Karen Malone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Elise and the Gold Gloop by S.B. Davies S.B

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Elise and the Gold Gloop by S.B. Davies S.B. Davies. At the age of six, my daughter was a good reader for her age, but refused to start reading “proper books” with chapters and no pictures. She was bored with “Horrid Henry” and fairies saving a rainbow yet once more and insisted that she was old enough to read proper books, but every one she tried was “too difficult”. It wasn’t she couldn’t read them, it was the concepts and storylines; they were all designed for nine and ten year olds. There was another problem too. She wanted to read about girls, yet all the books about girls we could find were twee and dull. My daughter is happy to read about a princess, along as she is a Ninja Princess; happy to save rainbows, as long as it involves a good sword fight or perhaps a well-planned heist. After a few months of this, my lovely daughter stopped reading. We tried most of the “first chapter books” that people recommend; all met with disinterest. So I asked her exactly what she wanted in a “proper book”. After much though, she wrote down: “Dragons, princess, zombies, vampires, ghosts, but not spiders and it should be funny and scary and have fighting in it.” We couldn’t find such a book with concepts and vocabulary suitable for a six year old – so I wrote one. I had written novels before, but not a children’s book, so I had help from my daughter to find the right level. -

Wanderers Count on Family Unity to Push Them Over Final Line Womens' All Stars Squads Named for NEAFL Round Two Bout

32 SPORT FRIDAY MARCH 14 2014 Wanderers count on family unity to push them over final line By GREY MORRIS the grand final, is ready for a ney (Shane Thorne) who “But even though it’s a great won’t beat Saints. The formula over your shoulder, even when NTFL repeat performance. hasn’t been at his best since opportunity, there is a very for beating them is pretty you’re in front,’’ he said. “Dis- And he will have Daniel Daniel was suspended.’’ tough side standing in our way. tough as well. Four quarters, tricts were four goals up with WANDERERS’ joint skipper back in the side after the for- Motlop smiled when re- “We’ve got to lift in goalk- running both ways and grab- five minutes left in their match Aaron Motlop concedes his mer AFL star completed his minded of the Saturday night icking. I’m not sure what we bing any opportunity we get against Saints and they still side has been undermanned suspension last week. three years ago when he won kicked against Tahs last week, with both hands.’’ came back and beat them. since his cousin Daniel was “There’s been a few players the Chaney Medal as the best I think it was 11.11, but it wasn’t Motlop said St Marys’ mid- “We’ve got Liam Patrick, suspended for nine matches in who have not played their best player on the ground and as many goals as we would field was so good, their back- Chris Dunne and Thomas early January. -

36 the Ian Potter Foundation Annual Report

36 The Ian Potter Foundation Annual Report The Potter name in the Environment & Conservation area is perhaps most synonymous with the funding of an ‘exercise in farm planning’, which would become known as the Potter Farmland Plan. Twenty years on, the Potter Farmland Plan continues to infl uence the agenda for funding by the Foundation. Sustainable development of land and land management practices remain at the forefront of the Foundation’s funding guidelines and practices. The Foundation believes that community, government and business partnerships are the key to solving the great environmental challenges of our time. The Ian Potter Foundation continues to support and promote the funding of research and on-the-ground works that promote the preservation of species and increase public awareness of the environmental challenges facing Australian communities. Funding Objectives • To develop partnerships with communities, government and the private sector to help prevent irreversible damage to the environment and to encourage the maintenance of biodiversity • To support programs and policies that are committed to the economic and ecologically sustainable development of land, and the preservation of species • To foster a broad public awareness of the environmental challenges facing urban and rural Australia • To assist communities that are threatened with serious economic hardship due to the degradation of land and water resources, and to develop policies to manage the social, economic and cultural changes needed for survival • To assist projects -

