Common Clarinet Misconceptions Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Jodyjazz Super Jet Tenor Sax Mouthpiece

Toolshed Sax Dakota SDT-XR 52 Tenor Saxophone Highly Responsive, Aesthetically Detailed he SDT-XR 52 Tenor Saxophone from Sax Dakota is an ergo- King Zephyr saxophone models), and I was pleased to nomically deigned, aesthetically detailed and highly respon- find that choosing one over another really did make a Tsive instrument. It’s the company’s top-line tenor, made of difference in airstream control and physical comfort. raw bronze with a semi-matte Black Onyx finish on the body, bow Additional professional touches include a con- and bell, and a bright Black Onyx finish on the inside of the bell. veniently located front high-F lever, an adjust- The SDT-XR 52’s neck is silver-plated, and the keywork, trim and able right-hand thumb rest and a high F# key. grille-style keyguards are unfinished, sporting a distinct art deco-like Stainless steel key rods help enhance the action. design. The neck and bell are decorated with attractive hand-engrav- Black oxide steel springs and pivot screws ing. The raw bronze body of the SDT-XR 52 is essentially a brass alloy team with custom Italian pads and tone with increased copper content (77 percent), resulting in a smooth and boosters. The reinforced double arms on the highly resonant sound that’s reminiscent of certain post-World War low C/B/B-flat keys, along with Pisoni Pro II vintage horns. Playing it, I experienced a pleasing feeling of vibra- key pads, are designed to aid response and tion in the instrument’s body, even on upper-stack fingerings. -

Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur Gmbh the World's Oldest Accordion

MADE IN GERMANY Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH The world’s oldest accordion manufacturer | Since 1852 Our “Weltmeister” brand is famous among accordion enthusiasts the world over. At Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH, we supply the music world with Weltmeister solo, button, piano and folklore accordions, as well as diatonic button accordions. Every day, our expert craftsmen and accordion makers create accordions designed to meet musicians’ needs. And the benchmark in all areas of our shop is, of course, quality. 160 years of instrument making at Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH in Klingenthal, Germany, are rooted in sound craftsmanship, experience and knowledge, passed down carefully from master to apprentice. Each new generation that learns the trade of accordion making at Weltmeister helps ensure the longevity of the company’s incomparable expertise. History Klingenthal, a centre of music, is a small town in the Saxon Vogtland region, directly bordering on Bohemia. As early as the middle of the 17th century, instrument makers settled down here, starting with violin makers from Bohemia. Later, woodwinds and brasswinds were also made here. In the 19th century, mouth organ ma- king came to town and soon dominated the townscape with a multitude of workshops. By the year 1840 or thereabouts, this boom had turned Klingenthal into Germany’s largest centre for the manufacture of mouth organs. Production consolidation also had its benefits. More than 30 engineers and technicians worked to stre- Accordion production started in 1852, when Adolph amline the instrument making process and improve Herold brought the accordion along from Magdeburg. quality and customer service. A number of inventions At that time the accordion was a much simpler instru- also came about at that time, including the plastic key- ment, very similar to the mouth organ, and so it was board supported on two axes and the plastic and metal easily reproduced. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Instruments of the Orchestra

INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA String Family WHAT: Wooden, hollow-bodied instruments strung with metal strings across a bridge. WHERE: Find this family in the front of the orchestra and along the right side. HOW: Sound is produced by a vibrating string that is bowed with a bow made of horse tail hair. The air then resonates in the hollow body. Other playing techniques include pizzicato (plucking the strings), col legno (playing with the wooden part of the bow), and double-stopping (bowing two strings at once). WHY: Composers use these instruments for their singing quality and depth of sound. HOW MANY: There are four sizes of stringed instruments: violin, viola, cello and bass. A total of forty-four are used in full orchestras. The string family is the largest family in the orchestra, accounting for over half of the total number of musicians on stage. The string instruments all have carved, hollow, wooden bodies with four strings running from top to bottom. The instruments have basically the same shape but vary in size, from the smaller VIOLINS and VIOLAS, which are played by being held firmly under the chin and either bowed or plucked, to the larger CELLOS and BASSES, which stand on the floor, supported by a long rod called an end pin. The cello is always played in a seated position, while the bass is so large that a musician must stand or sit on a very high stool in order to play it. These stringed instruments developed from an older instrument called the viol, which had six strings. -

