Part Three A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Sites and Policies Plan Statement on Issues and Questions

Development Sites and Policies Plan Statement on Issues and Questions Issue 7– Housing Allocations including alternative sites for consideration (DSP40) October 2014 DCD-11 1 7.1 Bearing in mind the legal judgement referred to in my Question 1 to the Council (and the Council’s response), is the Council’s approach towards the identified housing requirement justified and in all other respects sound? 7.1.1 The Council’s approach towards housing requirements for the Borough is set out in paragraphs 5.172 to 5.174 and Table 4 (page 87) of LP2. The requirements for the Borough are separate from Welborne, as explained in the Council’s response to Question 7.2 below. The section of LP2 referred to above explains that the Borough’s housing requirements are established by Policy CS2 of the adopted Core Strategy. This in turn was based on evidence that supported the 2005 South Hampshire Strategy (DPH02) and was taken forward by the Policy SH5 of South East Plan (DOE1). 7.1.2 Paragraph 5.174 of LP2 explains that, since the adoption of the Core Strategy, the South Hampshire Strategy (SHS) was revised to take account of changes in the economy, including the recession (DPH01). The 2012 SHS is not a part of the statutory development plan, but is does represent the currently agreed PUSH position on the apportionment of South Hampshire’s housing requirements (see the Council’s response to Question 7.4 below). The 2012 SHS (DPH01) included revised housing targets for the period to 2026. The effect of this was to increase the Fareham Borough (outside of Welborne) housing target for the period 2011 to 2026 by 472 homes (approximately 31 homes per year). -

Part Two 1914 -1938 Part Two 1914 - 1938

Part Two 1914 -1938 Part Two 1914 - 1938 Childhood and Families Alan Brind My granddad was Herbert Allen (Jack) Laxton 1884 – 1936. He married Eva Whitear from Titchfield in 1913 and they lived at 81 West St. Titchfield. Jack served for 24 years in the 108th Heavy Battery Royal Garrison Artillery which, as Sergeant, he left in 1926. He was a horseman par excellence and served the whole of WW1 in France and Belgium coming through numerous engagements uninjured. He was awarded a Mons Star with Clasp and Roses, British Army War Medal and Victory Medals. He left the army in 1926 and became a bricklayer and worked on the building of Titchfield Primary School and also the Embassy and Savoy cinemas in Fareham. It was ironic that despite having worked with horses throughout his army career, he died, aged 52, following an infection due to a bite from a horse fly. Donald Upshall As I was the first grandchild in the Upshall family I was named after my uncle who was killed in WW1. If you look in the church you will see his name on the remembrance plaque. My father started the garage on East Street when I was born. Now, in 2015, we've been in business 89 years. Today you don't realise how narrow the roads were then. There were no kerbs. You just walked along the edge of the road. But there wasn’t much traffic then. It is so different now of course. I remember the main A27 road. I used to push my brother in his pushchair all the way in to Fareham where they had all these Hornby toys. -

Locks Heath, Sarisbury and Warsash

LOCKS HEATH, SARISBURY AND WARSASH Character Assessment 1 OVERVIEW .....................................................................................................................................2 2 CHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTIONS..............................................................................7 2.1 LSW01 Sarisbury......................................................................................................................7 01a. Sarisbury Green and environs.....................................................................................................7 01b. Sarisbury Green early suburbs....................................................................................................8 2.2 LSW02 Warsash Waterfront .......................................................................................... 12 2.3 LSW03 Park Gate District Centre................................................................................ 14 2.4 LSW04 Locks Heath District Centre........................................................................... 16 2.5 LSW05 Coldeast Hospital................................................................................................. 18 2.6 LSW06 Industrial Estates (Titchfield Park).............................................................. 21 06a. Segensworth East Industrial Estate......................................................................................... 21 06b. Matrix Park .............................................................................................................................. -

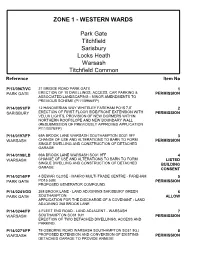

Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No

ZONE 1 - WESTERN WARDS Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No P/14/0321/FP 290 BROOK LANE - BROOK LANE REST HOME - SARISBURY 1 PARK GATE GREEN SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7DP PERMISSION PROPOSED GROUND FLOOR EXTENSION TO REAR TO ALLOW RE-ORGANISATION OF EXISTING ACCOMMODATION AND CIRCULATION SPACE AND THE PROVISION OF THREE ADDITIONAL BEDROOMS. WIDENING OF VEHICULAR ACCESS FROM BROOK LANE AND RE-CONFIGURATION OF CAR PARKING TO PROVIDE THREE ADDITIONAL PARKING SPACES P/14/0340/FP 63 BRIDGE ROAD PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7GG 2 PARK GATE PROPOSED BUILDING OF TWO THREE BEDROOM CHALET PERMISSION BUNGALOWS TO THE REAR OF 63 BRIDGE ROAD USING THE EXISTING SITE ENTRANCE. P/14/0368/FP 1 LOWER CHURCH ROAD FAREHAM HAMPSHIRE PO14 4PW 3 [O] PROPOSED FIRST-FLOOR EXTENSION OVER GARAGE, TO PERMISSION TITCHFIELD ACHIEVE THE PROVISION OF A ONE-BEDROOMED ANNEXE. COMMON P/14/0405/FP 54 BEACON WAY PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7GL 4 PARK GATE PROPOSED FIRST FLOOR SIDE EXTENSION, REAR DORMER PERMISSION WINDOW AND THREE ROOF LIGHTS IN THE FRONT ROOF SLOPE P/14/0415/FP LAND TO THE SOUTH WEST SIDE OF BURRIDGE ROAD 5 SARISBURY BURRIDGE ROAD BURRIDGE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 1BY PERMISSION REDESIGN OF AN EXISTING PITCH, INCLUDING RELOCATION OF THE CARAVANS AND UTILITY/DAY ROOM GRANTED FOR RESIDENTIAL PURPOSES FOR 1 NO GYPSY PITCH WITH THE RETENTION OF THE GRANTED HARD STANDING ANCILLARY TO THAT USE P/14/0429/FP 5 EASTBROOK CLOSE PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7AW 6 [O] FRONT SINGLE STOREY EXTENSION AND ALTERATIONS PERMISSION PARK GATE P/14/0455/FP -

G251 Burridge to Swanwick and Park Gate 27 Taxishare Leaflet

The Burridge to Swanwick and Park Gate 27 Taxishare A public transport service for passengers travelling from Burridge and Curbridge into Swanwick and Park Gate • Bury Farm What is the Burridge to • Curbridge What do I do next? Swanwick and Park Gate • Horse and Jockey Taxishare? • Fairthorne Manor Firstly you must register with Hampshire County Council (this is It is a public transport service for anyone free) by calling the number below. who needs to travel from Burridge and When can I travel? Curbridge into Swanwick and Park Gate. The service operates on Mondays and You will then be sent a membership pack with the booking number to ring The service is similar to a bus service, Fridays at the following times. when you would like to travel. except that passengers will need to Journeys into Swanwick and Park Gate book in advance and the journey will be For more information please call operated by a taxi instead of a bus. Curbridge 0955 Hampshire County Council on Burridge 1000 Where can I travel to? Swanwick rail station 1005 01962 846785 Pre-booked passengers will be dropped Park Gate (Bridge Road 1010 (standard and local call rates apply to this off/picked up at Swanwick rail station or bus stop) number) Park Gate (Bridge Road bus stop). Journeys from Swanwick and Park Gate Where will I be picked up from? Park Gate (Bridge How do I use it? 1205 1405 The Carshare will pick up from the Road bus stop) following bus stops along the line of Swanwick rail station 1210 1410 To use the service you must book your route: Burridge 1215 1415 seat by 4pm the day before you wish Curbridge 1220 1420 to travel. -

Dc-050810-R01-Awe.Doc - 2

Item 6(i) Report to Planning Development Control Committee Date: 10 August 2005 Report of: Chief Development Control Officer Subject: PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND MISCELLANEOUS MATTERS SUMMARY This report recommends action on various planning applications and miscellaneous items RECOMMENDATION The recommendations are detailed individually at the end of the report on each planning application and miscellaneous items. dc-050810-r01-awe.doc - 2 - Index List of Applications with Page Numbers Application Number Item FAREHAM EAST P/05/0857/FP 49 Old Turnpike, Fareham Erection of Detached Dwelling and Garages Permission 13 P/05/0876/FP 1 Fern Cottages, Wickham Road, Fareham Erection of Two Storey Side Extension to Permission 14 form Two Flats. P/05/0881/VC Pook Lane - The Old Stables, Fareham Variation of Condition 6 of P/04/1096/VC(to Permission 15 permit Caravan to be sited within Hay Store for Ancillary use) FAREHAM NORTH P/05/0926/FP Funtley Hill - Funtley Court, Fareham, - Land to Rear of Erection of Building for B1 Business Use Permission 16 FAREHAM SOUTH P/05/0883/FP 99 Gosport Road - Enfield House -, Fareham Erection of Single Storey Rear Extensions, Permission 17 New Generator Compound & Installation of3 Air Conditioning Units P/05/0884/LB 99 Gosport Road - Enfield House -, Fareham Erection of Single Storey Rear Extensions, Listed Building 18 New Generator Compound & Installation of3 Consent Air Conditioning Units P/05/0885/FP 39 Fairfield Avenue, Fareham Erection of Two Storey Side/ Rear Extension Permission 19 to Form Dwelling P/05/0898/FP -

Hamble Lane, Southampton, Hampshire, SO31 4QE

Hamble Lane, Southampton, Hampshire, SO31 4QE LOCATION Contents LOCATION Introduction An invaluable insight into your new home This Location Information brochure offers an informed overview of Hamble Lane as a potential new home, along with essential material about its surrounding area and its local community. It provides a valuable insight for any prospective owner or tenant. We wanted to provide you with information that you can absorb quickly, so we have presented it as visually as possible, making use of maps, icons, tables, graphs and charts. Overall, the brochure contains information about: The Property - including property details, floor plans, room details, photographs and Energy Performance Certificate. Transport - including locations of bus and coach stops, railway stations and ferry ports. Health - including locations, contact details and organisational information on the nearest GPs, pharmacies, hospitals and dentists. Local Policing - including locations, contact details and information about local community policing and the nearest police station, as well as police officers assigned to the area. Education - including locations of infant, primary and secondary schools and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for each key stage. Local Amenities - including locations of local services and facilities - everything from convenience stores to leisure centres, golf courses, theatres and DIY centres. Leaders 1 Freegrounds Road, Hedge End, Southampton, SO30 0HG 01489 899477 LOCATION The Property HAMBLE LANE, SOUTHAMPTON £150,000 x1 x1 -

X4 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X4 bus time schedule & line map X4 Fareham View In Website Mode The X4 bus line (Fareham) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fareham: 6:45 PM - 7:15 PM (2) Fareham: 6:31 PM (3) Locks Heath: 5:41 PM - 6:11 PM (4) Portsmouth: 7:02 AM - 6:15 PM (5) Southampton City Centre: 6:24 AM - 5:11 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X4 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X4 bus arriving. Direction: Fareham X4 bus Time Schedule 63 stops Fareham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:15 PM - 7:15 PM Monday Not Operational Westquay, Southampton City Centre Arundel Bridge, Southampton Tuesday 6:45 PM - 7:15 PM Houndwell Park, Southampton City Centre Wednesday 6:45 PM - 7:15 PM 19 Hanover Buildings, Southampton Thursday 6:45 PM - 7:15 PM East Street, Southampton City Centre Friday 6:45 PM - 7:15 PM Queensway, Southampton Saturday 6:15 PM - 7:15 PM Briton Street, Queens Park Queensway, Southampton Queens Terrace, Queens Park Orchard Place, Southampton X4 bus Info Direction: Fareham College Keep, Queens Park Stops: 63 58 Terminus Terrace, Southampton Trip Duration: 54 min Line Summary: Westquay, Southampton City Centre, Itchen Bridge, Chapel Houndwell Park, Southampton City Centre, East 4 Albert Road South, Southampton Street, Southampton City Centre, Briton Street, Queens Park, Queens Terrace, Queens Park, College Bridge Link Road, Woolston Keep, Queens Park, Itchen Bridge, Chapel, Bridge Cooper's Lane, Southampton Link Road, Woolston, Fort Road, Woolston, St Annes Road, Woolston, The Swan, Woolston, -

