1 International Tennis Federation Independent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesis Monográfica

Universidad del Salvador Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación y de la Comunicación Social Ciclo de Licenciatura en Periodismo Tesis monográfica Tratamiento periodístico sobre dopaje y apuestas ilegales en el tenis Análisis del contenido de los diarios Clarín, de la Argentina; El País, de España, y USA Today, de los Estados Unidos sobre los dos problemas más importantes que afronta el tenis en los últimos años. Realizado por: Pablo Demares Directora de la Carrera de Periodismo: Lic. Erica Walter Tutor de la tesis monográfica: Lic. Norberto Beladrich Asesor metodológico: Prof. Leonardo Cozza Asignatura: Tesina Buenos Aires, 26 de mayo de 2010 [email protected] DNI: 31.685.490 15-6226-4051 0 ABSTRACT El doping y las apuestas ilegales en el tenis se han convertido en los aspectos extradeportivos de la competencia profesional con mayor repercusión en los últimos 15 años. En ese contexto, los medios de comunicación se han encargado de incluir en su contenido artículos de diversos estilos con el objetivo de realizar una cobertura periodística acabada e investigaciones profundas. Sobre ellos será aplicado el Análisis Crítico del Discurso (ACD) postulado, entre otros, por el lingüista y profesor de la Universidad Pompeu Fabra, de Barcelona, Teun Van Dijk. El mismo consiste en un enfoque interdisciplinar que permite detectar en los discursos (a fines de este trabajo, textos de diarios) cómo se reproduce la dominación de un grupo sobre otro y la resistencia que interponen los discursos. De manera más particular, el ACD observa las variantes del racismo en las noticias. Así, su teoría fue aplicada para descubrir que, pese a la existencia de términos que transmitan vetas discriminatorias, los artículos no afectan la interpretación de la información ni influyen en las opiniones u acciones de los lectores. -

Doping in Tennis, Where We Are and Where We Should Be Going?

Performance Enhancement & Health 7 (2020) 100157 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Performance Enhancement & Health journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/peh Doping in tennis, where we are and where we should be going? a,b,∗ a Thomas Zandonai , Darias Holgado a Mind, Brain and Behaviour Research Centre, Department of Experimental Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Granada, Campus De Cartuja s/n, 18071, Granada, Spain b Alicante Institute for Health and Biomedical Research, ISABIAL-FISABIO Foundation, Neuropharmacology on Pain, Miguel Hernández University, Elche, Avda. Pintor Baeza, 12, 03010, Alicante, Spain a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 14 November 2019 Received in revised form 19 December 2019 Accepted 23 January 2020 Available online 31 January 2020 Keywords: Drugs Exercise performance Athletes Health Sports 1. Tennis and anti-doping health and rights of tennis players participating in various compe- titions. The latest WADA report states that 322,050 doping controls Tennis, an ancient royal sport, has seen well-known athletes were performed in all sports in 2017, and that only 1.48 % of tests succumb to doping temptations, committing offences that that can were positive (WADA. World Anti-Doping Agency, 2017). This low potentially jeopardize their entire careers (Maquirriain & Baglione, percentage seems to suggest that doping in sport might not be as big 2016). Doping has now even reached the younger categories of the an issue as people tend to think. However, negative doping tests are sport, with a teenage tennis player recently testing positive for an not necessarily a demonstration that athletes are “clean” we may anabolic-androgenic steroid (TADP. -