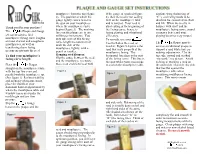

Thank You for Your Purchase! the ® Plaque and Gauge Set Can Be Used to Find Mouthpiece Facing Curve Lengths on Most Clarinet A

mouthpiece from the top (figure If the gauge is crooked (figure airplane wing (balancing of 2). The position at which the 4), then the reed is not sealing “C”), each wing needs to be ® gauge lightly comes to rest is well on the mouthpiece table identical for consistent air-flow MADE IN USA the spot on your mouthpiece and is warped. Your reed is and lift. When the reed is in Thank you for your purchase! where the mouthpiece curve also leaking at the beginning of balance with itself and the begins (figure 3). The marking the facing curve, hence, is mouthpiece facing curve, sound The ® Plaque and Gauge lines on the plaque are in one losing playing and vibrational resonates better and your set can be used to find millimeter increments. You efficiency. playing becomes very natural. mouthpiece facing curve lengths may take note of this facing To remedy, use your ® on most clarinet and saxophone curve length measurement or Tool to flatten the reed, as The ® Plaque may be mouthpieces, as well as mark the side of the transferring those facing needed. Figure 5 depicts a flat used as a traditional plaque to mouthpiece, lightly, with a reed that seals properly at the support a reed while you are measurements onto the reed. pencil or marker. mouthpiece facing. The making adjustments. Use the To find your mouthpiece’s Gauging reed flatness: horizontal line depicts the start top side, curved end marked facing curve length: Slip the gauge between the reed of the facing curve. This line is “tip work,” see picture. -

Clarinet Quarter-Tone Fingering Chart

Clarinet Quarter-Tone Fingering Chart 1st Edition rev.1 2017 Jason Alder www.jasonalder.com ii Author’s Note This clarinet quarter-tone fingering chart developed as a continuation of my initial work of one for bass clarinet, which grew from my extensive playing of contemporary music and study of South-Indian Karnatic music. My focus had been primarily on bass clarinet, so the development of this chart for soprano clarinet didn’t come to realization until some years later as my own need for it arose, occurring simultaneously with a decision to rework the initial bass clarinet chart into a second edition. The first edition for clarinet therefore follows the same conventions as the second edition bass clarinet fingering chart. This first revision revisits a few quarter-tone fingerings around the “break” after I discovered some better ones to use. Jason Alder London, 2017 iii Guide to the Fingering Chart This fingering chart was made using a Buffet R13 clarinet, and thus the fingerings notated are based on the Boehm system. Because some differences may exist between different manufacturers, it is important to note how this system correlates to your own instrument. In some fingerings I have used the Left Hand Ab//Eb key, which not all instruments have. I’ve included this only when its use is an option, but have omitted the outline when it’s not. Many notes, particularly quarter-tones and altissimo notes, can have different fingerings. I have notated what I found to be best in tune for me, with less regard for ease and fluidity of playing. -

Preliminary Results Clarinet, Flute, Horn, Soprano Singer, Trumpet

Performing Arts Aerosol Study Round one preliminary results Clarinet, Flute, Horn, Soprano Singer, Trumpet Study Chairs James Weaver - NFHS Director of Mark Spede – CBDNA President, Performing Arts and Sports Director of Bands, Clemson University Lead Funders Contributing Organizations Supporting Organizations American School Band Directors Association (ASBDA) International Music Council American String Teachers Association (ASTA) International Society for Music Education Arts Education in Maryland Schools (AEMS) League of American Orchestras Association Européenne des Conservatoires/Académies de Louisiana Music Educators Association Musique et Musikhochschulen (AEC) (LMEA) Buffet et Crampon MidWest Clinic Bundesverband der deutschen Minority Band Directors National Association Musikinstrumentenhersteller e.V Music Industries Association Chicago Children's Choir Musical America Worldwide Children's Chorus of Washington National Dance Education Organization Chorus America (NDEO) Confederation of European Music Industries (CAFIM) National Flute Association (NFA) Drum Corps International (DCI) National Guild for Community Arts Education Educational Theatre Association (EdTA) National Music Council of the US European Choral Association - Europa Cantat Percussive Arts Society (PAS) HBCU National Band Directors' Consortium Save the Music Foundation High School Directors National Association (HSBDNA) WGI Sport of the Arts International Conductors Guild Lead Researchers Dr. Shelly Miller Dr. Jelena Srebric University of Colorado Boulder University -

Bishop Scott Boys' School

BISHOP SCOTT BOYS’ SCHOOL (Affiliated to CBSE, New Delhi) Affiliation No.: 330726, School Campus: Chainpur, Jaganpura, By-Pass, Patna 804453. Phone Number: 7061717782, 9798903550. , Web: www.bishopscottboysschool.com Email: [email protected] STUDY COURSE MATERIAL ENGLISH SESSION-2020-21 CLASS- IX Ch 2- The Sound of Music. Part I - (Evelyn Glennie Listens to Sound without Hearing It) By Deborah Cowley Part I. Word meanings. 1. Profoundly deaf: absolutely deaf. 2. specialist: a doctor specializing in a particular part of the body. 3. Deteriorated: worsened, reduces. 4. Urged: requested. 5. coveted: much desired 6. replicating: making a copy of something 7. yearning – longing, having a desire for something 8. devout: believing strongly in a religion and obeying its laws and following its practices Summary. Evelyn Glennie is a multi – percussionist. She has attained mastery over almost a thousand musical instruments despite being hearing – impaired. She learnt to feel music through the body instead of hearing it through the ears. When Evelyn was eleven years old, it was discovered that she had lost her hearing power due to nerve damage. The specialist advised that she wear hearing aids and be sent to a school for the deaf. On the contrary, Evelyn was determined to lead a normal life and follow her interest in music. Although she was discouraged by her teachers, her potential was noticed by master percussionist, Ron Forbes. He guided Evelyn to feel music some other way than to hear it through her ears. This worked well for Evelyn and she realized that she could sense different sounds through different parts of her body. -

Tutti Brassi

Tutti Brassi A brief description of different ways of sounding brass instruments Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2018 The author’s moral rights have been asserted Hataf Segol Publications 2018 Typeset in XƎLATEX by Simon Montagu Why Mouthpieces 1 Cornets and Bugles 16 Long Trumpets 19 Playing the Handhorn in the French Tradition 26 The Mysteries of Fingerhole Horns 29 Horn Chords and Other Tricks 34 Throat or Overtone Singing 38 iii This began as a dinner conversation with Mark Smith of the Ori- ental Institute here, in connexion with the Tutankhamun trum- pets, and progressed from why these did not have mouthpieces to ‘When were mouthpieces introduced?’, to which, on reflection, the only answer seemed to be ‘Often’, for from the Danish lurs onwards, some trumpets or horns had them and some did not, in so many cultures. But indeed, ‘Why mouthpieces?’ There seem to be two main answers: one to enable the lips to access a tube too narrow for the lips to access unaided, and the other depends on what the trumpeter’s expectations are for the instrument to achieve. In our own culture, from the late Renaissance and Early Baroque onwards, trumpeters expected a great deal, as we can see in Bendinelli’s and Fantini’s tutors, both of which are avail- able in facsimile, and in the concert repertoire from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo onwards. As a result, mouthpieces were already large, both wide enough and deep enough to allow the player to bend the 11th and 13th partials and other notes easily. The transition from the base of the cup into the backbore was a sharp edge. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

Clarinet Tips

Teacher’s Guide by the late Nilo HoveyClarinet Nilo W. Hovey The late Nilo W.Hovey was actively engaged in the school band movement since 1925. From 1926 to 1944 he was Director of School Instrumental Music in the Hammond, Indiana, public schools. From 1944 to 1957 he was Chairman of the Music Education Department and Director of the Concert Band at Butler University, Indianapolis, Indiana. During this period he was the recipient of the J.I. Holcomb award for his contribution to the advancement of the University and the Arthur W. Baxter award for superior teaching. Hovey served as lecturer, clinician, adjudicator and guest conductor in all sections of the United States and in Ontario, Canada. In the latter capacity he appeared with the United States Navy Band, the United States Army Band, the Canadian Air Force Band, and many Intercollegiate and All-State High School Bands. Numerous instrumental methods and books of instructional material written or edited by Hovey are widely used in the schools of the United States and Canada. Hovey was an active member of the American Bandmasters Association for over twenty years and served as its President in 1970-71. He was President of the Music Industry Council in 1962-64. He was an honorary member of the Canadian Bandmasters Association, of Kappa Kappa Psi and Phi Beta Mu. Hovey was also a member of Phi Kappa Phi,Honorary scholastic fraternity,Phi Delta Kappa, fraternity of men in education, and Phi Mu Alpha (Sinfonia). Publications The following Clarinet materials have been written or edited by Mr.