Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

2018/2020 Undergraduate Bulletin

FISK 2018/2020 Undergraduate Bulletin 1 Cover image: Cravath Hall, named for Fisk’s first president (1875-1900) photo: photographer unknown 2 About the Bulletin Inquiries concerning normal operations of the The content of this Bulletin represents the most current institution such as admission requirements, financial aid, information available at the time of publication. As Fisk educational programs, etc., should be addressed directly to University continues to provide the highest quality of the appropriate office at Fisk University. The Commission intellectual and leadership development opportunities, the on Colleges is to be contacted only if there is evidence that curriculum is always expanding to meet the changes in appears to support an institution’s significant non- graduate and professional training as well as the changing compliance with a requirement or standard. demands of the global workforce. New opportunities will Even before regional accreditation was available to arise and, subsequently, modifications may be made to African-American institutions, Fisk had gained recognition existing programs and to the information contained in this by leading universities throughout the nation and by such Bulletin without prior notice. Thus, while the provisions of agencies as the Board of Regents of the State of New this Bulletin will be applied as stated, Fisk University York, thereby enabling Fisk graduates' acceptance into retains the right to change the policies and programs graduate and professional schools. In 1930, Fisk became contained herein at its discretion. The Bulletin is not an the first African-American institution to gain accreditation irrevocable contract between Fisk University and a student. by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. -

EOD Will Provide the Funds to Transport Students to the Concerts Free of Charge

MEDIA CONTACTS: Sarah Wertheimer . 941-404-5710 . [email protected] Su Byron . 941-955-8103 . [email protected] To interview artists, email your request to [email protected]. Nationally Acclaimed Anti-Bullying Music Tour Returns to Area Schools November 9-13 Young artists from "X-Factor,” "The Voice," and “American Idol” will perform at eight free concerts for over 6,700 students from Sarasota and Manatee counties. (Sarasota, FL) The Sarasota-based Embracing Our Differences has partnered again with the Allstar Nation Tour (ANT) to bring eight free concert assemblies for students from 12 schools in Sarasota and Manatee counties, November 9-13. The Allstar Nation Tour delivers powerful, anti-bullying messages to students across the nation through concert assemblies that feature popular musical artists. Some of the artists have appeared on such top entertainment shows as The Voice, X-Factor and American Idol. Between songs, performers speak out against bullying, share personal experiences, and discuss prevention methods. Former X-Factor Top 6 finalist Drew Ryniewicz, American Idol finalist Robbie Rosen, Indie Music Channel’s “Best New Teen Artist” winner Lauren Carnahan, and The Voice contestant Branden Mendoza, with his band My Only Escape, are the artists scheduled to perform eight concerts in North Port, Osprey and Sarasota for over 6,700 students from Booker Middle School, Booker High School, Gulf Gate Elementary, North Port High School, Phillippi Shores Elementary, Pine View School, Riverview High School and Wilkinson Elementary in Sarasota, Lincoln Middle School in Palmetto, and Team Success School and State College of Florida Collegiate School in Bradenton. The concerts will be held at the performing arts complexes at North Port High School, 6400 West Price Blvd., North Port; Booker Middle School, 2250 Myrtle Street, Sarasota; Booker High School, 3201 N. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

