Early Astronomy in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESALE Numberor Stating You Are a Retailor In

TucsonAuction08.html 9th Annual Tucson Meteorite Auction ----------------------------- Tucson Meteorite Auction 2008 Saturday, February 9th, 2008 Bidding starts 7:30PM Sharp Viewing & Socializing begins 5:30PM Food and Drink available http://www.michaelbloodmeteorites.com/TucsonAuction08.html (1 z 36) [2008-05-28 18:09:44] TucsonAuction08.html (Please drink only with a designated driver) ----------------------- While in Tucson I will have a cell phone: (619) 204-4138 (Feb2-Feb10) NEW LOCATION VFW Hall (Post # 549) 1884 So. Craycroft, Tucson, AZ 85711 (see directions below) NOTE: Click HERE for printer friendly copy of this catalog (Click on any photo to see a greatly enlarged image) 1 AH 1 Claxton L6, GeorgiaDecember 10 th , 1984 - Hit A Mailbox! .992g Rim Crusted Part Slice (21mm X 20mm X 2mm) No Minimum 2 AH 2 Dhofar 908 Lunar Meteorite - Rosetta - 1.242g Full Slice (24mm X 16mm X 2mm) No Minaimum - (est: $2.5K min) 3 AH 3 NWA 2999 Angrite Famous Paper "The Case For Samples From Mercury" 3.216g FC End Piece (18mm X 15mm X 7mm) No Minimum http://www.michaelbloodmeteorites.com/TucsonAuction08.html (2 z 36) [2008-05-28 18:09:44] TucsonAuction08.html 4 AH 4 NWA 4473 Polymict Diogenite 13g Full Slice(70mm X 13mm X ~2.5mm) No Minimum 5 AH 5 NWA 4880 (Shergottite) .540g 70% F Crusted Whole Stone (11mm X 9mm X 5mm) No Minimum 6 AH 6 NWA 4880 (Shergottite) 32.3g 92% FC Oriented Main Mass (35mm X 32mm X 32mm) Minimum Bid: $12,900.00 (Less Than $400/g) 7 AH 7 Oued el Hadjar (LL6) Fall March 1986 - "The Wedding Stone" 6.322 g (41mm X 30m X 3mm) The stone was broken into many pieces, then sacrificed on an alter during a wedding ceremony. -

Zinc and Copper Isotopic Fractionation During Planetary Differentiation Heng Chen Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2014 Zinc and Copper Isotopic Fractionation during Planetary Differentiation Heng Chen Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Heng, "Zinc and Copper Isotopic Fractionation during Planetary Differentiation" (2014). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 360. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/360 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Dissertation Examination Committee: Bradley L. Jolliff, Chair Jeffrey G. Catalano Bruce Fegley, Jr. Michael J. Krawczynski Frédéric Moynier Zinc and Copper Isotopic Fractionation during Planetary Differentiation by Heng Chen A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright © 2014, Heng Chen All rights reserved. Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES -

Capital Expenditures Report FY 2016 to FY 2020

Strategic Planning and Funding Capital Expenditures Report FY 2016 to FY 2020 October 2015 Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Vacant, CHAIR Robert “Bobby” Jenkins Jr., VICE CHAIR Austin David D. Teuscher, MD, SECRETARY TO THE BOARD Beaumont Dora G. Alcalá Del Rio S. Javaid Anwar Pakistan Christina Delgado, STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE Lubbock Ambassador Sada Cumber Sugarland Fred Farias III, OD McAllen Janelle Shepard Weatherford John T. Steen Jr. San Antonio Raymund A. Paredes, COMMISSIONER OF HIGHER EDUCATION Agency Mission The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board promotes access, affordability, quality, success, and cost efficiency in the state’s institutions of higher education, through Closing the Gaps and its successor plan, resulting in a globally competent workforce that positions Texas as an international leader in an increasingly complex world economy. Agency Vision The THECB will be recognized as an international leader in developing and implementing innovative higher education policy to accomplish our mission. Agency Philosophy The THECB will promote access to and success in quality higher education across the state with the conviction that access and success without quality is mediocrity and that quality without access and success is unacceptable. The Coordinating Board’s core values are: Accountability: We hold ourselves responsible for our actions and welcome every opportunity to educate stakeholders about our policies, decisions, and aspirations. Efficiency: We accomplish our work using resources in the most effective manner. Collaboration: We develop partnerships that result in student success and a highly qualified, globally competent workforce. Excellence: We strive for preeminence in all our endeavors. The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. -