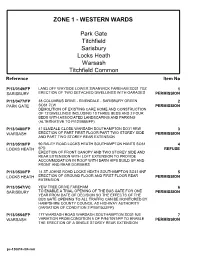

Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No

ZONE 1 - WESTERN WARDS Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No P/13/0967/VC 21 BRIDGE ROAD PARK GATE 1 PARK GATE ERECTION OF 10 DWELLINGS, ACCESS, CAR PARKING & PERMISSION ASSOCIATED LANDSCAPING - MINOR AMENDMENTS TO PREVIOUS SCHEME (P/11/0966/FP) P/14/0051/FP 12 HANOVERIAN WAY WHITELEY FAREHAM PO15 7JT 2 SARISBURY ERECTION OF FIRST FLOOR SIDE/FRONT EXTENSION WITH PERMISSION VELUX LIGHTS, PROVISION OF NEW DORMERS WITHIN NORTHERN ROOFSLOPE AND NEW BOUNDARY WALL (RESUBMISSION OF PREVIOUSLY APPROVED APPLICATION P/11/0078/FP) P/14/0197/FP 69A BROOK LANE WARSASH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 9FF 3 WARSASH CHANGE OF USE AND ALTERATIONS TO BARN TO FORM PERMISSION SINGLE DWELLING AND CONSTRUCTION OF DETACHED GARAGE P/14/0198/LB 69A BROOK LANE WARSASH SO31 9FF 4 WARSASH CHANGE OF USE AND ALTERATIONS TO BARN TO FORM LISTED SINGLE DWELLING AND CONSTRUCTION OF DETACHED BUILDING GARAGE CONSENT P/14/0214/FP 4 DEWAR CLOSE - MAKRO MULTI-TRADE CENTRE - FAREHAM 5 PARK GATE PO15 5UB PERMISSION PROPOSED GENERATOR COMPOUND P/14/0241/OD 268 BROOK LANE - LAND ADJOINING SARISBURY GREEN 6 PARK GATE SOUTHAMPTON ALLOW APPLICATION FOR THE DISCHARGE OF A COVENANT - LAND ADJOINING 268 BROOK LANE P/14/0244/FP 3 FLEET END ROAD - LAND ADJACENT - WARSASH 7 WARSASH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 9JH PERMISSION ERECTION OF TWO DETACHED DWELLINGS, ACCESS AND PARKING. P/14/0271/FP 79 OSBORNE ROAD WARSASH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 9GJ 8 WARSASH PROPOSED EXTENSION AND CONVERSION OF EXISTING PERMISSION DETACHED GARAGE TO PROVIDE ANNEXE P/14/0321/FP 290 BROOK LANE - BROOK LANE REST HOME - SARISBURY 9 PARK GATE GREEN SOUTHAMPTON SO31 7DP REFUSE PROPOSED GROUND FLOOR AND FIRST FLOOR EXTENSIONS TO REAR TO ALLOW RE-ORGANISATION OF EXISTING ACCOMMODATION AND CIRCULATION SPACE AND THE PROVISION OF 5NO ADDITIONAL BEDROOMS. -

Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No

ZONE 1 - WESTERN WARDS Park Gate Titchfield Sarisbury Locks Heath Warsash Titchfield Common Reference Item No P/13/0149/FP LAND OFF WAYSIDE LOWER SWANWICK FAREHAM SO31 7GZ 1 SARISBURY ERECTION OF TWO DETACHED DWELLINGS WITH GARAGES PERMISSION P/13/0477/FP 38 COLUMBUS DRIVE - RIVENDALE - SARISBURY GREEN 2 PARK GATE SO31 7LW PERMISSION DEMOLITION OF EXISTING CARE HOME AND CONSTRUCTION OF 12 DWELLINGS INCLUDING 10 THREE BEDS AND 2 FOUR BEDS WITH ASSOCIATED LANDSCAPING AND PARKING (ALTERNATIVE TO P/12/0885/FP) P/13/0480/FP 41 ELMDALE CLOSE WARSASH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 9RW 3 WARSASH ERECTION OF PART FIRST FLOOR PART TWO STOREY SIDE PERMISSION AND PART TWO STOREY REAR EXTENSION P/13/0519/FP 90 RALEY ROAD LOCKS HEATH SOUTHAMPTON HANTS SO31 4 LOCKS HEATH 6PD REFUSE ERECTION OF FRONT CANOPY AND TWO STOREY SIDE AND REAR EXTENSION WITH LOFT EXTENSION TO PROVIDE ACCOMMODATION IN ROOF WITH BARN HIPS BUILD UP AND FRONT AND REAR DORMERS P/13/0530/FP 14 ST JOHNS ROAD LOCKS HEATH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 6NF 5 LOCKS HEATH ERECTION OF GROUND FLOOR AND FIRST FLOOR REAR PERMISSION EXTENSION P/13/0547/VC YEW TREE DRIVE FAREHAM 6 SARISBURY TO ENABLE A TRIAL OPENING OF THE BUS GATE FOR ONE PERMISSION YEAR FROM DATE OF DECISION SO THE EFFECTS OF THE BUS GATE OPENING TO ALL TRAFFIC CAN BE MONITORED BY HAMPSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL AS HIGHWAY AUTHORITY (VARIATION OF CONDITION 2 P/05/1533/FP) P/13/0554/FP 177 WARSASH ROAD WARSASH SOUTHAMPTON SO31 9JE 7 WARSASH VARIATION FROM CONDITION 5 OF P/94/1051/FP TO ENABLE PERMISSION THE ERECTION OF A SINGLE STOREY REAR EXTENSION pc-130814-r04-lsm P/13/0588/FR 10 LOCKS ROAD LOCKS HEATH SOUTHAMPTON HANTS SO31 8 LOCKS HEATH 6NT PERMISSION ERECTION OF 4 BEDROOMED DETACHED DWELLING WITH INTEGRAL GARAGE AND 3 PARKING SPACES ON LAND ADJACENT TO EXISTING DWELLING (FULL RENEWAL OF P/10/0492/FP) pc-130814-r04-lsm pc-130814-r04-lsm. -

