London Assembly Planning and Housing Committee Private/Public Space Investigation Evidence Received Investigation: Private/Public Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riverside Energy Park Design and Access Statement

Riverside Energy Park Design and Access Statement VOLUME NUMBER: PLANNING INSPECTORATE REFERENCE NUMBER: EN010093 DOCUMENT REFERENCE: 07 7. 3 November 2018 Revision 0 APFP Regulation 5(2)(q) Planning Act 2008 | Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 Riverside Energy Park Design and Access Statement - Document Reference 7.3 Harry’s Yard, 176-178 Newhall St, Birmingham, B3 1SJ T: +44 (0)121 454 4171 E:[email protected] Riverside Energy Park Design and Access Statement - Document Reference 7.3 Contents Summary 3.4 Site Analysis 3.4.1 REP Site 1.0 Introduction 3.4.2 Sun Path Analysis 1.1 Introduction 3.4.3 Access 1.1.1 Cory Riverside Energy Holdings Limited 3.4.4 Site Opportunities and Constraints 1.1.2 Riverside Resource Recovery Facility 1.2 Purpose of the Design and Access Statement 4.0 Design Process 4.1 Overview of the Design Process to date 2.0 The Proposed Development 4.2 Good Design Principles 2.1 Overview 2.2 Key Components of the Proposed Development 5.0 Illustrative Masterplan 2.2.1 The Energy Recovery Facility 5.1 Introduction 2.2.2 Anaerobic Digestion Facility 5.2 Illustrative Masterplan Proposals 2.2.3 Solar Photovoltaic Panels 5.2.1 Illustrative Masterplan Proposal 1 - North to South - Stack South 2.2.4 Battery Storage 5.2.2 Illustrative Masterplan Proposal 2 - North to South - Stack North 2.2.5 Other Elements 5.2.3 Illustrative Masterplan Proposal 3 - East to West - Stack West 3.0 Site Overview 5.2.4 Illustrative Masterplan Proposal 4 - East to West - Stack East -

All London Green Grid River Cray and Southern Marshes Area Framework

All River Cray and Southern Marshes London Area Framework Green Grid 5 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 53 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA05 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA05 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . -

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill Carder Bee Bombus Sylvarum in England and Wales

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in England and Wales Editors: Sam Page, Richard Comont, Sinead Lynch, and Vicky Wilkins. Bombus sylvarum, Nashenden Down nature reserve, Rochester (Kent Wildlife Trust) (Photo credit: Dave Watson) Executive summary This report aims to pull together current knowledge of the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in the UK. It is a working document, with a view to this information being reviewed and added when needed (current version updated Oct 2019). Special thanks to the group of experts who have reviewed and commented on earlier versions of this report. Much of the current knowledge on Bombus sylvarum builds on extensive work carried out by the Bumblebee Working Group and Hymettus in the 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, there have been a few key studies such as genetic research by Ellis et al (2006), Stuart Connop’s PhD thesis (2007), and a series of CCW surveys and reports carried out across the Welsh populations between 2000 and 2013. Distribution and abundance Records indicate that the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum was historically widespread across southern England and Welsh lowland and coastal regions, with more localised records in central and northern England. The second half of the 20th Century saw a major range retraction for the species, with a mixed picture post-2000. Metapopulations of B. sylvarum are now limited to five key areas across the UK: In England these are the Thames Estuary and Somerset; in South Wales these are the Gwent Levels, Kenfig–Port Talbot, and south Pembrokeshire. The Thames Estuary and Gwent Levels populations appear to be the largest and most abundant, whereas the Somerset population exists at a very low population density, the Kenfig population is small and restricted. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) Within the Borough

LONDON BOROUGH OF BEXLEY SITES OF IMPORTANCE FOR NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT DECEMBER 2016 Table of contents Bexley sites of importance for nature conservation PART I. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 5 Purpose and format of this document ................................................................................ 5 Bexley context ................................................................................................................... 5 What is biodiversity? ......................................................................................................... 6 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) ....................................................... 6 Strategic green wildlife corridors ....................................................................................... 8 Why has London Borough of Bexley adopted a new SINC assessment? ........................ 10 PART II. Site-by-site review ......................................................................................... 12 Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation ....................................... 13 M015 Lesnes Abbey Woods and Bostall Woods ........................................................... 13 M031 the River Thames and tidal tributaries ................................................................. 15 M041 Erith Marshes ...................................................................................................... 19 M105 -

Bexley Bird Report 2016

Bexley Bird Report 2016 Kingfisher –Crossness – Donna Zimmer Compiled by Ralph Todd June 2017 Bexley Bird Report 2016 Introduction This is, I believe, is the very first annual Bexley Bird Report, it replaces a half yearly report previously produced for the RSPB Bexley Group Newsletter/web-site and Bexley Wildlife web- site. I shall be interested in any feedback to try and measure how useful, informative or welcome it is. I suspect readers will be surprised to read that 153 different species turned up across the Borough during the 12 months of 2016. What is equally impressive is that the species reports are based on just over 13,000 individual records provided by nearly 80 different individuals. Whilst every endeavour has been made to authenticate the records they have not been subject to the rigorous analysis they would by the London Bird Club (LBC) as would normally be the case prior to publication in the annual London Bird Report (LBR). This report has also been produced in advance of the final data being available from LBC as this is not available until mid-summer the following year – it is inevitable therefore that some records might be missing. I am, however, confident no extra species would be added. The purpose of the report is four-fold:- To highlight the extraordinary range of species that reside, breed, pass through/over or make temporary stops in the Borough To hopefully stimulate a greater interest not only in the birds but also the places in which they are found. Bexley Borough has a wide range of open spaces covering a great variety of habitat types. -

Parks, People and Nature

Parks, People and Nature A guide to enhancing natural habitats in London’s parks and green spaces in a changing climate Natural England works for people, places and nature to conserve and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and wildlife in rural, urban, coastal and marine areas. We conserve and enhance the natural environment for its intrinsic value, iithe wellbeing and enjoyment of people, and the economic prosperity it brings. Parks, People and Nature A guide to enhancing natural habitats in London’s parks and green spaces in a changing climate Introduction My vision for London is of a green city, and a fair city, where everyone has access to a high quality green space in which wildlife can be encountered close to where they live and work. London has some of the Ýnest parks of any capital city in the world. Yet it also has some areas lacking in green space, and many more where the quality of the green spaces could be better. This booklet provides a valuable practical guide on how to improve access to nature in parks and green spaces, complimenting my London Plan Implementation Report on Improving LondonersÔ access to nature. Appropriate design and management of our parks and green spaces will be one of the key challenges that will enable the City to adapt to climate change. Park managers need to be working now to plant the trees that will provide shade for a much warmer city in the 2080s. We also need to start thinking now how our parks can help in addressing broader environmental challenges such as Þood risk management. -

Meritas Is Proud to Present Paddington Gardens

A selection of spacious 1, 2, 3 and 4 bedroom apartments and penthouses MARYLEBONE THE LONDON SHARD EYE THE O X F O R D E D G W A R E B O N D CITY STREET ROAD STREET ——— 3 HYDE PARK SERPENTINE PADDINGTON GREEN KNIGHTSBRIDGE PARK Computer generated image. For indicative purposes only. ——— ——— 3 4 Computer generated image. For indicative purposes only. Meritas is proud to present Paddington Gardens An exceptional new residential development in one of central London’s prestigious regeneration areas in Zone 1. Designed by award-winning Assael Architecture and Powell Dobson Architects, Paddington Gardens occupies a 3.8 acre site within London’s most exciting new residential quarter, the Paddington Waterside regeneration. Overlooking beautiful landscaped gardens, the apartments and penthouses feature floor-to-ceiling windows, bespoke kitchens, engineered wooden flooring and a terrace, balcony or winter garden. Paddington Gardens benefits from a host of amenities to enhance the residents’ lifestyle including a 24 hour concierge service and underground car parking. The towers of Paddington Gardens step up in height towards Regent’s Canal, providing elegant proportions and excellent views across London from the upper floors. The elegantly proportioned façades bring together a mix of stone and glazing to provide as much light as possible, with many apartments benefiting from dual aspects. ——— 6 Lifestyle, comfort and convenience A sense of community is essential to the ethos of Paddington Gardens. The central park to the west provides a wonderful communal garden, while the double-height entrance area allows light to flood in. Security is also a key consideration with a 24 hour concierge service, secure underground parking, CCTV and video door entrance system ensuring that Paddington Gardens is always a safe haven. -