June 17, 1983

mm S THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Meetin~ No. 793 May 11, 1983 Austin, Texas and Meeting No. 794 June 16-17, 1983 Dallas, Texas VOLUME XXX -E C O $ ili!i ~ i~ mm m am am mm ms ms mm mm am am am mm mm Meeting No. 794 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNI'gERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM i/ / Pages 1 - 100 June 16-17, 1983 Dallas, Texas R annam am m nn an n an nn Meeting No. 794 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages 1 - i00 June 16-17, 1983 Dallas, Texas r I m m B mm i i E m I mm N TABLE OF CONTENTS THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM JUNE 16-17, 1983 DALLAS, TEXAS MEETING NO. 794 JUNE 16, 1983 I. Attendance II. Recess for Committee Meetings JUNE 17, 1983 I. Welcome and Report by Charles C. Sprague, M.D., President of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Dallas 2 II. U.T. Board of Regents: Approval of Minutes of Regular Meeting on April 14-15, and Special Meeting on May ii, 1983 2 2 III. Introduction of Faculty and Student Representatives 5 IV. REPORTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF STANDING COMMITTEES A. REPORT OF EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 5 PERMANENT UNIVERSITY FUND . Authorization to Employ the Firm of A. G. Becker, Inc., Houston, Texas, to Perform an Audit of Investment Performance and Appropriation Therefor (Exec. -

Dark Skies Initiative

Dark Skies Initiative McDonald Observatory FORT DAVIS, TEXAS Star trails over the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Photo: Ethan Tweedie LIGHT POLLUTION IS INCREASING IN THE HEART OF THE DAVIS MOUNTAINS OF Apache Corporation tank battery using the latest dark sky friendly LED lighting technology. Note the light sources WEST TEXAS. Located atop Mount themselves are shielded from view, reducing glare, while providing a well lit working area. No light shines directly into the sky. Locke and Mount Fowlkes and under some Photo: Bill Wren/McDonald Observatory of the darkest night skies in the continental In recent years, the increase of oil and Permian Basin Petroleum Association and United States, sits the 500-acre world gas activity in the Permian Basin has the Texas Oil & Gas Association to publish renowned University of Texas at Austin’s resulted in an increase of light pollution a “Recommended Lighting Practices” McDonald Observatory. The Observatory’s that threatens the dark skies. To measure guide and accompanying training video mission is to inform, educate, and inspire the increase in light pollution surrounding in partnership with Apache Corporation, through their public programs, and support the Observatory, all sky photometry data that oil and gas operators in the Permian the teaching of the science and hobby of is collected to determine the rate at which can utilize to properly implement dark skies astronomy. The second largest employer the night skies are brightening. To address friendly lighting practices. in Jeff Davis County, the Observatory light pollution coming from the Permian, hosts approximately 100,000 visitors each the Observatory has partnered with the Dark skies friendly lighting has been found year. -

1962-11 Millman

MINUTES SPECIAL COUNCIL MEETING OF THE METEORITICAL SOCIETY held at Los Angeles, Calif., Sat., 17 Nov. 1962 PRESENT: President Peter M. Millman, Past-President John A. Russell, Editor Dorrit Hoffleit, Councilor C. H. Cleminshaw, and Secretary Gerald L. Rowland. Since Peter Millman and Dorrit Hoffleit were both in Los Angeles at the same time, and since it was possible to get a quorum of the Council together, President Millman called a Special meeting of the Council for Sat., 17 Nov. 1962. The last Council minutes (of 4 Sept., 1962) were read in order that those present might know the business that was transacted at Socorro, New Mexico. After some discussion, it was moved, seconded, and approved that arrangements be made for the transfer of a suitable number (approximately 40) of the 4 issues of Vol. I of Meteoritics from Springer Transfer Co. in Albuquerque, N. M., to John Russell at U.S.C. The Council approved the expenditure of whatever funds are necessary for this operation. John Russell reported that the Leonard Memorial Medal, which was displayed at the Socorro meeting, was unsatisfactory and that it is being re-done by the Southern California Trophy Co. The Council was reminded that the fund established for the Leonard Memorial Medal is still open for contributions. The cost of engraving and striking each individual medal to be presented will call for a nominal expenditure from time to time. The Council next suggested the following chairmen (subject to the individual's acceptance) for the standing committees of the Society: Eugene Shoemaker (Membership and Fellowship); Oscar Monnig (Finance and Endowment); Editor Dorrit Hoffleit (Publications). -