Arbitral Award

CAS 2006/A/1025 Mariano Puerta v/ International Tennis Federation (ITF) ARBITRAL AWARD Pronounced by the COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT sitting in the following composition: President : Mr John A. Faylor, Attorney-at-law, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Arbitrators : Mr Denis Oswald, Attorney-at-law, Neuchâtel, Switzerland Mr Peter Leaver QC, Barrister-at-Law, London, England Clerk of the Court : Mr Adrian Holloway, Attorney-at-law, Geneva, Switzerland in the arbitration between Mr Mariano Puerta, Buenos-Aires, Argentina Represented by Mr Eduardo Moliné O’Connor, Mr Santiago Moliné O’Connor, Attorneys- at-law, Buenos Aires, Argentina and Mr Robert Fox, Attorney-at-law, Lausanne, Switzerland as Appellant and International Tennis Federation (ITF), London, England Represented by Mr Jonathan Taylor and Mr Iain Higgins, Solicitors, London, England, as Respondent CAS 2006/A/1025 M. Puerta v/ITF; Page 2 I. FACTS 1. Parties 1.1. The Appellant, Mr Mariano Puerta (“Mr Puerta”), an Argentinian citizen, was born on 19 September 1978. He has been a professional tennis player since about 1995 and a member of the ATP Tour since June 1997. In May 2005, Mr Puerta was ranked as tenth in the ATP world rankings. 1.2. The Respondent, the International Tennis Federation (“the ITF”), is the international federation governing sports related to tennis world wide. The ITF maintains its seat in London, England. Its purpose is, inter alia, “to foster the growth and development of the sport of tennis on a worldwide basis” (see ITF’s Constitution Article IV (a).) 2. Subject Matter of this Appeal; the Doping Offence committed at the French Open on 5 June 2005 and its Sanction as a Second Offence 2.1. -

Edmund Goes for First Career Title Against 2-Time Champ Andujar

GRAND PRIX HASSAN II: DAY 7 MEDIA NOTES Sunday, 15 April 2018 Royal Tennis Club de Marrakech | Marrakech, Morocco | 9-15 April 2018 Draw: S-32, D-16 | Prize Money: €501,345 | Surface: Clay ATP World Tour Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing ATPWorldTour.com FRMT.ma Fabienne Benoit: [email protected] Twitter: @ATPWorldTour @FRMT_maroc Press Room: [email protected] Facebook: @ATPWorldTour FRMT TV & Radio: TennisTV.com EDMUND GOES FOR FIRST CAREER TITLE AGAINST 2-TIME CHAMP ANDUJAR • An experienced champion and a debutante will battle for the Grand Prix Hassan II championship on Sunday, as Pablo Andujar of Spain, the 2011 and 2012 titlist, will take on No.2 seed and first-time participant Kyle Edmund of Great Britain, who has reached the first ATP World Tour final of his career. This is their first Tour-level meeting, although Edmund defeated Andujar in the qualifying rounds at Beijing in 2016. • Andujar, who is ranked No. 355 and playing with a protected ranking of No. 105, has improved his stellar tournament record to 14-2 after winning his quarter-final and semi-final matches on Saturday. The two-time champion is bidding to win ATP Challenger Tour and ATP World Tour titles in consecutive weeks after claiming the Challenger crown in Alicante, Spain. The last player to do that was Ryan Harrison in 2017, going back-to-back in Dallas and Memphis. A victory would also make 32-year-old Andujar the lowest-ranked ATP World Tour singles champion since then-16-year-old Lleyton Hewitt triumphed at Adelaide in 1998, when the Australian was ranked No. -

Evaluating Professional Tennis Players’ Career Performance: a Data Envelopment Analysis Approach

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Evaluating professional tennis players’ career performance: A Data Envelopment Analysis approach Halkos, George and Tzeremes, Nickolaos University of Thessaly, Department of Economics September 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/41516/ MPRA Paper No. 41516, posted 24 Sep 2012 20:02 UTC Evaluating professional tennis players‘ career performance: A Data Envelopment Analysis approach By George E. Halkos and Nickolaos G. zeremes University of Thessaly, Department of Economics, Korai 43, 38333, Volos, Greece Abstract This paper by applying a sporting pro uction function evaluates 229 professional tennis players$ career performance. By applying Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) the paper pro uces a unifie measure of nine performance in icators into a single career performance in ex. In a ition bootstrap techni,ues have been applie for bias correction an the construction of confi ence intervals of the efficiency estimates. The results reveal a highly competitive environment among the tennis players with thirty nine tennis players appearing to be efficient. Keywords: .rofessional tennis players/ Data Envelopment Analysis/ 0port pro uction function/ Bootstrapping. %EL classification: 114' 129' 383. 1 1. Introduction The economic theory behin sporting activity is base on the wor4 of Rottenberg (1952). 7owever, 0cully (1984) was the first to apply a pro uction function in or er to provi e empirical evi ence for the performance of baseball players. 0ince then several scholars have use frontier pro uction function in or er to measure teams$ performance an which has been escribe on the wor4s of 9a4, 7uang an 0iegfrie (1989), .orter an 0cully (1982) an :izel an D$Itri (1992, 1998). -

How Adr Might Save Men's Professional Tennis

ACCEPTING A DOUBLE-FAULT: HOW ADR MIGHT SAVE MEN’S PROFESSIONAL TENNIS Bradley Raboin* Introduction..................................................................... 212 I. History and Structure of Men’s Professional Tennis Today................................................................................ 214 A. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP)..... 214 B. International Tennis Federation (ITF).................. 218 II. Present Governance Structure .................................. 220 III. Modern Difficulties & Issues in Men’s Professional Tennis .............................................................................. 224 A. Player Dissatisfaction............................................. 224 1. Prize Money.......................................................... 224 2. Scheduling ............................................................ 230 B. Match-Fixing ........................................................... 233 C. Doping...................................................................... 235 IV. Present Solutions ...................................................... 237 A. ATP Players’ Council .............................................. 237 B. Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) ..................... 238 C. ATP & ITF Anti-Doping Program.......................... 242 V. Why Med-Arb ADR Is the Solution ........................... 245 A. “Med-Arb” ................................................................ 245 B. Advantages of Med-Arb .......................................... 246 * Bradley -

1882: En La Ciudad De Valparaíso Específicamente En El Cerro De Las Zorras, Es Creada La Primera Cancha De Tenis En Chile, Por Una Iniciativa Del Ciudadano Inglés MR

A continuación detallaremos algunos de los principales hitos del tenis nacional: 1882: En la ciudad de Valparaíso específicamente en el cerro de las Zorras, es creada la primera cancha de tenis en Chile, por una iniciativa del ciudadano inglés MR. Cox. Así como la creación de la primera cancha, después aparecieron la de mister James, en Las Salinas, de mister Hardy, en el camino Cintura, y de mister Shuterland, en la calle del Hospital Inglés. Evidentemente, no se trataba de canchas comparables con las de hoy, sino de ripio, con improvisadas líneas de tablas, o de zunchos clavados con grapas. 1898: El primer vestigio de organización se encuentra en Valparaíso, con la fundación de los clubes International Club y Viña del Mar Lawn Tenis Club. Los datos del desplazamiento del tenis hacia Santiago también son imprecisos, aunque Carlos Ossandon postula que la primera cancha de la capital la instaló un extranjero de apellido Denier, en Avenida Independencia. 1904: En la ciudad de Santiago se crea el primer club del que se tiene registro "Royal Lawn Tennis Club", que funciona hasta hoy con el nombre de "Santiago Lawn Tennis Club", se encuentra ubicado al interior del Parque O'Higgins. Allí creció el talento y la fama de Aurelio Lizana Vera, tío de Anita Lizana, quien fuera cuidador, pasapelotas y cantinero, y llegó a ser uno de los mejores tenistas del país. En esos años también nacieron el Prince of Wales Country Club y el Stade Français, este último de la fusión entre la Societé Française de Lawn Tennis, fundada en 1905, y el Sport Français, de 1924. -

Super Spaniardls Feat of Clay

Ton-up Shikhar Dhawan stars in India’s win over Australia PAGE 15 MONDAY, JUNE 10, 2019 England beat Switzerland on penalties CRICKET WORLD CUP to finish 3rd in Nations League PAGE 14 SOUTH AFRICA VS WI NO STOPPING HISTORY MAN NADAL THIEM NADAL 7 ACES 3 FINAL 1 DOUBLE FAULTS 0 70% FIRST SERVE % 74% 58% WIN % ON 1ST SERVE 73% D. THIEM 3 7 1 1 52% WIN % ON 2ND SERVE 64% 2 BREAK POINTS WON 7 0 TIEBREAKS WON 0 R. NADAL 6 5 6 6 31 RECEIVING POINTS WON 41 82 POINTS WON 116 12 GAMES WON 23 2 MaX GAMES WON IN A ROW 5 Spain’s Rafael Nadal celebrates after the French Open. (AFP) 6 MaX POINTS WON IN A ROW 11 51 SERVICE POINTS WON 75 10 SERVICE GAMES WON 16 Spaniard sweeps to 12th French Rafa Factfile Open and 18th Grand Slam title ● Rafael Nadal Parera ● AFP Nationality: Spanish PARIS ● Born: June 3, 1986 (33) RAFAEL Nadal swept to an ● Height: 6ft 1in (1.86m) historic 12th Roland Garros All time Grand title and 18th Grand Slam ● Plays: Left-handed crown on Sunday with a 6-3, Slam title winners ● Turned pro: 2001 5-7, 6-1, 6-1 victory over Aus- 20: Roger Federer (SUI) tria’s Dominic Thiem. ● 18: Rafael Nadal (ESP) Career prize money: The 33-year-old Spaniard $109,577,186 becomes the first player, man 15: Novak Djokovic (SRB) or woman, to win the same ● Grand Slam titles: 18 Slam 12 times after seeing 14: Pete Sampras (USA) off a brave challenge from a 12: Roy Emerson (AUS) Australian Open (2009), weary Thiem in a repeat of French Open (2005, 2006, the 2018 final. -

EMIRATES ATP RANKINGS FACTS and FIGURES Atpworldtour.Com 2015 Year-End Emirates Atp Rankings

EMIRATES ATP RANKINGS FACTS AND FIGURES ATPWorldTour.com 2015 year-end emirates atp rankings As of November 30, 2015 1 Djokovic,Novak/SRB 64 Andujar,Pablo/ESP 127 Youzhny,Mikhail/RUS 190 Lapentti,Giovanni/ECU 2 Murray,Andy/GBR 65 Kukushkin,Mikhail/KAZ 128 Fratangelo,Bjorn/USA 191 Samper-Montana,Jordi/ESP 3 Federer,Roger/SUI 66 Haase,Robin/NED 129 Smith,John-Patrick/AUS 192 Volandri,Filippo/ITA 4 Wawrinka,Stan/SUI 67 Carreño Busta,Pablo/ESP 130 Coppejans,Kimmer/BEL 193 Przysiezny,Michal/POL 5 Nadal,Rafael/ESP 68 Lorenzi,Paolo/ITA 131 Carballes Baena,Roberto/ESP 194 Gojowczyk,Peter/GER 6 Berdych,Tomas/CZE 69 Kudla,Denis/USA 132 Soeda,Go/JPN 195 Karatsev,Aslan/RUS 7 Ferrer,David/ESP 70 Giraldo,Santiago/COL 133 Elias,Gastao/POR 196 Lamasine,Tristan/FRA 8 Nishikori,Kei/JPN 71 Mahut,Nicolas/FRA 134 Novikov,Dennis/USA 197 Stepanek,Radek/CZE 9 Gasquet,Richard/FRA 72 Cervantes,Iñigo/ESP 135 Donaldson,Jared/USA 198 Sarkissian,Alexander/USA 10 Tsonga,Jo-Wilfried/FRA 73 Almagro,Nicolas/ESP 136 Basic,Mirza/BIH 199 Moriya,Hiroki/JPN 11 Isner,John/USA 74 Pella,Guido/ARG 137 Ymer,Elias/SWE 200 Laaksonen,Henri/SUI 12 Anderson,Kevin/RSA 75 Muñoz-De La Nava,Daniel/ESP 138 Arguello,Facundo/ARG 201 Mertens,Yannick/BEL 13 Cilic,Marin/CRO 76 Lajovic,Dusan/SRB 139 Gombos,Norbert/SVK 202 McGee,James/IRL 14 Raonic,Milos/CAN 77 Lu,Yen-Hsun/TPE 140 Kravchuk,Konstantin/RUS 203 Yang,Tsung-Hua/TPE 15 Simon,Gilles/FRA 78 Pouille,Lucas/FRA 141 Bagnis,Facundo/ARG 204 Halys,Quentin/FRA 16 Goffin,David/BEL 79 Kuznetsov,Andrey/RUS 142 Gonzalez,Alejandro/COL 205 Bourgue,Mathias/FRA -