Portsmouth X4 Southampton

Southampton - Locks Heath - Fareham - Portsmouth X4 via Woolston - Lowford - Sarisbury Green - Park Gate - Titchfield - Portchester Southampton - Locks Heath - Fareham - Gosport X5 via Woolston - Lowford - Sarisbury Green - Warsash - Titchfield - Stubbington - Lee-on-the-Solent Daily from Sunday 12 April 2020 Service Number X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 X4 X5 Southampton, West Quay 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 1445 1515 1545 1615 1645 1715 1745 Bridge Link Road 0722 0752 0822 0852 0922 0952 1022 1052 1122 1152 1222 1252 1322 1352 1422 1452 1522 1552 1622 1652 1722 1752 Sholing, Botley Road 0729 0759 0829 0859 0929 0959 1029 1059 1129 1159 1229 1259 1329 1359 1429 1459 1529 1559 1629 1659 1729 1759 Bursledon, Dodwell Lane 0737 0807 0837 0907 0937 1007 1037 1107 1137 1207 1237 1307 1337 1407 1437 1507 1537 1607 1637 1707 1737 1807 Warsash Village .... 0817 .... 0917 .... 1017 .... 1117 .... 1217 .... 1317 .... 1417 .... 1517 .... 1617 .... 1717 .... 1817 Park Gate 0745 .... 0845 .... 0945 .... 1045 .... 1145 .... 1245 .... 1345 .... 1445 .... 1545 .... 1645 .... 1745 .... Locks Heath Centre 0748 0824 0848 0924 0948 1024 1048 1124 1148 1224 1248 1324 1348 1424 1448 1524 1548 1624 1648 1724 1748 1824 Clarendon Crescent 0753 .... 0853 .... 0953 .... 1053 .... 1153 .... 1253 .... 1353 .... 1453 .... 1553 .... 1653 .... 1753 .... Titchfield, Coach Hill 0759 .... 0859 .... 0959 .... 1059 .... 1159 .... 1259 .... 1359 .... 1459 .... 1559 .... 1659 .... 1759 .... Titchfield Bypass .... 0832 .... 0932 .... 1032 .... 1132 .... 1232 .... 1332 .... 1432 .... 1532 .... 1632 .... 1732 .... 1832 Fareham Bus Station 0809 0841 0909 0941 1009 1041 1109 1141 1209 1241 1309 1341 1409 1441 1509 1541 1609 1641 1709 1741 1809 1841 Fareham Bus Station 0811 0843 0911 0943 1011 1043 1111 1143 1211 1243 1311 1343 1411 1443 1511 1543 1611 1643 1711 1743 1811 1843 Fareham College ... -

Park Gate Intouch Summer 2020

CONSERVATIVES – Over two decades of outstanding civic service PARK GATEI &n PRIORYT PARKouch – Summer 2020 Volunteers answer the call just as they did 80 years ago UNLESS you are in your Borough and it is right that your 80s you will have expe- Council should express thanks rienced nothing like it in to them all.” your lifetime. It was a privilege to add his sig- In summer 1940, the RAF nature to Mayor Pamela Bryant’s fought almost down to the last on hundreds of letters thanking Spitfire and Hurricane to drive all the Fareham volunteers who the Luftwaffe from our skies. stepped up through the CO- Eighty years on another Battle VID-19 pandemic to help their of Britain began, only this time community. the outcome against an unseen They include Acts Of Kindness enemy is not yet in our sights. Community (Solent), Waypoint But the national spirit that led Church, Citizens Advice Fare- us to victory through the dark ham, AFC Portchester, One days of World War 2 surfaced Acts of Kindness volunteers are using one of the business hangars Community and Portchester again when an army of volun- at Solent Airport@Daedalus provided free by the Council. Community Association. teers and professionals answered their country’s call. If you know of any unsung heroes we may have missed, we’d Fareham Council Leader Seán Woodward summed up local re- like their names and a brief description of their efforts. action: “We have lived through very difficult and unprecedented You can get a nomination form at www.fareham.gov.uk/than- times.