Banking Guidelines Review Public Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD FINTECH REPORT 2018 Contents 4 Preface

in collaboration with WORLD FINTECH REPORT 2018 Contents 4 Preface 8 Executive Summary FinTechs Are Redefining the Financial Services Customer Journey 13 Competition and Rising Expectations Spur 14 Customer-Centricity Push – Identify gaps left by traditional Financial Services providers and explore changing customer expectations. Emerging Technologies Enable Customer 19 Journey Transformation – Data and insights are reshaping personalized experiences through automation and distributed ledger technology. Alignment with Customer Goals, Creation of 27 Trust, and Delivery of Digital, Agile, and Efficient Processes Are Catalysts for Success – Firms are driving innovation and operational excellence through agile and digital teams. World FinTech Report 2018 The Symbiotic Relationship between FinTechs and Traditional Financial Institutions 35 FinTech and Incumbent Firms’ Respective 36 Competitive Advantages and Shortcomings Make Collaboration a Logical Fit – A partnership ecosystem of FinTechs, incumbents, and other vendors fosters a win-win for stakeholders. Finding the Right Partners for Collaboration 44 Is Essential – Maintaining and accelerating scale is a common FinTech firm struggle, so the right collaboration partner is critical. Successful Collaboration Requires Commitment 49 and Agility from FinTechs and Incumbents – Selection of the appropriate engagement model boosts FinTech scale-up efforts. The Path Forward: An Impending Role for BigTechs? 60 – BigTechs could have massive impact on the Financial Services industry. Preface Once rather homogenous and somewhat staid, the financial services marketplace has transformed into a dynamic milieu of bar-raising specialists. These new-age professionals are devoted to meeting and exceeding the expectations of consumers who have become accustomed to personalized services from industries such as retail, travel, and electronics. Financial services customers no longer rely on one or two firms. -

FINTECH – BANK MODEL a Baseline Review of Best PARTNERSHIPS Practices and Pitfalls…

FINTECH – BANK MODEL A baseline review of best PARTNERSHIPS practices and pitfalls…. Comments by Comptroller Otting before the House Financial Services Committee in June 2018: BANK— “The world has changed dramatically over the last two years.” FINTECH “Fintechs used to think that they wanted to be banks; and, now, most are realizing because of the capital, liquidity, and commitment to the community they have to PARTNERSHIPS provide, they really don’t want to be.” “More and more Fintechs are talking to us about how they partner with banks to be able to provide portals and things where they can reach customers.” SHIFTING TO DIGITAL SOLUTIONS • Digital/Mobile Banking • Marketplace Lending • Payments • Deposit Gathering • Banking as a Platform • Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning • “RegTech” THE SHIFT IN BANKING TECHNOLOGY “Mobile first, digital everything.” Jamie Dimon, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. on the bank’s new mantra guiding its future growth. Mobile Banking App Usage Post- THE MIGRATION TO Covid ONLINE/DIGITAL BANKING The Big 6 banks (Bank of America, Chase, Citibank, PNC, U.S. Bank and 20% Wells Fargo) currently have a jump No Change on regional and midsize banks to 42% Use It Less build digital engagement. I Don't Use It Used for First Time Use It A Lot More 24% Use It A Little More Prior to the pandemic, 49% of big bank customers had high levels of 6% 5% 3% digital engagement, compared with 41% of regional bank customers and 36% of midsize bank customers. *Source: J.D. Power (Sept. 2020) DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION SPANS GENERATIONS AND CHANNELS CURRENTLY USE DIGITAL BANKING 85% PERSONALLY COMMERCIAL CUSTOMERS THAT 95% WANT DIGITAL BANKING 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Source: ABA (Feb. -

On the Securitization of Student Loans and the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009

On the Securitization of Student Loans and the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 by Maxime Roy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Tepper School of Business Carnegie Mellon University May 16, 2017 Committee: Burton Hollifield (chair), Adam Ashcraft, Laurence Ales and Brent Glover External Reader: Pierre Liang À Françoise et Yvette, mes deux anges gardiens. abstract This dissertation contains three chapters, and each examines the securitization of student loans. The first two chapters focus on the underpricing of Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) collateralized by government guaranteed student loans during the financial crisis of 2007–2009. The findings add to the literature that documents persistent arbitrages during the crisis and doing so in the ABS market is a novelty. The last chapter focuses on the securitization of private student loans, which do not benefit from government guarantees. This chapter concentrates on whether the disclosure to investors is sufficient to prevent the selection of underperforming pools of loans. My findings have normative implications for topics ranging from the regulation of securitization to central banks’ exceptional provision of liquidity during crises. Specifically, in the first chapter, “Near-Arbitrage among Securities Backed by Government Guaranteed Student Loans,” I document the presence of near-arbitrage opportunities in the student loan ABS (SLABS) market during the financial crisis of 2007–2009. I construct near-arbitrage lower bounds on the price of SLABS collateralized by government guaranteed loans. When the price of a SLABS is below its near-arbitrage lower bound, an arbitrageur that buys the SLABS, holds it to maturity and finances the purchase by frictionlessly shorting short-term Treasuries is nearly certain to make a profit. -

Sofi: We Help You Get Your Money Right

Get Your Money Right Borrow, Save, Spend, Invest and Protect © 2020 Social Finance, Inc. Confidential Information. Do not copy or distribute. Advisory services offered through SoFi Wealth LLC. SoFi Money® is offered through SoFi Securities LLC. SoFi Lending Corp., CFL #6054612. NMLS #1121636. Disclaimer Confidentiality and Disclosures This presentation has been prepared for use by Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings Corp. V (“Social Capital”) and Social Finance, Inc. (“SoFi”) in connection with their proposed business combination. This presentation is for information purposes only and is being provided to you solely in your capacity as a potential investor in considering an investment in Social Capital and may not be reproduced or redistributed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Social Capital and SoFi. Neither Social Capital nor SoFi makes any representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this presentation. The information in this presentation and any oral statements made in connection with this presentation is subject to change and is not intended to be all-inclusive or to contain all the information that a person may desire in considering an investment in Social Capital and is not intended to form the basis of any investments decision in Social Capital. This presentation does not constitute either advise or a recommendation regarding any securities. You should consult your own legal, regulatory, tax, business, financial and accounting advisors to the extent you deem necessary, and must make your own decisions and perform your own independent investment and analysis of an investment in Social Capital and the transactions contemplated in this presentation. -

Numerical.Pdf

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Numerical Sort ) Month Ending - July 31, 2021 NUMBER PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME 0 SERIES 0005 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO. LLC 0010 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO. 0013 SANFORD C. BERNSTEIN & CO., LLC 0015 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC 0017 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC 0019 JEFFERIES LLC 0031 NATIXIS SECURITIES AMERICAS LLC 0032 DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC.- STOCK LOAN 0033 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC/FIXED INC. REPO & COMM. PAPER 0045 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. 0046 PHILLIP CAPITAL INC./STOCK LOAN 0050 MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC 0052 AXOS CLEARING LLC 0057 EDWARD D. JONES & CO. 0062 VANGUARD MARKETING CORPORATION 0063 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU FINANCIAL BD LLC 0065 ZIONS DIRECT, INC. 0067 INSTINET, LLC 0075 LPL FINANCIAL LLC 0076 MUFG SECURITIES AMERICAS INC. 0083 TRADEBOT SYSTEMS, INC. 0096 SCOTIA CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0099 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU ITG LLC 100 SERIES 0100 COWEN AND COMPANY LLC 0101 MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC/SL CONDUIT 0103 WEDBUSH SECURITIES INC. 0109 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO./ETF 0114 MACQUARIE CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0124 INGALLS & SNYDER, LLC 0126 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC 0135 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC/INVESTMENT ACCOUNT 0136 INTESA SANPAOLO IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0141 WELLS FARGO CLEARING SERVICES, LLC 0148 ICAP CORPORATES LLC 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0161 BOFA SECURITIES, INC. 0163 NASDAQ BX, INC. 0164 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO., INC. 0166 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0180 NOMURA SECURITIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. 0181 GUGGENHEIM SECURITIES, LLC 0187 J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC 0188 TD AMERITRADE CLEARING, INC. 0189 STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS, LLC 0197 CANTOR FITZGERALD & CO. / CANTOR CLEARING SERVICES 200 SERIES 0202 FHN FINANCIAL SECURITIES CORP. 0221 UBS FINANCIAL SERVICES INC. -

Sofi Professional Loan Program 2020-C Trust

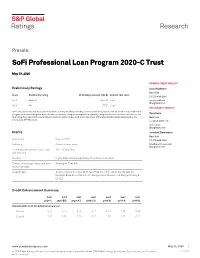

Presale: SoFi Professional Loan Program 2020-C Trust May 13, 2020 PRIMARY CREDIT ANALYST Preliminary Ratings Lyuda Ryabkova New York Class Preliminary rating Preliminary amount (mil. $) Interest rate (%)(i) (1) 212-438-2897 A-FX AAA (sf) 455.00 Fixed lyuda.ryabkova @spglobal.com B-FX NR 27.50 Fixed SECONDARY CONTACTS Note: This presale report is based on information as of May 13, 2020. The rating shown is preliminary. Subsequent information may result in the assignment of a final rating that differs from the preliminary rating. Accordingly, the preliminary rating should not be construed as evidence of a Piper Davis final rating. This report does not constitute a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell securities. (i)The interest rates will be determined on the New York pricing date. NR--Not rated. + 1 (212) 438 1173 piper.davis @spglobal.com Profile Jonathan Zimmerman New York Closing date May 19, 2020. (1) 212-438-1002 Collateral Private student loans. jonathan.zimmerman @spglobal.com Loan originator, sponsor, seller, and SoFi Lending Corp. administrator Servicer Higher Education Loan Authority of the State of Missouri. Trustee, underlying trustee, and bank Wilmington Trust N.A. account provider Underwriters Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC, BofA Securities Inc., Citigroup Global Markets Inc., Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., J.P. Morgan Securities LLC, and Morgan Stanley & Co. LLC. Credit Enhancement Summary SoFi SoFi SoFi SoFi SoFi SoFi SoFi 2020-C 2020-B(i) 2020-A(i) 2019-C(i) 2019-B 2019-A 2018-D Subordination (% of the initial bond balance) Class A 5.70 5.70 5.70 5.70 6.73 7.68 8.33 Class B 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 www.standardandpoors.com May 13, 2020 1 © S&P Global Ratings. -

PPP Perks ‘Workers’ Over Wall Street Sen

MONDAY JANUARY 11, 2021 VOL. 186 No. 6 AMERICANBANKER.COM Follow us on Twitter @AmerBanker Incoming Dem chair says 5 banking panel will put PPP perks ‘workers’ over Wall Street Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio signaled See story on page 2 a change in direction for the Banking Committee under Democratic control, on Lenders with less than $1B of assets get exclusive the same day he called for President Trump’s ouster after the U.S. Capitol riot. Page 5 portal access for first two days SoFi to go public via SBA plans to match some borrowers with small 6 SPAC with $8.7B valuation The deal between San Francisco-based lender lenders and Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings Corp. V is latest example of a closely held firm going public by merging with a special SBA portal will have dedicated hours for smallest purpose acquisition company. Page 6 PPP lenders Amex said to face inquiry 7 into business credit Lender fees increased for loans of $50,000 or less card sales tactics American Express is reportedly under investigation by a top federal agency $15B in funds set aside for lenders with $1B or less of exploring allegations of unethical sales assets tactics by the company’s small-business credit card sales representatives. Page 6 Source: SBA PayPal blocks group 8 that helped Trump supporters travel to D.C. dailybriefing Inside Amex’s data-driven PayPal Holdings closed an account held by 3 effort to personalize Joy In Liberty, one of the groups that paid for customer service supporters of President Donald Trump to More incentives for smaller American Express has spent years refining travel to Washington, where mobs stormed 1 lenders in next PPP round a decision-making engine that can tailor the U.S. -

Sofi Announces Agreement to Acquire Golden Pacific Bancorp, Inc

SoFi Announces Agreement to Acquire Golden Pacific Bancorp, Inc. Acquisition Marks Significant Step in SoFi’s Effort to Obtain National Bank Charter SAN FRANCISCO -- Tuesday, March 9, 2021 -- Social Finance, Inc. (“SoFi”), the digital personal finance company, today announced that it has signed a definitive agreement to acquire Golden Pacific Bancorp, Inc. (OTCPK: GPBI) and its wholly owned subsidiary Golden Pacific Bank, N.A. (together, “GPB”). GPB is a Sacramento, California-based community bank that is regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and has approximately $150 million in assets. SoFi will pay $2.55 in cash for each share of GPB or approximately $22.3 million in aggregate to acquire GPB to advance SoFi’s effort to obtain a national bank charter. The proposed acquisition is a key strategic step in SoFi's path to obtaining a national bank charter. As a result of the proposed acquisition, SoFi will switch its current de novo bank application to a change of control application. If successfully granted a national bank charter by the OCC and Federal Reserve pursuant to its change of control application, SoFi plans to contribute $750 million in capital and pursue its national, digital business plan while maintaining GPB’s community bank business and footprint, including GPB’s current three physical branches. Once the transaction is complete-- which is anticipated before the end of 2021--GPB’s community bank business will operate as a division of SoFi Bank, N.A., a renaming of GPB's bank entity. GPB President and Chief Executive Officer Virginia Varela will continue to lead the GPB community bank business under the direction of Paul Mayer, who will serve as President of SoFi Bank, N.A. -

Consumers Beware: How Are Your Favorite “Free” Investment Apps Regulated?

