Botanist Interior 43.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

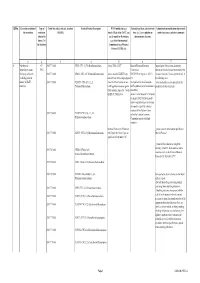

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Huperzine a from Huperzia Species—An Ethnopharmacolgical Review Xiaoqiang Ma A,B, Changheng Tan A, Dayuan Zhu A, David R

Huperzine A from Huperzia species—An ethnopharmacolgical review Xiaoqiang Ma a,b, Changheng Tan a, Dayuan Zhu a, David R. Gang b, Peigen Xiao c,∗ a State Key Laboratory of Drug Research, Institute of Materia Medica, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 201203, PR China b Department of Plant Sciences and BIO5 Institute, The University of Arizona, 303 Forbes Building, Tucson, AZ 85721-0036, USA c Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100094, PR China Abstract Huperzine A (HupA), isolated originally from a traditional Chinese medicine Qiang Ceng Ta, whole plant of Huperzia serrata (Thunb. ex Murray) Trev., a member of the Huperziaceae family, has attracted intense attention since its marked anticholinesterase activity was discovered by Chinese scientists. Several members of the Huperziaceae (Huperzia and Phlegmariurus species) have been used as medicines in China for contusions, strains, swellings, schizophrenia, myasthenia gravis and organophosphate poisoning. HupA has been marketed in China as a new drug for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) treatment and its derivative ZT-1 is being developed as anti-AD new drug candidate both in China and in Europe. A review of the chemistry, bioactivities, toxicology, clinical trials and natural resources of HupA source plants is presented. Keywords: Huperzine A; ZT-1; Alzheimer’s disease; Huperzia serrata; Huperziaceae; Drug discovery; Bioactivities; Clinical trials; Traditional Chinese -

Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas Plant List

Tettegouche State Park Plant List Herbarium Scientific Name Minnesota DNR Common Name Status Abies balsamea balsam fir Acer rubrum red maple Acer spicatum mountain maple Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Adiantum pedatum maidenhair fern Agrostis scabra rough bentgrass Allium tricoccum wild leek Alnus incana rugosa speckled alder Alnus viridis crispa green alder Alopecurus pratensis meadow foxtail Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Amelanchier bartramiana northern juneberry Amelanchier interior inland juneberry Amelanchier laevis smooth juneberry Amelanchier sanguinea sanguinea round-leaved juneberry Amelanchier spicata creeping juneberry Amelanchier wiegandii inland juneberry Arabis pycnocarpa hairy rock cress Arabis pycnocarpa pycnocarpa hairy rock cress Aralia racemosa American spikenard Arctostaphylos uva-ursi bearberry Arnica lonchophylla long-leaved arnica T Artemisia campestris caudata field sagewort Asarum canadense wild ginger Asplenium trichomanes trichomanes maidenhair spleenwort T Astragalus canadensis Canada milk-vetch Athyrium filix-femina angustum lady fern Berberis thunbergii Japanese barberry Betula cordifolia heart-leaved birch Betula papyrifera paper birch Bidens cernua nodding bur marigold Bidens frondosa leafy beggarticks Bidens tripartita tufted beggarticks Boechera grahamii spreading rock cress Botrychium matricariifolium matricary grapefern Botrychium multifidum leathery grapefern Botrychium virginianum rattlesnake fern Brachyelytrum aristosum northern shorthusk Bromus ciliatus fringed brome Calamagrostis canadensis -

The Genus Huperzia (Lycopodiaceae) in the Azores and Madeira

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Biblioteca Digital do IPB Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, 158, 522–533. With 15 figures The genus Huperzia (Lycopodiaceae) in the Azores and Madeira JOSÉ ANTONIO FERNÁNDEZ PRIETO1*, CARLOS AGUIAR2, EDUARDO DIAS3, MARÍA DE LOS ÁNGELES FERNÁNDEZ CASADO1 and JUAN HOMET1 1Área de Botánica, Departamento de Biología de Organismos y Sistemas, Universidad de Oviedo, 33006 Oviedo, Spain 2Área de Biologia, Escola Superior Agrária de Bragança, Campus de Santa Apolónia, Apartado 1172, 5301-855 Bragança, Portugal 3Departamento de Ciências Agrárias, Universidade dos Açores, Campus de Angra, Terra-Chã, 9701-851 Angra do Heroísmo, Açores, Portugal Received 16 February 2005; accepted for publication 15 May 2008 The taxonomy and nomenclature of the genus Huperzia Bernh. in the Azores and Madeira have been reviewed. Plants collected in the Azores and Madeira were characterized morphologically. The independence between two endemic species common to Madeira and the Azores Islands – Huperzia suberecta (Lowe) Tardieu and Huperzia dentata (Herter) Holub – is clearly shown. A clear-cut morphological separation between these taxa and Huperzia selago (L.) Bernh. ex Schrank & Mart. of continental Europe is established. © 2008 The Linnean Society of London, Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, 158, 522–533. ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS: bulbil – Huperzia dentata – Huperzia selago – Huperzia suberecta – nomen- clature – spore – stoma – taxonomy. INTRODUCTION Most authors have accepted this systematic treat- ment of Lycopodiaceae in Europe, including the Lycopodiaceae P.Beauv. ex Mirb. sensu lato is a genera Huperzia, Lycopodium, Diphasiastrum and family with a cosmopolitan distribution, consisting of Lycopodiella (Rothmaler, 1964, 1993; Villar, 1986). -

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited By

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited by: Stephen M. Young and Troy W. Weldy This list is also published at the website: www.nynhp.org For more information, suggestions or comments about this list, please contact: Stephen M. Young, Program Botanist New York Natural Heritage Program 625 Broadway, 5th Floor Albany, NY 12233-4757 518-402-8951 Fax 518-402-8925 E-mail: [email protected] To report sightings of rare species, contact our office or fill out and mail us the Natural Heritage reporting form provided at the end of this publication. The New York Natural Heritage Program is a partnership with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and by The Nature Conservancy. Major support comes from the NYS Biodiversity Research Institute, the Environmental Protection Fund, and Return a Gift to Wildlife. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... Page ii Why is the list published? What does the list contain? How is the information compiled? How does the list change? Why are plants rare? Why protect rare plants? Explanation of categories.................................................................................................................... Page iv Explanation of Heritage ranks and codes............................................................................................ Page iv Global rank State rank Taxon rank Double ranks Explanation of plant -

Lake Champlain Alewife Impacts February 14, 2006 Workshop Summary

Lake Champlain Alewife Impacts February 14, 2006 Workshop Summary Native smelt (top) and alewife from Lake Champlain LCSG-05-06 Planning Committee: J. Ellen Marsden, Univ. of Vermont, Burlington, VT Eric Palmer, VTFW, Waterbury, VT Bill Schoch, NYSDEC, Ray Brook, NY Dave Tilton, USFWS, Essex Junction, VT Lisa Windhausen, LCBP, Grand Isle, VT Mark Malchoff, LCSG/SUNY Plattsburgh LCRI, Plattsburgh, NY Lake Champlain Sea Grant 101 Hudson Hall, Plattsburgh State University of NY 101 Broad Street Plattsburgh, NY 12901-2681 http://research.plattsburgh.edu/ LakeChamplainSeaGrantAquatics/ans.htm and Lake Champlain Basin Program 54 West Shore Road - Grand Isle, VT 05458 http://www.lcbp.org/ 2 To Alewife Workshop Participants and Interested Parties: August 23, 2006 Alewives are native to the Atlantic coast and typically spawn in freshwater rivers and lakes. They are commonly used as bait and have become established in many lakes across the United States following intentional introductions and accidental bait-bucket releases. Once established in a new waterbody, alewives can cause tremendous changes to a lake ecosystem. Alewives first ap- peared in Lake Champlain’s Missisquoi Bay in 2003; they appeared in the Northeast Arm and the Main Lake segments in 2004 and 2005. Alewives are well established in Lake St. Catherine, which drains to Lake Champlain 80+ miles south of the 2004 discovery point. Based on experiences in other states, it is believed that an alewife infestation in Lake Champlain could have substantial eco- nomic and ecological impacts. Because the specific impacts of a widespread alewife infestation on Lake Champlain are uncertain, Lake Champlain Sea Grant and the Lake Champlain Basin Program organized a workshop on February 14, 2006 to learn from resource managers and scientists with experience in the Great Lakes and Finger Lakes of New York. -

81 Vascular Plant Diversity

f 80 CHAPTER 4 EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS UNIT II EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF PLANTS 81 LYCOPODIOPHYTA Gleicheniales Polypodiales LYCOPODIOPSIDA Dipteridaceae (2/Il) Aspleniaceae (1—10/700+) Lycopodiaceae (5/300) Gleicheniaceae (6/125) Blechnaceae (9/200) ISOETOPSIDA Matoniaceae (2/4) Davalliaceae (4—5/65) Isoetaceae (1/200) Schizaeales Dennstaedtiaceae (11/170) Selaginellaceae (1/700) Anemiaceae (1/100+) Dryopteridaceae (40—45/1700) EUPHYLLOPHYTA Lygodiaceae (1/25) Lindsaeaceae (8/200) MONILOPHYTA Schizaeaceae (2/30) Lomariopsidaceae (4/70) EQifiSETOPSIDA Salviniales Oleandraceae (1/40) Equisetaceae (1/15) Marsileaceae (3/75) Onocleaceae (4/5) PSILOTOPSIDA Salviniaceae (2/16) Polypodiaceae (56/1200) Ophioglossaceae (4/55—80) Cyatheales Pteridaceae (50/950) Psilotaceae (2/17) Cibotiaceae (1/11) Saccolomataceae (1/12) MARATTIOPSIDA Culcitaceae (1/2) Tectariaceae (3—15/230) Marattiaceae (6/80) Cyatheaceae (4/600+) Thelypteridaceae (5—30/950) POLYPODIOPSIDA Dicksoniaceae (3/30) Woodsiaceae (15/700) Osmundales Loxomataceae (2/2) central vascular cylinder Osmundaceae (3/20) Metaxyaceae (1/2) SPERMATOPHYTA (See Chapter 5) Hymenophyllales Plagiogyriaceae (1/15) FIGURE 4.9 Anatomy of the root, an apomorphy of the vascular plants. A. Root whole mount. B. Root longitudinal-section. C. Whole Hymenophyllaceae (9/600) Thyrsopteridaceae (1/1) root cross-section. D. Close-up of central vascular cylinder, showing tissues. TABLE 4.1 Taxonomic groups of Tracheophyta, vascular plants (minus those of Spermatophyta, seed plants). Classes, orders, and family names after Smith et al. (2006). Higher groups (traditionally treated as phyla) after Cantino et al. (2007). Families in bold are described in found today in the Selaginellaceae of the lycophytes and all the pericycle or endodermis. Lateral roots penetrate the tis detail. -

The Huperzia Selago Shoot Tip Transcriptome Sheds New Light on the Evolution of Leaves

GBE The Huperzia selago Shoot Tip Transcriptome Sheds New Light on the Evolution of Leaves Anastasiia I. Evkaikina1,†, Lidija Berke2,†,MarinaA.Romanova3, Estelle Proux-We´ra4,5, Alexandra N. Ivanova6, Catarina Rydin7, Katharina Pawlowski7,*, and Olga V. Voitsekhovskaja1 1Laboratory of Molecular and Ecological Physiology, Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia 2Department of Plant Sciences, Wageningen University, The Netherlands 3Department of Botany, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia 4Department of Plant Protection Biology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden 5Science for Life Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Stockholm University, Solna, Sweden 6Laboratory of Anatomy and Morphology, Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia 7Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden †These authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: August 28, 2017 Data deposition: Raw sequence reads used for the de novo transcriptome assembly were deposited at NCBI GenBank (accession PRJNA281995). Huperzia selago phylogenetic markers: KX761189, KX761188, KX761187 KNOX cDNAs: KX761181 - KX761185 YABBY cDNA: KX761186 YABBY genomic: MF175244. Abstract Lycopodiophyta—consisting of three orders, Lycopodiales, Isoetales and Selaginellales, with different types of shoot apical meristems (SAMs)—form the earliest branch among the extant vascular plants. They represent a sister group to all other vascular plants, from which they differ in that their leaves are microphylls—that is, leaves with a single, unbranched vein, emerging from the protostele without a leaf gap—not megaphylls. All leaves represent determinate organs originating on the flanks of indeterminate SAMs. Thus, leaf formation requires the suppression of indeterminacy, that is, of KNOX transcription factors. -

Characteristics of Atypical Huperzia Selago Subsp. Arctica Habitats to the South of Distribution Area

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae Journal homepage: pbsociety.org.pl/journals/index.php/asbp ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Received: 2011.11.18 Accepted: 2012.05.14 Published electronically: 2012.05.30 Acta Soc Bot Pol 81(2):87-92 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.2012.016 Characteristics of atypical Huperzia selago subsp. arctica habitats to the south of distribution area Ilona Jukonienė*, Rasa Dobravolskaitė, Jūratė Sendžikaitė Nature Research Centre, Institute of Botany, Žaliųjų Ežerų 49, 08406 Vilnius, Lithuania Abstract Two localities for Huperzia selago subsp. arctica are recorded from Lithuania, to the south of its known distribution area. The habitats of this subspecies are cutover peatlands whose natural vegetation was disturbed 6-8 years ago during peat exploitation. One of the dominant species of latest vegetation cover is the invasive bryophyte Campylopus introflexus. Characteristics of the habitats of H. selago subsp. arctica and the frequency of this taxon in populations were analysed. Keywords: Campylopus introflexus, cutover peatlands, distribution area, Huperzia selago subsp. arctica, Lithuania, population Introduction Flora Nordica [2] and the New Flora of the British Isles [11]. This last classification, namely, that H. selago consists of two subspe- The species Huperzia selago Bernh. s.l. comprises an assem- cies, is the one adopted in the present paper. blage of morphologically diverse plants [1]. Those from high- and The subspecies arctica has a circumpolar distribution with a mid-alpine habitats are low-growing and compact, yellow-green distribution range that includes both arctic and boreal zones. This and have appressed leaves. Moreover, they produce abundant subspecies has been recorded from Finland, Iceland, Norway, bulbils. -

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

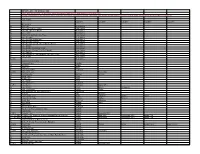

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F. -

D: Rare Plants Species and Wildlife Habitats

Appendix D – Rare Plant Species and Wildlife Habitats Rare Plant Species and Wildlife Habitats The habitat profiles created for the Wildlife Action Plan have been developed for the purpose of describing the full range of habitats that support New Hampshire’s wildlife species. However, these habitats can also serve as useful units for identifying rare plant habitats. This appendix provides lists of rare plant species known to be associated with each WAP habitat type. In accordance with the Native Plant Protection Act (NH RSA 217-A), the New Hampshire Natural Heritage Bureau (NHB) maintains a list of the state’s rarest and most imperiled plant species. This list has been developed in cooperation with researchers, conservation organizations, and knowledgeable amateur botanists. Plant locations have been obtained from sources including herbarium specimens, personal contacts, the scientific literature, and through extensive field research. The list is updated regularly to reflect changes in information. For each habitat, a list of associated rare plant species is presented. These rare plant – habitat associations are based on known occurrences of each species in New Hampshire. It is possible that an individual species will have different habitat associations elsewhere in its range. For more information on dominant and characteristic plant species for each habitat, refer to the individual habitat profiles. For each species, the following information is provided: Scientific name: The primary reference used is: Haines, Arthur. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae: A Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. Yale University Press. New Haven and London. Common name: Many plant species have more than one common name, and some common names are applied to multiple species. -

A Revised Lake Trout Rehabilitation Plan for Ontario Waters of Lake Huron

A Revised Lake Trout Rehabilitation Plan for Ontario Waters of Lake Huron Upper Great Lakes Management Unit - Lake Huron 1 Upper Great Lakes Management Unit, Lake Huron Office MR-LHA- A Revised Lake Trout Rehabilitation Plan for Ontario Waters of Lake Huron May 4, 2012 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Upper Great Lakes Management Unit, Lake Huron Office 2 ©2012, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Upper Great Lakes Management Unit, Lake Huron Office Ministry of Natural Resources 1450 7th Avenue East Owen Sound, Ontario N4K 2Z1 (519) 371-0420 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES.............................................................................................. III LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................ III INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 WHY REHABILITATE LAKE TROUT? ............................................................................. 2 OVERVIEW OF PAST REHABILITATION EFFORTS .................................................... 3 SYNOPSIS OF PROGRESS TOWARDS LAKE TROUT REHABILITATION IN ONTARIO WATERS ............................................................................................................... 5 REVIEW OF THE 1996 PLAN ............................................................................................... 7 A REVISED GOAL AND OBJECTIVES FOR LAKE TROUT REHABILITION....................................................................................................