A Shakespeare Miscellany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

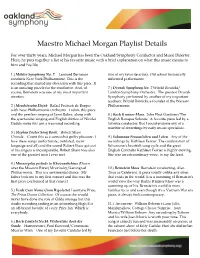

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Lauryna Bendžiūnaitė Soprano

LAURYNA BENDŽIŪNAITĖ SOPRANO BIOGRAPHY LONG VERSION Lauryna Bendžiūnaitė is a Lithuanian soprano who was a member of the ensemble of Staatstheater Stuttgart from 2014 - 2018. Her roles in Stuttgart have included Musetta, Ännchen, Zerlina, Susanna and Karolka. She also sang Dalinda in Handel’s Ariodante, appeared in Bieito’s new production of Purcell’s Fairy Queen conducted by Curnyn, as well as, in die Dirne Boesmans’s Reigen. Last season she performed Susanna at the Opera National du Rhin where she will return to sing Despina in Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte. Ms. Bendžiūnaitė studied at the Royal Academy of Music, London with Joy Mammen, winning the Pavarotti prize before moving on to further studies with Dennis O’Neil and Kiri te Kanawa. Prior to attending the Royal Academy, Ms. Bendžiūnaitė had studied with professor R. Maciutė at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre gaining the first prize in the International XXI Century Art Contest (Ukraine). She has since been a member of the Vilnius City Opera where her roles have included Pamina, Despina, Musetta, Sophie (Werther) and Johanna (Sweeney Todd). With the Lithuanian National Opera she sang Xenia (Boris Godunov). In 2012 Ms. Bendžiūnaitė sang Musetta at the Royal Swedish Opera where she was invited to repeat the role in 2013. In concert Ms. Bendžiūnaitė has performed with the Lithuanian National Philharmonic Orchestra regularly performs with the State Symphony Orchestra and the National Chamber Orchestra. She appeared in gala concerts with Kiri Te Kanawa in London and Dublin. She toured with the Kammerorchester Basel conducted by Trevor Pinnock with music from Purcell’s Fairy Queen and Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Nights Dream, which she also sang at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo in 2017. -

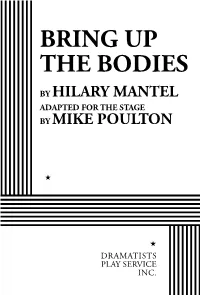

Bring up the Bodies

BRING UP THE BODIES BY HILARY MANTEL ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY MIKE POULTON DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. BRING UP THE BODIES Copyright © 2016, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Copyright © 2014, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Bring Up the Bodies Copyright © 2012, Tertius Enterprises Ltd All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BRING UP THE BODIES is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BRING UP THE BODIES are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

Czech Philharmonic

Biography Czech Philharmonic “The Czech Philharmonic is among the very few orchestras that have managed to preserve a unique identity. In a music world that is increasingly globalized and uniform, the Orchestra’s noble tradition has retained authenticity of expression and sound, making it one of the world's artistic treasures. When the orchestra and Czech government asked me to succeed beloved Jiří Bělohlávek, I felt deeply honoured by the trust they were ready to place in me. There is no greater privilege for an artist than to become part of and lead an institution that shares the same values, the same commitment and the same devotion to the art of music.” Semyon Bychkov, Chief Conductor & Music Director The 125 year-old Czech Philharmonic gave its first concert – an all Dvořák programme which included the world première of his Biblical Songs, Nos. 1-5 conducted by the composer himself - in the famed Rudolfinum Hall on 4 January 1896. Acknowledged for its definitive interpretations of Czech composers, whose music the Czech Philharmonic has championed since its formation, the Orchestra is also recognised for the special relationship it has to the music of Brahms and Tchaikovsky - friends of Dvořák - and to Mahler, who gave the world première of his Symphony No. 7 with the Orchestra in 1908. The Czech Philharmonic’s extraordinary and proud history reflects both its location at the very heart of Europe and the Czech Republic’s turbulent political history, for which Smetana’s Má vlast (My Homeland) has become a potent symbol. The Orchestra gave its first full rendition of Má vlast in a brewery in Smíchov in 1901; in 1925 under Chief Conductor Václav Talich, Má vlast was the Orchestra’s first live broadcast and, five years later, the first work that the Orchestra committed to disc. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Anna Bolena Opera by Gaetano Donizetti

