Perceptions of the Causes of the Troubles in Northern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Publications

Publications National Newspapers Evening Echo Irish Examiner Sunday Business Post Evening Herald Irish Field Sunday Independent Farmers Journal Irish Independent Sunday World Irish Daily Star Irish Times Regional Newspapers Anglo Celt Galway City Tribune Nenagh Guardian Athlone Topic Gorey Echo New Ross Echo Ballyfermot Echo Gorey Guardian New Ross Standard Bray People Inish Times Offaly Express Carlow Nationalist Inishowen Independent Offaly Independent Carlow People Kerryman Offaly Topic Clare Champion Kerry’s Eye Roscommon Herald Clondalkin Echo Kildare Nationalist Sligo Champion Connacht Tribune Kildare Post Sligo Weekender Connaught Telegraph Kilkenny People South Tipp Today Corkman Laois Nationalist Southern Star Donegal Democrat Leinster Express Tallaght Echo Donegal News Leinster Leader The Argus Donegal on Sunday Leitrim Observer The Avondhu Donegal People’s Press Letterkenny Post The Carrigdhoun Donegal Post Liffey Champion The Nationalist Drogheda Independent Limerick Chronnicle Tipperary Star Dublin Gazette - City Limerick Leader Tuam Herald Dublin Gazette - North Longford Leader Tullamore Tribune Dublin Gazette - South Lucan Echo Waterford News & Star Dublin Gazette - West Lucan Echo Western People Dundalk Democrat Marine Times Westmeath Examiner Dungarvan Leader Mayo News Westmeath Independent Dungarvan Observer Meath Chronnicle Westmeath Topic Enniscorthy Echo Meath Topic Wexford Echo Enniscorthy Guardian Midland Tribune Wexford People Fingal Independent Munster Express Wicklow People Finn Valley Post Munster Express Magazines -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

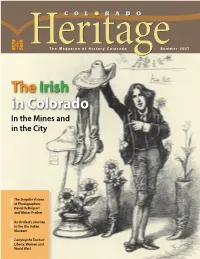

Theirish in Colorado

The Magazine of History Colorado Summer 2017 The Irish in Colorado In the Mines and in the City The Singular Visions of Photographers David DeHarport and Winter Prather An Artifact’s Journey to the Ute Indian Museum Carrying the Torch of Liberty: Women and World War I Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Austin Pride Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Summer 2017 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services 4 The Orange and the Green Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by Ireland’s Great Famine spurred immigration to the History Colorado, contains articles of broad general United States, including the mining camps of Colorado. and educational interest that link the present to the By Lindsey Flewelling past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when 16 Denver’s Irish Resist Nativism submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications The Irish made their mark on Denver’s civic and religious life— office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the and faced waves of organized intolerance. Publications office. History Colorado disclaims By Phylis Cancilla Martinelli responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, The Beautiful, Unphotogenic Country 24 and exhibition listings. Two twentieth-century photographers aimed their lenses at less- considered aspects of Colorado. Postage paid at Denver, Colorado By Adrienne Evans All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

A Aire, a Ambasadóirí, Your Excellencies, a Cháirde, Is Mór an Pléisiúir Dom a Bheith Anseo Inniu Sa Cheantar Álainn

A Aire, A Ambasadóirí, Your Excellencies, A Cháirde, Is mór an pléisiúir dom a bheith anseo inniu sa cheantar álainn, stairiúil seo de Chontae Ciarraí. Mar Uachtarán na hEireann, tá áthas orm an deis seo a thapú chun an méid a rinne Ruairí Mac Easmainn ar son saoirse mhuintir na hÉireann agus ar son cosmhuintir an domhain i gcoitinne a athaint agus a cheiliúradh. [It is my great pleasure to be here today, at this beautiful and historic part of County Kerry. As President of Ireland, I am very happy to have this occasion to acknowledge and celebrate, in the name of the Irish people, the great contribution of Roger Casement, not only to Irish Freedom, but to the universal struggle for justice and human dignity.] Roger Casement was not just a great Irish patriot, he was also one of the great humanitarians of the early 20th century - a man who is remembered fondly by so many people across the world for his courageous work in exposing the darkness that lay at the heart of European imperialism. His remarkable life has attracted the attention of so many international scholars, Peruvian Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa is a recent example, and all of us who are interested in Roger Casement's life are especially indebted to the fine work of Angus Mitchell, in particular for the scholarly work on the Putumayo Diaries, and the recently published "One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diaries of Roger Casement 1914-1916". In his own time, few figures attracted the sympathy and admiration of their contemporaries as widely as Roger Casement. -

“Our Own Boy”: How Two Irish Newspapers Covered The

“OUR OWN BOY”: HOW TWO IRISH NEWSPAPERS COVERED THE 1960 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY by DAVE FERMAN Bachelor of Arts in Communication, 1985 The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Communication Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE MAY 2007 Copyright 2007 by Dave Ferman All rights reserved “OUR OWN BOY” HOW TWO IRISH NEWSPAPERS COVERED THE 1960 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY Thesis approved: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Major Professor ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Graduate Studies Representative ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- For the College of Communication ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. John Tisdale, for his insight and good humor. Enormous thanks also go to Tommy Thomason, Ed.D., and Dr. Karen Steele, who were also on my thesis committee, as well as Dr. Beverly Horvit for her guidance and patience. At the Mary Couts Burnett Library, Joyce Martindale and Sandy Schrag went out of their way to help me acquire the material needed for my research. In Ireland, Lisa McDonagh did the Gaelic translation, Dr. Colum Kenny at Dublin City University made a number of helpful suggestions, Mary Murray was a constant source of support, and the Colohans of Ballymana have given me a second home for more than 20 years and the inspiration to complete this project. I would also like to thank Tamlyn Rae Wright, Kathryn Kincaid, Carol Nuckols, Doug Boggs, Cathy Frisinger, Beth Krugler, Robyn Shepheard, Dorothy Pier, Wayne Lee Gay, my sister Kathy Ferman and Dr. Michael Phillips of the University of Texas at Austin for their support. -

Celebrating 21 Years

Celebrating 21 Years A NATIONALIST SUPPLEMENT | November � ������� ������������������������������������� 1993 2014 Celebrating 21 Years Message from Turlough O’Brien, contents CEO of Tinteán PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, Tinteán was established in 1993 and is now associations TURLOUGH O’BRIEN an important provider of social housing within have provided a the county. We take pride in the standard of quarter of all new housing we provide for our tenants. We are also social housing. PAGE 3 TINTEÁN’S HISTORY, FUNDING AND HOUSING proud of the relationships we have developed Social housing POLICIES with our partners, our tenants and the wider makes up 10% community including Carlow local authorities, of all housing Delta, Irish Council for Social Housing and the in Ireland. 500 PAGE 4 TINTEÁN TENANT PROFILES Department of Environment, Community and housing associations provide 27,000 housing Local Government. tenancies. PAGE 5 “TINTEÁN GIVES HELP TO THOSE WHO NEED Beginning with one scheme for the elderly We operate as efficiently and effectively as IT MOST” - TINTEÁN CHAIRPERSON - EILEEN in our community, Tinteán has addressed the possible and aim to ensure that our financial housing needs of those in most need and those stewardship is of the highest standard. BROPHY with special needs to a very high standard. We work with partners who share a similar The provision of a large number of homes for mission and apply corporate instruments such PAGE 6 TINTEÁN MILESTONES people with special needs is a particular source as private finance to respond creatively and of pride. Tinteán effectively to the huge demand for provides afford- Looking ahead, social housing in Ireland. -

Hibernians Welcome Irish Ambassador Anderson Freedom for All Ireland

DATED MATERIAL DATED ® —HIS EMINENCE, PATRICK CARDINAL O’DONNELL of Ireland Vol. LXXX No. 5 USPS 373340 September-October 2013 1.50 Hibernians Welcome Irish Ambassador Anderson In This Issue… Celebrating Irish Culture in New York AOH and LAOH National and District of Columbia State Board Presidents welcome Ambassador Anne Anderson to Washington, DC, from left, Brendan Moore, Ambassador Anderson, Maureen Shelton, Gail Dapolito (DC LAOH State Board President), and Ralph D. Day (DC AOH State Board President). Page 23 At a formal dinner held at the prestigious National Press Club addressed the DC Convention earlier that day. Also joining the AOH Deputy Consul General located near the White House, the Washington DC State Board at the dinner were numerous DC Irish organizations and former Peter Ryan closed out their biennial convention with a special welcome to Congressman Bruce Morrison and his wife as well as Norman Ireland’s new Ambassador to the United States, Anne Anderson. Houston, director of the Northern Ireland Bureau. Newly re-elected presidents Ralph Day of the DC AOH and Gail The evening’s master of ceremonies was past-National Director Gorman Dapolito of the DC LAOH were honored to be joined at the Keith Carney who kept the busy program running, but also took the head table by Ambassador Anderson and her guest, Dr. Lowe, DC solemn time to read the names of the 32 AOH Brothers and Sisters Chaplain Father John Hurley, our National Presidents Brendan who perished on 9/11 trying to save others (as the 12th anniversary Moore and Maureen Shelton, as well as the president of the National of that tragic day was upcoming at the time of the dinner). -

