Development of Mapping of Living in Lebanon 1995-2004 UNDP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

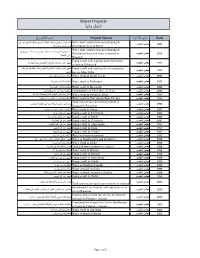

Water Projects ﻣﺎﺋﯾﺔ أﺷﻐﺎل

Water Projects أشغال مائية Date إٍسم اﻹدارة Project Name إسم المشروع & Water tank construction and pumping بناء خزان ارضي وتمديد شبكات توزيع وخطوط دفع وجر في 1997 مجلس الجنوب distribution lines in Dweir قرى الدوير وجوارها Water tank construction and pumping & بناء خزان علوي وتمديد خطوط دفع وجر وشبكات توزيع في 1995 مجلس الجنوب distribution lines and water networks in وادي النبطية Nabatieh Equip a well with a pump and chlorination 1997 مجلس الجنوب تجهيز البئر بمعدات الضخ والتعقيم في بلدة الهبارية system in Hebariyeh Equip a well and construction of a pumping تجهيز البئر بمعدات الضخ والتعقيم وانشاء خط دفع في بلدة 1997 مجلس الجنوب line in Jabin Town الجبين 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Majdl Selem اشغال مائية في مجدل سلم 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Mahrouna اشغال مائية في محرونة 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Baysarieh اشغال مائية في البيسارية 1995 مجلس الجنوب Continuation of Fakherdine Velley's استكمال مياه آبار وادي فخرالين 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Nabatieh Tahta اشغال مائية في النبطية التحتا )محدلة الدباغة( 1996 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Deir Anoun Rass EL Ain اشغال مائية في دير قانون رأس العين Tank construction and water network in 1996 مجلس الجنوب بناء قصر مائي وشبكة مائية في قعقعية الصنوبر Qaaqayieh Sanawbar 1997 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Dweir اشغال مائية في الدوير وجوارها 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Teir Harfa تجهيز بئر طير حرفا 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Debel تجهيز بئر وخط دفع في دبل 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Hebariyeh تجهيز بئر في الهبارية 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Alma shaab تجهيز بئر في علما -

Swiss Solidar Needs Assessment Report Nabatieh

Swiss Solidar Needs Assessment Report Nabatieh and Jezzine Districts, Southern Lebanon 12 – 16 August 2013 Photo: Meeting with a group of refugees in Doueir municipality, Nabatieh District A – Methodology Swiss Solidar undertook a multi-sectoral needs assessment in August 2013 to assess the humanitarian needs of Syrian refugees residing in Nabatieh and Jezzine Districts in Southern Lebanon.1 Prior to undertaking its field assessment, Solidar undertook a detailed documentation review, including other recent needs assessment reports, strategy documents, NGO position papers and relevant standards. Based on feedback we received from other agencies, UNHCR and government sources, Solidar identified potential gaps in the provision of Shelter, WASH, Protection and Non Food Item (particularly winterisation) assistance in Nabatieh and Jezzine governorates in South Lebanon. A reconnaissance visit to Nabatieh to meet with the Head of the Union of Municipalities and two Heads of Municipalities was then undertaken on 25 July 2013 to confirm the need for Solidar to extend its operations to these locations. Feedback from these meetings demonstrated that there were indeed significant gaps in the assistance being provided to refugees, and Solidar made plans for a more detailed needs assessment. The assessment was undertaken over 5 days from 12-16 August 2013. In addition to Nabatieh, Solidar also included Jezzine District in the assessment as, although there were lower numbers of refugees, the extent of formal assistance was very low. The purpose of the assessment was to assess the situation of Syrian refugees in relation to shelter, livelihoods, WASH, winterisation and protection. Three teams from the local area were recruited and trained for the assessment, overseen by an Assessment Coordinator. -

Expanded Programme of Immunization Study

Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 Expanded Programme on Immunization District-Based Immunization Coverage Cluster Survey 1 Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 Acknowledgment Special acknowledgment goes to the Director General of the Ministry of Public Health, Dr. Walid Ammar for his guidance, and Dr Randa Hamadeh, head of the Primary Health Care department for facilitating the process of the study. Particular thanks goes to Dr. Gabriele Riedner, WHO Representative in Lebanon Country Office, for her unconditional support and Dr. Alissar Rady for her technical guidance all through the design and implementation process, and the country office team as well as the team at WHO Regional Office. The Expanded Programme on Immunization, district-based immunization coverage cluster survey, would not have been possible without the generous financial support of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the World Health Organization. This EPI cluster survey was conducted by the Connecting Research to Development center, contracted by and under the guidance of WHO and with the overall supervision of the MOPH team. 2 Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures......................................................................................................................................... -

Saida and Jezzine: South 1 Electoral District Pre-Elections Dynamics and Atmospherics Conflict Analysis Report – April 2018

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Saida and Jezzine: South 1 Electoral District Pre-elections Dynamics and Atmospherics Conflict Analysis Report – April 2018 Supported by: This report was written by an independent researcher as part of a conflict analysis consultancy for the UNDP “Peace Building in Lebanon” Project to inform and support UNDP Lebanon programming, as well as interventions from other partners in the framework of the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP). Through these reports, UNDP is aiming at providing quality analysis to LCRP Partners on the evolution of local dynamics, highlighting how local and structural issues have impacted and interacted with the consequences of the Syrian crisis in Lebanon. This report has been produced with the support of the Department for International Development (UKDFID). For any further information, please contact directly: Tom Lambert, UNDP Social Stability Sector Coordinator at [email protected] and Joanna Nassar, UNDP “Peace Building in Lebanon” Project Manager at [email protected] Report written by Bilal Al Ayoubi The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNDP, nor its partners. UNDP © 2018 All rights reserved. Cover Photo © UNDP Lebanon, 2018 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Saida and Jezzine: South 1 Electoral District Pre-elections Dynamics and Atmospherics Conflict Analysis Report – April 2018 Supported by: 1 Saida and Jezzine: South 1 Electoral District Pre-elections Dynamics and Atmospherics Conflict -

D D D L'8:L D

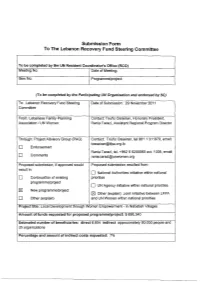

Submission Form To The Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Committee To be completed by the UN Resident Coordinator's Office (RCO) Meeting No: Date of Meeting: Item No: Programme/project: (To be completed by the Participating UN Organisation and endorsed by SC) To: Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Date of Submission: 29 November 2011 Committee From: Lebanese Family Planning Contact: Toufic Osseiran, Honorary President, Association I UN Women Rania Tarazi, Assistant Regional Program Director Through: Project Advisory Group (PAG) Contact: Toufic Osseiran, tel 961 1 311978, email: [email protected] D Endorsement Rania Tarazi, tel. +962 6 5200060 ext. 1008, email: D Comments [email protected] Proposed submission, if approved would Proposed submission resulted from: result in: D National Authorities initiative within national D Continuation of existing priorities programme/project D UN Agency initiative within national priorities l'8:l New programme/project l'8:] Other (explain): Joint initiative between LFPA D Other (explain) and UN Women within national priorities Project title: Local Development through Women Empowerment- in Nabatieh Villages Amount of funds requested for proposed programme/project: $ 698,340 Estimated number of beneficiaries: direct 6,604 indirect approximately 90,000 people and 35 organizations Percentage and amount of indirect costs requested: 7% Background The project was jointly developed by UN Women and the Lebanese Family Planning Association (LFPA). UN Women, an non-resident agency in Lebanon, conducted a gender needs assessment in April 2011 to identify entry points for its technical support to national organizations within its mandate of gender equality. In addition to identifying potential partners, the gender needs assessment has shown that women have not been systematically included in the recovery and reconstruction efforts in Lebanon. -

Informing Targeted Host Community Programming in Lebanon

INFORMING TARGETED HOST COMMUNITY PROGRAMMING IN LEBANON SECONDARY DATA REVIEW SEPTEMBER 2014 Host Community Vulnerabilities in Lebanon: Secondary Data Review – September 2014 SUMMARY As the Syria conflict enters its fourth year, the number of refugees settling in neighbouring countries continues to rise. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an estimated 1,055,393 registered refugees from Syria reside in Lebanon.1 The influx of refugees from Syria, which constitutes 20 per cent of the total population living in Lebanon, has had a tremendous impact on the demographic, socioeconomic and security situation in the country. The 2014 Syria Regional Response Plan (RRP6) reported that 86 per cent of refugees have relocated to communities hosting 66 per cent of the most vulnerable Lebanese populations.2 The presence of refugees has affected the resilience of host communities, particularly in terms of accessing basic services and public infrastructure, as well as social cohesion within communities already affected by sectarian divisions. This secondary data review report was conducted during the inception phase of an assessment carried out by REACH Initiative in partnership with the United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in 2014. This larger study aims to inform host community programming in Lebanon through the participatory identification of vulnerabilities and factors that undermine community resilience and social cohesion. In terms of information management, this assessment hopes to fill a major information gap in regards to community vulnerabilities as they pertain to refugee and host community populations. This report provides a review of secondary data and information available on the social, economic and political impact of the refugee influx on host communities with a specific focus on the principal vectors of tension within these communities in the context of the Syria crisis. -

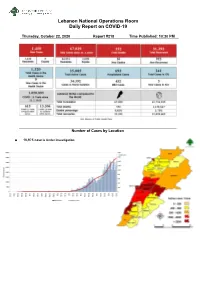

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Thursday, October 22, 2020 Report #218 Time Published: 10:30 PM Number of Cases by Location • 10,975 case is Under investigation Beirut 60 Chouf 43 Kesrwen 98 Matn 151 Ashrafieh 9 Anout 1 Ashkout 1 Ein Alaq 1 Ein Al Mreisseh 1 Barja 6 Ajaltoun 2 Ein Aar 1 Basta Al Fawka 1 Barouk 1 Oqaybeh 1 Antelias 3 Borj Abi Haidar 2 Baqaata 1 Aramoun 1 Baabdat 3 Hamra 1 Chhim 6 Adra & Ether 1 Bouchrieh 1 Mar Elias 3 Damour 1 Adma 1 Beit Shabab 2 Mazraa 3 Jiyyeh 2 Adonis 3 Beit Mery 1 Mseitbeh 2 Ketermaya 2 Aintoura 1 Bekfaya 2 Raouche 1 Naameh 5 Ballouneh 3 Borj Hammoud 9 Ras Beirut 1 Niha 3 Fatqa 1 Bqennaya 1 Sanayeh 2 Wady Al Zayne 1 Bouar 2 Broummana 2 Tallet El Drouz 1 Werdanieh 1 Ghazir 3 Bsalim 1 Tallet Al Khayat 1 Rmeileh 1 Ghbaleh 1 Bteghrine 1 Tariq Jdeedeh 4 Saadiyat 1 Ghodras 2 Byaqout 1 Zarif 1 Sibline 1 Ghosta 3 Dbayyeh 3 Others 27 Zaarourieh 1 Hrajel 1 Dekwene 12 Baabda 101 Others 9 Ghadir 2 Dhour Shweir 1 Ein El Rimmaneh 8 Hasbaya 6 Haret Sakher 6 Deek Al Mahdy 2 Baabda 4 Hasbaya 1 Kaslik 3 Fanar 4 Bir Hassan 1 Others 5 Sahel Alma 7 Horch Tabet 1 Borj Al Brajneh 17 Byblos 25 Sarba 5 Jal El Dib 3 Botchay 1 Blat 1 Kfardebian 1 Jdeidet El Metn 2 Chiah 6 Halat 1 Kfarhbab 1 Mansourieh 2 Forn Al Shebbak 3 Jeddayel 1 Kfour 3 Aoukar 3 Ghobeiry 3 Monsef 1 Qlei'aat 1 Mazraet Yashouh 3 Hadat 12 Ras Osta 1 Raasheen 2 Monteverde 2 Haret Hreik 5 Others 20 Safra 2 Mteileb 3 Hazmieh 4 Jezzine 12 Sehaileh 1 Nabay 1 Loueizy 1 Baysour 1 Tabarja 6 Naqqash 3 Jnah 2 Ein Majdoleen 1 Zouk Michael 1 Qanbt -

Lebanon: Aid Security Insight October 2020

Lebanon: Aid Security Insight October 2020 In the afternoon of 4 August 2020, two explosions occurred at Beirut’s seaport causing over 180 deaths and injuring more than 6,000 people. The blast destroyed several major hospitals, some 20 clinics, and over 120 schools. The blast happened against a background of a deep political, financial, and economic crisis. The coping capacity of services were already stretched, compounded by the spread of COVID-19. Today, there are a wide range of humanitarian needs in Lebanon, a country where refugees make up 30% of the population. The number of daily COVID-19 infections rose sharply at the end of August and has been steadily climbing since then. This document provides information on safety and security concerns aid agencies responding to the wide range of needs in the country should consider in their duty of care responsibilities towards their staff and local partners. The analysis is based on security incidents and concerns shared by ten aid agencies through the Aid in Danger project. It provides a unique insight into the environment in which aid agencies work. It is based on data for January 2015 and June 2020. Overall there has been no significant change in humanitarian access in Lebanon so far. This document describes the security trends affecting aid observed over the past five years. Reported concerns affecting aid delivery in Lebanon • Aid delivery disruption: Common in the past. Threatening behaviour by local individuals and beneficiaries towards NGO staff members, notably over beneficiary lists, and aid contracts and activities. • Operational space: Most frequently reported issue in 2020. -

