People Elephants and Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KODAGU 571213 Kodagu ST JOSEPHS ASHRAM S4 of 1980.81, VIRAJPET (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found KARNATAKA

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration details Address Sectors working in ST JOSEPHS ASHRAM DEVARAPURA VIRAJPET KODAGU 571213 Kodagu ST JOSEPHS ASHRAM S4 OF 1980.81, VIRAJPET (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found KARNATAKA Agriculture,Art & Culture,Children,Civic Issues,Differently Abled,Disaster Management,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Sharanya Trust Kuvempu extentions Kushalnagara Welfare,HIV/AIDS,Human Rights,Information & Kodagu Sharanya trust 20/2017-18, Kushalnagara (KARNATAKA) Somavarapete taluk Kodagu dist Communication Technology,Panchayati Raj,Rural Development & Poverty Alleviation,Vocational Training,Women's Development & Empowerment,Any Other Differently Abled,Agriculture,Education & MDK-4-00011-2016-17 and MDK116, MADIKERI HEMMATHAL VILLAGE, MAKKANDORR POST, MADIKERI, Kodagu SAADHYA TRUST FOR SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Vocational Training,Women's (KARNATAKA) KODAGU Development & Empowerment Children,Environment & Forests,Human Rights,Rural No 01, Mahila Samaja Building, Napoklu, Kodagu, Karnataka Kodagu PUNASCHETHANA CHARITABLE TRUST IV/2013-14-173, Napoklu (KARNATAKA) Development & Poverty Alleviation,Women's Development & .571214 Empowerment UNIT OF MYSORE ,DIOCESAN EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY, Kodagu Ponnampet Parish Society DRI:RSR:SOS:73/2016-17, Madikeri (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found PONNAMPET, VIRAJPET T G, SOUTH KODAGU MARCARA PARISH SOCIETY ST MICHAELSCHURCH MADIKERI Kodagu MARCARA PARISH SOCIETY 2/73-74, MYSORE (KARNATAKA) Children KODAGU DISTRICT PIN CODE 571201 KARNATAKA Kottamudi, Hodavana Village, Hoddur PO, Madikeri -

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

NOTIFICATION for the POSTS of GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respective R

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE RECTT/50-1/DLGS/2019 Applications are invited by the respective recruiting authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’ against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of GDS Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device, ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the GDS Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same GDS Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM etc.In some of the Branch Post Offices, the BPM has to do all the work of BPM/ABPM. -

Download Itinerary

Starting From Rs. 0 (Per Person twin sharing) PACKAGE NAME : A HOLIDAY TO SERENE SOUTH PRICE INCLUDE Only Breakfast,Welcome Drink,Cab,Sightseeing Day : 1 TRAVEL TO MYSORE & MYSORE SIGHTSEEING Greet and meet on arrival at Bangalore airport and proceed to Mysore, arrival at Mysore, Check into hotel, refresh and later proceed to sightseeing of Mysore include, Chamundeeswri Temple, Brindavan Garden, Sri Ranga Patna. Thippu’s Summer Palace, Mysore Maharaja Palace, Mysore Zoo, Golden Temple, Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary & return back to hotel. Overnight at Mysore SIGHTSEEING Mysore Zoo, Mysore Maharaja Palace, Chamundi Hills, Bandipur National Park, Jagan Mohan Palace, Brindavan Garden, Chamundeshwari Temple, Lalitha Mahal Palace Day : 2 TRAVEL TO COORG & COORG SIGHTSEEING Drive to Coorg. En route, visit Kaveri Nisargadhama and Golden Temple. As soon as you arrive in Coorg, check in at the hotel where overnight stay facilities are arranged. SIGHTSEEING Kaveri Nisargadhama, Golden Buddha Temple Day : 3 COORG SIGHTSEEING After breakfast, visit Dubare Elephant Camp, Abbey Falls, Raja Seat, Madikeri Fort and Mandalpatti View Point by jeep (Jeep cost should be borne by guest) and Omkareshwar Temple. Enjoy your overnight stay at the hotel. SIGHTSEEING Dubare Forest, Abbey Falls, Raja's Seat, Madikeri Fort, Nagarhole National Park Day : 4 VISIT KUKKE & TRAVEL TO UDUPI Morning, visit Kukke Subrahmanya temple, a temple is famous for religious rituals pertaining to snake god, in the temple. First, visit Kashikatte Ganapathi Temple, a very ancient and Ganapathi idol installed by sage Narada and Kukke Shree Abhaya Mahaganapathi, one of the biggest monolithic statues of Ganapathi. It is 21 feet tall and the architecture of the shrine is in Nepali style. -

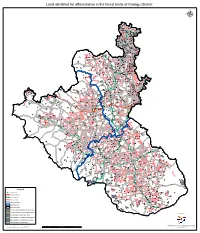

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Kodagu District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Kodagu District µ Hampapura Kesuru Santapura Doddakodi Malaganahalli Kasuru Mavinahalli Hosahalli Janardanahalli Nirgunda KallahalliKodlipet Mollepura Kattepura Nandipura Ramenahalli Ichalapura Ramenahalli Chikkakunda Agali Konginahalli Kattepura Mallahalli Doddakunda Basavanahalli Kudlu Besuru Nilavagilu Urugutti Lakham Kudluru Chikkabandara Bettiganahalli Korgallu Bemballur Hemmane Kiribilaha Talaguru Taluru Doddabilaha Avaredalu Lakkenahalle Siraha Hulukadu Kitturu Harohalli Toyahalli Managali Madare Bageri Dandhalli Hosahalli Bettadahalli Dundalli Mudaravalli Kujageri Kerehalli Hosapura Yedehalli Bellarhalli Kallahalli Sanivarsante Chikanahalli Huluse Gudugalale Sirangala Doddakolaturu Choudenahalli Hemmane Sidagalale Settiganahalli Doddahalli Appasethalli Gangavara Vaderapura Kyatanahalli Gopalpura Kysarahalli Bettadahalli Hittalkeri Nidta Menasa Modagadu Sigemarur Hunsekayihosahalli Mulur Ramenahalli Forest Quarters Mailatapura Mallalli Honnekopal Kurudavalli Nagur Amballi Hattihalli Badabanahalli Nandigunda Kodhalli Nagarahalli Kuti Kundahalli Heggula Bachalli Kanave Basavanahalli Harohalli Bidahalli Kumarhalli Santveri Heggademane Singanhalli Koralalhalli Basavanakoppa Hosagutti Kundahalli Inkalli Dinnehesahalli Tolur Shetthalli Hasahalli Jakhanalli Mangalur Nadenahalli Gaudahalli Malambi Sunti Ajjalli Bettadahalli Doddatolur Kugur Chikkara Santhalli Kogekodi Kantebasavanahalli Gejjihanakodu Chennapuri Alur Honnahalli Siddapura Kudigana Hirikara HitiagaddeKallahalli Sulimolate -

Kodagu District, Karnataka

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KODAGU DISTRICT, KARNATAKA SOMVARPET KODAGU VIRAJPET SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE AUGUST 2007 FOREWORD Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. Central Ground Water Board has decided to bring out district level ground water information booklets highlighting the ground water scenario, its resource potential, quality aspects, recharge – discharge relationship, etc., for all the districts of the country. As part of this, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore, is preparing such booklets for all the 27 districts of Karnataka state, of which six of the districts fall under farmers’ distress category. The Kodagu district Ground Water Information Booklet has been prepared based on the information available and data collected from various state and central government organisations by several hydro-scientists of Central Ground Water Board with utmost care and dedication. This booklet has been prepared by Shri M.A.Farooqi, Assistant Hydrogeologist, under the guidance of Dr. K.Md. Najeeb, Superintending Hydrogeologist, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore. I take this opportunity to congratulate them for the diligent and careful compilation and observation in the form of this booklet, which will certainly serve as a guiding document for further work and help the planners, administrators, hydrogeologists and engineers to plan the water resources management in a better way in the district. Sd/- (T.M.HUNSE) Regional Director KODAGU DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl.No. -

Review of Human-Elephant FINAL Reduced 01.Cdr

Prithiviraj Fernando, M. Ananda Kumar, A. Christy Williams, Eric Wikramanayake, Tariq Aziz, Sameer M. Singh WORLD BANK-WWF ALLIANCE FOR FOREST CONSERVATION & SUSTAINABLE USE Review of Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation Measures Practiced in South Asia (AREAS Technical Support Document Submitted to World Bank) Prithiviraj Fernando, M. Ananda Kumar, A. Christy Williams, Eric Wikramanayake, Tariq Aziz, Sameer M. Singh Published in 2008 by WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © text and graphics: 2008 WWF. All rights reserved. Photographs by authors as credited. CONTENTS Preamble 1-2 LIST OF TECHNIQUES Problem Animal Removal 28-33 Traditional Crop Protection 3-7 Capture and domestication Capture and semi-wild management Crop guarding Elimination Noise and Throwing Things Fire Compensation & Insurance 34-35 Supplements to traditional crop protection Land-Use Planning 36-38 Alarms Providing benefits from conservation to Repellants Local communities Organized Crop Protection 8-11 Recommendations 39 Guard teams, 40-43 Vehicle patrols, References Cited Koonkies Literature Cited 44-45 Elephant Barriers 12-18 Physical FORMAT FOR Wire fences EACH TECHNIQUE Log and stone fences Technique Ditches Applicable scale Biological fences Objective Psychological Description of technique Electric fences Positive effects Cleared boundaries and simple demarcation of fields People Elephants Buffer Crops & Unpalatable Crops 19-20 Negative effects People Supplementary Feeding 21-22 Elephants Translocation 23-27 Future needs Chemical immobilization and transport In-country applications Elephant drives Sri Lanka PREAMBLE ew wild species evoke as much attention and varied emotions from humans as elephants. -

Graduate Student Summer Fieldwork Award Report, October 2019

Institute for Regional and International Studies (IRIS) Graduate Student Summer Fieldwork Award Report, October 2019 Quantifying forest loss in the Nethravathi watershed, India Deepika Guruprasad, Environmental Observation and Informatics Master’s Program Nelson Institute, UW Madison. The Western Ghats is a mountain range which runs parallel to the western coast of India. It is a global biodiversity hotspot which is home to several endangered and endemic mammals, birds and plant species. Many life-sustaining rivers originate here and provide several irreplaceable ecosystem services. The Nethravathi river is one of the major west flowing rivers whose tributaries originate in these mountains. Its watershed has some of the last untouched tropical forests which are key to maintaining connectivity between two protected areas, Kudremukh National Park in the North and Pushpagiri Wildlife sanctuary in the South. In the last 20 years, this region has seen a rapid loss of forests due to ill-planned linear infrastructure projects such as pipelines, roads, hydroelectric, and river diversion dams. These projects have and continue to fragment the landscape as new projects are proposed and implemented with little or no impact assessment. Land use change alters a homogenous landscape into heterogeneous patches, which leads to habitat fragmentation. My summer leadership placement was with the wildlife advocacy non-profit, Wildlife First. The objective of this placement was to map and quantify forest loss due to linear infrastructure projects in the Nethravathi river watershed. Filling in data gaps using reliable land use maps and forest loss statistics is key to make evidence-based policy recommendations. The first part of my project was to map land use of the region using satellite imagery. -

BEDS DETAILS in GOVERNMENT HOSPITALS AS on 05/07/2021 Total Beds Alloted for Covid-19 Occupied Unoccupied S

Government of Karnataka COVID-19 War Room, Mysuru Daily Report COVID-19 Positive Cases Analysis of Mysuru District as on 05/0 7/2021 (as on 07:30 PM) Mysuru District COVID -19 War Room, DC Office, Mysuru Page 1 of 27 Prepared By – District Covid-19 War Room MYSURU DISTRICT COVID WAR ROOM MEDIA BULLETIN DATED : 05-07-2021 Situation till: 6:00 PM Screening of all COVID -19 suspects continues Summary as below: Total number of persons observed to date 815691 Total number of persons who have completed 7 days of isolation 637323 Total number of persons isolated in the home for 7 days 10211 Total 3678 Isolated in Dedicated COVID Government 281 hospital's Private 968 Isolated in Dedicated COVID Government 88 Total active cases Health Care Private 221 Government 462 Isolated in COVID Care Centers Private 0 Isolated in Home 1658 Today's Samples Tested 10903 Total samples Tested Total 1591351 Today's Positive Cases 371 Cumulative Positive's 168157 Today's Discharge 490 Cumulative Discharged 162270 Today's Death 6 Cumulative Death’s 2209 Page 2 of 27 Prepared By – District Covid-19 War Room ANALYSIS AND ANALYTICS OF CORONA POSITIVE PATIENTS IN MYSURU DISTRICT (as on 05.07.2021 at 07:30 PM) Total Cases 168157 Total Recovered 162270 Total Death 2209 New Cases in last 24 371 Hrs Positive Death Sl Positive Active Death cases in TALUK Discharges cases No Cases Cases cases last 24 reported hours 1 H.D.KOTE 5158 4966 131 61 16 0 2 HUNSUR 9393 8985 324 84 50 2 3 K.R.NAGAR 9998 9540 377 81 47 0 4 NANJANGUDU 10630 10238 269 123 12 0 5 PERIYAPATNA 6633 6150 -

Funeral Rites Across Different Cultures

section nine critical incident FUNERAL RITES ACROSS DIFFERENT CULTURES Responses to death and the rituals and beliefs surrounding it tend to vary widely across the world. In all societies, however, the issue of death brings into focus certain fundamental cultural values. The various rituals and ceremonies that are performed are primarily concerned with the explanation, validation and integration of a peoples’ view of the world. In this section, the significance of various symbolic forms of behaviour and practices associated with death are examined before going on to describe the richness and variety of funeral rituals performed according to the tenets of some of the major religions of the world. THE SYMBOLS OF DEATH Social scientists have noted that of all the rites of passage, death is most strongly associated with symbols that express the core life values sacred to a society. Some of the uniformities underlying funeral practices and the symbolic representations of death and mourning in different cultures are examined below: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF COLOUR When viewed from a cross-cultural perspective, colour has been used almost universally to symbolise both the grief and trauma related to death as well as the notion of ‘eternal life’ and ‘vitality’. Black, with its traditional association with gloom and darkness, has been the customary colour of mourning for men and women in Britain since the fourteenth century. However, it is important to note that though there is widespread use of black to represent death, it is not the universal colour of mourning; neither has it always provided the funeral hue even in Western societies. -

Rating Rationale Brickwork Ratings Assigns “BWR-KA-D” (Provisional) for the Tourism – Homestay Rating of the Hillz Homestay, Madikeri, Kodagu District, Karnataka

Rating Rationale Brickwork Ratings assigns “BWR-KA-D” (Provisional) for the Tourism – Homestay Rating of The Hillz Homestay, Madikeri, Kodagu District, Karnataka Brickwork Ratings India Pvt Ltd (BWR) has assigned “BWR-KA-D”#* (Provisional) (Pronounced BWR Karnataka D) Tourism – Homestay rating to The Hillz Homestay, Madikeri, Kodagu District, Karnataka which indicates that the organization provides/delivers Average Quality of Facility. This Provisional Rating is valid for 6 months and will be considered as a regular rating at the discretion of BWR, upon submission of the Original Homestay Registration Certificate issued by the Department of Tourism, Government of Karnataka. HOMESTAY PROFILE: The Hillz Homestay (THH), Madikeri, Kodagu District, Karnataka was established by Mrs. Beebijan and her family. THH is located at #76, Kudige Road, Kudumangalore Village and Post, Kushalnagar - Somwarpet Taluk, Kodagu District, Karnataka. THH is located around 3 Kms from Kushalnagar town and the approach road is motorable. The home stay is built on land area of ~10 cents and the built up area is ~ 6 cents. THH is a budget homestay and suitable for couples, groups and travelers. THH is a new homestay and operations are yet to start. It has 2 rooms on the first floor of the building to accommodate guests. THH is around 3 Kms from Kushalnagar town center, around 91 kms from Mysore and 170 Kms from Mangalore in Karnataka. OPERATIONS, FACILITIES AND SERVICES: The Hillz Homestay (THH) enjoys locational advantages, as it is situated in Madikeri with tourist attractions like Madikeri Fort which is around 2 kms from the home stay and Dubare which is 27 Km from the hometay . -

Mgl-Int-1-2013-Unpaid Shareholders List As on 31

DEMAT ID_FOLIO NAME WARRANT NO MICR DIVIDEND AMOUNT ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 000404 MOHAMMED SHAFEEQ 27 508 30000.00 PUTHIYAVEETIL HOUSE CHENTHRAPPINNI TRICHUR DIST. KERALA DR. ABDUL HAMEED P.A. 002679 NARAYANAN P S 51 532 12000.00 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 89 570 36000.00 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30066910088862 K PHANISRI 116 597 15900.00 Q NO 197A SECTOR I UKKUNAGARAM VISAKHAPATNAM 530032 IN30047640586716 P C MURALEEDHARAN NAIR 120 601 15000.00 DOOR NO 92 U P STAIRS DEVIKALAYA 8TH MAIN RD 9TH CROSS SARASWATHIPURAM MYSORE 570009 001424 BALARAMAN S N 126 607 60000.00 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 002473 GUNASEKARAN V 128 609 30000.00 NO.5/1324,18TH MAIN ROAD ANNA NAGAR WEST CHENNAI 600040 000697 AMALA S. 143 624 12000.00 36 CAR STREET SOWRIPALAYAM COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641028 000953 SELVAN P. 150 631 18000.00 18, DHANALAKSHMI NAGAR AVARAMPALAYAM ROAD, COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641044 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 153 634 60000.00 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 002985 BABY MATHEW 173 654 12000.00 PUTHRUSSERY HOUSE PULIKKAYAM KODANCHERY CALICUT 673580 001680 RAVI P 182 663 30000.00 SUDARSAN CHEMBAKKASSERY TATTAMANGALAM KERALA 678102 001440 RAJI GOPALAN 198 679 60000.00 ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 001756 UNNIKRISHNAN P 222 703 30000.00 'SREE SAILAM' PUDUKULAM ROAD PUTHURKKARA, AYYANTHOLE POST THRISSUR 680003 AMBIKA C P 1201090001296071 REBIN SUNNY 227 708 18750.00 21/14 BEETHEL P O AYYANTHOLE THRISSUR 680003 IN30163741039292 NEENAMMA VINCENT 260 741 18000.00 PLOT NO103 NEHRUNAGAR KURIACHIRA THRISSUR 680006 002191 PRESANNA BABU M V 310 791 30000.00 MURIYANKATTIL HOUSE EDAKULAM IRINJALAKUDA, THRISSUR KERALA 680121 SHAILA BABU 001567 ABUBAKER P B 375 856 15000.00 PUITHIYAVEETIL HOUSE P O KURUMPILAVU THRISSUR KERALA 680564 IN30163741303442 REKHA M P 419 900 20250.00 FLAT NO 571 LUCKY HOME PLAZA NEAR TRIPRAYAR TEMPLE NATTIKA P O THRISSUR 680566 1201090004031286 KUMARAN K K .