By Katie Hornstein a Dissertation Submit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delaroche's Napoleon in His Study

Politics, Prints, and a Posthumous Portrait: Delaroche’s Napoleon in his Study Alissa R. Adams For fifteen years after he was banished to St. Helena, Na- By the time Delaroche was commissioned to paint Na- poleon Bonaparte's image was suppressed and censored by poleon in his Study he had become known for his uncanny the Bourbon Restoration government of France.1 In 1830, attention to detail and his gift for recreating historical visual however, the July Monarchy under King Louis-Philippe culture with scholarly devotion. Throughout the early phase lifted the censorship of Napoleonic imagery in the inter- of his career he achieved fame for his carefully rendered est of appealing to the wide swath of French citizens who genre historique paintings.2 These paintings carefully repli- still revered the late Emperor—and who might constitute cated historical details and, because of this, gave Delaroche a threat if they were displeased with the government. The a reputation for creating meticulous depictions of historical result was an outpouring of Napoleonic imagery including figures and events.3 This reputation seems to have informed paintings, prints, and statues that celebrated the Emperor the reception of his entire oeuvre. Indeed, upon viewing an and his deeds. The prints, especially, hailed Napoleon as a oval bust version of the 1845 Napoleon at Fontainebleau hero and transformed him from an autocrat into a Populist the Duc de Coigny, a veteran of Napoleon’s imperial army, hero. In 1838, in the midst of popular discontent with Louis- is said to have exclaimed that he had “never seen such a Philippe's foreign and domestic policies, the Countess of likeness, that is the Emperor himself!”4 Although the Duc Sandwich commissioned Paul Delaroche to paint a portrait de Coigny’s assertion is suspect given the low likelihood of of Napoleon entitled Napoleon in his Study (Figure 1) to Delaroche ever having seen Napoleon’s face, it eloquently commemorate her family’s connection to the Emperor. -

From Toulon to St Helena

From Toulon to St Helena Digital bibliography 100 titles on Gallica Selected and arranged thematically by the Fondation Napoléon Contents : Years : 1793 , 1795 , 1796 , 1797 , 1798 , 1799 , 1800 , 1801 , 1802 , 1803 , 1804 , 1805 , 1806 , 1807 , 1808 , 1809 , 1810 , 1811 , 1812 , 1813 , 1814 , 1815 , 1815 - 1821 2 Georgin (François) (1801 -1863) Napoléon au siège de Toulon : [estampe] - Georgin sc. De la fabrique de Pellerin, imprimeur-libraire, à Epinal (Vosges) [1834] - 1834 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b550020028 18 septembre – 18 décembre 1793 - Siège de Toulon Berthault (Pierre -Gabriel), Girardet (Abraham) Attaque de la Convention nationale : journée mémorable du 13 vendémiaire An 4.eme de la République Française : [estampe] - Girardet inv. & del. ; Berthault Sculp. Dessinateur du modèle - [s.n.] (Paris) http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8412477w 5 octobre 1795 – Attaque de la convention nationale «Mariage to Josephine.» Caricature anglaise : [estampe] - [s.n.] http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6940826z 9 mars 1796 – Mariage de Napoléon à Joséphine Bonaparte : général en chef de l'armée françoise en Italie : [estampe] - [s. n.] (Allemagne ?) - 1796-1799 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6953485n 2 mars 1796 – Bonaparte, nommé général en chef de l’armée d’Italie Bataille de Montenotte le 23 germinal an IV : Bonaparte G énéral en Chef. Déroute complète des ennemis, avec perte de 4000 hommes dont 2500 prisonniers, prise de plusieurs Drapeaux et Canons : [estampe] chez Basset (A Paris) – 1796 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6953502q 12 avril 1796 – Bataille de Montenotte 3 Duplessi -Bertaux, Masquelier (Louis -Joseph), Vernet (Carle) Bataille de Millesimo, le 25 [i.e. 24] Germinal , An 4 : [estampe] / dessiné par Carle Vernet ; gravé à l'eau forte par D. -

Daxer & Marschall 2015 XXII

Daxer & Marschall 2015 & Daxer Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com XXII _Daxer_2015_softcover.indd 1-5 11/02/15 09:08 Paintings and Oil Sketches _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 1 10/02/15 14:04 2 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 2 10/02/15 14:04 Paintings and Oil Sketches, 1600 - 1920 Recent Acquisitions Catalogue XXII, 2015 Barer Strasse 44 I 80799 Munich I Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 I Fax +49 89 28 17 57 I Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] I www.daxermarschall.com _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 3 10/02/15 14:04 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 4 10/02/15 14:04 This catalogue, Paintings and Oil Sketches, Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings and Oil Sketches erreicht Sie appears in good time for TEFAF, ‘The pünktlich zur TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht. TEFAF 12. - 22. März 2015, dem Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres. is the international art-market high point of the year. It runs from 12-22 March 2015. Das diesjährige Angebot ist breit gefächert, mit Werken aus dem 17. bis in das frühe 20. Jahrhundert. Der Katalog führt Ihnen The selection of artworks described in this einen Teil unserer Aktivitäten, quasi in einem repräsentativen catalogue is wide-ranging. It showcases many Querschnitt, vor Augen. Wir freuen uns deshalb auf alle Kunst- different schools and periods, and spans a freunde, die neugierig auf mehr sind, und uns im Internet oder lengthy period from the seventeenth century noch besser in der Galerie besuchen – bequem gelegen zwischen to the early years of the twentieth century. -

A Short History of Egypt – to About 1970

A Short History of Egypt – to about 1970 Foreword................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. Pre-Dynastic Times : Upper and Lower Egypt: The Unification. .. 3 Chapter 2. Chronology of the First Twelve Dynasties. ............................... 5 Chapter 3. The First and Second Dynasties (Archaic Egypt) ....................... 6 Chapter 4. The Third to the Sixth Dynasties (The Old Kingdom): The "Pyramid Age"..................................................................... 8 Chapter 5. The First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties)......10 Chapter 6. The Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties (The Middle Kingdom).......11 Chapter 7. The Second Intermediate Period (about I780-1561 B.C.): The Hyksos. .............................................................................12 Chapter 8. The "New Kingdom" or "Empire" : Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties (c.1567-1085 B.C.)...............................................13 Chapter 9. The Decline of the Empire. ...................................................15 Chapter 10. Persian Rule (525-332 B.C.): Conquest by Alexander the Great. 17 Chapter 11. The Early Ptolemies: Alexandria. ...........................................18 Chapter 12. The Later Ptolemies: The Advent of Rome. .............................20 Chapter 13. Cleopatra...........................................................................21 Chapter 14. Egypt under the Roman, and then Byzantine, Empire: Christianity: The Coptic Church.............................................23 -

Charles-Horace Vernet, Dit Carle (D'après) (Bordeaux, 1758

CHARLES-HORACE VERNET, DIT CARLE (D’APRÈS) de ports de France pour Louis XV, soit la plus Avant de s’éteindre en 1836, une légénde fait prononcer (Bordeaux, 1758 - Paris, 1836) grande commande royale de peintures du règne. ces mots à Carle Vernet : « C’est singulier comme Chasse de Napoléon Ier au bois de Boulogne Joseph init ie très tôt le petit Carle en lui je ressemble au Grand Dauphin : fils de roi, père de Huile sur toile mettant entre les mains des pinceaux et en roi, jamais roi ». La réalité est légèrement différente. 1811-1812 lui faisant rencontrer les plus illustres artistes La famille est si illustre qu’Arthur Conan Doyle fait de Dépôt du musée de la Malmaison, 1952 de son temps : Chardin, Van Loo, Vien et Elisabeth son héros Sherlock Holmes un descendant d’une soeur Vigée-Lebrun. d’un des peintres Vernet, sans préciser lequel. L’ORIGINAL ET LA COPIE Le jeune garçon se révèle être un élève doué. Il remporte le prestigieux Prix de Rome en 1782 pour La parabole de LES CHASSES DU PREMIER EmPIRE Commandée par Napoléon Ier, cette Chasse au bois l’enfant prodigue (non localisée) et, en 1789, il est admis à de Boulogne participe à la propagande autour de l’Académie Royale de peinture comme peintre d’histoire, Napoléon Bonaparte réinstaure une vénerie officielle la vénerie de l’empereur. Fin communiquant, Napoléon statut le plus prestigieux, avec Le Triomphe dès 1802. Cette dernière avait été abolie avec tous les utilise l’art pour donner au monde l’image d’un souverain de Paul-Émile (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). -

Mons Memorial Museum Hosts Its First Temporary Exhibition, One Number, One Destiny

1 Press pack PRESS RELEASE From 13 June to 27 September 2015 , Mons Memorial Museum hosts its first temporary exhibition, One number, one destiny. Serving Napoleon . In a unique visitor experience , the exhibition offers a chance to relive the practice of conscription as used during the period of French rule from the Battle of Jemappes (1792) to the Battle of Waterloo (1815). This first temporary exhibition expresses the desire of the new military history museum of the City of Mons to focus on the visitor experience . The conventional setting of the chronological historical exhibition has been abandoned in favour of a far more personal immersion . The basic idea is to give visitors a sense of the huge impact of conscription on the lives of people at the time. With this in mind, each visitor will draw a number by lot to decide whether or not he or she has been ‘conscripted’, and so determine the route taken through the exhibition – either the section presenting the daily existence of conscripts recruited to serve under the French flag, or that focusing on life for the civilians who stayed at home . Visitors designated as conscripts will find out, through poignant letters, objects and other exhibits, about the lives of the soldiers – many of them ill-fated – as they made their way right across Europe in the fight against France’s enemies. Meanwhile, visitors in the other group will learn how those who stayed behind in Mons saw their daily lives turned upside-down by the numerous reforms introduced under the French, including the adoption of a new calendar, the eradication of references to religion, the acquisition of the right to vote, access to a new economic market and exposure to new cultural influences. -

Legislative Assembly Approve Laws/Declarations of War Must Pay Considerable Taxes to Hold Office

Nat’l Assembly’s early reforms center on the Church (in accordance with Enlightenment philosophy) › Take over Church lands › Church officials & priests now elected & paid as state officials › WHY??? --- proceeds from sale of Church lands help pay off France’s debts This offends many peasants (ie, devout Catholics) 1789 – 1791 › Many nobles feel unsafe & free France › Louis panders his fate as monarch as National Assembly passes reforms…. begins to fear for his life June 1791 – Louis & family try to escape to Austrian Netherlands › They are caught and returned to France National Assembly does it…. after 2 years! Limited Constitutional Monarchy: › King can’t proclaim laws or block laws of Assembly New Constitution establishes a new government › Known as the Legislative Assembly Approve laws/declarations of war must pay considerable taxes to hold office. Must be male tax payer to vote. Problems persist: food, debt, etc. Old problems still exist: food shortages & gov’t debt Legislative Assembly can’t agree how to fix › Radicals (oppose monarchy & want sweeping changes in gov’t) sit on LEFT › Moderates (want limited changes) sit in MIDDLE › Conservatives (uphold limited monarchy & want few gov’t changes) sit on RIGHT Emigres (nobles who fled France) plot to undo the Revolution & restore Old Regime Some Parisian workers & shopkeepers push for GREATER changes. They are called Sans-Culottes – “Without knee britches” due to their wearing of trousers Monarchs & nobles across Europe fear the revolutionary ideas might spread to their countries Austria & Prussia urge France to restore Louis to power So the Legislative Assembly ………. [April 1792] Legislative Assembly declares war against Prussia and Austria › Initiates the French Revolutionary Wars French Revolutionary Wars: series of wars, from 1792-1802. -

Nu 40118 Or Er 0 H0

TH E l LLUSTRlOUil O RDER O F H OEBPI’PA LEM A N D K N I G H T S O F T . O H N O F E R L E M S J J US A . P ET ER G ERA RD T H E F O UND E R , , A N D T H E TH RE E GRE AT G R A N D MASTE RS OF T H E I L L U S N J E T R I U S O R D E R O S T . O O O F J H F R U S A L E M . r a n d In s el ec tin g th e thre e g m asters of th e Hospitalers , who . for their ability to organize and c om m and in battle . to assau lt or defend a fortre ss or city , or rule and govern so mix ed a body of m en of so m any langu ages as c onstit u te d The Illustrious Knights of S t . J ohn , of Palestine , Rhodes , and M alta , from their organi za A 9 A D D . 1 7 8 . tion 1 1 0 0 . to , and p articularly th e thre e to whom in ou r j ud gment the honor belongs for m uc h of the glory whic h a t a t ac hes to th e Order of the Kni ghts of M alt . we c annot be far “ du wrong w hen we nam e Raym ond Puy , Phi lip Villi ers de L Isl e Adam , and John de la Vale tte . -

1 BIBLIOGRAPHIE EXHAUSTIVE ET CHRONOLOGIQUE Stéphane

1 BIBLIOGRAPHIE EXHAUSTIVE ET CHRONOLOGIQUE Stéphane CASTELLUCCIO Chargé de recherche au CNRS, HDR Centre André Chastel UMR 8150 OUVRAGES 1. Le Château de Marly pendant le règne de Louis XVI, Prix Cailleux 1990, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, collection scientifique Notes et documents des musées de France n° 29, 1996, 271 pages. 2. Le Style Louis XIII, Paris, Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 142 pages. 3. Les Collections royales d’objets d’art de François Ier à la Révolution, préface d’Antoine Schnapper, professeur émérite à l’université de Paris IV-La Sorbonne, Paris, Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 271 pages. Ouvrage récompensé par le Grand Prix de l’Académie de Versailles, Société des sciences morales, des lettres et des arts d’Ile de France en octobre 2003. 4. Les Carrousels en France du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, L’Insulaire-Les Editions de l’Amateur, 2002, 172 pages. 5. Le Garde-Meuble de la Couronne et ses intendants, du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 2004, 333 pages. Epuisé. Réédité en 2007. 6. Les Fastes de la Galerie des Glaces. Recueil d’articles du Mercure galant. (1681-1773), présentation et annotations, Paris, Payot & Rivages, 2007. 7. Les Meubles de pierres dures de Louis XIV et l’atelier des Gobelins, Dijon, Editions Faton, 2007, 145 pages. 8. Le Goût pour les porcelaines de Chine et du Japon à Paris aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Saint-Rémy-en- l’Eau, Editions Monelle Hayot, 2013, 224 pages. Publication en anglais en association avec le J. -

Valeurs De La République

Valeurs de la République Arts plastiques Entre magnifier et caricaturer : prendre position « Ce n’est pas précisément de la caricature, c’est de l’histoire, de la triviale et triste réalité ». Charles BAUDELAIRE Inspection d’Académie – Inspection Pédagogique Régionale Etymologie La caricature, du latin caricare, signifie « charger ». Elle confère ainsi à la personne figurée une exagération des défauts et vient grossir les traits à des fins comiques ou satiriques. « Les caricatures développent, en exagérant les fromes, les caractères différents des physionomies, et c’est d’après quelques-unes de ces exagérations que des auteurs ou des artistes, conduits par l’imagination, ont trouvé et fait apercevoir des ressemblances visibles et frappantes entre divers animaux et certaines physionomies. » Dictionnaire des Beaux-Arts. « La caricature est un miroir qui grossit les traits et rend les formes plus sensibles. » Claude-Henri Watelet Pour Baudelaire, la caricature représente la modernité dans l’art. La caricature figure un être « sous un aspect rendu volontairement affreux, difforme, odieux ou ridicule. » Etienne Souriau, Vocabulaire d’Esthétique, 1990. Pour Ernst Gombrich, la caricature suppose de « comprendre la différence entre la ressemblance et l'équivalence ». Les formes artistiques de caricatures : Le dessin de presse Les grotesques Les caricatures picturales Le dessin satirique Les photomontages Les sculptures caricaturales Corpus Les œuvres proposées ne sont pas exhaustives, elles permettent d’aborder la notion de Caricature dans les arts selon des orientations qu’il est judicieux d’interroger dans le cadre d’une pratique plasticienne réfléchie et en lien avec une culture artistique justifiée. - Rufus est (c'est Rufus), atrium, Villa des Mystères de Pompéi, Italie. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

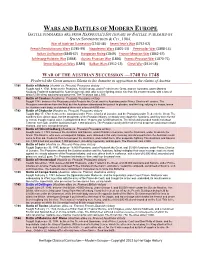

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners.