is driven by student concepts and artistic choices, Called a “powerful” and “engrossing” drama by critics, it often has a broad range of styles, from the most contemporary hip- Radium Girls offers a wry, unflinching look at the hop and beat-boy moves to more lyrical and modern forms. Several peculiarly American obsessions with health, wealth, and pieces are also choreographed by staff and guest choreographers, the commercialization of science. This ensemble piece which often include tap, jazz, modern, ballroom, Broadway and of theatre explores a range of human emotions and will musical theatre style pieces. leave the audience questioning how events of this type continue to take place. “Incredibly entertaining!” Originally produced by Playwrights Theatre of New Jersey and developed with a commission “Amazingly talented dancers and superb choreography” grant from The Ensemble Studio Theatre/Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Science and Technology Project. Originally produced by Playwrights Theatre of New Jersey and developed with a “So much fun, I wanted to get up and join them on stage!” commission grant from The Ensemble Studio Theatre/Alfred P. -

KEVIN MAILLARD SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of LAW SYRACUSE, NY 13244 [email protected]

KEVIN MAILLARD SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW SYRACUSE, NY 13244 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Syracuse University College of Law Professor, 2012-Present; Assoc. Professor, 2010-2012; Asst. Professor, 2005-2010 Committees: Native American Law Student Association Faculty Advisor 2017- present; Black Law Student Association Faculty Advisor 2016-2017; Admissions and Diversity Committee 2010-Present: Faculty Appointments 2005-2006 Visiting Professorships Columbia Law School, Spring 2018 Hofstra Law School, 2009-2010 New York Law School, Spring 2009 Fordham Law School, Fall 2008 Hughes Hubbard & Reed, LLP, New York, NY Summer Associate, 2004-2005 EDUCATION University of Michigan, M.A., Ph.D. Political Theory, (2004) Ford Foundation Dissertation Fellowship, 2003-2004 Rackham Merit Fellowship, 1996-2002 University of Pennsylvania Law School, J.D, 2002 Symposium Editor, Journal of Constitutional Law, 2001-2002 Seminole Nation of Oklahoma Higher Education Award, 1999-2000 Equal Justice Foundation Award, Penn Law, 2002, 2001 Duke University, B.A., Public Policy, 1994 Seminole Nation of Oklahoma College Award, 1993 Jack Neely Scholarship, 1991 PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES The New York Times, Contributing Editor, Opinion, Arts, 2014-present The Atlantic, Contributor, 2015-present Amer. Assoc. of Law Schools (AALS) Minority Section Executive Board, 2017-Present Kaplan/PMBR Bar Lecturer, 2008-Present Indigenous Nations and Peoples Law, SSRN, Co-editor, 2006-2014 Alternatives to Marriage Project, Board Member 2009-2012 LatCrit, Planning Committee, 2008-2010 Association for Law, Culture, and Humanities, Board Member 2007-2009 Cooney Colloquium for Law and Humanities, Director 2006-2008 PUBLICATIONS Books and Book Chapters Commentary, FEMINIST JUDGMENTS: REWRITTEN REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE (Cambridge Univ. Press, forthcoming) LOVING IN A "POST-RACIAL" WORLD: RETHINKING RACE, SEX AND MARRIAGE, Kevin Noble Maillard and Rose Cuizon Villazor, eds. -

National Geographic Society

MAKING A MAN | THE SCIENCE OF GENDER | GIRLS AT RISK SPECIAL ISSUE GENDER REVOLUTION ‘The best thing about being a girl is, now I don’t have to pretend to be a boy.’ JANUARY 2017 I CONTENTS JANUARY 2017 • VOL. 231 • NO. 1 • OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY THE GENDER ISSUE Can science help us navigate the shifting land- scape of gender identity? 0DQG\ EHORZ LGHQWLƃHV as IDşDIDƃQH a third gender in Samoa. 48 RETHINKING GENDER %\5RELQ0DUDQW]+HQLJ 3KRWRJUDSKVE\/\QQ-RKQVRQ | CONTENTS ELSEWHERE 30 | I AM NINE YEARS OLD 74 | MAKING A MAN TELEVISION GENDER REVOLUTION: 1DWLRQDO*HRJUDSKLF traveled to 80 In traditional cultures the path to man- A JOURNEY WITH homes on four continents to ask kids hood is marked with ceremonial rites of KATIE COURIC KRZJHQGHUDƂHFWVWKHLUOLYHV7KH passage. But in societies moving away answers from this diverse group of from strict gender roles, boys have to A look children were astute and revealing. ƃQGWKHLURZQZD\VWREHFRPHPHQ at how %\(YH&RQDQW %\&KLS%URZQ genetics, 3KRWRJUDSKVE\5RELQ+DPPRQG 3KRWRJUDSKVE\3HWH0XOOHU culture, and brain chemistry shape gender. February 6 at 8/7c on National Geographic. TELEVISION JOIN THE SAFARI Watch live as guides track Africa’s iconic animals on 6DIDUL/LYH a series premiering January 1 at 10/9c on Nat Geo WILD. 110 | AMERICAN GIRL 130 | DANGEROUS LIVES OF GIRLS The guides also will take In some ways it’s easier to be an Amer- In Sierra Leone, wracked by civil war and viewers’ questions via ican girl these days: Although beauty Ebola, nearly half of girls marry before Twitter at #SafariLive. -

Friendsof Acadia

FRIENDS OF ACADIA 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2013 BOARD OF DIRECTORS HONORARY TRUSTEES David Rockefeller Diana R. McDowell Hilary Krieger Edward L. Samek, Chair Eleanor Ames Jeannine Ross Director of Finance and Environmental Compliance and Administration Recreation Management Intern John Fassak, Vice Chair Robert and Anne Bass Howard Solomon Mike Staggs Allison Kuzar Michael Cook, Treasurer Curtis and Patricia Blake Erwin Soule Office Manager Ridge Runner Emily Beck, Secretary Robert and Sylvia Blake Diana Davis Spencer Geneva Langley Frederic A. Bourke Jr. Julia Merck Utsch SEASONAL STAFF Wild Gardens of Acadia Fred Benson Tristram and Ruth Colket Supervising Gardener EMERITUS TRUSTEES Anna Adams Brownie Carson Gail Cook Senior Field Crew Leader Moira O’Neill W. Kent Olson Ridge Runner Gail Clark Shelby and Gale Davis David Anderson Charles R. Tyson Jr. Hannah Sistare Clark Dianna Emory Acadia Youth Technology Noah Sawyer Team Intern Wild Gardens of Acadia Intern Andrew Davis Frances Fitzgerald FRIENDS OF ACADIA STAFF Kristin Dillon Abigail Seymour Nathaniel Fenton Sheldon Goldthwait Theresa Begley Ridge Runner Recreation Technician Chris Fogg Neva Goodwin Projects and Events Coordinator Benjamin Dunphey Kevin Tabb Jill Goldthwait Paul and Eileen Growald Mary Boëchat Field Crew Leader Acadia Youth Technology John* and Polly Guth Development Officer Team Leader C. Boyden Gray Jared Garfield Paul Haertel Liam Torrey Anne Green Sharon Broom Ridge Runner Lee Judd Development Officer Acadia Youth Technology Cookie Horner Ari Gillar-Leinwohl Debby Lash Aimee Beal Church Team Intern Jan Kärst Exotic Plant Management Courtney Wigdahl Linda Lewis Communications and Team Member Jack Kelley Aquatic Scientist Liz Martinez Outreach Coordinator Sara Greller Meredith Moriarty Tyler Wood Gerrish and Phoebe Milliken Stephanie Clement Acadia Youth Technology Lili Pew Conservation Director Team Evaluation Fellow Acadia Youth Technology George J. -

