Food and Cooking of the Working Class About 1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

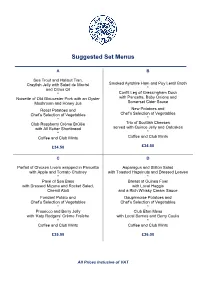

Scottish Menus

Suggested Set Menus A B Sea Trout and Halibut Tian, Crayfish Jelly with Salad de Maché Smoked Ayrshire Ham and Puy Lentil Broth and Citrus Oil * * Confit Leg of Gressingham Duck Noisette of Old Gloucester Pork with an Oyster with Pancetta, Baby Onions and Somerset Cider Sauce Mushroom and Honey Jus Roast Potatoes and New Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Club Raspberry Crème Brûlée Trio of Scottish Cheeses with All Butter Shortbread served with Quince Jelly and Oatcakes * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £34.50 £34.50 C D Parfait of Chicken Livers wrapped in Pancetta Asparagus and Stilton Salad with Apple and Tomato Chutney with Toasted Hazelnuts and Dressed Leaves * * Pavé of Sea Bass Breast of Guinea Fowl with Dressed Mizuna and Rocket Salad, with Local Haggis Chervil Aïoli and a Rich Whisky Cream Sauce Fondant Potato and Dauphinoise Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Prosecco and Berry Jelly Club Eton Mess with ‘Katy Rodgers’ Crème Fraîche with Local Berries and Berry Coulis * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £35.00 £36.00 All Prices Inclusive of VAT Suggested Set Menus E F Confit of Duck, Guinea Fowl and Apricot Rosettes of Loch Fyne Salmon, Terrine, Pea Shoot and Frissée Salad Lilliput Capers, Lemon and Olive Dressing * * Escalope of Seared Veal, Portobello Mushroom Tournedos of Border Beef Fillet, and Sherry Cream with Garden Herbs Fricasée of Woodland Mushrooms and Arran Mustard Château Potatoes and Chef’s Selection -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

Hot & Cold Fork Buffets

HOT & COLD FORK BUFFETS Option 1- Cold fork buffet- £14.00 + vat - 2 cold platters, 3 salads and 1 sweet Option 2 - £15.50 + VAT - 1 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 1 Sweet Option 3 - £22.00 + VAT - 2 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 2 Salads, 2 Sweets Add a cold platter and 2 salads to your menu for £5.25 + VAT per person. Makes a perfect starter. COLD PLATTERS Cold meat cuts (Ayrshire ham, Cajun spiced chicken fillet and pastrami Platter of smoked Scottish seafood) Scottish cheese platter with chutney and Arran oaties (Supplement £4 pp & vat) Duo of Scottish salmon platter (poached and teriyaki glazed) Moroccan spice roasted Mediterranean vegetables platter MAINS Collops of chicken with Stornoway black pudding, Arran mustard mash potatoes and seasonal greens Baked seafood pie topped with parmesan mash, served with steamed buttered greens Tuscan style lamb casserole with tomato, borlotti beans and rosemary with pan fried polenta Roast courgette and aubergine lasagne with roasted Cajun spiced sweet potato wedges Jamaican jerk spice rubbed pork loin with spiced cous cous and honey and lime roasted carrots. Chicken, peppers and chorizo casserole in smoked paprika cream with roasted Mediterranean vegetables and braised rice Balsamic glazed salmon fillets with steamed greens and baby potatoes with rosemary, olive oil and sea salt Haggis, neeps and tatties, served with a whisky sauce Braised mini beef olives with sausage stuffing in sage and onions gravy with creamed potatoes All prices exclusive of VAT. Menus may be subject to change -