2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017

Australian Football League Annual Report 2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017 4 2017 Highlights 16 Chairman’s Report 26 CEO’s Report 36 Strong Clubs 44 Spectacular Game 68 Revenue/Investment 80 Financial Report 96 Community Football 124 Growth/Fans 138 People 144 Awards, Results & Farewells Cover: The 37-year wait is over for Richmond as coach Damien Hardwick and captain Trent Cotchin raise the premiership cup; co-captains Chelsea Randall and Erin Phillips with coach Bec Goddard after the Adelaide Crows’ historic NAB AFLW Grand Final win. Back Cover: Richmond star Jack Riewoldt joining US Jubilant Richmond band The Killers on fans erupt around the stage at the Grand MCG at the final siren Final Premiership as the Tigers clinch Party was music their first premiership to the ears of since 1980. Tiger fans. 100,021 The attendance at the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final 3,562,254 The average national audience on the Seven Network for the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, which was the most watched program of any kind on Australian television in 2017. This was made up by an audience of 2,714,870 in the five mainland capital cities and an audience in regional Australia of 847,384. 16,904,867 The gross cumulative audience on the Seven Network and Fox Footy Channel for the 2017 Toyota AFL Finals Series. Richmond players celebrate after defeating the Adelaide Crows in the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, 4 breaking a 37-year premiership drought. 6,732,601 The total attendance for the 2017 Toyota AFL Premiership Season which was a record, beating the previous mark of 6,525,071 set in 2011. -

Abbey Holmes Angela Foley

RESIDENTTERRIFIC TERRITORIANS ANGELA FOLEY ABBEY HOLMES WOMEN’S AFL WOMEN’S AFL ALWAYS FIRST KICKING GOALS Success seems to follow Angela Foley wherever she goes When future historians look back at the inaugural season of the and her premiership medals are building. She’ll be forever AFL Women’s League, Abbey Holmes’ name will be there in the remembered as a winner in the inaugural AFL Women’s winning Adelaide Crows team and making the Territory proud. League after the Adelaide Crows beat the undefeated It’s difficult to believe that the 170cm model-like blonde is one Brisbane Lions in the AFLW Finals in March. of the new breed of AFL women’s footballers, and also the first It was easy to see the wet season humidity didn’t bother her woman in Australia and the Northern Territory to kick over as she sat on the balcony watching the afternoon storm roll 100 goals — actually 105 from 14 games for Tahs in her first in. More obvious were the physical bruises. ‘Everyone of them NTFL season during 2014. ‘I even received congratulatory text is absolutely worth it,’ she laughs. ‘To be the outright winners messages from Warwick Capper and my childhood sporting hero of the AFLW is more than a dream come true, it’s definitely Andrew McLeod,’ recalls 26 year old Abbey. one for the history books.’ As well as being a businesswoman and television reporter, her Ange is the Adelaide Crows Co-Vice Captain and was the first sporting background is in netball. ‘I’ve represented Australia NT player to be selected for the new women’s league team at junior level, as well as South Australia and NT at underage last year. -

2019 Annual Report 2019 Premiers

2019 ANNUAL REPORT2019 ANNUAL 2019 ANNUAL 2019 REPORT PREMIERS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE AUSTRALIAN 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 3 19/2/20 13:54 CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 123RD ANNUAL REPORT 2019 4 2019 Highlights 14 Chairman’s Report 24 CEO’s Report 34 Football Operations 44 AFL Women’s 54 Broadcasting 60 Game Development, Legal & Integrity 84 Commercial Operations 100 Growth, Digital & Audience 108 Strategy 114 People & Culture 118 Inclusion & Social Policy 124 Corporate Affairs 130 Infrastructure 134 Awards, Results & Farewells 154 Financial Report The MCG was filled Cover: The jubilant Back Cover: Tayla Harris to capacity when the Richmond and displays her perfect kicking Giants, playing in their Adelaide Crows teams style, an image that will go first Grand Final, did celebrate their 2019 down as a pivotal moment battle with the Tigers. premiership triumphs. in the women’s game. 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 6 19/2/20 13:54 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 9 19/2/20 13:54 100,014 The attendance at the 2019 Toyota AFL Grand Final 2,938,670 Television audience for the Toyota AFL Grand Final. 6,951,304 Record home and away attendance. Five-goal hero Jack Riewoldt whips adoring Tiger fans into a frenzy after Richmond’s emphatic 4 Grand Final win over the GWS Giants. 4-13_2019 Annual Report_Highlights_FA.indd 4 25/2/20 14:24 4-13_2019 Annual Report_Highlights_FA.indd 5 25/2/20 14:24 1,057,572 Record total club membership of 1,057,572, compared with 1,008,494 in 2018 35,108 Average home and away match attendance of 35,108, compared with 34,822 in 2018. -