The Hits Keep Coming: Pop Music and Violent Relationships

Chapter 4: Teen Dating and Relationships | Exercise 7 Abuse Abuse Aggressive Control Perpetrator THE HITS KEEP Popular culture Power Social Norms Victim Violence COMING Domestic Violence Act POP MUSIC AND VIOLENT RELATIONSHIPS 1. To help learners recognise the role that popular culture plays in our 45 minutes ideas about relationships. Worksheet: ‘The Hits Keep Coming’ 2. For learners to identify messages in lyrics as relating to healthy (provided) (equal) or unhealthy (unequal/controlling) relationships. Teacher Answer Key 3. For learners to consider how their own attitudes about ideal Teen Power and Control Wheel relationships and dating behaviour are influenced by pop music. Teen Equality Wheel e. What do you think are the effects when men and women get these PROCEDURE messages from so many different sources all the time? Introduce the exercise by telling learners that they are going to analyse lyrics from popular songs in order to identify what these songs tell us about relationships. You should include the following: • They think this is normal, and the way relationships should Provide each learner with a copy of the Worksheet: ‘The Hits Keep be Coming’ and copies of both the ‘Teen Equality Wheel’ and ‘Teen Power • They cannot tell if they are in unhealthy relationships and Control Wheel’. You could also put an enlarged copy of each wheel because they have no healthy role models. on the board where all learners can see them. • Women expect to be treated poorly Explain that learners should read the lyrics carefully and then fill out the • Men expect that they should be dominant or aggressive which segment of either wheel (Teen Power or Teen Equality) that best • Relationships are less fulfilling because partners are not describes the lyric (column 2), and the reason that it fits this segment taught or modelled communication, respect and trust. -

Concert History of the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum

Historical Concert List updated December 9, 2020 Sorted by Artist Sorted by Chronological Order .38 Special 3/27/1981 Casting Crowns 9/29/2020 .38 Special 10/5/1986 Mitchell Tenpenny 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/17/1984 Jordan Davis 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/16/1982 Chris Janson 9/25/2020 3 Doors Down 7/9/2003 Newsboys United 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/6/2000 Mandisa 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/26/1999 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 4 Him 12/6/1996 Crowder 2/20/2020 5th Dimension 3/10/1972 Hillsong Young & Free 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 4/4/2001 Andy Mineo 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 10/24/1999 Building 429 2/20/2020 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 RED 2/20/2020 Aaron Carter 3/7/2002 Austin French 2/20/2020 Aaron Jeoffrey 8/13/1999 Newsong 2/20/2020 Aaron Tippin 5/5/1991 Riley Clemmons 2/20/2020 AC/DC 11/21/1990 Ballenger 2/20/2020 AC/DC 5/13/1988 Zauntee 2/20/2020 AC/DC 9/7/1986 KISS 2/16/2020 AC/DC 9/21/1980 David Lee Roth 2/16/2020 AC/DC 7/31/1979 Korn 2/4/2020 AC/DC 10/3/1978 Breaking Benjamin 2/4/2020 AC/DC 12/15/1977 Bones UK 2/4/2020 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 Five Finger Death Punch 12/9/2019 Addison Agen 2/8/2018 Three Days Grace 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 12/2/2002 Bad Wolves 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 11/23/1998 Fire From The Gods 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 5/17/1998 Chris Young 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 6/22/1993 Eli Young Band 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 5/29/1986 Matt Stell 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 10/3/1978 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 10/7/1977 I Prevail 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 5/25/1976 Beartooth 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 3/26/1975 Can't Swim 11/14/2019 After Seven 5/19/1991 Luke Bryan 10/23/2019 After The Fire -

American Spiritual Program Fall 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009 • 7:30 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church • 1401 Camden Avenue, Salisbury Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music influenced by the spiritual. This concert is sponsored by The Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund;SU President Janet Dudley-Eshbach; Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Diane Allen; Dean Maarten Pereboom, Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts; Dean Dennis Pataniczek, Samuel W. and Marilyn C. Seidel School of Education and Professional Studies; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council. THE AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM THE SPIRITUAL Walk Together, Children ..........................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Jacob’s Ladder ..........................................................................................................arr. Harry Robert Wilson Angelique Clay, Soprano Soloist Plenty Good Room ..................................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Go Down, Moses ............................................................................................................arr. Harry T. Burleigh Frederick Jackson, Bass-Baritone Is There Anybody Here? ....................................................................................................arr. -