Reciprocal Museum List

RECIPROCAL MUSEUM LIST DIA members at the Affiliate level and above receive reciprocal member benefits at more than 1,000 museums and cultural institutions in the U.S. and throughout North America, including free admission and member discounts. This list includes organizations affiliated with NARM (North American Reciprocal Museum) and ROAM (Reciprocal Organization of American Museums). Please note, some museums may restrict benefits. Please contact the institution for more information prior to your visit to avoid any confusion. UPDATED: 10/28/2020 DIA Reciprocal Museums updated 10/28/2020 State City Museum AK Anchorage Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center AK Haines Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center AK Homer Pratt Museum AK Kodiak Kodiak Historical Society & Baranov Museum AK Palmer Palmer Museum of History and Art AK Valdez Valdez Museum & Historical Archive AL Auburn Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art AL Birmingham Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA), UAB AL Birmingham Birmingham Civil Rights Institute AL Birmingham Birmingham Museum of Art AL Birmingham Vulcan Park and Museum AL Decatur Carnegie Visual Arts Center AL Huntsville The Huntsville Museum of Art AL Mobile Alabama Contemporary Art Center AL Mobile Mobile Museum of Art AL Montgomery Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts AL Northport Kentuck Museum AL Talladega Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center AR Bentonville Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art AR El Dorado South Arkansas Arts Center AR Fort Smith Fort Smith Regional Art Museum AR Little Rock -

Candace Leah Gray EDUCATION EMPLOYMENT

Candace Leah Gray 1258 Oneida Drive Las Cruces, NM 88005 915-861-4407 candaceg@nmsu edu EDUCATION New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM !" D in #s$ronom& 2010 – 2015 (hesis (i$)e* The Effect of Solar Flares, Coronal Mass Ejections, and Co-rotating Interaction Regions on Venus's 5577 ! "#$gen %reen &ine (hesis advisor* Dr Nancy Chanover University of Texas at Austin, #us$in, (+ ,(each pr%gram .or $eaching cer$i/ca$ion 2009 – 2010 M # in #s$ronom& 2006 – 2009 (hesis (i$)e* ' Chemical Sur)ey of 67 Comets Conducted at McDonald ",ser)ator$ (hesis advisor* Drs #ni$a Cochran and 0d1ard 2obinson University of Texas at E !aso, 0) !as%, (+ 4 5 in !"&sics 1i$h minor s$udies in Ma$hema$ics 2001 – 2006 (hesis (i$)e* Radio ",ser)ations of Magnetic Catacl$s(ic Variable Stars at the Very &arge 'rray (hesis advisor* Dr !au) Mason EM!LO"MENT A#ache !oint O$servatory% 5uns-%$, NM 2015 – !resen$ 5uppor$ #s$ronomer New Mexico State University% Las Cruces, NM 2esearch assis$ant in #s$ronom& 2010 – 2015 (eaching assis$ant in #s$ronom& 2010 – 2011 Austin Com&unity Col e'e, #us$in, (+ 6ns$ruc$or %. !"&sics and #s$ronomy 5ummer 2010 7untington (igh School, #us$in, (+ 6ns$ruc$or %. !"&sics 5pring 2010 CV Candace Gray 2 /7 University of Texas at Austin, #us$in, (+ !ain$er 7a)) (e)escope Opera$%r 2009 – 2010 2esearch assis$ant in #s$ronom& 2007 – 2009 (eaching assis$ant in #s$ronom& 2006 – 2007 University of Texas at E !aso, 0) !as%, (+ 2esearch assis$ant in #s$ronom& 2003 – 2005 (eaching assis$ant in !"&sics 5pring 2006 (eaching assis$ant in #s$ronom& 9a)) 2003 )ESEA)C( E*!ERIENCE :"i)e m& researc" remains )arge)& in $he /e)d %. -

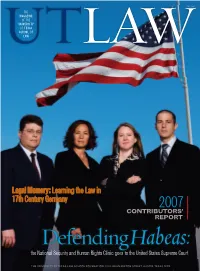

Fall 2007 Issue of UT Law Magazine

FALL 2007 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF UTLAW LAW 2007 CONTRIBUTORS’ REPORT Defending Habeas: the Nationalational Security and Human Rights CCliniclinic ggoesoes ttoo tthehe United States SuSupremepreme CCourtourt THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS LAW SCHOOL FOUNDATION, 727 E. DEAN KEETON STREET, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 UTLawCover1_FIN.indd 2 11/14/07 8:07:37 PM 22 UTLAW Fall 2007 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 22 11/14/07 7:46:29 PM InCamera Immigration Clinic works for families detained in Taylor, Texas The T. Don Hutto Family Residential Facility in Taylor, Texas currently detains more than one hundred immigrant families at the behest of the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. The facility, a former medium security prison, is the subject of considerable controversy regarding the way detainees are treated. For the past year, UT Law’s Immigration Clinic has worked to improve the conditions at Hutto. In this photograph, (left to right) Farheen Jan,’08, Elise Harriger,’08, Immigration Clinic Director and Clinical Professor Barbara Hines, Matt Pizzo,’08, Clinic Administrator Eduardo A Maraboto, and Kate Lincoln-Goldfi nch, ’08, stand outside the Hutto facility. Full story on page 16. Photo: Christina S. Murrey FallFall 2007 2007 UT UTLAWLAW 23 1 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 23 11/14/07 7:46:50 PM 6 16 10 4 Home to Texas 10 Legal Memory: 16 Litigation, Activism, In the Class of 2010—students who Learning the Law in and Advocacy: entered the Law School in fall 2007— thirty-eight percent are Texas residents 17th-Century Germany Immigration Clinic works who left the state for their undergradu- ate educations and then returned for One of the remarkable books in the for detained families law school. -

Keaton J. Bell Curriculum Vitae

Keaton J. Bell Curriculum Vitae E-mail: [email protected] Web: faculty.washington.edu/keatonb Citizenship: United States Research Interests Time domain astronomy; stellar astrophysics; exoplanets; asteroseismology; white dwarf stars Postdoctoral Research Positions University of Washington, Seattle, WA September 2019{present NSF Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow Data Intensive Research in Astrophysics and Cosmology (DIRAC) Fellow Max Planck Institute of Solar System Research, G¨ottingen,Germany August 2017{August 2019 Stellar Ages and Galactic Evolution (SAGE) Group (PI: Saskia Hekker) Education University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas July 2017 Ph.D., Astronomy Thesis Title: \Pulsational Oddities at the Extremes of the DA White Dwarf Instability Strip" Supervisors: D. E. Winget and M. H. Montgomery University of Washington, Seattle, Washington December 2010 B.S., Astronomy (with honors), Physics Research Adviser: Suzanne L. Hawley Awards and Honors NSF Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellowship, $300,000 September 2019 Chambliss Astronomy Achievement Student Award, 230th AAS Meeting June 2017 Publication Summary Refereed Publications: 48 total; 8 first-author; h-index: 19 Observing Summary ARC 3.5m Telescope, Apache Point Observatory 2020{present Confirming Candidate Planet Transits of White Dwarfs from ZTF, 24 nights (PI) 2.1m Otto Struve Telescope, McDonald Observatory 2013{2017 Time Series Photometry of Variable White Dwarfs, 256 nights (PI) Recent Conferences and Workshops Zwicky Transient Facility Summer School -

The Oscar E. Monnig Meteorite Collection and Museum. Rg

41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2010) 1162.pdf THE OSCAR E. MONNIG METEORITE COLLECTION AND MUSEUM. R. G. Mayne1 and T. Moss1 De- partment of Geology, TCU Box 298830, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX 76109 ([email protected]) The Man Behind the Meteorites [1]: Oscar not knowing the full extent of what was to come. In Monnig was born in Fort Worth, Texas in 1902, and he the years that followed a number of meteorites were lived there till his death in 1999. He was a business- transferred to TCU, but it was not until his death in man and he started work for his family’s dry goods 1999 that the full generosity of Oscar’s offer came to company after earning his law degree from the Univer- light. TCU not only inherited all of Oscar’s meteorite sity of Texas in 1925 and was the CEO of the company collection, but also a large amount of his estate for when it was sold in 1982. However, Oscar’s passion “education, care, and maintenance of the meteorite was for meteorites, he was an avid collector. He even collection.” gave self-printed brochures to his traveling salesmen to The Monnig Meteorite Collection at TCU: The distribute that described how to identify meteorites and collection donated by Oscar Monnig was one of the offered to purchase any that were found. finest private collections of its day, and it is now one In 1960 Oscar Monnig introduced himself to a new of the finest University-based collections in the world, hire in the TCU Geology department, Dr. -

Moon Glides by Bright Star, Mars Next Week Before Dawn 22 July 2011

Moon glides by bright star, Mars next week before dawn 22 July 2011 winter sky. Mars doesn't generate any light on its own. Instead, like the Moon, it shines by reflecting sunlight. The light strikes a surface that is painted in varying shades of orange, yellow, gray, and black. Most of the orange and yellow are produced by fine-grained dust that contains a lot of iron oxide, better known as rust. As Mars grows brighter later in the year, its color will appear to grow more intense. By year's end, you'll see why it is called the Red Planet, as Mars provides one of the most vivid spots of color in the night sky. Published bi-monthly by The University of Texas at (PhysOrg.com) -- The Moon puts on a great show Austin McDonald Observatory, StarDate magazine before dawn next week as it passes by a bright provides readers with skywatching tips, skymaps, star and planet, according to the editors of beautiful astronomical photos, astronomy news and StarDate magazine. features, and a 32-page Sky Almanac each January. The Moon stands closest to Aldebaran, the bright star known as the eye of Taurus, the bull, an hour before dawn on Tuesday the 26th in the eastern Provided by University of Texas McDonald sky. The Moon shines next to Mars in the east at Observatory the same time the following morning. Both Mars and Aldebaran glow orange, but right now Aldebaran is about twice as bright as Mars. Color is a rare commodity in the night sky.