The Gladstone Review

SAMPLE ARTICLES FROM THE GLADSTONE REVIEW As it is likely that several readers of this e-journal have discovered the existence of the New Gladstone Review for the first time, I thought it would be helpful to give more idea of the style adopted by providing some examples of articles that were published during 2017. I begin with the introduction on page 1 of the January 2017 issue, and thereafter add seven articles published in subsequent issues. THE GLADSTONE REVIEW January 2017 a monthly e-journal Informal commentary, opinions, reviews, news, illustrations and poetry for bookish people of philanthropic inclination INTRODUCTION This is the first issue of the successor to the Gladstone Books Newsletter, the publication which was launched in November 2015 in association with the Gladstone Books shop in Southwell. The shop was named after William Gladstone, who became an MP for near-by Newark when only 23 years old in 1832, and was subsequently Liberal Prime Minister on four occasions until his death in 1898. It was Gladstone's bibliophilia, rather than his political achievements, that led to adoption of this name when I first started selling second-hand books in Newark in 2002. For he was an avid reader of the 30,000 books he assembled in his personal library, which became the nucleus of the collection in St Deiniol’s library in north Wales, and which is his most tangible legacy. I retained the name when moving the business to Lincoln in 2006, and since May 2015, to the shop in Southwell. * Ben Mepham * Of course, Gladstone Books is now back in Lincoln! Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017): an obituary The name of Zygmunt Bauman, who died last month, while largely unknown to the general public, reputedly induced a state of awe among his fellow sociologists. -

Does the Food System Constrict Healthy Choices for Typical British Families?

FORCE-FED Does the food system constrict healthy choices for typical British families? Contents Acronyms .......................................................................... 03 Chapter 2: Environmental costs .......................................................... 39 Acknowledgements .......................................................... 03 The food our families eat, and throw away ...................... 22 A yoghurt ........................................................................... 40 Funding ............................................................................. 03 Where typical family food comes from Cost of ingredients ............................................................ 40 Executive Summary ........................................................... 04 and how much it costs ...................................................... 23 Efficiencies of scale ............................................................ 40 Introduction ...................................................................... 07 What typical families actually buy and eat ....................... 24 Advertising ......................................................................... 40 What is a ‘typical’ family? ................................................. 09 Retail purchases ................................................................ 24 Potatoes ............................................................................. 40 Report overview ................................................................ 09 Eating -

Hutman Productions Publications Each Sale Helps Us to Maintain Our Informational Web Pages

Hutman Productions Publications Mail Order Catalog, 4/17/2020 P R E S E N T S: The Very Best Guides to Traditional Culture, Folklore, And History Not Just a "good read" but Important Pathways to a better life through ancient cultural practices. Each sale helps us to maintain our informational web pages. We need your help! For Prices go Here: http://www.cbladey.com/hutmanbooks/pdfprices.p df Our Address: Hutman Productions P.O. 268 Linthicum, Md. 21090, U.S.A. Email- [email protected] 2 Introduction Publications "Brilliant reference books for all the most challenging questions of the day." -Chip Donahue Hutman Productions is dedicated to the liberation of important resources from decaying books locked away in reference libraries. In order for people to create folk experiences they require information. For singing- people need hymnals. Hutman Productions gathers information and places it on web pages and into publications where it can once again be used to inform, and create folk experiences. Our goal is to promote the active use in folk experiences of the information we publish. We have helped to inform countless weddings, wakes, and celebrations. We have put ancient crafts back into the hands of children. We have given songs to the song less. We have provided delight and wonder to thousands via folklore, folk music and folk tale. We have made this information freely accessible. We could not provide these services were it not for our growing library of 3 publications. Take a moment to look them over. We hope that you too can use them as primary resources to inform the folk experiences of your life. -

Records of Dorothy Hartley (1893-1985)