ANNA BOLENA OPERA BY GAETANO DONIZETTI Presentation by George Kurti Plohn Anna Bolena, an opera in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, is recounting the tragedy of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of England's King Henry VIII. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style, meaning beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, prevalent during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was born in 1797 and died in 1848, at only 51 years of age, of syphilis for which he was institutionalized at the end of his life. Over the course of is short career, Donizetti was able to compose 70 operas. Anna Bolena is the second of four operas by Donizetti dealing with the Tudor period in English history, followed by Maria Stuarda (named for Mary, Queen of Scots), and Roberto Devereux (named for a putative lover of Queen Elizabeth I of England). The leading female characters of these three operas are often referred to as "the Three Donizetti Queens." Anna Bolena premiered in 1830 in Milan, to overwhelming success so much so that from then on, Donizetti's teacher addressed his former pupil as Maestro. The opera got a new impetus later at La Scala in 1957, thanks to a spectacular performance by 1 Maria Callas in the title role. Since then, it has been heard frequently, attracting such superstar sopranos as Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Montserrat Caballe. Anna Bolena is based on the historical episode of the fall from favor and death of England’s Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII. -

Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn's Femininity Brought Her Power and Death

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2018 Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ries-Roncalli, Rebecca, "Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death" (2018). Senior Honors Projects. 111. https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/111 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli Senior Honors Project May 2, 2018 Ries-Roncalli 1 I. Adding Dimension to an Elusive Character The figure of Anne Boleyn is one that looms large in history, controversial in her time and today. The second wife of King Henry VIII, she is most well-known for precipitating his break with the Catholic Church in order to marry her. Despite the tremendous efforts King Henry went to in order to marry Anne, a mere three years into their marriage, he sentenced her to death and immediately married another woman. Popular representations of her continue to exist, though most Anne Boleyns in modern depictions are figments of a cultural imagination.1 What is most telling about the way Anne is seen is not that there are so many opinions, but that throughout over 400 years of study, she remains an elusive character to pin down. -

The English Concert – Biography

The English Concert – Biography The English Concert is one of Europe’s leading chamber orchestras specialising in historically informed performance. Created by Trevor Pinnock in 1973, the orchestra appointed Harry Bicket as its Artistic Director in 2007. Bicket is renowned for his work with singers and vocal collaborators, including in recent seasons Lucy Crowe, Elizabeth Watts, Sarah Connolly, Joyce DiDonato, Alice Coote and Iestyn Davies. The English Concert has a wide touring brief and the 2014-15 season will see them appear both across the UK and abroad. Recent highlights include European and US tours with Alice Coote, Joyce DiDonato, David Daniels and Andreas Scholl as well as the orchestra’s first tour to mainland China. Harry Bicket directed The English Concert and Choir in Bach’s Mass in B Minor at the 2012 Leipzig Bachfest and later that year at the BBC proms, a performance that was televised for BBC4. Following the success of Handel’s Radamisto in New York 2013, Carnegie Hall has commissioned one Handel opera each season from The English Concert. Theodora followed in early 2014, which toured West Coast of the USA as well as the Théâtre des Champs Elysées Paris and the Barbican London followed by a critically acclaimed tour of Alcina in October 2014. Future seasons will see performances of Handel’s Hercules and Orlando. The English Concert’s discography includes more than 100 recordings with Trevor Pinnock for Deutsche Grammophon Archiv, and a series of critically acclaimed CDs for Harmonia Mundi with violinist Andrew Manze. Recordings with Harry Bicket have been widely praised, including Lucy Crowe’s debut solo recital, Il caro Sassone. -

Penelope Cave Jane Clark Raymond Head Helena Brown Professor Barry Ife Dr. Micaela Schmitz Paul Y. Irvin Michael Ackerman

Issue No. 3 Published by The British Harpsichord Society NOVEMBER 2010 Guest Editor- PENELOPE CAVE, A prize-winning harpsichordist and well known as a teacher of the instrument, is currently working towards a PhD on ‘Music Lessons in the English Country House’ at the University of Southampton. CONTENTS Editorial and Introductions to the individual articles Penelope Cave Reading between the Lines – Couperin’s instructions for playing the Eight Preludes from L’Art de toucher le clavecin. Penelope Cave ‘Whence comes this strange language?’ Jane Clark Writing Harpsichord Music Today. Raymond Head We live in such fortunate times… Helena Brown The Gift of Music. Professor Barry Ife A Joint Outing with the British Clavichord Society. A visit to Christopher Hogwood’s collection Dr. Micaela Schmitz Historical Keyboard Instruments- the Vocal Ideal, and other Historical Questions. Paul Y. Irvin An Organ for the Sultan. Michael Ackerman and finally.. Your Queries and Questions…..hopefully answered. Please keep sending your contributions to [email protected] . Please note that opinions voiced here are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the BHS. All material remains the copyright of the individual authors and may not be reproduced without their express permission. EDITORIAL The editorship of Sounding Board has fallen to me this Autumn, and I have the challenging but interesting task of accepting the baton, knowing it is, literally, for a season only as I shall pass it on to the next editor as soon as I have completed this issue. In addition to a passion for playing the harpsichord, we all have our specialities and as Pamela Nash was able to give a focus on contemporary matters and William Mitchell concentrated on the instrument and its makers, I wanted to present some articles concerning learning the harpsichord, with which intention I submit something on the Couperin Preludes. -

Purcell Celebration

Performers Ellen McAteer, soprano* Bronwyn Thies-Thompson, soprano* Janelle Lucyk, soprano* Tilford Bach Festival Daniel Taylor, countertenor* (CIO) Robin Blaze, countertenor Ryan McDonald, countertenor* Welcome to all the Pleasures Charles Daniels, tenor Ben Smith, tenor Celebrating William Purcell Alex Dobson, bass* Joel Allison, bass* London Handel Orchestra Adrian Butterfield, violin/director Oliver Webber, violin Darren Moore, trumpet 1 Rachel Byrt, viola Stephen Keavy, trumpet 2 Katherine Sharman, bass violin Sarah Humphreys, oboe 1/recorder 2 Dai Miller, theorbo Catherine Latham, oboe 2/recorder 1 Silas Wollston, organ Theatre of Early Music The singers marked with a * are from the Theatre of Early Music Founded by Artistic Director and Conductor Daniel Taylor, the Theatre of Early Music (TEM) are sought-after interpreters of magnificent yet neglected choral repertoire from four centuries. The core of the TEM consists of an ensemble based in Canada that is primarily made up of young musicians. Their appearances include stunning a cappella programs, with practices and aesthetics of former ages informing thought- provoking, passionate and committed reconstructions of music for historical events and major works from the oratorio tradition. Through their concert performances and recordings, the 10 - 18 solo singers offer a purity and clarity in their sound which has resulted in invitations from an ever-widening circle of the world’s leading stages. Directed by Adrian Butterfield The Theatre of Early Music (TEM) records exclusively for Sony Classical Masterworks London Handel Players and they have been working on new recordings during this visit to England. 17 June 2017 www.tilbach.org.uk Henry Purcell Programme Henry Purcell was one of the greatest English composers, flourishing in the period that followed the Restoration of the monarchy after the Puritan Commonwealth period.