The Catholic Church and Social Policy160

6. The Catholic Church and Social Policy160 Tony Fahey Introduction The influence of the Catholic Church on social policy in Ireland can be identified under two broad headings — a teaching influence derived from Catholic social thought and a practical influence which arose from the church’s role as a major provider of social services. Historically, the second of these was the more important. The church developed a large practical role in the social services before it evolved anything approaching a formal body of social teaching, and its formal teaching in the social field never matched the inventiveness or impact of its social provision. Today, this order is being reversed. The church’s role as service provider is dwindling, mainly because falling vocations have left it without the personnel to sustain that role. Its reputation as a service provider has also been tarnished by the revelations of shocking abuses perpetrated by Catholic clergy and religious on vulnerable people (particularly children) placed in their care in the past (see, e,g, the Ferns Report – Murphy, Buckley and Joyce, 2005; also O’Raftery and O’Sullivan 2001). Nevertheless, its teaching role in the social field is finding new content and new forms of expression. Despite the corrosive effect of the scandals of the past decade on the church’s teaching authority, these new means of influencing social policy debate have considerable potency and may well offer a means by which the church can play an important part in the development of social policy in the future. 160 This a slightly revised version of a chapter previously published in Seán Healy and Brigid Reynolds (eds.) Social Policy in Ireland. -

Remembering 1916

Remembering 1916 – the Contents challenges for today¬ Preface by Deirdre Mac Bride In the current decade of centenary anniversaries of events of the period 1912-23 one year that rests firmly in the folk memory of communities across Ireland, north and south, is 1916. For republicans this is the year of the Easter Rising which led ultimately to the establishment of an independent THE LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT: THE CHALLENGES republic. For unionists 1916 is remembered as the year of the Battle of the Somme in the First World AND COMPLEXITIES OF COMMEMORATION War when many Ulstermen and Irishmen died in the trenches in France in one of the bloodiest periods of the war. Ronan Fanning,”Cutting Off One's Head to Get Rid of a Headache”: the Impact of the Great War on the Irish Policy of the British Government How we commemorate these events in a contested and post conflict society will have an important How World War I Changed Everything in Ireland bearing on how we go forward into the future. In order to assist in this process a conference was organised by the Community Relations Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund. Entitled Éamon Phoenix, Challenging nationalist stereotypes of 1916 ‘Remembering 1916: Challenges for Today’ the conference included among its guest speakers eminent academics, historians and commentators on the period who examined the challenges, risks Northern Nationalism, the Great War and the 1916 Rising, 1912-1921 and complexities of commemoration. Philip Orr, The Battle of the Somme and the Unionist Journey The conference was held on Monday 25 November 2013 at the MAC in Belfast and was chaired by Remembering the Somme BBC journalist and presenter William Crawley. -

Girls and First Holy Communion in Twentieth-Century Ireland (C

religions Article Fashion and Faith: Girls and First Holy Communion in Twentieth-Century Ireland (c. 1920–1970) Cara Delay Department of History, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC 29424, USA; [email protected] Abstract: With a focus on clothing, bodies, and emotions, this article examines girls’ First Holy Communions in twentieth-century Ireland (c. 1920–1970), demonstrating that Irish girls, even at an early age, embraced opportunities to become both the center of attention and central faith actors in their religious communities through the ritual of Communion. A careful study of First Holy Commu- nion, including clothing, reveals the importance of the ritual. The occasion was indicative of much related to Catholic devotional life from independence through Vatican II, including the intersections of popular religion and consumerism, the feminization of devotion, the centrality of the body in Catholicism, and the role that religion played in forming and maintaining family ties, including cross-generational links. First Communion, and especially the material items that accompanied it, initiated Irish girls into a feminized devotional world managed by women and especially mothers. It taught them that purchasing, hospitality, and gift-giving were central responsibilities of adult Catholic women even as it affirmed the bonds between women family members who helped girls prepare for the occasion. Keywords: girls; women; gender; First Communion; clothing; feminization; family Citation: Delay, Cara. 2021. Fashion and Faith: Girls and First Holy 1. Introduction Communion in Twentieth-Century The Catholic First Holy Communion dress is recognized as an Irish cultural icon. Ireland (c. 1920–1970). Religions 12: In late 2012, the Irish Times and National Museum of Ireland declared it to be one of the 518.