Syria Refugee Response

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE Distribution of MoPH network and UNHCR Health Brochure Selected PHC as of 6 October, 2016 Akkar Governorate, Akkar District - Number of syrian refugees : 99,048 Legend !( Moph Network Moph Network !< and UNHCR Dayret Nahr Health El-Kabir 1,439 Brochure ") UNHCR Health Brochure Machta Hammoud Non under 2,246 MoPH network 30221 ! or under 30123 35516_31_001 35249_31_001 IMC No partner Wadi Khaled health center UNHCR Health Al Aaboudiyeh Governmental center !< AAridet Sammaqiye !( 713 Aaouaainat Khalsa Brochure Cheikh Hokr Hokr Dibbabiye Aakkar 1 30216 Zennad Jouret Janine Ed-Dahri 67 Kfar 6 35512_31_001 6 Srar 13 !( Aamayer Kharnoubet Noun No partner 13,361 Barcha Khirbet Er Aakkar 8 Alaaransa charity center Most Vulnerable Massaaoudiye 7 Aarme Mounjez Remmane 386 Noura ! 29 25 13 Qachlaq Et-Tahta 35512-40-01 Localities Tall Chir 28 17 Hmayra No partner Cheikh Kneisset Hmairine Aamaret Fraydes ! 105 1,317 Srar Aakkar Cheikhlar Wadi Khaled SDC Qarha Zennad Aakkar Tall El-Baykat 108 7 Rmah 62 Aandqet !< Aakkar 257 Mighraq 33 Bire 462 Most Mzeihme Ouadi 49 401 17 44 Aakkar 11 El-Haour Kouachra 168 Baghdadi Vulnerable Haytla 636 1,780 Qsair Hnaider 30226 !( Darine 10 Aamriyet Aakkar 1,002 35229_31_001 124 Aakkar 35 Mazraat 2nd Most No partner Tall Aabbas Saadine Alkaram charity center - Massoudieh Ech-Charqi 566 En-Nahriye Kneisset Tleil Barde 958 878 Hnaider Vulnerable !< 798 35416-40-01 4 Ghazayle 1,502 30122 38 No partner ! 35231_31_001 Bire Qleiaat Aain Ez-Zeit Kafr Khirbet ")!( IMC Aain 3rd Most Aakkar Hayssa Saidnaya -

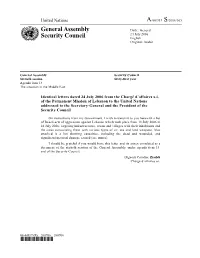

General Assembly Security Council Sixtieth Session Sixty-First Year Agenda Item 14 the Situation in the Middle East

United Nations A/60/953–S/2006/565 General Assembly Distr.: General 24 July 2006 Security Council English Original: Arabic General Assembly Security Council Sixtieth session Sixty-first year Agenda item 14 The situation in the Middle East Identical letters dated 24 July 2006 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council On instructions from my Government, I wish to transmit to you herewith a list of Israeli acts of aggression against Lebanon which took place from 18 July 2006 to 22 July 2006, targeting infrastructures, towns and villages with their inhabitants and the areas surrounding them with various types of air, sea and land weapons. Also attached is a list showing casualties, including the dead and wounded, and significant material damage caused (see annex). I should be grateful if you would have this letter and its annex circulated as a document of the sixtieth session of the General Assembly, under agenda item 14, and of the Security Council. (Signed) Caroline Ziadeh Chargé d’affaires a.i. 06-44187 (E) 260706 260706 *0644187* A/60/953 S/2006/565 Annex to the identical letters dated 24 July 2006 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Principal places targeted and damage sustained from 18 July 2006 to 8 a.m. on 19 July 2006 • Bridges targeted – Internal bridge of Al-Ghaziye (completely -

“Our Homes Are Not for Strangers” Mass Evictions of Syrian Refugees by Lebanese Municipalities

HUMAN “Our Homes Are Not RIGHTS for Strangers” WATCH Mass Evictions of Syrian Refugees by Lebanese Municipalities “Our Homes Are Not for Strangers” Mass Evictions of Syrian Refugees by Lebanese Municipalities Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35966 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-35966 “Our Homes Are Not for Strangers” Mass Evictions of Syrian Refugees by Lebanese Municipalities Summary ............................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 7 Methodology .................................................................................................................... -

200831 Baseline Report.Pdf

Agulhas Applied Knowledge Impact Analysis of Projects Implemented by LHSP through a Perception Study Baseline Report 31 July 2020 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 2. Introduction and methodology .......................................................................................... 4 Research background ............................................................................................................. 4 Communities .......................................................................................................................... 5 Survey structure and ToR alignment ..................................................................................... 6 Research approach ................................................................................................................ 7 Sampling ................................................................................................................................. 7 Limitations ............................................................................................................................. 9 Understanding survey data .................................................................................................. 10 Respondent profile .............................................................................................................. 10 3. Context and Outlook .......................................................................................................