RISING NATIONALISM a Potential Threat to Hong Kong’S Freedom of Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernest Yang Roden Tong

二零一四年四月 APRIL 2014 HK$280 h k - l a w y e r . org Cover Story 封面專題 Face to Face With 專 訪 Ernest Yang Partner, DLA Piper Hong Kong and Shanghai Member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference A PRIL 2014 楊大明律師 歐華律師事務所香港區合夥人兼上海市政協委員 Roden Tong Assistant Vice President, Regional Specialty Claims Manager, Greater China Chubb Group of Insurance Companies 湯文龍律師 助理副總裁, 丘博保險集團大中華區區域理賠經理 REFORM 改 革 COMPANIES 公 司 ON CHINA 中國實務 Report on Excepted Offences under The New Companies Ordinance – Power to the people? Schedule 3 of the Criminal Procedure Highlights of Some Major Changes What’s next for environmental class- Ordinance (Cap 221) (Part 2 - a Companies Registry series) action litigation in China? 《刑事訴訟程序條例》(第221章) 新公司條例 –主要改變概要 權力歸與民眾﹖ 附表3所列的例外罪行報告書 (第二部分–公司註冊處系列) 中國環境公害集體訴訟接著該如何﹖ HONG KONG REUTERS/Gary Hershorn MEDIATION HANDBOOK SECOND EDITION EARLY BIRD OFFER BUY BEFORE 30 MAY 2014 AND SAVE HK$200 An essential handbook about Mediation in Hong Kong for practitioners, business professionals, in-house counsel as well as all others who are interested in Mediation matters in Hong Kong “No other legal development in Hong Kong in recent years has attracted so much widespread interest... as ISBN: 9789626614082 mediation. This handbook is the only one to deal with Pub Date: May 2014 such an important topic in such depth and breadth … Format: Hardback the provisions of real cases and examples are particularly List Price: HK$2,000 illuminating … [an] excellent work”. Early Bird Price: HK$1,800 Mr Huen Wong JP, Currently on the Board -

D6272 2015 年第39 期憲報第4 號特別

D6272 2015 年第 39 期憲報第 4 號特別副刊 S. S. NO. 4 TO GAZETTE NO. 39/2015 G.N. (S.) 57 of 2015 BOOKS REGISTRATION ORDINANCE (CHAPTER 142) A CATALOGUE OF BOOKS PRINTED IN HONG KONG 3RD QUARTER 2014 (Edited by Books Registration Office, Hong Kong Public Libraries, Leisure and Cultural Services Department) This catalogue lists publications which have been deposited with the Books Registration Office during the third quarter of 2014 in accordance with the above Ordinance. These include:— (1) Books published or printed in Hong Kong and have been deposited with the Books Registration Office during this quarter. Publications by the Government Logistics Department, other than separate bills, ordinances, regulations, leaflets, loose-sheets and posters are included; and (2) First issue of periodicals published or printed in Hong Kong during this quarter. Details of their subsequent issues and related information can be found at the fourth quarter. (Please refer to paragraph 3 below) The number in brackets at the bottom right-hand corner of each entry represents the order of deposit of the book during the year, whereas the serial number at the top left-hand corner of each entry is purely an ordering device, linking the annual cumulated author index with the main body of the catalogue. In the fourth quarter, in addition to the list of publications deposited with the Books Registration Office during that quarter, the catalogue also includes the following information for the year:— (1) Chinese and English Author Index; (2) Publishers’ Names and Addresses; (3) Printers’ Names and Addresses; and (4) Chinese and English Periodicals Received;- their title, frequency, price and publisher. -

