Mutual Banks Between Solidarity and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edited by Floriana Cerniglia and Francesco Saraceno C Erniglia

A European Public Investment Outlook EDITED BY FLORIANA CERNIGLIA AND FRANCESCO SARACENO C ERNIGLIA This outlook provides a focused assessment of the state of public capital in the major European countries and iden� fi es areas where public investment could AND contribute more to stable and sustainable growth. A European Public Investment Outlook brings together contribu� ons from a range of interna� onal authors from S diverse intellectual and professional backgrounds, providing a valuable resource ARACENO A European Public for the policy-making community in Europe to feed their discussion on public investment. The volume both off ers sector-specifi c advice and highlights larger areas which should be priori� zed in the policy debate (from transport to social ( capital, R&D and the environment). EDS ) Investment Outlook The Outlook is structured into two parts: the chapters of Part I respec� vely explore public investment trends in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Europe as a whole, and illuminate how the legacy of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis is one of insuffi cient public investment. Part II inves� gates some areas into which resources could be channelled to reverse the recent trend and provide European A E economies with an adequate public capital stock. UROPEAN The essays in this outlook collec� vely foster a broad approach to and defi ni� on of public investment, that is today more relevant than ever. Off ering up a � mely and clear case for the elimina� on of bias against investment in European fi scal rules, this outlook is a welcome contribu� on to the European debate, aimed both at P policy makers and general readers. -

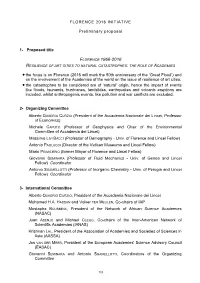

Preliminary Proposal to IAP

FLORENCE 2016 INITIATIVE Preliminary proposal 1- Proposed title FLORENCE 1966-2016 RESILIENCE OF ART CITIES TO NATURAL CATASTROPHES: THE ROLE OF ACADEMIES • the focus is on Florence (2016 will mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Great Flood’) and on the involvement of the Academies of the world on the issue of resilience of art cities; • the catastrophes to be considered are of ‘natural’ origin, hence the impact of events like floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, landslides, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are included, whilst anthropogenic events, like pollution and war conflicts are excluded. 2- Organizing Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO (President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Professor of Economics) Michele CAPUTO (Professor of Geophysics and Chair of the Environmental Committee of Accademia dei Lincei) Massimo LIVI BACCI (Professor of Demography - Univ. of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Antonio PAOLUCCI (Director of the Vatican Museums and Lincei Fellow) Mario PRIMICERIO (former Mayor of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Giovanni SEMINARA (Professor of Fluid Mechanics - Univ. of Genoa and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator Antonio SGAMELLOTTI (Professor of Inorganic Chemistry - Univ. of Perugia and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator 3- International Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO, President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei Mohamed H.A. HASSAN and Volker TER MEULEN, Co-chairs of IAP Mostapha BOUSMINA, President of the Network of African Science Academies (NASAC) Juan ASENJO and Michael CLEGG, Co-chairs of the Inter-American Network of Scientific Academies (IANAS) Krishnan LAL, President of the Association of Academies and Societies of Sciences in Asia (AASSA) Jos VAN DER MEER, President of the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC) Giovanni SEMINARA and Antonio SGAMELLOTTI, Coordinators of the Organizing Committee 1/3 4- Date 11 - 12 October 2016 5- Venue Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Palazzo Corsini, Rome 6- Structure of the meeting We propose the following structure of the meeting. -

Economic Theory and Its History

Economic Theory and its History This collection brings together leading economists from around the world to explore key issues in economic analysis and the history of economic thought. This book deals with important themes in economics in terms of an approach that has its roots in the works of the classical economists from Adam Smith to David Ricardo. The chapters have been inspired by the work of Neri Salvadori, who has made key contributions in various areas including the theory of production, the theory of value and distribution, the theory of economic growth, as well as the theory of renewable and exhaustible natural resources. The main themes in this book include production, value and distribution; endogenous economic growth; renewable and exhaustible natural resources; cap- ital and profits; oligopolistic competition; effective demand and capacity utiliza- tion; financial regulation; and themes in the history of economic analysis. Several of the contributions are closely related to the works of Neri Salvadori. This is demonstrated with respect to important contemporary topics including the sources of economic growth, the role of exhaustible resources in economic development, the reduction and disposal of waste, the redistribution of income and wealth, and the regulation of an inherently unstable financial sector. All contributions are brand new, original and concise, written by leading expo- nents in their field of expertise. Together this volume represents an invaluable contribution to economic analysis and the history of economic thought. This book is suitable for those who study economic theory and its history, political economy and philosophy. Giuseppe Freni is Professor of Economics at the University of Naples Parthenope, Italy. -

Excerpt of the Book

Techno-scientific platforms are a mode of interaction between different EURO-PLATFORMS: actors within a common scientific area and with shared technological SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND ECONOMY interests related to the economy and society. Grouping together these A crucial connection for Italy relations, not always formally or institutionally, has generated a «system» of cases that are difficult to put within a framework, but are of growing importance and require an analysis of the connections between political edited by economy and techno-science in consolidating profiles and perspectives Alberto Quadrio Curzio for the future of Europe. If we take CERN as an example, its techno- Marco Fortis and Alberto Silvani logical infrastructure, its governance and the support of its multi-stat- utory scientific community, we find an evident need for clarifying what economic-organizational model should be implemented to provide the project paradigms. The same holds true for the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, the European Space Agency and for lesser known, but no less important entities like the hub for data science and artificial intelligence. «Horizon Europe», the new framework programme of the European Commission and European Parliament, provides a perspective which is crucial in defining new initiatives. Alberto Quadrio Curzio is Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Università Cattolica, President Emeritus of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and Chairman of the Scientific Committee at Fondazione Edison. Marco Fortis teaches Industrial Economics and Foreign Trade at Università Cattolica. He is Vice Chairman and Director at Fondazione Edison where he is also Vice Chairman of the Scientific Committee. Alberto Silvani was the Research Director of CNR on the themes of research evaluation and technology transfer, and an Expert for the Eu- ropean Commission. -