Virginia: Birthplace of America

VIRGINIA: BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA Over the past 400 years AMERICAN EVOLUTION™ has been rooted in Virginia. From the first permanent American settlement to its cultural diversity, and its commerce and industry, Virginia has long been recognized as the birthplace of our nation and has been influential in shaping our ideals of democracy, diversity and opportunity. • Virginia is home to numerous national historic sites including Jamestown, Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, Colonial Williamsburg, Arlington National Cemetery, Appomattox Court House, and Fort Monroe. • Some of America’s most prominent patriots, and eight U.S. Presidents, were Virginians – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. • Virginia produced explorers and innovators such as Lewis & Clark, pioneering physician Walter Reed, North Pole discoverer Richard Byrd, and Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, all whose genius and dedication transformed America. • Bristol, Virginia is recognized as the birthplace of country music. • Virginia musicians Maybelle Carter, June Carter Cash, Ella Fitzgerald, Patsy Cline, and the Statler Brothers helped write the American songbook, which today is interpreted by the current generation of Virginian musicians such as Bruce Hornsby, Pharrell Williams, and Missy Elliot. • Virginia is home to authors such as Willa Cather, Anne Spencer, Russell Baker, and Tom Wolfe, who captured distinctly American stories on paper. • Influential women who hail from the Commonwealth include Katie Couric, Sandra Bullock, Wanda Sykes, and Shirley MacLaine. • Athletes from Virginia – each who elevated the standards of their sport – include Pernell Whitaker, Moses Malone, Fran Tarkenton, Sam Snead, Wendell Scott, Arthur Ashe, Gabrielle Douglas, and Francena McCorory. -

John Franklin

John Franklin SAG-AFTRA, AEA ` FILM: (Sample) Hag Supporting Scaryopolis, Dir: Erik Gardner Children of the Corn “666” (Co-Writer) Starring Dimension, Dir: Kari Skogland Python Python Supporting U.F.O., Dir: Richard Clabaugh Wag the Dog Supporting Tribeca, Dir: Barry Levinson George B. (Sundance ‘97) Starring Tango West, Dir: Eric Lea Killing Grounds Supporting Indpt, Dir: Kurt Anderson Tammy & the Teenage T-Rex Starring Platinic Films, Dir: Stewart Raffill Addams Family Values (Cousin Itt) Supporting Paramount, Dir: Barry Sonnenfeld The Addams Family (Cousin Itt) Supporting Paramount, Dir: Barry Sonnenfeld A Night at the Magic Castle Starring Indpt, Dir: Icek Tenenbaum Children of the Corn Starring New World, Dir: Fritz Kiersch TELEVISION: (Sample) Fresh Off the Boat Guest Star ABC, Dir: Sean Kavanagh Brooklyn Nine-Nine Co-Star Universal TV, Dir: Luke Del Tredici Hell’s Kitty (Web Series) Guest Star Smart Media, Dir: Nicholas Tana Horrorfied (Pilot) Lead Wheatboyz Prodns. Dir: Jeff Seymore The Christmas Secret Lead CBS MOW, Dir: Ian Barry Star Trek: Voyager Star Trek: Voyager Co-Star UPN, Dir: Terry Windell All That All That Co-Star Nickelodeon, Dir: Terri McCoy Lee Evans Conquers America Recurring NBC Pilot, Dir: Robby Benson Tower Of Terror Lead Disney MOW, Dir: D.J. MacHale Chicago Hope Guest Star 20th Century Fox, Dir: Sandy Smolan Beauty & the Beast Guest Star CBS, Dir: Thomas J. Wright Highway to Heaven Guest Star MGM, Dir: Michael Landon Mighty Pawns Co-Star PBS, Dir: Eric Laneuville Kids, Incorporated (2 Episodes) Guest Star -