ATPUMAG #30ATPUMAG OFFICIAL JOURNAL of the ATP TOURNAMENT • No 9 • 22

#ATPUMAG #30ATPUMAG OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE ATP TOURNAMENT • No 9 • 22. 07. 2019. The organizer reserves the right to change the program and timetable. All news in the program can be followed using the official website of the tournament www.croatiaopen.hr. 1 1. FOGNINI, FABIO ITA SINGLES 2. BYE F. FOGNINI [1] S. TRAVAGLIA 3. TRAVAGLIA, STEFANO ITA 6:1, 2:1, retired S. TRAVAGLIA 4. FABBIANO, THOMAS ITA 6:3, 6:2 A. BALAZS Q 5. BALAZS, ATTILA BRA A. BALAZS 3:6, 7:6(2), 6:3 WC 6. GALOVIĆ, VIKTOR CRO 6:0, 6:7(5), 7:6(4) A. BALAZS JPN 7. DANIEL, TARO F. KRAJINOVIĆ 6:3, 6:7(1), 7:6(5) 6 8. KRAJINOVIĆ, FILIP SRB 7:5, 7:6(4) A. BALAZS 3 9. ĐERE, LASLO SRB 6:2, 6:4 10. BYE L. ĐERE [3] L. ĐERE [3] Q 11. TOREBKO, PETER BRA P. LORENZI 6:3, 3:6, 6:4 12. LORENZI, PAOLO ITA 5:7, 6:4, 7:6(3) WINNER L. ĐERE [3] PR 13. STEBE, CEDRIK-MARCEL GER J. VESELY 6:4, 6:7(6), 6:3 14. VESELY, JIRI CZE 7:6(5), 3:6, 7:6(2) L. MAYER [8] 15. ANDUJAR, PABLO ESP L. MAYER [8] 3:6, 6:4, 6:4 8 16. MAYER, LEONARDO ARG 6:1, 7:5 D. LAJOVIĆ [4] 5 17. CECCHINATO, MARCO ITA A. BEDENE 7:5, 7:5 6:3, 6:2 18. BEDENE, ALJAŽ SLO A. BEDENE 19. SOUSA, PEDRO POR J. SINNER 7:6(3), 6:3 WC 20. -

Atp Media Information

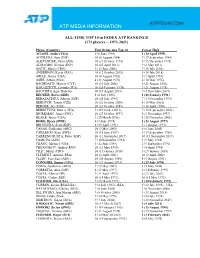

ATP MEDIA INFORMATION ALL-TIME TOP 10 in FEDEX ATP RANKINGS (173 players -- 1973-2021) Player (Country) First Broke into Top 10 Career High AGASSI, Andre (USA) 6 (6 June 1988) 1 (10 April 1995) AGUILERA, Juan (ESP) 10 (6 August 1984) 7 (17 September 1984) ALEXANDER, John (AUS) 10 (21 October 1975) 8 (15 December 1975) ALMAGRO, Nicolas (ESP) 10 (25 April 2011) 9 (2 May 2011) ANCIC, Mario (CRO) 9 (12 June 2006) 7 (10 July 2006) ANDERSON, Kevin (RSA) 10 (12 October 2015) 5 (16 July 2018) ARIAS, Jimmy (USA) 10 (8 August 1983) 5 (9 April 1984) ASHE, Arthur (USA) 4 (23 August 1973) 2 (10 May 1976) BAGHDATIS, Marcos (CYP) 10 (10 July 2006) 8 (21 August 2006) BARAZZUTTI, Corrado (ITA) 10 (20 February 1978) 7 (21 August 1978) BAUTISTA Agut, Roberto 10 (19 August 2019) 9 (4 November 2019) BECKER, Boris (GER) 8 (8 July 1985) 1 (28 January 1991) BERASATEGUI, Alberto (ESP) 10 (25 July 1994) 7 (14 November 1994) BERDYCH, Tomas (CZE) 10 (23 October 2006) 4 (18 May 2015) BERGER, Jay (USA) 10 (23 October 1989) 7 (16 April 1990) BERRETTINI, Matteo (ITA) 9 (28 October 2019) 7 (13 Septemgber 2021) BJORKMAN, Jonas (SWE) 10 (27 October 1997) 4 (3 November 1997) BLAKE, James (USA) 9 (20 March 2006) 4 (20 November 2006) BORG, Bjorn (SWE) 8 (3 June 1974) 1 (23 August 1977) BRUGUERA, Sergi (ESP) 8 (29 April 1991) 3 (1 August 1994) CANAS, Guillermo (ARG) 10 (9 May 2005) 8 (6 June 2005) CARLSSON, Kent (SWE) 10 (15 June 1987) 6 (19 September 1988) CARRENO BUSTA, Pablo (ESP) 10 (11 September 2017) 10 (11 September 2017) CASH, Pat (AUS) 7 (10 September 1984) 4 (9 May -

20-21 Tennis.Indd

Têtes de liste* KEVIN ANDERSON MARCEL GRANOLLERS GRAND PRIX HASSAN II Classement ATP 18 Taille 203 cm Classement ATP 22 Taille 190 cm Afrique du Pays Sud Poids 89 kg Pays Espagne Poids 77 kg 30 ans d’histoire Age 27 Lieu de résidence Delray Beach, Age 27 Lieu de résidence Barcelone, FL, USA Espagne A 1re édition du trophée Date de Naissance 18.05.1986 Début Pro 2007 Date de Naissance 12.04.1986 Début Pro 2003 Hassan II remonte à 1984. Lieu de Naissance Johannesburg Jeu Droitier Lieu de Naissance Barcelone Jeu Droitier Elle comptait déjà avec la Neville Godwin & participation de deux tennis- Coach Michael Anderson Coach Fernando Vicente men marocains, Houcine Saber et Arafa Chekrouni. Le tournoi prendra de l’ampleur dès 1990, avec son BENOIT PAIRE PABLO ANDUJAR inscription au calendrier officiel de l’ATP. Classement ATP 31 Taille 196 cm Classement ATP 35 Taille 180 cm Grâce notamment à la construction du complexe et à une dotation de 125.000 Pays France Poids 80 kg Pays Espagne Poids 76 kg dollars. Il faudra attendre les éditions de Avignon, Valencia Age 24 Lieu de résidence France Age 28 Lieu de résidence Espagne 1992 et 1993 pour que les joueurs marocains Date de Naissance 08.05.1989 Début Pro 2007 Date de Naissance 23.01.1986 commencent à percer, Younes El Aynaoui fait sensation en éliminant une légende du Lieu de Naissance Avignon Jeu Droitier Lieu de Naissance Cuenca Jeu Droitier tennis mondial: l’Autrichien Thomas Coach Lionel Zimbler Coach Jorge Montesinos Muster au 2e tour.