Our Future in Place the Report on Consultation

THE FARRELL REVIEW of Architecture + the Built Environment OUR FUTURE IN PLACE THE REPORT ON CONSULTATION BY THE FARRELL REVIEW TEAM Contents P.2 INTRODUCTION P.5 TERMS OF REFERENCE P.6 1. EDUCATION, OUTREACH AND SKILLS P.36 2. DESIGN QUALITY P.66 3. CULTURAL HERITAGE P.83 4. ECONOMIC BENEFITS P.113 5. BUILT ENVIRONMENT POLICY P.120 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE FARRELL REVIEW THE REPORT ON CONSULTATION 1 Introduction This Review has engaged widely from the start. In that respect it set itself apart from many other government reviews and has been independent in both its methods and its means. Over the last year, the team has reached out and consulted with thousands of individuals, groups and institutions. They have been from private, public and voluntary sectors, and from every discipline and practice relating to the built environment: architecture, planning, landscape architecture, engineering, ecology, developers, agents, policymakers, local government and politicians. “We are the editors and curators in the terms of reference that were issued by the of many voices.” Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) Sir Terry Farrell CBE (see page 5). Over 200 responses were received from individuals, companies, groups and This Report on the consultation process by institutions, with many organising questionnaires the Review team, led by Max Farrell and co- for members representing over 370,000 people. ordinated by Charlie Peel, is a structured narrative of the key themes of the Review, told Third were a series of workshops hosted through the many voices of its respondents and around the country. Each of these workshops participants. -

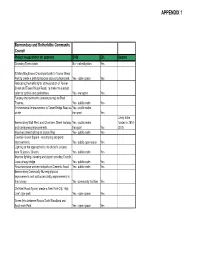

Appendix 1.Pdf

APPENDIX 1 Bermondsey and Rotherhithe Community Council Project suggestions for approval S106 CIL Update Greening Tyers estate No - not mitigation Yes St Mary Magdalene Churchyard path to Tanner Street Park to create a path to improve access to/from park. Yes - open space Yes Relocating the traffic lights at the junction of Tanner Street and Tower Bridge Road, to make the junction safer for cyclists and pedestrians. Yes - transport Yes Footway improvements (uneven paving) to Shad Thames, Yes- public realm Yes Environmental improvements to Tower Bridge Road as Yes - public realm, whole transport Yes Likely to be Bermondsey Wall West and Chambers Street footway Yes - public realm, funded in 2014- and carriageway improvements transport Yes 2015 Improved street lighting on Coxon Way Yes- public realm Yes Fountain Green Square - resurfacing and pond improvements. Yes- public open space Yes Lighting on the approaches to the doctor's surgery near St James' Church Yes- public realm Yes Improve lighting, cleaning and pigeon proofing Crucifix Lane railway bridge Yes- public realm Yes Resurface/pave uneven footpath on Clements Road Yes- public realm Yes Bermondsey Community Nursery physical improvements and add accessibility improvements to the nursery Yes -community facilities Yes Old Kent Road flyover, create a New York City “High Line” style park Yes - open space Yes Green links between Russia Dock Woodland and Southwark Park Yes - open space Yes The old Fish Farm nursery, create a ‘green’ walkway through to Southwark Park from the old Fish Farm -

Derwent London Plc Report & Accounts 2006

Derwent London plc Report & Accounts 2006 Contents 2 Financial highlights 3 Five year review 4 Chairman’s statement 8 Operating review 20 Financial review Financial statements 24 Group income statement 24 Statements of recognised income and expense 25 Balance sheets 26 Group cash flow statement 27 Company cash flow statement 28 Notes to the financial statements 49 Directors’ report 56 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 57 Report on directors’ remuneration 63 Report of the audit committee 64 Report of the nominations committee 65 Independent auditor’s report 67 Directors 68 Five year summary 69 Notice of annual general meeting 71 Financial calendar 71 Advisers Derwent London plc, the company’s new name following the merger of Derwent Valley Holdings plc and London Merchant Securities plc, is a leading central London office specialist with a combined portfolio valued at over £2.5 billion. It is a design-led award-winning property company with a reputation for innovative projects incorporating high quality, contemporary architecture which works closely with leading and emerging architects to create interesting solutions to enhance its schemes. The group invests mainly in the West End but also in those newly improving locations where it perceives future value, bringing quality working environments to its tenants and contributing to London’s regeneration. The board’s strategy is to add value to buildings and sites through creative planning, imaginative design and enterprising lease management. Through this, the aim is to deliver an above -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm.................................................................................................. -

JUN 06 199 O

RESIDENTIAL FABRIC AS MEMORABLE CITY FORM: A Study of West London and Bath by Pradeep Ramesh Dalal Dip. Arch., School of Architecture, CEPT. Ahmedabad, India June, 1987 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE, 1991 @Pradeep Ramesh Dalal 1991. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of the Author Pradeep Dalal, Department of Architecture 10 May, 1991 Certified by ulian Beinart Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Julian Beinart Committee on Graduate Studies MASSACH.USETTS INSTR TE Chairman, Departmental OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 06 199 o Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Both the Library and Archives versions of this thesis (Dalal, Pradeep;1991) contain grayscale images only. This is the best available copy. RESIDENTIAL FABRIC AS MEMORABLE CITY FORM: A Study of West London and Bath by Pradeep Ramesh Dalal Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 15, 1991 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies.