Murder in Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Directory

Guest Directory Guest Directory AM Solar rev. 12/13/20 Table of Contents ACCOMMODATIONS………………………………………………………………………….…3 VALLEY RIVER INN………………………………………………………………………………………..…..5 Map of Valley River Area…………………………………………………………………………………6 SweetWaters Hours of Operation……………………………………………………………………7 VILLAGE INN……………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Map of Shoppes at Gateway……………………………………………………………………………9 Map of Nearby AM Solar……………………………………………………………………………….10 CAR RENTALS………………………………………………………………………………………11 THINGS TO DO IN EUGENE/SPRINGFIELD……………………………………………12 RESOURCES………………………………………………………………………………………..13 2 Guest Directory AM Solar rev. 12/13/20 3 Guest Directory AM Solar rev. 12/13/20 ACCOMMODATIONS AM Solar has a corporate relationship with the Valley River Inn and the Village Inn. If you intend to stay at either of those hotels, be sure to say you are with AM Solar so that you will receive the negotiated room rate. Keep in mind that whenever possible, scheduling in advance will more likely ensure a better room rate. Receiving a discounted room rate is contingent on hotel availability and one should be mindful of local events that might pose difficulty reserving a room at late notice. The most common times that discounts are not available are the second week of June (NCAA Track & Field, followed by UO Graduation) and in the fall, home Duck football games. It should be noted that Eugene & Springfield occasionally hosts the Olympic Trials for Track & Field (June - July) and discounts/availabilities may not be available during that time. All of the accommodations listed below are pet friendly. Valley River Inn 1000 Valley River Way Eugene, OR 97401 541-743-1000; 800-543-8266 http://www.valleyriverinn.com/ Village Inn 1875 Mohawk Blvd. Springfield, OR 97477 541-747-4546; 800-327-6871 http://springfieldvillageinn.com 4 Guest Directory AM Solar rev. -

Renovation Last Fall

Going Places Macerich Annual Report 2006 It’s more than the end result—it’s the journey. At Macerich®, what’s important isn’t just the destination. It’s the bigger picture, the before and after...the path we take to create remarkable places. For retailers, it’s about collaboration and continual reinvestment in our business and theirs. For the communities we serve, it’s about working together to create destinations that reflect their wants and needs. For investors, it’s about long-term value creation stemming from a clear vision. For consumers, it’s about the total experience our destinations deliver. 0 LETTER TO STOCKHOLDERS Letter to Our Stockholders Macerich continued to create significant value in 2006 by elevating our portfolio and building a sizeable return for our stockholders. Total stockholder return for the year was 33.9%, contributing to a three-year total return of 121.5% and a five-year total return of 326.2%. In 2006, the company increased dividends for the 13th consecutive year. As a company that considers its pipeline a tremendous source of strength BoulderTwenty Ninth is a prime Street example is a prime of howexample 2006 of was how indeed 2006 awas remarkable indeed a yearremark of - and growth, Macerich reached an important milestone in 2006 with the buildingable year netof building asset value net for asset Macerich. value for We Macerich. also completed We also the completed redevelop the- re- opening of Twenty Ninth Street in Boulder, Colorado. Not only is this a mentdevelopment of Carmel of CarmelPlaza in Plaza Northern in Northern California, California, another another excellent excellent model of model terrific new asset in an attractive, affluent community—it represents a sig- valueof value creation, creation, where where we we realized realized a significant a significant return return on onour our investment. -

THE MACERICH COMPANY (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) MARYLAND 95-4448705 (State Or Other Jurisdiction (I.R.S

Macerich Wrap 09 Proof 7 | 03.24.10 Page MacerichMacerich Wrap Wrap09 09Proof Proof 7 | 03.24.10 7 | 03.24.10 Page Page MacerichMacerich Wrap Wrap 09 09 CoverProof Art 7 || 03.24.1003.24.10 BackPage MacerichMacerich Wrap Wrap 09 09 ProofCover 7 Art| 03.24.10 | 03.24.10 Page Page This will be the inside back cover. ThisThis is is the the back back cover cover >> Spine is set at 0.375” wide. CoverThis Pageis the front cover. b 1 5 PBCover a PB Macerich 2009 Annual Report Financial Highlights Corporate Information (all amounts in thousands, except per share and per square foot amounts) 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Principal Outside Counsel Macerich Website Stock Exchange Listing Operating Data O’Melveny & Myers LLP For an electronic version of this New York Stock Exchange Los Angeles, California annual report, our SEC filings Symbol: MAC Total revenues $ 805,654 $ 880,871 $ 800,842 $ 737,311 $ 648,636 and documents relating to The common stock of the Company is listed Shopping center and operating expenses $ 258,174 $ 281,613 $ 253,258 $ 230,463 $ 200,305 Independent Auditor corporate governance, please and traded on the New York Stock Exchange Management companies’ operating expenses $ 79,305 $ 77,072 $ 73,761 $ 56,673 $ 52,840 visit www.macerich.com. Deloitte & Touche LLP under the symbol “MAC.” The common stock REIT general and administrative expenses $ 25,933 $ 16,520 $ 16,600 $ 13,532 $ 12,106 Los Angeles, California Corporate Headquarters began trading on March 10, 1994, at a price of Net income (loss) available to common stockholders $ 120,742 $ 161,925 $ 64,131 $ 217,404 $ (93,614) $19 per share. -

Effective 5/4/08 Macy's West SMALL TICKET DEPARTMENTS Store/DC List As of May 4, 2008

Macy's West SMALL TICKET DEPARTMENTS Store/DC List as of May 4, 2008 Current Current New New DC Division Store Division Store DC Alpha Effective Name Number Name Number Name Code Mall Name / Store Name Address City State Zip Date Macy's Northwest 0001 MCW 0301 Tukwila TU SEATTLE (DOWNTOWN) Third and Pine Seattle WA 98181 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0002 MCW 0302 Tukwila TU NORTHGATE (WA) 401 NE Northgate Way Space 602 Seattle WA 98125 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0003 MCW 0303 Tukwila TU TACOMA 4502 South Steele #700 Tacoma WA 98409 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0004 MCW 0304 Tukwila TU WENATCHEE VALLEY 445 Valley Mall Pkwy E. Wenatchee WA 98802 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0005 MCW 0305 Tukwila TU BELLIS FAIR (BELLINGHAM) 50 Bellis Fair Pkwy Bellingham WA 98226 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0006 MCW 0306 Tukwila TU SPOKANE (DOWNTOWN) Main and Wall St Spokane WA 99201 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0008 MCW 0308 Tukwila TU SOUTH CENTER (WA) 500 Southcenter Mall Tukwila WA 98188 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0009 MCW 0309 Tukwila TU THREE RIVERS 331 Three Rivers Dr Kelso WA 98626 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0010 MCW 0310 Tukwila TU WALLA WALLA (DOWNTOWN) 54 East Main St Walla Walla WA 99362 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0011 MCW 0311 Tukwila TU COLUMBIA CENTER (WA) 1321 N.Columbia Center BLVD. Suite 400 Kennewick WA 99336 5/4/2008 Macy's Northwest 0012 MCW 0312 Tukwila TU NORTHTOWN (WA) N. -

List of Creditors

Yatsen Group of Companies Inc. and Other Applicants Identified in the Initial Order (collectively, “YGC”) List of Creditors Please note the following: 1. This list of creditors has been prepared from information contained in the books and records of YGC. All balances are as at December 31, 2020. 2. The amounts included in this list of creditors do not take into consideration any un-invoiced amounts, nor have the amounts been adjusted for any amounts that may also be receivable from creditors. 3. This list of creditors has been prepared without admission as to the liability for, or quantum of, any of the amounts shown. 4. To date, a claims procedure has not been approved by the Court, and creditors are NOT required to file a statement of account or proof of claim at this point in time. If, at a later date, a claims procedure is approved by the Court, all known creditors will be notified and claim forms will be posted to the Monitor's website. It is through such a claims procedure that creditor claims will be reviewed and determined. Page 1 of 5 Yatsen Group of Companies Inc., et. al. (collectively, "YGC") List of Creditors Please note the following: 1. This list of creditors has been prepared from information contained in the books and records of YGC. All balances are as at December 31, 2020. 2. The amounts included in this list of creditors do not take into consideration any un-invoiced amounts, nor have the amounts been adjusted for any amounts that may also be receivable from creditors. -

5Mar200719253705

Exhibit 99.2 5MAR200719253705 Supplemental Financial Information For the three and six months ended June 30, 2008 The Macerich Company Supplemental Financial and Operating Information Table of Contents All information included in this supplemental financial package is unaudited, unless otherwise indicated. Page No. Corporate overview ....................................................... 1-3 Overview .............................................................. 1 Capital information and market capitalization ................................... 2 Changes in total common and equivalent shares/units .............................. 3 Financial data .......................................................... 4-5 Supplemental FFO information .............................................. 4 Capital expenditures ...................................................... 5 Operational data ........................................................ 6-9 Sales per square foot ..................................................... 6 Occupancy ............................................................. 7 Rent................................................................. 8 Cost of occupancy ....................................................... 9 Balance sheet information ................................................. 10-12 Debt summary .......................................................... 10 Outstanding debt by maturity ............................................... 11-12 Development and Pipeline Forecast .......................................... -

Northbank Office Building

FOR LEASE 44 Club Road Suite 150 Eugene, Oregon Approximately 7,286 rentable square feet (can demise) Patio on the Willamette River Four restrooms (one contains a shower and lockers) Full kitchen On-site parking $1.67 per square foot including utilities through February 2016 The information in this package was gathered from sources deemed reliable, however Evans Elder & Brown makes no representation or warranty of the accuracy of the information. Any buyer or tenant considering a purchase or lease of this property should confirm any and all information relied upon in making the decision to purchase or lease prior to finalizing the transaction and bears the risk of all inaccuracies. Floor Plan ( " %6 Office space consists of open work areas, one large conference room, 4 rest rooms (one includes a shower), full kitchen, temperature controlled server room and bicycle storage. "%!#.@[email protected] Large windows provide 868C@U 868C@U 868C@U abundant natural light 868C@U 868C@U #' ## 868C@U and beautiful views of the 868C@U 868C@U 868C@U Willamete River from all work 868C@U areas. Unique, high quality finishes throughout. The information in this package was gathered from sources deemed reliable, however Evans Elder & Brown makes no representation or warranty of the accuracy of the information. Any buyer or tenant considering a purchase or lease of this property should confirm any and all information relied upon in making the decision to purchase or lease prior to finalizing the transaction and bears the risk of all inaccuracies. Interior The information in this package was gathered from sources deemed reliable, however Evans Elder & Brown makes no representation or warranty of the accuracy of the information. -

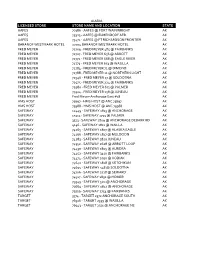

Licensed Store Store Name and Location State

ALASKA LICENSED STORE STORE NAME AND LOCATION STATE AAFES 70386 - AAFES @ FORT WAINWRIGHT AK AAFES 75323 - AAFES @ ELMENDORF AFB AK AAFES 75471 - AAFES @ FT RICHARDSON FRONTIER AK BARANOF WESTMARK HOTEL 22704 BARANOF WESTMARK HOTEL AK FRED MEYER 72709 - FRED MEYER 485 @ FAIRBANKS AK FRED MEYER 72727 - FRED MEYER 656 @ ABBOTT AK FRED MEYER 72772 - FRED MEYER 668 @ EAGLE RIVER AK FRED MEYER 72773 - FRED MEYER 653 @ WASILLA AK FRED MEYER 72784 - FRED MEYER 71 @ DIMOND AK FRED MEYER 72788 - FRED MEYER 11 @ NORTHERN LIGHT AK FRED MEYER 72946 - FRED MEYER 17 @ SOLDOTNA AK FRED MEYER 72975 - FRED MEYER 224 @ FAIRBANKS AK FRED MEYER 72980 - FRED MEYER 671 @ PALMER AK FRED MEYER 79324 - FRED MEYER 158 @ JUNEAU AK FRED MEYER Fred Meyer-Anchorage East #18 AK HMS HOST 75697 - HMS HOST @ ANC 75697 AK HMS HOST 75988 - HMS HOST @ ANC 75988 AK SAFEWAY 12449 - SAFEWAY 1813 @ ANCHORAGE AK SAFEWAY 15313 - SAFEWAY 1739 @ PALMER AK SAFEWAY 3513 - SAFEWAY 1809 @ ANCHORAGE DEBARR RD AK SAFEWAY 4146 - SAFEWAY 1811 @ WAILLA AK SAFEWAY 74265 - SAFEWAY 1807 @ ALASKA EAGLE AK SAFEWAY 74266 - SAFEWAY 1817 @ MULDOON AK SAFEWAY 74283 - SAFEWAY 1820 JUNEAU AK SAFEWAY 74352 - SAFEWAY 2628 @ ABBOTT LOOP AK SAFEWAY 74430 - SAFEWAY 1805 @ AURORA AK SAFEWAY 74452 - SAFEWAY 3410 @ FAIRBANKS AK SAFEWAY 74474 - SAFEWAY 1090 @ KODIAK AK SAFEWAY 74640 - SAFEWAY 1818 @ KETCHIKAN AK SAFEWAY 74695 - SAFEWAY 548 @ SOLDOTNA AK SAFEWAY 74706 - SAFEWAY 2728 @ SEWARD AK SAFEWAY 74917 - SAFEWAY 1832 @ HOMER AK SAFEWAY 79549 - SAFEWAY 520 @ ANCHORAGE AK SAFEWAY 79664 - SAFEWAY 1812 @ ANCHORAGE -

3Feb201415105791 24Mar201406004217

Exhibit 99.2 3FEB201415105791 Supplemental Financial Information For the three months ended March 31, 2014 24MAR201406004217 The Macerich Company Supplemental Financial and Operating Information Table of Contents All information included in this supplemental financial package is unaudited, unless otherwise indicated. Page No. Corporate Overview ....................................................... 1-3 Overview .............................................................. 1 Capital Information and Market Capitalization ................................... 2 Changes in Total Common and Equivalent Shares/Units ............................ 3 Financial Data .......................................................... 4-9 Unaudited Pro Rata Statement of Operations .................................... 5 Notes to Unaudited Pro Rata Statement of Operations ............................. 6 Unaudited Pro Rata Balance Sheet ........................................... 7 Supplemental FFO Information .............................................. 8 Capital Expenditures ...................................................... 9 Operational Data ........................................................ 10-25 Sales Per Square Foot ..................................................... 10 Sales Per Square Foot by Property Ranking ..................................... 11-15 Occupancy ............................................................. 16 Average Base Rent Per Square Foot ........................................... 17 Cost of Occupancy ...................................................... -

Creating the | | Form 10-K Form 10-K Future

CELEBRATING THE PAST 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT CREATING THE | | FORM 10-K FORM 10-K FUTURE 2015 ANNUAL REPORT | FORM 10-K 401 WILSHIRE BOULEVARD, SUITE 700 SANTA MONICA, CA 90401-1452 | 310.394.6000 | WWW.MACERICH.COM | NYSE:MAC FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (All amounts in thousands, except share data and per square foot amounts) 2 OPERATING DATA 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 Total Revenues $1,288,149 $1,105,247 $1,029,475 $797,517 $684,744 Shopping center and operating expenses $379,815 $353,505 $329,795 $251,923 $213,832 Management companies’ operating expenses $92,340 $88,424 $93,461 $85,610 $86,587 REIT general and administrative expenses $29,870 $29,412 $27,772 $20,412 $21,113 Gain (loss) on remeasurement, sale or write down of assets, net $400,337 $1,496,576 ($26,852) $228,690 ($22,037) Net income attributable to the Company $487,562 $1,499,042 $420,090 $337,426 $156,866 Net income per share attributable to common stockholders - $3.08 $10.45 $3.00 $2.51 $1.18 diluted OTHER DATA 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 Regional shopping centers portfolio occupancy 96.1% 95.8% 94.6% 93.8% 92.7% Regional shopping centers portfolio sales per square foot $635 $587 $562 $517 $489 Distributions declared per common share $6.63 $2.51 $2.36 $2.23 $2.05 BALANCE SHEET DATA MACERICH 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 Cultivating premier shopping destinations by reinventing them over time to create a current portfolio thatSINCE is both rich in history and modern 1964 innovation. -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Now Open! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Now Open! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Now Open! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Now Open! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Now Open! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Now Open! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Now Open! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Now Open! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Now Open! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Now Open! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MCCAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Now Open! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMENADE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Now Open! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMENADE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Now Open! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Now Open! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Now Open! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Now Open! 2940 AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS AT LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N Now Open! 2419 AZ MESA SUPERSTITION SPRINGS MALL 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE Now Open! 2846 AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD Now Open! 1480 AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD Now Open! 2902 AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 Now Open! 1130 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHOPPING CENTER 3501 E BROADWAY Now Open! -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address 1831 AK Anchorage 5Th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5Th Ave

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address 1831 AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave. 2131 AL Huntsville Madison Square 5901 University Dr 219 AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall 2840 AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall 2956 AL Prattville High Point Town Center 550 Pinnacle Place 2875 AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Town Center 22500 Towncenter Ave 2869 AL Trussville Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Square 1786 AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 MacFarland Blvd East 2709 AR Fayetteville Northwest Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr 1961 AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave. 2835 AR Jonesboro Mall at Turtle Creek 300 E Highland Dr Ste 516 2914 AR Little Rock Shackleford Crossing 2600 S Shackleford. Rd. 663 AR North Little Rock McCain Shopping Center 3929 McCain Blvd Ste 500 2879 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hills Promenade 2202 Bellview Rd. 2936 AZ Casa Grande Promenade at Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy 251 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center 2842 AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerstone 13333 W Mcdowell Rd. 2940 AZ Lake Havasu City Shops at Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N 2419 AZ Mesa Superst'n Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave. 2846 AZ Phoenix Ahwatukee Foothills 5050 E Ray Rd. 1480 AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd. 90 AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd. 2913 AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz 2955 CA Antioch Orchard at Slatten Ranch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd. 1417 CA Arcadia Westfield Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave.