Copyright by Vladyslav Christian Alexander 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Request for Proposal (Rfp)

DocuSign Envelope ID: 4DABA874-ACB7-46C6-9DC0-5CED7B37BB56 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) DATE: January 28, 2021 All interested REFERENCE: 14-2021-UNDP-UKR-RFP-RPP Dear Sir / Madam: We kindly request you to submit your Proposal for conducting services of “Conducting situation analysis and assessment of needs in hromadas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts”. Please be guided by the form attached hereto as Annex 2, in preparing your Proposal. Proposals may be submitted on or before 23:59 (Kyiv time) Thursday, February 11, 2021 and via email to the address below: United Nations Development Programme [email protected] Procurement Unit Your Proposal must be expressed in the English or Ukrainian or Russian and valid for a minimum period of 90 days. In the course of preparing your Proposal, it shall remain your responsibility to ensure that it reaches the address above on or before the deadline. Proposals that are received by UNDP after the deadline indicated above, for whatever reason, shall not be considered for evaluation. If you are submitting your Proposal by email, kindly ensure that they are signed and in the .pdf format, and free from any virus or corrupted files. NB. The Offeror shall create 2 archive files (*.zip format only!): one should include technical proposal, another one should include financial proposal and be encrypted with password. Both files should be attached to the email letter. During evaluation process only technically compliant companies will be officially asked by UNDP procurement unit via email to provide password to archive with financial proposal. Please do not include the password either to email letter or technical proposal and disclose before official request. -

Огляд Поширення Та Морфометричні Особливості Сліпачка Ellobius Talpinus (Arvicolidae) У Регіоні Нижнього Подніпров’Я (Україна)

Праці Теріологічної Школи. Том 12 (2014): 89–101 Proceedings of the Theriological School. Vol. 12 (2014): 89–101 УДК 599.323.4 (477) ОГЛЯД ПОШИРЕННЯ ТА МОРФОМЕТРИЧНІ ОСОБЛИВОСТІ СЛІПАЧКА ELLOBIUS TALPINUS (ARVICOLIDAE) У РЕГІОНІ НИЖНЬОГО ПОДНІПРОВ’Я (УКРАЇНА) Марина Коробченко, Ігор Загороднюк, Костянтин Редінов Національний науково-природничий музей НАН України Регіональний ландшафтний парк «Кінбурнська коса» E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Review of Distribution and Morphometric Peculiarities of the Mole Vole Ellobius talpinus (Arvicolidae) in the Lower Dnipro River Region (Ukraine). — Korobchenko, M., Zagorodniuk, I., Redinov, K. — The northern mole vole is known in the right-bank Dnipro region from three old (1928–1936) and three modern (1995–2014) locations. Described settlements are confined to steppe communities preserved in branched steppe ravines that run down to the Dnipro River, throughout the area from Berislav city in the Kherson Region to the vicinities of Ordzhonikidze city in the Dnipropetrovsk Region. Recently found locations represent relatively strong and viable populations, which were obviously completely isolated from each other. The strongest popula- tion is in the Virivka and the Mylove groups of settlements (Beryslav District). According to morphometric fea- tures analyzed in the old collection and new samples (n = 13), mole voles from the right bank of Dnipro Region (n = 6) did not significantly differed from ones of Azov populations, except for a slightly larger body length (110 mm against 102 mm). We suggest an existence of a far larger number of existing settlements of this spe- cies in the region because the voles were found in all three checked locations. -

2012, XLVII: 59-66 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca TAXONOMIC IMPLICATIONS of MULT