Bristol Pair Jailed for Laundering Brothel Proceeds

Bristol pair jailed for laundering brothel proceeds - 23 December 2013 http://www.bristolpost.co.uk/Pair-jailed-laundering-proceeds-city- brothels/story-20356666-detail/story.html Khodorkovsky freed after Putin pardon - 20 December 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-25460427 Money laundering escort fraudster ordered to repay £100,000 - 20 December 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-suffolk-25460880 Final prison sentence in Zetas cartel money laundering trials - 18 December 2013 http://www.statesman.com/news/news/crime-law/last-defendant-in- zetas-money-laundering-case-gets/ncNzp/ Two men charged with fraud and money laundering over States of Guernsey £2.6 million fraud - 18 December 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-guernsey-25418718 Melbourne financial adviser jailed for laundering drug money through casinos - 16 December 2013 http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/financial-adviser-jailed-for- laundering-drug-money-20131216-2zgj7.html RBS fined US$100 million by US regulators for sanctions violations - 11 December 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-25341882 Ex-Goldman Sachs banker jailed for money laundering in Ibori case - 9 December 2013 http://in.reuters.com/article/2013/12/09/britain-banker-corruption- idINL6N0JO31920131209 Indonesian former politician jailed for 16 years for corruption and money laundering - 9 December 2013 http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/12/10/former-pks-boss- gets-16-years-graft.html Curtis Warren to get ten more years in prison for failing to return £198 million laundered money -

Chinese Ownerships in European Football: the Example of the Suning Holdings Group

1 Department of Business and Management Chair of Corporate Strategies Chinese ownerships in European football: the example of the Suning Holdings Group SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Prof. Paolo Boccardelli Davide Fabrizio Matr. 668151 CORRELATOR Prof. Enzo Peruffo ACADEMIC YEAR 2018/2019 2 3 Index Introduction ....................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Chinese Ownerships in Football ................................................... 10 1.1 The economic and legal background: revenues diversification and Financial Fair Play ......................................................................................... 11 1.1.1 A mountain to climb: profits drivers in football............................. 11 1.1.2 UEFA and Financial Fair Play: the end of football patronage? ...... 16 1.2 A new Silk Road: brief history of the phenomenon .............................. 21 1.2.1 The internal expansion: State Council’s guidelines and the development of Chinese football ..................................................................................... 21 1.2.2 The external expansion: some very good (and a few, very bad) examples .................................................................................................... 29 1.2.2.1 A.C. Pavia and A.C. Milan.............................................................. 40 1.3 Strategies change: Chinese capital control policies and their aftermaths on football ..................................................................................................... -

Sport in Asia: Globalization, Glocalization, Asianization

7 Sport in Asia: Globalization, Glocalization, Asianization Peter Horton James Cook University, Townsville Australia 1. Introduction Sport is now a truly global cultural institution, one that is no longer the preserve of occidental culture or dominated and organized by Western nations, the growing presence and power of non-occidental culture and individual nations now makes it a truly globalized product and commodity. The insatiable appetite for sport of the enormous Asian markets is redirecting the global flow of sport, with the wider Asia Pacific region now providing massive new audiences for televised sports as the economies of the region continue their growth. This chapter will consider the process of sport’s development in the Asian and the wider Asia Pacific context through the latter phases of the global sportization process (Maguire, 1999). As the locus of the centre of gravity of global geopolitical power is shifting to the Asia Pacific region away from the Euro-Atlantic region the hegemonic sports are now assuming a far more cosmopolitan character and are being reshaped by Asian influences. This has been witnessed in the major football leagues in Europe, particularly the English Premier League and is manifest in the Indian Premier League cricket competition, which has spectacularly changed the face of cricket world-wide through what could be called its ‘Bollywoodization’(Rajadhyaskha, 2003). Perhaps this reflects ‘advanced’ sportization (Maguire, 1999) with the process going beyond the fifth global sportization phase in sport’s second globalization with ‘Asianization’ becoming a major cultural element vying with the previously dominant cultural traditions of Westernization and Americanization? This notion will be discussed in this paper by looking at Asia’s impact on the development of sport, through the three related lenses of: sportization; the global sports formation and, the global media-sport comple. -

José-Antonio Maurellet SC BA Jurisprudence (Law), University of Oxford (St

Des Voeux Chambers 38/F Gloucester Tower The Landmark Central, Hong Kong Telephone: 2526-3071 José-Antonio Maurellet SC BA Jurisprudence (Law), University of Oxford (St. Edmund Hall) (1999) PCLL, University of Hong Kong (2000) Email Address: [email protected] Year Of Call: 2000 (Hong Kong) 2016 (Hong Kong Inner Bar) British Virgin Islands Circuit of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, Solicitor (non practising) Law Society of England & Wales (non practising) Singapore International Commercial Court, Registered Foreign Lawyer Astana International Financial Centre Court (rights of audience) Practice Areas: Arbitration, Mediation, Commercial Law, Company Law and Insolvency, Employment and Anti- Discrimination, Securities Law, Professional Negligence José-Antonio Maurellet S.C. is a Hong Kong born Eurasian. He is an English, Cantonese and French native speaker. He also can speak some Mandarin. Jose read law at St Edmund Hall, Oxford University. He was called to the Hong Kong Bar in 2000 and to the Inner Bar in 2016. He was admitted in 2020 as a solicitor of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, British Virgin Islands circuit. He is also a registered foreign lawyer with rights of audience in the Singapore International Commercial Court. Jose is an Associate Member of 3 Verulam Buildings in London. He has advised and acted in numerous shareholder disputes, winding up petitions, and applications arising out of liquidations of companies (for example applications for provisional liquidators, receivers, validation orders, private examinations, unfair preference proceedings). He has also dealt with director disqualification proceedings commenced by the Official Receiver as well as the SFC. He has appeared: - in many creditors petitions including those related to China Huiyuan Juice Group, Hsin Chong Construction Company Ltd, China Solar Energy Holdings, HNA Group Co Ltd, CW Advanced Technologies Ltd and China City Construction Co Ltd. -

Peter Fuhrman, a Tech Investment Banker in China, Analyses Oneplus

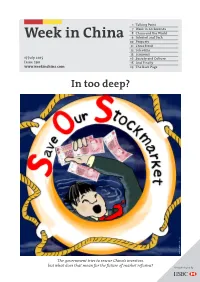

1 Talking Point 7 Week in 60 Seconds 8 China and the World Week in China 9 Internet and Tech 10 Property 11 Cross Strait 12 Telecoms 15 Economy 17 July 2015 16 Society and Culture Issue 290 18 And Finally www.weekinchina.com 19 The Back Page In too deep? m o c . n i e t s p e a t i n e b . w w w The government tries to rescue China’s investors, but what does that mean for the future of market reforms? Brought to you by Week in China Talking Point 17 July 2015 Margin of error Chinese investors have learned just how dangerous margin trading can be Nail-biting period: another volatile week for China’s A-share market here were signs last weekend innovative, benefit the people’,” a ures might mean for China’s longer- Tthat the reverberations in new text message informed the term policy agenda. China’s stock market were starting campus. to reach some of the country’s most The same stipulations might well What have the authorities done to respected universities. be directed to China’s stock market stem the rout? Confidence boosting was the regulators, following a brutal few The theme of our Talking Point a order of the day, according to an weeks for investors. The situation couple of issues ago was investor email sent to students before a on Chinese bourses has been bleak, confusion. The market had turned graduation ceremony at Tsinghua, with shares in Shanghai down for the worse, but government agen- telling them to “follow the instruc- about a third on their mid-June cies were sending out seemingly tion and shout loudly the slogan, peak, and the Shenzhen board contradictory signals. -

WIC Template

1 Talking Point 5 The Week in 60 Seconds 6 Energy and Resources Week in China 7 Internet and Tech 8 Economy 10 China Consumer 11 Media 12 Auto Industry 14 Banking and Finance 4 March 2011 15 Society and Culture Issue 97 19 And Finally www.weekinchina.com 20 The Back Page Gaddafi’s latest shock m o c . n i e t s p e a t i n e b . w w w y b g u in Surprise as Beijing votes for sanctions in unanimous vote by UN Security Council o k y n o a t B s t l t h a e g b k u o r o l a r G M B C d B n S a H Week in China Talking Point 4 March 2011 Beijing’s bold vote Why China broke with foreign policy tradition at the UN last weekend Gaddafi: he must have realised he was in serious trouble when Beijing joined unanimous Security Council vote he last time Tobruk and Beng- That’s because they have be- lutions too. As China-watchers are Thazi hit world headlines was in come the focal point of opposition keenly aware, this marked a major the 1940s when the Libyan cities re- to Libyan dictator Muammar break with the country’s foreign peatedly changed hands in the Gaddafi, in the two-week-old revolt policy traditions. Desert War. First the Italian army against his rule. Gaddafi’s military surrendered them to the British. response to the crisis has seen him Why was it so significant? Then they fell to Rommel’s Panzers, condemned by America and Eu- For the past 30 years or so a funda- before being recaptured from the rope, and the UN Security Council mental principle has underpinned Germans by Montgomery’s Allied voted unanimously last Saturday China’s dealings with other coun- forces. -

Jose-Antonio Maurellet SC BA Jurisprudence (Law), University of Oxford (St

Des Voeux Chambers 38/F Gloucester Tower The Landmark Central, Hong Kong Telephone: 2526-3071 Jose-Antonio Maurellet SC BA Jurisprudence (Law), University of Oxford (St. Edmund Hall) (1999) PCLL, University of Hong Kong (2000) Email Address: [email protected] Year Of Call: 2000 (Hong Kong) 2016 (Hong Kong Inner Bar) Law Society of England & Wales (non practising) Singapore International Commercial Court, Registered Foreign Lawyer Practice Areas: Company and Insolvency Law, Commercial Law, Arbitration Jose-Antonio Maurellet S.C. is a Hong Kong born Eurasian. He is an English, Cantonese and French native speaker. He also can speak some Mandarin. Jose read law at St Edmund Hall, Oxford University. He was called to the Hong Kong Bar in 2000 and to the Inner Bar in 2016. His practice is largely commercial with an emphasis on company and insolvency law. He is a member of the International Insolvency Institute. He has advised and acted in numerous shareholder disputes, winding up petitions, and applications arising out of liquidations of companies (for example applications for provisional liquidators, S.221 examinations, unfair preference proceedings). He has also appeared in schemes involving privatizations (Re eContext and Re Wheelock Properties) as well as creditors schemes (Re Kaisa Group Holdings, Mongolia Mining Corporation and Z-Obee Holdings). He also regularly acts in disputes arising from banking/financial services, in particular alleged mis-selling of financial products. He has previously acted for the Securities and Futures Commission as well as the Listing Division of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong. He has appeared before the Listing Appeals Committee as well as the Takeovers and Mergers Panel. -

Anti-Bribery and Corruption Review June 2017

ANTI-BRIBERY AND CORRUPTION REVIEW JUNE 2017 CONTENTS Global contacts 3 World Map 4 Foreword 6 Europe, the Middle East and Africa 7 Belgium 8 Czech Republic 10 France 12 Germany 14 Italy 18 Luxembourg 19 Poland 20 Romania 21 Russia 24 Slovak Republic 27 Spain 29 The Netherlands 30 Turkey 32 Ukraine 33 United Arab Emirates 35 United Kingdom 37 The Americas 40 Brazil 41 United States of America 43 Asia Pacific 47 Australia 48 Hong Kong 50 Indonesia 52 Japan 54 South Korea 55 People’s Republic of China 57 Singapore 59 Thailand 61 ANTI-BRIBERY AND CORRUPTION REVIEW GLOBAL CONTACTS EUROPE, THE MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA United Arab Emirates Belgium James Abbott +971 4503 2608 Sébastien Ryelandt +32 2533 5988 Matthew Shanahan +971 4503 2723 Dorothée Vermeiren +32 2533 5063 United Kingdom Czech Republic Roger Best +44 20 7006 1640 Jan Dobrý +420 22255 5252 Luke Tolaini +44 20 7006 4666 France Patricia Barratt +44 20 7006 8853 Thomas Baudesson +33 14405 5443 Judith Seddon +44 20 7006 4820 Charles-Henri Boeringer +33 14405 2464 THE AMERICAS Arthur Millerand +33 14405 5446 Brazil Germany Anthony Oldfield +55 113019 6010 Heiner Hugger +49 697199 1283 Patrick Jackson +55 113019 6017 David Pasewaldt +49 697199 1453 United States of America Gerson Raiser +49 697199 1450 David DiBari +1 202912 5098 Jochen Pörtge +49 2114355 5459 Megan Gordon +1 202912 5021 Italy Catherine Ennis +1 202912 5009 Antonio Golino +39 028063 4509 ASIA PACIFIC Luxembourg Australia Albert Moro +352 485050 204 Diana Chang +61 28922 8003 Olivier Poelmans +352 485050 421 Jenni Hill -