CONSUMERS BEWARE: HOW ARE YOUR FAVORITE “FREE” INVESTMENT APPS REGULATED? SIQI WANG†1 ABSTRACT The proliferation of free or low-cost investment apps has disrupted the financial industry in recent years. Major brokerage firms have been pressured to go to zero fees due to intense competition from their fintech counterparts. While these apps have extended their products and services to those underserved by traditional brokers, some of their practices raise consumer protection concerns. Namely, the practice of “payment for order flow,” which helps fintech startups sustain a zero-commission model, could lead to subordinating customers’ best interest to market makers who acquire their retail orders from these fintech startups. Further, “cash management accounts,” newly popular among fintech startups with an ambition to compete with chartered banks raise questions about the use of idle customer assets and the protections afforded to these accounts in case of liquidation. This Note considers the products and services of these investment apps in the context of existing U.S. regulations and regulators for broker-dealers, investment advisors, and chartered banks. To illustrate this, this Note analyzes the potential consumer financial protection issues arising out of these fintech-based investment platforms’ distinctive business models and the services they provide. INTRODUCTION Robinhood, Acorns, Betterment, Stash, and other free or low-cost investment apps make it easier than ever for every smartphone user to invest on the go, with zero experience and little more than pocket change. These kinds of apps are exploding right now, appealing mainly to young people because of their “low barriers to entry, automation and familiar tap- swipe-buy, Tinder-style interface.”2 For almost all of these apps, all users have to do is first download the app, then set up a profile that lets the company behind the app know the best kinds of investment suitable for the user’s risk averseness and return expectations, and finally connect a bank account to give access to some funds and be done. -

Apex Clearing Corporation (APXF) Event: Moffettnathanson's 3Rd

Company Name: Apex Clearing Corporation (APXF) Event: MoffettNathanson’s 3rd Annual Payments, Processors, and IT Services Summit Date: May 10, 2021 Lisa Ellis, Analyst, MoffettNathanson LLC All right, terrific. Well, that was a quick switch over, time to move now to the bottom of the hour 11:30 session. This is a fireside chat now with one of my personal favorite, most exciting, new up and coming FinTech companies, actually the FinTech for FinTechs, as they will tell you, Bill Capuzzi, CEO; and Chris Springer, CFO of Apex Clearing are joining us. So first, I’ll just say, Bill, and Chris thank you. Thanks for being here. Bill Capuzzi, Chief Executive Officer Thanks for having us. Christopher Springer, Chief Financial Officer Thanks for having us. Lisa Ellis, Analyst, MoffettNathanson LLC Of course. And we’re going to start off actually, Bill and Chris are going to present for the first 15 minutes or so of this. Some slides to give a quick overview of Apex realizing many folks joining may be unfamiliar with the company, a picture’s worth 1000 words. So, they’re going to go through a few slides. In the meantime, guys, as usual, you can submit questions to me directly through the webcast. I’ve got them up in front of me. So, as questions come up, as you’re listening to their presentation, please do send them through. We’re going to have 10 minutes or so at the end to do some Q&A. Okay. And with that, I’ll turn it over to Bill and Chris. -

January 2021 Short Squeeze Trading Litigation ______

Case 1:21-md-02989-CMA Document 358 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/27/2021 Page 1 of 136 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. 21-2989-MDL-ALTONAGA/Torres IN RE: JANUARY 2021 SHORT SQUEEZE TRADING LITIGATION ____________________________________/ This Document Relates to: ALL ANTITRUST ACTIONS CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT [REDACTED VERSION] i Case 1:21-md-02989-CMA Document 358 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/27/2021 Page 2 of 136 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... JURISDICTION AND VENUE ...................................................................................................... PARTIES ......................................................................................................................................... A. Plaintiff Angel Guzman ...................................................................................................... B. Plaintiff Burke Minahan ...................................................................................................... C. Plaintiff Christopher Miller ................................................................................................. D. Plaintiff Terell Sterling ........................................................................................................ E. Introducing Brokerage Defendants ..................................................................................... F. Self-Clearing -

Sofi Wealth LLC

SoFi Wealth LLC Item 1: ADV Part 2A Cover Page 234 1st St. San Francisco, CA 94105 (855) 525-7634 www.sofi.com September 13, 2021 This brochure provides information about the qualifications and business practices of SoFi Wealth, LLC (“SoFi Wealth” or the “Firm”). If you have any questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at (855) 525-7634. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) or by any state securities authority. SoFi Wealth is registered with the SEC as an investment adviser; please note that such registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Additional information about SoFi Wealth also is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.go Item 2: Material Changes Under SEC Rules, you will receive a summary of any material changes to this and subsequent Brochures within 120 days of the close of our fiscal year, which is in December. We may also provide you with a new Brochure or other ongoing disclosure information about material changes as necessary, without charge. Since filing the last Amendment to this Brochure in June 2021, we have made the following material changes: ● On April 12, 2021, SoFi Wealth LLC settled, without admitting or denying the allegations, a matter brought by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Pursuant to the terms of the settlement, a final order was issued on August 19, 2021. Details are provided in Item 9: Disciplinary Information. Item 3: Table of Contents Item