Contribuţii Botanice – 2012, XLVII: 59-66 Grădina Botanică “Alexandru Borza” Cluj-Napoca TAXONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF MULTIVARIATE MORPHOMETRICS IN SELECTED TAXA OF THE GENUS ASTRAGALUS SECT. DISSITIFLORI (FABACEAE) László BARTHA1, János P. TÓTH2, Attila MOLNÁR V.3, Nicolae DRAGOȘ1,4,5, Gábor SRAMKÓ3,6 1 Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai, Institutul pentru Cercetări Interdisciplinare ȋn Bio-Nano-Ştiinţe, str. A. Treboniu Laurean, nr. 42, RO-400271 Cluj-Napoca, România 2 Department of Evolutionary Zoology and Human Biology, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1, H 4032 Debrecen, Hungary 3 Department of Botany, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1, H-4032 Debrecen, Hungary 4 Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai, Facultatea de Biologie şi Geologie, str. Clinicilor, nr. 5-7, RO-400006 Cluj-Napoca, România 5 Institul de Cercetări Biologice, str. Republicii, nr. 48, RO-400015 Cluj-Napoca, România 6 MTA-ELTE-MTM Ecology Research Group, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/C, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The taxonomy of Astragalus sect. Dissitiflori from Europe is shaped by a controversial nomenclatural history and considerable morphological variation that requires numerical methods to facilitate species delimitation. Besides molecular methods, multivariate analysis of morphological traits has long been recognised to offer important and often complementary evidence in taxonomic research. We applied Multiple Discriminant Analysis based on 14 field-measured morphological characters to test the phenetic distinctiveness of A. pseudoglaucus, A. tarchankuticus, A. vesicarius s.l., A. peterfii and A. pallescens. In addition, we attempted to find the most discriminative morphological traits that separate the taxa investigated. Distinctness of A. tarchankuticus from A. pseudoglaucus and A. vesicarius is clear, whereas the latter two taxa are fairly close to each other. -

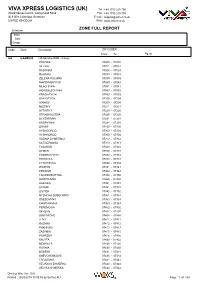

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

VOLCANO a Film by Roman Bondarchuk Ukraine / Germany / Monaco, 2018, 103 Min, Color, Ukrainian / English Language with English Subtitles

VOLCANO a film by Roman Bondarchuk Ukraine / Germany / Monaco, 2018, 103 min, color, Ukrainian / English language with English subtitles Produced by: Olena Yershova (Tato Film) Co-produced by: Tanja Georgieva (elemag pictures), Michel Merkt (KNM), Dar’ya Averchenko (South) With financial support from: Ukrainian State Film Agency and MDM Fund (Germany) Credits: Vadym Ilkov WORLD PREMIERE Karlovy Vary International Film Festival 2018 (East of the West Competition) WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS Pluto Film Distribution Network GmbH NOISE Film PR Phone: +49 (0) 30 21 91 82 20 Mirjam Wiekenkamp E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +49 (0)176 28771839 E-mail: [email protected] Film stills can be downloaded here (credits: Vadym Ilkov): https://bit.ly/2kA6hTV CONTENTS Logline Synopsis About the director Director’s statement Cast About the region Interview with Roman Bondarchuk & Dar’ya Averchenko About the producers Specs & Credits Credits: Vadym Ilkov Credits: Vadym Ilkov LOGLINE Lukas, an interpreter for a military mission, gets lost near a remote Ukrainian village and stumbles from simple misadventure into the weirdest road trip of his life. SYNOPSIS A series of odd coincidences has left Lukas, an interpreter for a military checkpoint inspection tour, stranded near a remote town in the south Ukrainian steppe. With nowhere to turn, this city boy finds shelter at the home of a colorful local named Vova. With Vova as his guide, Lukas is confronted by an anarchist universe beyond his imagination, a world in which life seems utterly detached from any identifiable structure. Fascinated by his host and his host's daughter Marushka, Lukas’s contempt for provincial life slowly melts away and sets him on a quest for a happiness he never knew could exist. -

Rodentia, Cricetidae), at the Western Bank of the Dnipro River, Ukraine

Vestnik zoologii, 49(3): 261–266, 2015 Ecology DOI 10.1515/vzoo-2015-0027 UDC 599.323.42 (477.4) REDISCOVERY OF THE NORTHERN MOLE VOLE, ELLOBIUS TALPINUS (RODENTIA, CRICETIDAE), AT THE WESTERN BANK OF THE DNIPRO RIVER, UKRAINE M. Rusin1*, H. Rashevska1, Y. Mylobog2, V. Stryhunov2 1Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, NAS of Ukraine, vul. B. Khmelnitskogo, 15, Kiev, 01030 Ukraine 2Kryvyi Rih National University, ХХІІ Partz’izdu 11, str., Kryvyi Rih, 50027 Ukraine *corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Rediscovery of the Northern Mole Vole, Ellobius talpinus (Rodentia, Cricetidae), at the Western Bank of the Dnipro River, Ukraine. Rusin, M., Rashevska, H., Milobog, Y., Strigunov, V. — Ellobius talpinus was supposed to become extinct from the westernbank of the river Dnipro. Aft er 50 years the species was found again in Dnipropetrovsk and Kherson Region. Th e brief description of the current distribution of the northern mole vole to the west of the Dnipro is given. Altogether 11 localities were found. Th e rediscovered populations may be treated as endangered in the region. Key words : Ellobius talpinus, distribution, Eastern Europe. Переоткрытие обыкновенной слепушонки, Ellobius talpinus (Rodentia, Cricetidae), на западном берегу Днепра,Украина. Русин М., Рашевская А., Милобог Ю., Стригунов В. —Ellobius talpinus длительное время считалась вымершим видом к западу от Днепра. После 50 лет вид был повторно найден в Днепропетровской и Херсонской областях. Приводится краткое описание современного распространения обыкновенной слепушонки к западу от Днепра. Всего было обнаружено 11 локалитетов. Обнаруженные популяции находятся под угрозой исчезновения в регионе. Ключевые слова: Ellobius talpinus, распространение, Украина. Introduction Th e northern mole vole, Ellobius talpinus (Pallas, 1773), is a widespread species of the genus Ellobius, a group of subterranean rodents of the family Cricetidae. -

A Survey of the Weevils of Ukraine. Bark and Ambrosia Beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae and Scolytinae)

Zootaxa 3912 (1): 001–061 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3912.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2FB36894-6601-4665-A2B4-550149B5F7E9 ZOOTAXA 3912 A survey of the weevils of Ukraine. Bark and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae and Scolytinae) TATYANA NIKULINA1,*, MIKHAIL MANDELSHTAM2, 3, ALEXANDER PETROV4, VITALIJ NAZARENKO5 & NIKOLAI YUNAKOV6 1Donetsk National University, Biological Faculty, Department of Zoology and Ecology, Shchorsa, 46, Donetsk, 83050, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 2Saint-Petersburg State Forest Technical University, Centre for Bioinformatics and Genome Research, Institutsky per., 5, St.Peters- burg, 194021, Russia 3Saint-Petersburg State University, Universitetskaya nab., 7/9, St.Petersburg, 199034, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 4Institute of Forest Science RAS, Sovetskaya st., 21, Uspenskoe, Moscow Region, 143030, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 5Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Bohdan Khmel’nitskiy, 15, 01601, Kyiv, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 6University of Oslo, Natural History Museum, Department of Zoology, P.O. Box 1172 Blindern, NO-0318 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by L. Kirkendall: 14 Oct. 2014; published: 22 Jan. 2015 TATYANA NIKULINA, MIKHAIL MANDELSHTAM, ALEXANDER PETROV, VITALIJ NAZARENKO & NIKOLAI YUNAKOV A survey of the weevils of Ukraine. Bark and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae and Scolytinae) (Zootaxa 3912) 61 pp.; 30 cm. 22 Jan. 2015 ISBN 978-1-77557-625-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-626-6 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2015 BY Magnolia Press P.O.