RECORDS OF DOROTHY HARTLEY (1893-1985) Accession no : D69/81, D70/3, D70/4, D77/30, D78/31, DX365 Catalogue mark : D HART Introduction Dorothy Rosaman Hartley was born at Skipton, Yorkshire in 1893. Her father was headmaster of Skipton (Yorkshire) Boys’ School but failing eyesight caused him to give up this job and the family moved to Rempston, Nottinghamshire when Dorothy was 12. She went to Art School and during World War I worked in a munitions factory where she received a commendation. In 1919 she entered Regent Street Polytechnic to study art. In 1925 The Land and Peoples of England which she had co-written with Madge Elliot was published. During the 1930’s Dorothy Hartley published weekly articles in the Daily Sketch dealing with all kinds of rural matters and she continued producing books - The Countryman’s England (1935), Made in England (1939), Food in England (1954), Water in England (1964), The Land of England (1979). Between writing she painted, taught, lectured and was an acknowledged draughtsman and photographer. In 1985 she died at Fron House, Llangollen in North Wales where she had lived for over fifty years. Records deposited as a gift and subsequently as a bequest. List compiled February-March 1998 Record types A1 Biographical and Personal C1-16 Research Material D1-8 Reference Material E1-6 Published Work F1-148 Draft Copies of Work G1 Painting H1- I1 Filmstrip A BIOGRAPHICAL AND PERSONAL A1 FILE containing biographical information about Dorothy 1985-1997 Hartley including an entry for the Dictionary of National Biography, -

Food Quiz - Answers a Food Quiz About the Specialities of the British Islands

Food Quiz - Answers A food quiz about the specialities of the British Islands 1. What fish is traditionally used to make an Arbroath Smokie? Haddock 2. Which Leicester town is famous for its Pork Pies? Melton Mowbray 3. What spice is used to flavour the Northern speciality Parkin? Ginger 4. Which London departmental store claims to have invented Scotch Eggs? Fortnum & Mason 5. What is a fillet of beef coated with before being wrapped in parma ham and pastry to become a Beef Wellington? Pate & Mushrooms 6. What sauce is traditionally served with roast lamb? Mint Sauce 7. The innards of which animal are usually used to make Haggis? Sheep 8. What food is celebrated with an annual festival on the Isle of Wight? Garlic 9. Similar to a Cornish pasty but containing a sweet filling at one end, how is this Bedfordshire dish known? Bedfordshire Clanger 10. What is "Scouse", a favourite dish in Liverpool? A Lamb (or Beef) stew 11. Where does the potato pancake known as Boxty originate? Ireland 12. Which Cheshire town host the annual International Cheese Awards? Nantwich 13. What filling would be traditionally used to make a Cottage Pie? (Minced) Beef 14. In which English county is Bakewell, home of the famous pudding? Derbyshire 15. On a traditional Cornish cream tea, what is put on the scone first, jam or cream? Jam 16. What food is the County Cork town of Clonakilty best known for? Black Pudding 17. In what part of London did the dish of Jellied Eels originate? East End 18. What town in Greater Manchester gives its name to a small round cake made from flaky pastry and filled with Currants? Eccles 19. -

Behind the Bar Pintxos Charcuteria Fish Meat

BOOK OPEN DAILY MON-SUN ONLINE www.salthousetapas.co.uk 12pm-10.30pm BEHIND THE BAR MEAT VEGETABLES GIN BAR Red Sangria Jug £16.95 Glass £6.50 Stornoway black pudding, confit lamb shoulder, Potato tortilla served with aioli £5.95 Bombay London Dry Hampshire £3.80 White Sangria Jug £16.95 Glass £6.50 caramelised onions, quail egg, jus £7.95 Bombay Sapphire (n) Hampshire £3.80 Rose Sangria Jug £16.95 Glass £6.50 Fried bravas potatoes, chunky White Cava Sangria Glass £7.00 Fillet of beef, bone marrow galette, tomato sauce, aioli £5.50 Bosford Rose London £3.80 Rose Cava Sangria Glass £7.00 oyster mushroom, jus £10.95 Whitley Neill Pan fried padron peppers, Rhubarb & Ginger Liverpool £4.00 Selection of Sherries from £4.00 smoked maldon salt £5.95 Chorizo sausage, romesco, fried egg, Larios 12 Spain £4.00 matchstick fries (n) £6.95 Salt House hummus, pomegranate PINTXOS Hendricks Scotland £4.00 & mint pesto, maple caramelised onions, Ampersand Mango & Chilli Spain £4.00 Sweet pickled Guindillas chillies £3.50 Sautéed baby chorizo with honey £5.95 crisp bread £5.95 Gin Mare Spain £4.30 Gordal olives, virgin oil, sea salt £3.95 12oz Pork chop, sobrasada romesco, Deep fried Monte Enebro goats cheese, chilli jam, apple salad £8.50 Boe Passionfruit Scotland £4.30 Salted roasted valencian almonds (n) £3.50 mojo verde (n) £8.95 Santamania Barrel Aged (n) Spain £4.30 Chicory & pear salad, goats cheese mousse, Toast with tomato £2.95 Slow roast chicken, sautéed Pernod wild mustard & walnut dressing (n) £5.95 Liverpool Gin (add manchego for 50p) mushrooms, -

Sizzlethe American Culinary Federation Quarterly for Students of Cooking

SPRING 2014 sizzleTHE AMERICAN CULINARY FEDERatION QUARTERLY FOR STUDENTS OF COOKING develop vegetable explore the rediscovery business skills cuisine of England menu trend sizzle features The American Culinary Federation NEXT Quarterly for Students of Cooking 16 Minding Your Own Publisher IssUE American Culinary Federation, Inc. Business Skills • Chefs reveal their best career-beginning Editor-in-Chief Beyond cooking, plan to learn as much as you can decisions. Jody Shee about spreadsheets, profit-and-loss statements, math, • Learn the latest snack trends. Senior Editor computer programs and marketing in order to succeed. • Discover what it takes to Kay Orde 22 Veggie Invasion run a food truck. Senior Graphic Designer David Ristau Vegetables are becoming increasingly important on restaurant menus, especially as variety expands Graphic Designer and consumers become more health-conscious. Caralyn Farrell Director of Communications 28 Food Companies Hire Chefs Patricia A. Carroll Discover why the employee turnover rate is so low among chefs who work in corporate Contributing Editors positions for food manufacturers. Rob Benes Suzanne Hall Ethel Hammer Karen Weisberg departments 16 22 28 Direct all editorial, advertising and subscription inquiries to: American Culinary Federation, Inc. 4 President’s Message 180 Center Place Way ACF president Tom Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC, discusses seizing all opportunities. St. Augustine, FL 32095 (800) 624-9458 [email protected] 6 Amuse-Bouche Student news, opportunities and more. Subscribe to Sizzle: www.acfchefs.org/sizzle 8 Slice of Life For information about ACF Jennifer Heggen walks us through a memorable day in her internship as pastry commis certification and membership, at Thomas Keller Restaurant Group’s Bouchon Bistro/Bakery in Yountville, Calif. -

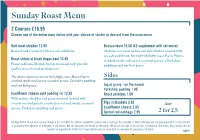

Sunday Roast Menu

Sunday Roast Menu 2 Courses £16.95 Choose one of the below main dishes with your choice of starter or dessert from the main menu. Half roast chicken 12.95 Banyan feast 16.50 (£3 supplement with set menu) Roasted and seasoned with sea salt and thyme. Medium rare roast sirloin and half chicken roasted with sea salt and thyme. Served with fluffy roast Maris Pipers, Roast sirloin of black Angus beef 13.95 crushed swede and carrot, seasonal greens, 2 Yorkshire From traditional British breeds to consistently provide puddings and our best gravy. quality meat. Served medium rare. The above roasts are served with fluffy roast Maris Pipers, Sides crushed swede and carrot, seasonal greens, Yorkshire pudding and our best gravy. Jug of gravy - on the house! Yorkshire pudding 1.00 Cauliflower cheese suet pudding (v) 12.95 Roast potatoes 1.00 With mature cheddar and grain mustard. Served with creamy mashed potato, crushed carrot and swede, seasonal Pigs in blankets 3.95 Any greens, Yorkshire pudding and gravy. Cauliflower cheese 2.95 Spiced red cabbage 2.95 2 for £5 (v) Vegetarian. If you have a food allergy or are sensitive to certain ingredients, please ask a manager for assistance. Due to the way our food is prepared it is not possible to guarantee the absence of allergens in our meals. Not all allergens are listed on the menu. We do not include ‘may contain’ information. Our menu descriptions do not include all ingredients. A full list of ingredients used in each dish is available for your peace of mind.