Joy and Street Revelry As Kuwait Celebrates Ended in 1990

N IO T IP R C S B U S THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2014 RABI ALTHANI 27, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net 60-year-old Syria army Bitcoin world Real demolish Kuwaiti climbs ambush ‘kills in turmoil Schalke on Liberation 175’ rebels after exchange German soil Tower stairs3 near Damascus8 goes21 dark 20 Joy and street revelry Max 23º Min 12º High Tide as Kuwait celebrates 11:07 & 21:57 Low Tide 04:35 & 16:14 40 PAGES NO: 16089 150 FILS Amir congratulates citizens, residents KUWAIT: (Left) HH the Prime Minister Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah dances with a sword as he toured various areas in the country marking the National and Liberation days. (Center) Alain Robert, the French urban climber dubbed Spiderman, waves the Kuwaiti flag after scaling the Missoni Hotel in Salmiya. (Right) Revelers engage in a water fight on Arabian Gulf Street. — Photos by Yasser Al-Zayyat and KUNA (See Pages 2-6) By Shakir Reshamwala and Agencies ing cars with water under the watchful gaze of security an annual tradition, 60-year-old Kuwaiti athlete Ali Al- Sheikh Sabah recalled the late great leaders - Amir forces, who confiscated water balloons and illegal foam Eidan yesterday climbed the stairs of the 372-m Liberation Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah and Father KUWAIT: Kuwait marked its 53rd National Day and 23rd sprays. Tower in seven minutes and 22 seconds. Amir Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah Al-Salem Al-Sabah - pray- Liberation Day with street celebrations, an air and naval Kuwaiti and Turkish jets performed fly-pasts over the Earlier on Tuesday, HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- ing for their blessed souls and noting their patriotic role show and receptions at the state’s embassies around the Kuwait Towers while the coastguard and Interior Ministry Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah congratulated citizens and resi- in resisting the blatant aggression. -

Top Hong Kong Court Rejects "Thought Crime" Defence in Money Laundering Appeal 1

Top Hong Kong court rejects "thought crime" defence in money laundering appeal 1 Client Briefing August 2016 Top Hong Kong court rejects "thought crime" defence in money laundering appeal In a judgment dealing with the conviction of the former Birmingham City Football Club chairman Carson Yeung, Hong Kong's Court of Final Appeal reaffirmed that, on a charge of dealing with proceeds of crime contrary to section 25(1) Organised and Serious Crimes Ordinance (OSCO), prosecutors have no need to prove that property handled by a defendant is the proceeds of crime, only that the defendant had reasonable grounds to believe it was. The ruling also clarified the mental element of the offence, rejecting the suggestion that an offence can be committed by negligently failing to realise that property was the proceeds of crime. Carson Yeung appealed against his The District Court had heard that conviction in the District Court on various parties, including a Macau Key issues five counts of dealing with property casino, had made more than 400 Prosecutors do not need to believed to be proceeds of an deposits into accounts held by Yeung prove that property handled indictable offence for having and his father. The prosecution did by a defendant is the laundered HKD721 million in Hong not seek to identify the offences from proceeds of crime to establish Kong. Yeung was originally which the monies were said to have an offence under OSCO. sentenced to six years in jail. derived. Instead, the prosecution case was that Yeung must have had All that is required is that the Section 25(1) OSCO says that "a reasonable grounds to believe that defendant had reasonable person commits an offence, if, the monies in question were derived grounds to believe that the knowing or having reasonable from proceeds of crime.