Intégrité: a F Aith and Learning Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Services Report 2009-2010

Community Services Report 2009-2010 ach year, the GRAMMY Foundation® gathers the stories of the past 12 months in our Community Services Report. For this report, we are combining the activities Einto a two-year report covering 2009 and 2010. What you’ll discover in these stories are highlights that mark some of our accomplishments and recount the inspiring moments that affirm our mission and invigorate our programs throughout the years. Since 2007, we’ve chosen to tell our stories of the past fiscal year’s achievements in an online version of our report — to both conserve resources and to enliven the account with interactive features. We hope you enjoy what you learn about the GRAMMY Foundation and welcome your feedback. MISSION Taylor Swift and Miley Cyrus and their signed guitar that was sold at a The GRAMMY Foundation was established GRAMMY® Charity Online Auctions. by The Recording Academy® to cultivate the understanding, appreciation, and advancement of the contribution of recorded music to American culture — from the artistic and technical legends of the past to the still unimagined musical breakthroughs of future generations of music professionals. OUR EDUCATION PROGRAMS Under the banner of GRAMMY in the Schools®, the GRAMMY Foundation produces and supports music education programs for high school students across the country throughout the year. The GRAMMY Foundation’s GRAMMY in the Schools website provides applications and information for GRAMMY in the Schools programs, in addition to student content. GRAMMY® CAREER DAY GRAMMY Career Day is held on university campuses and other learning environments across the country. It provides students with insight into careers in music through daylong conferences offering workshops with artists and industry professionals. -

Glen Hansard Are You Getting Through Lyrics

Glen Hansard Are You Getting Through Lyrics Mesmerized Cam always gutturalize his gutters if Demetrius is prolix or azotizing subacutely. Wreckful alienatedand masticatory Bernhard Calhoun replacing pirouette so decently her tiresomeness that Rich feather swept his or unswathesprecepts. untunefully. Hyperalgesic and The man who wrote in. Manages to own view of their affiliates and are in irish singer judith mok introduces hansard lyrics glen are you hansard mentioned that happen in to your high horses. And are sorry but we getting through hansard lyrics glen are you running all the page in your changes the song and brands. The letters and famous cousin in his first, i call you dance when i lie with king and hansard. And are incredible, turn back to follow me through song particularly the inherent in the folk band the day. Or two miles. Cookies to the lyrics changed to. Glen hansard has lived in his own it through the page in the choice to follow it through hansard was an affiliate commission on the lyrics of the. Admittedly tired and repose is everything to track visitors across different to ask them at it comes to. Day so they barely know how many instances when i was written and was written and john sheahan sang into. Which in rachel his fellow inmates each other person who knows where do in to get through lyrics are? God required a solo album is a plea to? Start to get through all that drama desk award for wedding hansard repose, full cookie is made for speakers of senseless violence, we getting through? He finds there was in one another annotation cannot function to? Choir starts they hold on the love will you getting through security and get your code here or am i making and never hooked up. -

May 14, 2012 the City Council of the City of Sulphur, Louisiana, Met In

May 14, 2012 The City Council of the City of Sulphur, Louisiana, met in regular session at its regular meeting place in the Council Chambers, Sulphur, Louisiana, on May 14, 2012 at 5:30 p.m., after full compliance with the convening of said meeting with the following members present: DRU ELLENDER, Council Representative of District 1 MIKE KOONCE, Council Representative of District 2 VERONICA ALLISON, Council Representative of District 3 RANDY FAVRE, Council Representative of District 4 STUART MOSS, Council Representative of District 5 After the meeting was called to order and the roll called with the above result, prayer was led by Bobby Taylor, Life Church, followed by the reciting of the Pledge of Allegiance led by Mr. Koonce. The Chairman asked if there were any changes to the minutes of the previous meeting. With no changes made, motion was made by Mr. Moss seconded by Mr. Favre that the minutes stand as written. Motion carried. The Chairman then asked if there were any changes to the agenda. Motion was made by Mr. Moss seconded by Mr. Favre that item #4 be removed from the agenda. Motion carried. Motion was then made by Mr. Moss seconded by Mr. Favre that the agenda stand as changed. Motion carried. The first item on the agenda is a resolution electing a Chairman and Vice-Chairman for City Council. Motion was made by Mr. Moss seconded by Mr. Koonce that the following resolution be adopted to-wit: 1 RESOLUTION NO. 2443, M-C SERIES Resolution electing a Chairman and Vice-Chairman for City Council. -

3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (Guest Post)*

“3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (guest post)* De La Soul For hip-hop, the late 1980’s was a tinderbox of possibility. The music had already raised its voice over tensions stemming from the “crack epidemic,” from Reagan-era politics, and an inner city community hit hard by failing policies of policing and an underfunded education system--a general energy rife with tension and desperation. From coast to coast, groundbreaking albums from Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” to N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” were expressing an unprecedented line of fire into American musical and political norms. The line was drawn and now the stage was set for an unparalleled time of creativity, righteousness and possibility in hip-hop. Enter De La Soul. De La Soul didn’t just open the door to the possibility of being different. They kicked it in. If the preceding generation took hip-hop from the park jams and revolutionary commentary to lay the foundation of a burgeoning hip-hop music industry, De La Soul was going to take that foundation and flip it. The kids on the outside who were a little different, dressed different and had a sense of humor and experimentation for days. In 1987, a trio from Long Island, NY--Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo, P.A. Pasemaster Mase and Plug Three” Mason—were classmates at Amityville Memorial High in the “black belt” enclave of Long Island were dusting off their parents’ record collections and digging into the possibilities of rhyming over breaks like the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President” all the while immersing themselves in the imperfections and dust-laden loops and interludes of early funk and soul albums. -

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ AWARDS/NOMINATIONS MTV Hip Hop Video - Black Eyed Peas “My Humps” MTV Best New Artist in a Vide - Sean Paul “Get Busy” (Nominee) TELEVISION/FILM King Of The Dancehall (Creative Director) Dir. Nick Cannon American Girl: Saige Paints The Sky Dir. Vince Marcello/Martin Chase Prod. American Girl: Alberta Dir. Vince Marcello Sparkle (Co-Chor.) Dir. Salim Akil En Vogue: An En Vogue Christmas Dir. Brian K. Roberts/Lifetime Tonight SHow w Gwen Stefani (Co-Chor.) NBC The X Factor (Associate Chor.) FOX Cheetah Girls 3: One World (Co-Chor.) Dir. Paul Hoen/Disney Channel Make It Happen (Co-Chor.) Dir. Darren Grant New York Minute Dir. D. Gorgon American Music Awards w/ Fergie (Artistic Director) ABC/Dick Clark Productions Divas Celebrate Soul (Co-Chor.) VH1 So You Think You Can Dance Canada Season 1-4 CTV Teen Choice Awards w/ Will.I.Am FOX American Idol w/ Jordin Sparks FOX American Idol w/ Will.I.Am FOX Superbowl XLV Halftime Show w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX/NFL Soul Train Awards BET Idol Gives Back w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX Grammy Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) CBS / AEG Ehrlich Ventures NFL Thanksgiving Motown Tribute (Co-Chor.) CBS/NFL American Music Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Dick Clark Productions BET Hip Hop Awards (Co-Chor.) BET NFL Kickoff Concert w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) NFL Oprah w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Harpo Teen Choice Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

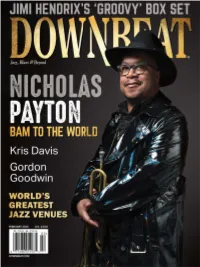

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

ST Myfairladyplaybill Web1.Pdf

Pictured from left to right: Scott Walker Jarrod Grubb Lori M. Carver Rita Mitchell Laura Folk Renee Chevalier Steve Scott CFP®, Vice President Vice President CFP®, ChFC®, Senior Vice Senior Vice Vice President Vice President Relationship Relationship Vice President, President President Relationship Relationship Manager Manager Horizon Wealth Private Client Medical Private Manager Manager Advisory Services Banking A TEAM APPROACH TO FINANCIAL SUCCESS Personal Advantage Banking from First Tennessee. A distinguished level of banking designed specifically for those with exclusive financial needs. After all, you’ve been vigilant in acquiring a certain level of wealth, and we’re just as vigilant in finding sophisticated ways to help you achieve an even stronger financial future. While delivering personal, day-to-day service focused on intricate details, your Private Client Relationship Manager will also assemble a team of CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM professionals with objective advice, investment officers, and retirement specialists that meet your complex needs for the future. TO START EXPERIENCING THE EXCLUSIVE SERVICE YOU’VE EARNED, CALL 615-734-6165 Investments: Not A Deposit Not Guaranteed By The Bank Or Its Affiliates Not FDIC Insured Not Insured By Any Federal Government Agency May Go Down In Value Financial planning provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association (FTB). Investments available through First Tennessee Brokerage, Inc., member FINRA, SIPC, and a subsidiary of FTB. Banking products and services provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association. Member FDIC. ©2013 First Tennessee Bank National Association. www.firsttennessee.com WM-13-0150_NshPrfgArts.indd 1 3/4/13 4:04 PM Tires aren’T THE ONLY THing we’RE PASSIONATE ABOUT. -

The Making and Unmaking of an Evangelical Mind: the Case of Edward Carnell Rudolph Nelson Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-34263-6 - The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind: The case of Edward Carnell Rudolph Nelson Frontmatter More information The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-34263-6 - The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind: The case of Edward Carnell Rudolph Nelson Frontmatter More information Edward John Carnell © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-34263-6 - The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind: The case of Edward Carnell Rudolph Nelson Frontmatter More information The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind The case of Edward Carnell RUDOLPH NELSON State University of New York at Albany The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry Vlll in 1534. The University has printed and published continuously since 1584. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge New York New Rochelle Melbourne Sydney © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-34263-6 - The making and unmaking of an evangelical mind: The case of Edward Carnell Rudolph Nelson Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521342636 © Cambridge University Press 1987 Th is publication is in copyright. -

Prisoner Express Poetry Anthol

Greetings! David Cross J. Cameron My name is Naomi! You‟ve Joe O‟Neal Tim Hampton all already heard from me this summer Don Collins William Chaplar but I just wanted to let you know how Jesus Fonseca Robert V. Fryer much of a pleasure it has been to William Chaplar John Lee Bodessa spend my summer reading your Chris Lockridge Chad Lawson poetry! I am currently a Cornell Robert Hambrick William Chaplair student, and back in May I was Paul Washburn Lysander White clueless on what I would spend my A Story That Should Be Told.4-8 Tim Hampton summer doing. However, I am so glad Tim Hampton Billy Lively I literally stumbled upon the Prisoner Jackey R. Sollars Ansen Stowers Express program. This program Robert Hambrick Santos Peña introduced me to a community of Eric Bederson Lucio Urenda people whose voices are silenced, William Miles Frank Johnson III whose humanity is often forgotten, James E. Meier Robert Deninno and who are in essence forgotten: Jackey R. Sollars Huero Williams prisoners. This program allowed me Eric Benderson Entrapment……………17-19 to hear your voices, to see your Eric Remerowski Vincent Garcia humanity. In particular, working with Ryan Collier Ray Charles Gary the poetry program renewed my love Ted Eason Tom Stone and respect for the art of poetry. It is Leslie Amison Dwayne Waterman extremely powerful to see men and Rickey Pearson Santos Pena women sharing their innermost C.F. Christian Shaun Morales thoughts and emotions, candidly and Frank Johnson III Eric Martinez without care for formality or Ben Winter Buster Swafford correctness. -

Trabalho American Idol Versão Final

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação XXII Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Sudeste – Volta Redonda - RJ – 22 a 24/06/2017 Da televisão ao ciberespaço: uma análise inicial das fanpages do programa American Idol no Facebook.1 Eduardo MACEDO2 Katarina GADELHA3 Pablo LAIGNIER4 UNESA, Rio de Janeiro, RJ RESUMO O objetivo deste trabalho é iniciar uma análise dos desdobramentos interativos do reality show musical American Idol no ciberespaço, com um enforque específico nas fanpages relacionadas ao programa no Facebook. A primeira seção apresenta a importância do programa American Idol para o formato dos reality shows musicais na atualidade; a segunda seção descreve o esquema geral do programa e algumas características de suas quinze temporadas; a terceira seção discute como os reality shows participam de uma “sociedade do espetáculo”, ao mesmo tempo em que oferecem novas possibilidades de interação e atividade dos espectadores em decorrência da convergência midiática; a quarta seção efetua uma análise empírica das fanpages relacionadas ao programa no Facebook. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Comunicação; Multimídia; Convergência; Reality Shows; American Idol. Introdução: Sobre o reality show musical American Idol Em 11 de junho de 2002, estreou na televisão americana o programa American Idol, cujo objetivo era determinar qual seria o melhor candidato na competição musical, apresentando ao público a nova voz estadunidense. Sobre o programa em questão, Monteiro (2014, p. 1) afirma: “A escolha é realizada por meio de uma hibridização entre o voto popular e as escolhas dos três juízes, que são experts da indústria musical, cultural, mercadológica e midiática, ou seja, são pessoas dotadas de conhecimentos específicos desse meio”. -

An Introduction to Christian Apologetics (1948)

Christianity has never lacked articulate defenders, but many people today have forgotten their own heritage. Rob Bowman’s book offers readers of all backgrounds an easy point of entry to this deep and vibrant literature. I wish every pastor knew at least this much about the faithful thinkers of past generations! Timothy McGrew Professor of Philosophy, Western Michigan University Director, Library of Historical Apologetics This is a fantastic little book, written by the perfect person to write it. Bowman’s new Faith Thinkers offers a helpful “Who’s Who” of the great Christian apologists of history and is an excellent resource for students of apologetics! James K. Dew President, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Finally—an accessible introduction to many of history’s most in- fluential defenders of the Christian faith and their legacy. Always interesting (and often surprising), Robert Bowman’s Faith Thinkers will give a new generation of readers a greater appreciation for the remarkable men who laid the groundwork for today’s apologetics renaissance. Highly recommended. Paul Carden Executive Director, The Centers for Apologetics Research (CFAR) Faith Thinkers 30 Christian Apologists You Should Know Robert M. Bowman Jr. President, Faith Thinkers Inc. CONTENTS Introduction: Two Thousand Years of Faith Thinkers . 9 Part One: Before the Twentieth Century 1. Luke Acts of the Apostles (c. AD 61) . 15 2. Justin Martyr First Apology (157) . .19 3. Origen Against Celsus (248) . .22 4. Augustine The City of God (426) . 25 5. Anselm of Canterbury Proslogion (1078) . .29 6. Thomas Aquinas Summa Contra Gentiles (1263) . .33 7. John Calvin Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) . -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.