Senior Oliver Haynes Publishes Ffrst Novel

The Vol. XCVIII. NO. 4 Get in the Halloween ou’wester spirit with spooky TV SOctober 24, 2012 e Fortnightly Student Newspaper of Rhodes College See Page 6 Senior Oliver Haynes publishes fi rst novel Tyler Springs Staff Writer photo courtesy of C. Slawson Chip Slawson Staff Writer In recognition of October being Domestic Violence Awareness Month, Sigma Nu sponsored a viewing of ‘Telling Amy’s Story,’ a documentary of one woman’s tragic struggle with an abuser. Shelby County Attorney General Amy Weirich delivered opening remarks. Following the viewing, Sigma Nu philanthropy chairman Kondwani Joe Banda moderated a panel discussion with Carol Casey; Marianne Luther; Oliette Murry-Drobot, director of the Memphis Family Safety Shelter; and Lia White-Roemer, a domestic violence survivor. Better Together: Promoting Religious Graphic courtesy of O. Haynes Oliver Haynes ’13 self-published his rst full-length novel, which debuted on Amazon.com Unity and Tolerance earlier this month. The artwork is his own. Julia Fawal To write and publish any book at an early age requires an immense amount time, discipline and energy. Co-News Editor F. Scott Fitzgerald dropped out of college and did a stint in the army before successfully revising and selling Fasting is a tradition shared by almost every major faith. It unites people of his fi rst novel at age 24. Michael Crichton managed to get his fi rst novel printed while he was still in medi- all religious affi liations and highlights that they are not as diff erent as it might cal school at age 27. seem. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

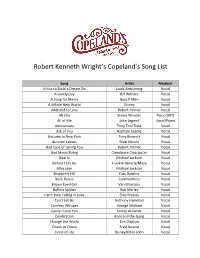

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

Party at the Limit Song List

Party At The Limit Song List Walking on Sunshine by Katina and the Waves Shook Me All Night Long by AC/DC Wagon Wheel by Darius Rucker Route 66 by Nat King Cole Rock Steady by The Whispers Play that Funky Music by Wild Cherry Humble and Kind by Tim McGraw Hole in the Wall by Mel Waiters Honey I’m Good by Andy Grammer Got My Whiskey by Mel Waiters Don’t Know Why by Norah Jones Brown Eyed Girl by Van Morrison Boogie Oogie Oogie by A Taste of Honey Bad Girls by Donna Summers Bang Bang by Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj, Jessie J At Last by Etta James Anniversary by Tone, Toni, Tony All I Do is Win by DJ Khaled Bad Boys for Life Intro EWF Intro Lose Yourself Intro Blame it by Jamie Foxx Cake by the Ocean by DNCE Can’t Feel My Face by The Weekend Get Right Back to My Baby by Vivian Green Free Falling by Tom Petty Footsteps in the Dark by Isley Brothers Hey Ya by Andre 3000 Hotline Bling by Drake Just the Two of Us by Bill Withers Isn’t She Lovely by Stevie Wonder Ribbon in the Sky by Stevie Wonder Natural Woman by Aretha Franklin Livin La Vida Loca by Rickey Martin Love on Top by Beyonce Ordinary People by John Legend On and On by Erykah Badu Please Don’t Stop the Music by Rihanna Real Love by Mary J Blige Just Fine by Mary J Blige Crazy in Love by Beyonce De Ja Vu by Beyonce Stand by Me by Ben E King Staying Alive by the Bee Gees Stay With Me by Sam Smith All of Me by John Legend Starboy by The Weekend Smooth Operator by Sade To Be Real- Chaka Khan Sweet Love by Anita Baker Chicken Fried by Zac Brown Band I Got a Feeling by Black Eyed Peas OMG -

1865-1962. Mary E. Spence Papers, 1853-1950

SPENCE, MARY E. (MARY ELIZABETH), 1865-1962. Mary E. Spence papers, 1853-1950 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Spence, Mary E. (Mary Elizabeth), 1865-1962. Title: Mary E. Spence papers, 1853-1950 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 811 Extent: 1 linear foot (2 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP) Abstract: Papers of educator Mary E. Spence and her father, Adam Knight Spence Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Spence family papers, Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee and Adam Knight Spence and John Wesley Work collection, Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African- American Culture and History, Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System, Atlanta, Georgia. Source Purchase, 1997. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Mary E. Spence papers, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Susan Potts McDonald and Vicky Hesford, December 1998. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Mary E. Spence papers, 1853-1950 Manuscript Collection No. 811 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other oppressive language.