Old Testament Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Medieval-Magazine-No11

MEDIEVAL STUDIES MAGAZINE FROM MEDIEVALISTS.NET The Medievalverse Number 11 April 13, 2015 Five Great Ladies Who Refused to Be Quiet A Broken Book of Hours Beef and Pork in the Middle Images of Women Reading Ages in the Middle Ages 8 16 32 How to recreate a Viking funeral – minus the human sacrifice | Monty Python and the Holy Grail The Medievalverse April 13, 2015 Page 6 Medieval Medicine and Modern Science: An Interview with Freya Harrison Last week’s news that researchers have discovered that an Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infections has performed well in tests against the MRSA bacteria has drawn media attention from around the world Page 11 Medieval MOOCs Interested in learning about medieval history? Here are four free online courses you can take within the next few months. Page 20 10 Must See Italian Works of Art at the National Galley What to look for when inside the National Gallery in London. Page 38 Dragon's Blood & Willow Bark: The Mysteries of Medieval Medicine Read an excerpt from Toni Mount's new book and find out how our readers can get 20% off when they order it. Table of Contents 4 Joan of Arc Museum opens in France 5 New spectrometer may revolutionize archaeology 6 Medieval Medicine and Modern Science: An Interview with Freya Harrison 8 A Broken Book of Hours – Saving a Medieval Manuscript 11 Medieval MOOCs 13 Monty Python and the Holy Grail Turns 40 14 Five Great Ladies Who Refused to Be Quiet 16 Beef and Pork in the Middle Ages 19 Medieval Articles 20 10 Must See Italian Works of Art at the National Galley 26 How to recreate a Viking funeral – minus the human sacrifice 29 Ten Thoughts on Game of Thrones: The Wars to Come 32 Images of Women Reading in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 38 Dragon's Blood & Willow Bark: The Mysteries of Medieval Medicine 40 Medieval Videos THE MEDIEVALVERSE Edited by: Peter Konieczny and Sandra Alvarez Website: www.medievalists.net This digital magazine is published each Monday. -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Chicago Poems by Carl Sandburg)

CHICAGO POEMS By Carl Sandburg Originally published by Henry Holt and Company, New York This digital reprint published by E S P Electronic Scholarly Publishing http://www.esp.org Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project Series Editor: Robert J. Robbins The Electronic Scholarly Publishing project has received support from the ELSI component of the United States Department of Energy Human Genome Project. ESP also welcomes help from volunteers and collaborators, who recommend works for publication, provide access to original materials, and assist with technical and production work. If you are interested in volunteering, or are otherwise interested in the project, contact the series editor: [email protected]. Bibliographical Note This ESP edition, first electronically published in 2003, is a newly typeset, unabridged version, based on the 1916 edition published by Henry Holt and Company. Production Credits Scanning of originals: ESP staff OCRing of originals: ESP staff Typesetting: ESP staff Proofreading/Copyediting: ESP staff Graphics work: ESP staff Copyfitting/Final production: ESP staff New material in this electronic edition is © 2003, Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for educational or scholarly purposes, provided that these copyright notices are included. The document may not be reprinted or redistributed, in any form (printed or electronic), for commercial purposes without written permission from the copyright holders. PREFATORY NOTE Some of these writings were first printed in Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, Chicago. Permission to reprint is by courtesy of that publication. The writer wishes to thank Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson, editors of Poetry, and William Marion Reedy, editor of Reedy’s Mirror, St. -

Game of Thrones (Music from the HBO® Series) Season 5

1 2 Music by Ramin Djawadi Music Produced by Ramin Djawadi Music Supervisor: Evyen J Klean Music Editor: David Klotz Orchestrator: Stephen Coleman Performed by: The Czech Film Orchestra and Choir Music Contractor: Zdena Pelikánová Copyist: Pavel Ciboch Recorded at CNSO Studios, Prague Technical Score Advisors: Brandon Campbell, William Marriott Mastered by: Gavin Lurssen at Lurssen Mastering Executive in Charge of WaterTower Music: Jason Linn Art Direction: Sandeep Sriram 3 4 5 6 Ramin would like to thank: David Benioff, D.B. Weiss, Carolyn Strauss, Greg Spence, George R.R. Martin, David Nutter, Mark Mylod, Jeremy Podeswa, Miguel Sapochnik, Michael Slovis, Holly Schiffer, Janet Graham-Borba, Onnalee Blank, Matt Waters, Spike Allison Hooper, Melissa Demino, Chris Zampas, Alan Frier, Maria Machado, Sam Schwartz, Michael Gorfaine, Cheryl Tiano, everybody at Remote Control, Sandrine Pecher, Uli Kurtinat, the Djawadi family, Hans Zimmer, Jennifer Hawks Thanks to: Stacey Abiraj, Peter Axelrad, Tara Bonner, Paul Broucek, Rocco Carrozza, Janis Fein, Joshua Goodstadt, Lauren Houston, Joe Kara, Kevin Kertes, Genevieve Morris, Jaimie Roberts, Rebel Roy Steiner, Jr., Robert Zick Score Written by: Ramin Djawadi Score Published by: T-L Music Publishing (ASCAP) 7 8 1. Main Titles 2. Blood Of The Dragon 3. House Of Black And White 4. Jaws Of The Viper 5. Hardhome Pt. 1 6. Hardhome Pt. 2 7. Mother’s Mercy 8. Kill The Boy 9. Dance Of Dragons 10. Kneel For No Man 11. High Sparrow 12. Before The Old Gods 13. Atonement 14. I Dreamt I Was Old 15. The Wars To Come 16. Forgive Me 17. Son Of The Harpy 18. -

Carolyne Larrington

Winter is coming Carolyne Larrington Winter is coming LES RACINES MÉDIÉVALES DE GAME OF THRONES Traduit de l’anglais par Antoine Bourguilleau ISBN 978‑2‑3793‑3049‑0 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : 2019, avril © Passés Composés / Humensis, 2019 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75014 Paris Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions stric‑ tement réservées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collec‑ tive » [article L. 122‑5] ; il autorise également les courtes citations effectuées dans un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » [article L. 122‑4]. La loi 95‑4 du 3 janvier 1994 a confié au C.F.C. (Centre français de l’exploitation du droit de copie, 20, rue des Grands Augustins, 75006 Paris), l’exclusivité de la gestion du droit de reprographie. Toute photocopie d’oeuvres protégées, exécutée sans son accord préalable, constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles 425 et suivants du Code pénal. Sommaire Liste des abréviations ....................................................... 9 Préface ................................................................................ 15 Introduction ....................................................................... 19 Chapitre 1. Le Centre ........................................................ 31 Chapitre 2. Le Nord ......................................................... -

Game of Thrones Season Five Trading Cards Checklist

Game of Thrones Season Five Trading Cards Checklist Base Cards Card Image Card Title # 001 The Wars to Come 002 The Wars to Come 003 The Wars to Come The House of Black and 004 White The House of Black and 005 White The House of Black and 006 White 007 High Sparrow 008 High Sparrow 009 High Sparrow 010 Sons of the Harpy 011 Sons of the Harpy 012 Sons of the Harpy 013 Kill The Boy 014 Kill The Boy 015 Kill The Boy Unbowed, Unbent, 016 Unbroken Unbowed, Unbent, 017 Unbroken Unbowed, Unbent, 018 Unbroken 019 The Gift 020 The Gift 021 The Gift 022 Hardhome 023 Hardhome 024 Hardhome 025 The Dance of Dragons 026 The Dance of Dragons 027 The Dance of Dragons 028 Mother's Mercy 029 Mother's Mercy 030 Mother's Mercy 031 Sansa Stark 032 Theon Greyjoy 033 Petyr "Littlefinger" Baelish 034 Tyrion Lannister 035 Samwell Tarly 036 Arya Stark 037 Bronn 038 Jon Snow 039 Brienne of Tarth 040 Ser Davos Seaworth 041 Daenerys Targaryen 042 Lord Varys 043 Ser Jaime Lannister 044 Grand Maester Pycelle 045 Stannis Baratheon 046 Queen Cersei Lannister 047 Margaery Tyrell 048 Ser Jorah Mormont 049 Dragons 050 Melisandre 051 Podrick Payne 052 Barriston Selmy 053 Roose Bolton 054 Tormund Giantsbane 055 Gilly 056 Mance Rayder 057 Ramsay Snow 058 Grey Worm 059 Lady Olenna Tyrell 060 Missandei 061 Ser Loras Tyrell 062 Meryn Trant 063 Ellaria Sand 064 Daario Naharis 065 Maester Aemon 066 Alliser Thorne 067 Qyburn 068 Janos Slynt 069 Olyver 070 Selyse Baratheon 071 Mace Tyrell 072 King Tommen Baratheon 073 Eddison Tollett 074 Olly 075 Shireen Baratheon 076 Hizdahr zo Loraq -