List of Authors

List of Authors Editors Marco Fortis is the Director of the Department of Economic Studies of Edison and contract Professor of Industrial Economics and Foreign Trade at the Faculty of Political Sciences of Catholic University (Milan) since 1989. He is a member of the Scientific Committee of the Research Centre in Economic Analysis (CRANEC) of Catholic University (Milan), a member of the Scientific Committee and Vice-President of the Fondazione Edison, and Vice President of the Fondazione Guido Donegani. His publications include numerous books and articles in books, journals, and newspapers on the subjects of Italian economy, industry and local production systems, technology, development and international trade. His main books include: “Prodotti di base e cicli economici” (Il Mulino, 1988, Iglesias Prize winner), “Il made in Italy” (Il Mulino, 1998), “Le imprese multi utility” (Il Mulino, 2001), and “Le due sfide del made in Italy: globalizzazione e innovazione” (Il Mulino, 2005). With Alberto Quadrio Curzio he edited “Il made in Italy oltre il 2000” (Il Mulino, 2000), “Le liberalizzazioni e le privatizzazioni dei servizi pubblici locali” (Il Mulino, 2000), “Il gruppo Edison 1883-2003. Profili economici e societari (Il Mulino, 2003), “Industria e distretti. Un paradigma di perdurante competitività italiana” (Il Mulino, 2006), and “Valorizzare un’economia forte. L’Italia e il ruolo della sussidiarietà” (Il Mulino, 2007). [email protected] Alberto Quadrio Curzio is Professor of Political Economy, Dean of the Faculty of Political Sciences and Director of the Research Centre in Economic Analysis (CRANEC), Catholic University (Milan). He is Academic Secretary of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, chief editor of the journal “Economia Politica”, il Mulino, and on the Scientific Committee of other journals among which include “Structural Change and Economic Dynamics” and “Journal of Policy Modelling”. -

November 2020 ALBERTO QUADRIO CURZIO He Is Presently Emeritus

November 2020 ALBERTO QUADRIO CURZIO He is presently Emeritus Professor of Political Economy at Università Cattolica, Milan, where he was full professor of Political Economy from 1976 to 2010 and Dean of the Faculty of Political Science from 1989 to 2010. In 1977 he founded the Research Center of Economic Analysis and International Economic Development (CRANEC); he was its Director from 1977 to 2010 and is currently the Chairman of its Academic Board. President Emeritus of Lincei National Academy, Member of the Lincei Academy since 1996, President of the Class of Moral, Historical and Philological Sciences since 2009 and President from 2015 to 2018. Since 2020 he is President of the International Balzan Prize Foundation and he is member of the Executive Board of the same Foundation since 2006. Since 2009 he is President of the Joint Commission between the Balzan Foundation, the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences and vice-President since 2014. After obtaining his undergraduate degree from Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore, Milan, and undertaking research at St. John’s College, Cambridge, he held teaching positions at the University of Cagliari (1965) and then at the Univer- sity of Bologna (1968), where he became a tenured track professor (1972) and Dean of the Faculty of Political Science till 1975. He was the Italian representative for Economists at the National Research Council (CNR), President of the Istituto Lombardo and President of SIE, the Italian Association of Economists. He is member of the Royal Economic Society (UK) and of the Academia Europaea. He was a member of the Advisory Board of the Centre for Financial History, University of Cambridge (UK, 2013). -

CSP CV Quadrio Curzio Alberto EN

Alberto Quadrio Curzio Curriculum vitae Alberto Quadrio Curzio CURRICULUM VITAE page 1 of 5 Alberto Quadrio Curzio Curriculum vitae Alberto Quadrio Curzio Professional experience CURRENTLY Emeritus Professor University of the Sacred Heart, Milan Emeritus Professor of Political Economics Emeritus Chairman Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei Chairman of the Scientific Committee Economic Analysis and International Economic Development Research Centre – CRANEC of the Catholic University Chairman International Balzan Prize Foundation Chairman of the Scientific Committee Edison Foundation Director "Economia politica. Journal of Analytical and Institutional economics" Founded by him in 1984 and currently co-published by Il Mulino and Spinger Member of the Executive Board Aspen Institute Italy Member of several bodies “Il Mulino” Publishing Company and Association, Bologna page 2 of 5 Alberto Quadrio Curzio Curriculum vitae Education 1961 Degree in Politics Catholic University of Milan Score 110/110 cum laude, thesis “Savings in the theory of economic well-being”, supervisor Siro Lombardini. 1962 - 1963 Specialisation University of Cambridge and St. John’s College Specialisation with scholarship from the Italian Ministry of Education. 1963 - 1967 Voluntary assistant Catholic University of Milan Voluntary assistant to the Chair of Econometrics held by Prof. Luigi Pasinetti at the Catholic University and research for the professorship in Political Economics which he obtained in 1968. Academic and Scientific Career 1965 - 1968 University of Cagliari Tenured Professor in the Faculty of Law. 1968 - 1975 University of Bologna Lecturer in various economic disciplines at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences from 1 November 1968 to 31 October 1974; Visiting professor in 1972; Dean of the Faculty of Political Sciences for the academic year 1974-75.