3 September 2013 (Extract from Book 11)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 3 September 2013 (Extract from book 11) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry (from 22 April 2013) Premier, Minister for Regional Cities and Minister for Racing .......... The Hon. D. V. Napthine, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for State Development, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development ................................ The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. M. A. O’Brien, MP Minister for Innovation, Services and Small Business, Minister for Tourism and Major Events, and Minister for Employment and Trade .. The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations ..................................................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing .......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs .... The Hon. H. F. Delahunty, MP Minister for Education ............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Planning ............................................. The Hon. M. J. Guy, MLC Minister for Higher Education and Skills, and Minister responsible for the Teaching Profession ....................................... -

Contents Visitors

DEBATES – Thursday 23 March 2017 CONTENTS VISITORS ................................................................................................................................................. 1347 Moulden Primary School ....................................................................................................................... 1347 Speaker’s statement ................................................................................................................................. 1347 Terror Attacks in London ....................................................................................................................... 1347 LEAVE OF ABSENCE .............................................................................................................................. 1347 Deputy Chief Minister ............................................................................................................................ 1347 MINISTERIAL ARRANGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 1348 Question Time ....................................................................................................................................... 1348 MINISTERIAL STATEMENT ..................................................................................................................... 1348 Supporting Territory Women ................................................................................................................. 1348 VISITORS ................................................................................................................................................ -

Foundation Members of the Crows Women's Team

2017 Foundation Members of the Crows Women’s Team (SINCE 2017) Claire Adams Anne Cahill Lambert Amanda Eastham Emma Alexander Sharon Cameron Marc Edwards Ruby Allan Christopher Camp Joyleen Egmanis Sarah Allan Melissa Campbell Rebekah Eley Christine Armitstead Catherine Carey Michael El’helou Justin Ayres Andrea Carli Catherine Evans Jake Azzalini Ben Carter Julie Evans Sean Bache Carol Carter Marie Evans Bev Baldock Edwina Carter Rebecca Evans Amelia Bartter Jenni Carter Sam Faehse Bronwyn Bartter Natalie Castree Matthew Fairley Eleanor Bartter Rahul Chakrabarti Mark Fairway Zara Baxter Josh Champion Caitriona Fay Bec Bebbington Claire Christie Karli Ferguson Michelle Beinke Katherine Clarke Alison Ferrall Bethany Bell Ashlyn Clift Alison Flanegan-Elder Andrew R Bennett Libby Clift Angela Foley Shanti Berggren Kevin Clifton Loraine Foley Lohmann Berny Kelly Clover Sarah Fordham-Young Georgia Bevan Pauline Clover Antony Francis Nadia Bevan Claire Clutterham Kaylene French Scott Bigg Val Coe Phil Gabell Jon Billows Stephen Coles Casey Galbraith Rachel Bills Jack Connell Katrina Gill Renata Bird Catherine Cooper Heather Glynn-Roe Rebecca Birrell Brooke Copeland Helen Goddard Zoe Blundell Craig Coulson Joyce Goddard Kirsty Boath Carolyn Cox Phillipa Goode David Borlace Dayna Cox Eve Goodings Mackenzie Bourke Dean Cox Peter Goodrich Paul Bovington Courtney Cramey Philip Gregory Rebecca Bowering Lisa Croke Liam Griffiths Pat Bradley Stephanie Croke Allan Hall Ros Braham Kerin Cross Tess Hall Chanelle Braithwaite Luke Cunningham Simon Hargrave -