Inside • Academe Vol

Inside • Academe Vol. XIII • No. 3-4 • 2007–2008 A publication of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni In This Issue… Bradley Project Puts Focus on American Identity 2 In Box Pluribus Unum—from many, one. teractive, where more than 60 percent Th at is the name of a compelling of Americans surveyed believe that our ATHENA Preview E new report issued by the Bradley Proj- national identity is getting weaker. More 3 Georgia Launches ect on America’s National Identity that troubling, younger Americans are less Study of Campus fi nds America is facing an identity crisis. likely than older Americans to believe in Climate Funded by the a unique national 4 NEA Calls for Action Lynde and Harry identity or even a on Reading Bradley Foundation unique American To Require or Not to and coordinated by culture. Require History ACTA, the report Over 200,000 focuses on issues E PLURIBUS UNUM visitors have al- 5 Hawaii Regent Urges central to ACTA’s ready visited the Trustee Engagement mission—civic project website and 6 Heard on Campus education and the commentary has 7 Professor Kagan to teaching of Ameri- been widespread. to Receive Merrill can history—and ACTA friend Award calls for a national THE BRADLEY PROJECT ON David McCullough conversation on AMERICA’S NATIONAL IDENTITY endorsed the report 8 New Guide Helps these topics. Citing calling it “the clear- Trustees a number of ACTA est, most powerful Meet ACTA’s Interns studies, the report summons yet, to 9 George Washington, fi nds that American all of us, to restore Education, and the identity is weakening and that America the American story to its rightful, vital Next Generation is in danger of becoming “from one, place in American life and in how we Change at ACTA many.” Underscoring this conclusion are educate our children.” And at the Na- sobering results of a new national poll, tional Press Club event announcing the 10 Alexander Hamilton conducted for the Project by HarrisIn- report, James C. -

Annual Report 2017

IDEAS LEADERSHIP ACTION OUR MISSION 2 Letter from Dan Porterfield, President and CEO WHAT WE DO 6 Policy Programs 16 Leadership Initiatives 20 Public Programs 26 Youth & Engagement Programs 30 Seminars 34 International Partnerships 38 Media Resources THE YEAR IN REVIEW 40 2017-2018 Selected Highlights of the Institute's Work 42 Live on the Aspen Stage INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT 46 Capital Campaigns 48 The Paepcke Society 48 The Heritage Society 50 Society of Fellows 51 Wye Fellows 52 Justice Circle and Arts Circle 55 Philanthropic Partners 56 Supporters STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 90 2017 Annual Report WHO WE ARE 96 Our Locations 98 Aspen Institute Leadership 104 Board of Trustees LETTER FROM DAN PORTERFIELD, PRESIDENT AND CEO A LETTER FROM PRESIDENT AND CEO DAN PORTERFIELD There is nothing quite like the Aspen Institute. It is In the years to come, the Aspen Institute will deepen an extraordinary—and unique—American institution. our impacts. It is crucial that we enhance the devel- We work between fields and across divides as a opment of the young, address the urgent challenges non-profit force for good whose mission is to con- of the future, and renew the ideals of democratic so- vene change-makers of every type, established and ciety. I look forward to working closely with our many emerging, to frame and then solve society’s most partners and friends as we write the next chapter on important problems. We lead on almost every issue the Institute’s scope and leadership for America and with a tool kit stocked for solution-building—always the world. -

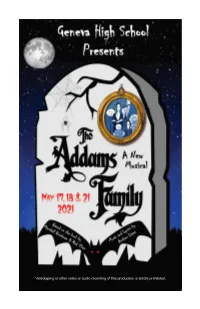

The Addams Family

DLO DINNER THEATRE PRODUCTION 2017 AUDITIONS FOR VIOLET Sun., Nov. 13, 2 p.m.,Tues., Nov. 15, 6 p.m. Callbacks (if needed) Wed., Nov. 16, TBA “It’s about the journey you take to discover who you are.” PERFORMANCES: Feb. 17-19, 2017 FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT AUDITIONS: All details are not set at this time. Watch for further information on the DLO website and Facebook page as arrangements and plans are finalized. FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT VIOLET: CAST: 5 women and 6 men and a possibility of a small gospel choir. CHARACTERS: Character descriptions are available on the DLO website. THE STORY: This multiple award-winning musical follows a scarred woman who embarks on a cross-country bus trip to be healed by a minister, and discovers the true meaning of beauty along the way. As a girl, Violet was struck by a wayward axe blade when her father was chopping wood, leaving her with a visible scar across her face. With enough money finally saved she’s traveling across the 1964 Deep South towards a miracle: the healing touch of a TV evangelist that will make her beautiful. Along the way, she befriends two young soldiers – one white, one African-American – friendships that could grow into something more. Will Violet find the healing she seeks? QUESTIONS?: Contact director, Jeanne Dunn, at [email protected] RATINGS: DLO has given Violet a PG-13 rating for language, mature themes and adult situations in the story. Director’s Note In Loving Memory of MYRTLE YOUNG CLIFTON “The unknown may be frightening, the darkness overwhelming, but 1927–2016 if we don’t run from it, we may see our mysterious, miraculous lives a major force in founding DLO finally illuminated. -

Playbill Possible and Have Been Enhancing Our Theatre Program with Other “Extras” for Many Years Now

Marshall Brickman & Rick Elice Based on the book by Music and Lyrics by Andrew Lippa GrahamsAd2020.pdf 1 9/8/20 9:30 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 302 S. 3rd St., Geneva, IL 318 S. 3rd St., Geneva, IL Phone: (630)232-6655 Phone: (630)845-3180 www.grahamschocolate.com www.318coffeehouse.com Families ~ Seniors ~ Headshots Book by MARSHALL BRICKMAN and RICK ELICE Music and Lyrics by ANDREW LIPPA Based on Characters Created by Charles Addams. Originally produced on Broadway by Stuart Oken, Roy Furman, Michael Leavitt, Five Cent Productions, Stephen Schuler, Decca Theatricals, Scott M. Delman, Stuart Ditsky, Terry Allen Kramer, Stephanie P. McClelland, James L. Nederlander, Eva Price, Jam Theatricals/Mary LuRoffe, Pittsburgh CLO/Gutterman-Swinsky, Vivek Tiwary/Gary Kaplan, The Weinstein Company/Clarence, LLC, Adam Zotovich/Tribe www.kimayarsphotography.com Theatricals; By Special Arrangement with Elephant Eye Theatrical. THE ADDAMS FAMILY A NEW MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with and [email protected] all authorized performance materials are supplied by Theatrical Rights Worldwide 1180 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 640, New York, NY 10036. www.theatricalrights.com Geneva Community High School 416 McKinley Avenue Phone: (630) 463-3800 Geneva, Illinois 60134 Fax: (630) 463-3809 Dear Friends of Geneva’s Theatre Productions: Welcome to Geneva Community High School’s performance of The Addams Family - A New Musical. Our cast, crew, and directors have devoted themselves to the creation of this production, and they’ve had a lot of fun doing it. Their commitment to our drama and music programs underscores the rich tradition of excellence and success in our performing arts endeavors. -

Sherlock Holmes Films

Checklist of Sherlock Holmes (and Holmes related) Films and Television Programs CATEGORY Sherlock Holmes has been a popular character from the earliest days of motion pictures. Writers and producers realized Canonical story (Based on one of the original 56 s that use of a deerstalker and magnifying lens was an easily recognized indication of a detective character. This has led to stories or 4 novels) many presentations of a comedic detective with Sherlockian mannerisms or props. Many writers have also had an Pastiche (Serious storyline but not canonical) p established character in a series use Holmes’s icons (the deerstalker and lens) in order to convey the fact that they are acting like a detective. Derivative (Based on someone from the original d Added since 1-25-2016 tales or a descendant) The listing has been split into subcategories to indicate the various cinema and television presentations of Holmes either Associated (Someone imitating Holmes or a a in straightforward stories or pastiches; as portrayals of someone with Holmes-like characteristics; or as parody or noncanonical character who has Holmes's comedic depictions. Almost all of the animation presentations are parodies or of characters with Holmes-like mannerisms during the episode) mannerisms and so that section has not been split into different subcategories. For further information see "Notes" at the Comedy/parody c end of the list. Not classified - Title Date Country Holmes Watson Production Co. Alternate titles and Notes Source(s) Page Movie Films - Serious Portrayals (Canonical and Pastiches) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes 1905 * USA Gilbert M. Anderson ? --- The Vitagraph Co. -

An Old Woman Bumped Her on Canal

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-13-2016 An Old Woman Bumped Her on Canal Nordette N. Adams University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Nordette N., "An Old Woman Bumped Her on Canal" (2016). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2210. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2210 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Old Woman Bumped Her on Canal A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Poetry By Nordette N. Adams B.A. Augusta State University, 1996 May 2016 © 2016 Nordette N. Adams ii Dedication In memory of my parents, Fannie Naomi Reddix Adams (1927-2007) and Norwood Edward Adams (1920-2012), also my brother Benjamin James Adams (1967-2012).