Master Dialogue for Game of Thrones Seasons 3 Through 8

GAME OF THRONES #302 MASTER DOCUMENT Language Translations David J. Peterson Revised 8/7/12 KEY: (Title of Associated .mp3 File) CHARACTER NAME English dialogue as written. TRANSLATION Official transcription for closed captioning and subtitles. PHONETIC fo-NE-tik REN-dur-ing Literal translation. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2.14 EXT. ASTAPOR - APPROACH TO PRESENTATION AREA - DAY 2.14 (s3e2sc2-14_1.mp3) KRAZNYS Tell the Westerosi whore that these Unsullied have been standing here a day and a night, with no food or water. TRANSLATION Ivetra ji live Vesterozia sko bezi Dovoghedhi kizir jortis me tovi si me banti, do havor dore jedhar dos. PHONETIC i-ve-TRA ji LI-ve ves-te-ro-ZI-a sko BE-zi do-vo-GHE-dhi KI-zir JOR- tis me TO-vi si me BAN-ti, do HA-vor DO-re JE-dhar dos. Tell the whore Westerosi that these Unsullied here have stood a day and a night, no food nor water with. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2.14AEXT. PRESENTATION AREA - CONTINUOUS 2.14A (s3e2sc2-14A_1.mp3) (CONTINUED) GAME OF THRONES Master Dialogues (Season 3-8) 04/11/20 2. 2.14ACONTINUED: 2.14A KRAZNYS Tell the silver-haired slut they will each stand until they drop. Such is their obedience. TRANSLATION Ivetra ji rene eji oghrar gelinko sko majorozlivis eva ruhilis (ERROR: Should be vrogilis). Vagizi poja pihtenkave sa. PHONETIC i-ve-TRA ji RE-ne E-ji OGH-rar ge-LIN-ko sko ma-jo-roz-LI-vis E-va ru-HI-lis. va-GI-zi PO-ja pih-ten-KA-ve sa. Tell the slut with-the hair of silver that they will stand until they drop. -

Masculinity, Violence, and Abjection in a Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones

CRIPPLES AND BASTARDS AND BROKEN THINGS: MASCULINITY, VIOLENCE, AND ABJECTION IN A SONG OF ICE AND FIRE AND GAME OF THRONES Tania Evans January 2019 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Of the Australian National University Declaration of Originality This work has not previously been accepted for any degree and is the result of my own independent investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. An earlier version of the chapter “The Bear and the Maiden Fair” is published in Aeternum: The Journal of Contemporary Gothic Studies. All images are owned by Home Box Office (HBO) and are reproduced here for the purposes of research. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 Chapter -

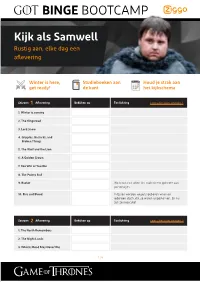

Binge Bootcamp

BINGE BOOTCAMP Kijk als Samwell Rustig aan, elke dag een aflevering Winter is here, Studieboeken aan Houd je strak aan get ready! de kant het kijkschema Seizoen1 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 1 1. Winter is coming 2. The Kingsroad 3. Lord Snow 4. Cripples, Bastards, and Broken Things 5. The Wolf and the Lion 6. A Golden Crown 7. You Win or You Die 8. The Pointy End 9. Baelor We leren een wijze les: raak niet te gehecht aan personages. 10. Fire and Blood In Essos worden wezens geboren waarvan iedereen dacht dat ze waren uitgestorven. En nu zijn ze nog cute! Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 1. The North Remembers 2. The Night Lands 3. What is Dead May Never Die 1 /4 BINGE BOOTCAMP Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 4. Garden of Bones 5. The Ghost of Harranhal 6. The Old Gods and the New 7. A Man Without Honor 8. The Prince of Winterfell 9. Blackwater King’s Landing, de hoofdstad van de Seven Kingsdoms, wordt aangevallen. Wat volgt is episch. 10. Valar Morghulis Seizoen3 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 3 1. Valar Dohaeris 2. Dark Wings, Dark Words 3. Walk of Punishment 4. And Now His Watch is 5. Kissed by Fire 6. The Climb 7. The Bear and the Maiden 8. Second Sons 9. The Rains of Castamere 10. Mhysa Seizoen4 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 4 1. Two Swords 2. The Lion and the Rose Wraak is zoet! 3. -

THE INTERNATIONAL LAW of GAME of THRONES Perry S. Bechky* I

PERRY - INTERNATIONAL - POSTEIC (MACRO) (DO NOT DELETE) 8/26/2015 11:13 AM THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF GAME OF THRONES Perry S. Bechky* I. BACKGROUND............................................................................................. 3 II. THE MORMONT RULE ................................................................................ 4 III. THE LANNISTER RULE ............................................................................. 6 IV. THE NIGHT’S WATCH .............................................................................. 9 V. DAENERYS’ RULE ................................................................................... 11 Game of Thrones depicts a Hobbesian world: lives are often nasty, brutish, and short; deaths are also nasty and brutish, but not always short. It is a world that is “dark and full of terrors.”1 It is a world of war and oppression, rape and castration, torture and slavery—and a world where viewers may cheer a dragon burning a mob of people. The titular “game” is about power: gaining power, using and abusing power, desperately trying to keep and bequeath power. As Queen Cersei said, “When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die.”2 In keeping with this theme of power, monarchs rule absolutely. To quote King Robert, “I’m the king. I get what I want.”3 And the monarchs have wanted to use their power, often horribly, to protect or boost their power: King Joffrey slaughtered his half-siblings, even babies, to purge possible rivals;4 King Stannis immolated his own daughter, thinking the sacrifice would bring him more power.5 All of this was apparently lawful, because done by a king. * Principal, International Trade & Investment Law PLLC; Visiting Scholar, Seattle University School of Law. I thank Mark Chinen and Sirina Tsai. All errors are mine. 1. This is the favorite threat by Melisandre, who delights in bringing one form of light into the dark world: fires to burn her enemies at the stake. -

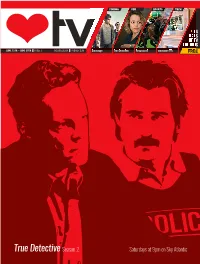

True Detectiveseason 2

CINEMA VOD SPORTS TECH + 14 DAYS OF TV LISTINGS JUNE 15TH – JUNE 28TH ISSUE 3 TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM Entourage True Detective Royal Ascot Innovative TVs FREE True Detective Season 2 Saturdays at 9pm on Sky Atlantic TV Guide Magazine Issue 3 V20.indd 1 12/06/2015 10:13 JUNE 15TH – JUNE 28TH ISSUE 3 Contents TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM EDITOR’S LETTER 4 News 16 Fashion The times are changing The biggest news from the world of television. Steal the style of the most bad-ass characters in the film industry. In on television. This week’s theme: the races. 2015, film actors at the height of their careers are habitually hopping across to television. Sometime in the last ten years, the 17 Drinks old barren wastelands Drink like the characters of Mad Men with of space between film and television were tips on tipples and local watering holes. developed into a high- speed rail service. No show illustrates this better than True Detective, which Sports returns to our screens on 18 June 22. To celebrate its Race information, quirky facts and hot tips return, we’ve dedicated a feature to the hit on horses for this year’s Royal Ascot. crime-drama (p. 6), and a 6 True Detective second on the intertwining trajectories of film and television (p. 14). Long Transforms TV 21 Youtube may TV reign! How HBO’s True Detective changed television Susan Brett, Editor Our guide to the best gaming channels. for the better when it fi rst aired in 2014. -

Game of Thrones Contents

Game of Thrones From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigation Jump to search American fantasy television series adapted from "A Song of Ice and Fire" This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Game of Thrones (disambiguation). Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss for HBO. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, a series of fantasy novels by George R. R. Martin, the first of which is A Game of Thrones. The show was shot in the United Kingdom, Canada, Croatia, Iceland, Malta, Morocco, and Spain. It premiered on HBO in the United States on April 17, 2011, and concluded on May 19, 2019, with 73 episodes broadcast over eight seasons. Set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos, Game of Thrones has a large ensemble cast and follows several story arcs throughout the course of the show. The first major arc concerns the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros through a web of political con- flicts among the noble families either vying to claim the throne or fighting for independence from whoever sits on it. A second focuses on the last descendant of the realm’s deposed rul- ing dynasty, who has been exiled to Essos and is plotting to return and reclaim the throne. The third follows the Night’s Watch, a military order defending the realm against threats from beyond Westeros’s northern border. Game of Thrones attracted a record viewership on HBO and has a broad, active, and inter- national fan base.