We Are Well Into the 2016/17 Season Now. Mo

Welcome Warriors - new and old - it is great to have you with us! We are well into the 2016/17 season now. Most teams have 6 or 7 games under their belt - so let’s take a look and see how they are all traveling……………………. enjoy! U12 ATKINSON – Well what a ‘ding-dong’ battle Tahs U12’s had against Nightcliff! From the opening bounce one could sense this was going to be a ripper game and it did not disappoint. Nightcliff edged ahead by a goal at quarter time.. only to be overtaken in the 2nd quarter by a Tahs outfit that found their mojo.. Tahs going into the main break 3 points up. 3rd quarter - much the same - a tight tussle . 4th quarter the game was broken open in the opening minutes by a brilliant, crumbing goal by Jack Rieniets who mopped up a spilled contested mark between Tahs ‘big fella’ Ty Aitken and Nightcliff’s full back, ran 15m and kicked truly…. But wait there was more brilliance from one of the Tiwi superstars Sylvanus Tipiloura, right foot snap over-the- shoulder GOAL… the game had been put out of Nightcliff’s reach. GO THE TAHS !!! U14 GUNDERSON – U14 LEW FATT – Coming off two hard fought wins against Palmerston The boys have just recently come together as the and St Marys, this week we came up against an in- Division two team and Friday night was there form Nightcliff outfit. Our boys started slowly and second game as a team. They played a great game were down by 53 points at half time. -

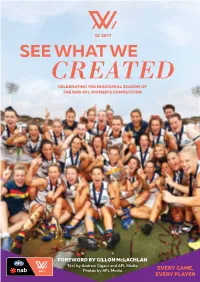

See What We Created Celebrating the Inaugural Season of the Nab Afl Women’S Competition

SEE WHAT WE CREATED CELEBRATING THE INAUGURAL SEASON OF THE NAB AFL WOMEN’S COMPETITION FOREWORD BY GILLON MCLACHLAN Text by Andrew Gigacz and AFL Media 1 Photos by AFL Media EVERY GAME, EVERY PLAYER SEE WHAT WE CREATED CONTENTS A revolution achieved BY GILLON MCLACHLAN A season that changed the game forever BY MICHELLE CLYNE Unforgettable: that’s what it was BY ANDREW GIGACZ ROUND 1: They came in droves ROUND 2: The early favourites stumble ROUND 3: Drawn to success ROUND 4: The Crows and Lions break away ROUND 5: We’ve got the close ones ROUND 6: Be bold for change ROUND 7: The season draws to a close GRAND FINAL: A truly Grand Final 2017 AFLW BEST ON GROUND: Erin Phillips THE AWARDS THE 214 THAT LED THE WAY, AND THEIR CLUBS Adelaide Crows Brisbane Lions Carlton Blues THE WAIT IS OVER: Carlton's Collingwood Magpies captain Lauren Arnell has her team ready to run on to the Fremantle Dockers Blues' home ground, Ikon Park, for the first AFLW match, GWS Giants against Collingwood. Melbourne Demons Western Bulldogs 2 3 SEE WHAT WE CREATED SEE WHAT WE CREATED NO HOLDING BACK: Collingwood marquee player Moana Hope fends off Crows tackler Georgia Bevan. 4 5 SEE WHAT WE CREATED SEE WHAT WE CREATED ROUND 1 THEY CAME IN DROVES The question of whether the public enthusiasm for an elite national women’s competition would match that of the players was emphatically answered in a memorable opening round. HERE had been plenty of hype leading into the first round of AFL Women’s, but what unfolded in Melbourne and Adelaide on the first Tweekend of February was beyond the wildest dreams of even the most optimistic.