Economics Guide First Examinations 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Sketch of Profit Theories in Mainstream Economics

International Business Research; Vol. 9, No. 4; 2016 ISSN 1913-9004 E-ISSN 1913-9012 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Historical Sketch of Profit Theories in Mainstream Economics Ibrahim Alloush Correspondence: Ibrahim Alloush ,Department of Economic Sciences, College of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Zaytouneh University, Amman, Jordan. Tel: 00962795511113, E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 4, 2016 Accepted: February 1, 2016 Online Published: March 16, 2016 doi:10.5539/ibr.v9n4p148 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v9n4p148 Abstract In this paper, the main contributions to the development of profit theories are delineated in a chronological order to provide a quick reference guide for the concept of profit and its origins. Relevant theories are cited in reference to their authors and the school of thought they are affiliated with. Profit is traced through its Classical and Marginalist origins into its mainstream form in the literature of the Neo-classical school. As will be seen, the book is still not closed on a concept which may still afford further theoretical refinement. Keywords: profit theories, historical evolution of profit concepts, shares of income and marginal productivity, critiques of mainstream profit theories 1. Introduction Despite its commonplace prevalence since ancient times, “whence profit?” i.e., the question of where it comes from, has remained a vexing theoretical question for economists, with loaded political and moral implications, for many centuries. In this paper, the main contributions of different economists to the development of profit theories are delineated in a chronological order. The relevant theories are cited in reference to their authors and the school of thought they are affiliated with. -

Abnormal Profit See Supernormal Profit Absolute Advantage 171-4, 177, 178 Accelerator Theory 124, 126, 128 Accepting Houses 140

235 INDEX A Barriers to trade see Protection Barter 132 Abnormal profit see Supernormal profit Bill of exchange 53, 140, 143 Absolute advantage 171-4, 177, 178 Birth rate 80, 82, 83, 229 Accelerator theory 124, 126, 128 Black economy see Underground Economy Accepting houses 140, 143 Black market 28, 31, 32 Acquisitions 42, 63 Bonds 140, 149, 150, 153 Adaptive expectations 169, 170 Budget 121, 135, 145, 212, 213, 217, 219, 220 Advertising 42, 58, 65, 73, 78, 89 Budget line 34, 35 Aggregate demand 117, Ch.22, 161-3, 182, 197, Buffer stock 29 209, 219-25, 227 Bulk-buying 41, 46, 71 Aggregate supply Ch. 22, 161, 223-5 Aid, bilateral and multilateral 104, 232, 233 Allocative efficiency 182-4, 197, 204, 206, 208, 209, c 211, 212, 223, 229, 230 Capital 1, 43, 45, 46, 79, 86, 90, 91, 96, 97, 100, 108, Appreciation of currency 194-6, 198 123, 124, 127, 131, 133, 135, 136, 203, 206, 207, Arbitrage 146, 147 220, 231-4 Asset demand for money 149, 150 Capital depreciation see Depreciation of capital Asset stripping 42 Cartels 60, 76, 78, 230-2 Assisted areas 53, 212 Cecchini Report 107 Average cost 40, 43, 47-52, 57, 65, 66, 73, 74, 78 Central bank see Bank of England Average product 39, 40, 45, 46, 51, 52 Centrally planned economies 3--5 Average propensity to save 115, 227 Certificates of deposit 140, 143, 144 Average revenue 48, 49, 51, 65, 68, 73--6 Cheques 139, 144, 147 Average revenue product 93 Choice (and scarcity) 1-3 Circular flow of income 221 Clearing banks 14 B Collusion 76, 78 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 29, 181, 203--5, Balance of payments 1, 30, 64, 70, 161, 163, 180, 207-9, 211 182, Ch. -

13.Factor Pricing ; Rent

13.Factor pricing ; rent - Ricardian rent-economic rent – Quasi – rent; Wage– marginal productivity theory of wage; Interest - Liquidity preference theory; Profit –Risk-bearing theory of profit. DISTRIBUTION The theory of distribution or the theory of factor pricing deals with the determination of factor prices, such as wages, rents, interest and profit. i) Marginal Productivity Theory of Distribution According to this theory, the price of a factor of production depends upon its marginal productivity. A factor of production should get its reward according to the contribution it makes to the total output, i.e., its marginal productivity. Change in the revenue resulting from the employment of an extra unit of the factor is called Marginal Revenue Product (MRP) or Value of Marginal Product (VMP) and the change in total cost brought about by using an extra unit of the factor is called Marginal Factor Cost (MFC). Change in Total Revenue Δ TR VMP = MRP = = Change in Input Δ X Change in Total Cost Δ TC MFC = = Change in Input Δ X In factor market, a firm’s equilibrium occurs when MRP=MFC. In product market, a firm’s equilibrium will be at MR = MC (MR is the Marginal Revenue and MC is the Marginal Cost). The marginal productivity theory is defective because it indicates how many units of a factor (input) a firm will use at a given price in order to maximize its profit. For example, it tells us how many workers a firm will employ at a given wage rate to maximize its profit. But it does not tell us how the wage itself is determined. -

IB Economics HL Study Guide

S T U D Y G UID E HL www.ib.academy IB Academy Economics Study Guide Available on learn.ib.academy Author: Joule Painter Contributing Authors: William van Leeuwenkamp, Lotte Muller, Carlijn Straathof Design Typesetting Special thanks: Andjela Triˇckovi´c This work may be shared digitally and in printed form, but it may not be changed and then redistributed in any form. Copyright © 2018, IB Academy Version: EcoHL.1.2.181211 This work is published under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 This work may not used for commercial purposes other than by IB Academy, or parties directly licenced by IB Academy. If you acquired this guide by paying for it, or if you have received this guide as part of a paid service or product, directly or indirectly, we kindly ask that you contact us immediately. Laan van Puntenburg 2a ib.academy 3511ER, Utrecht [email protected] The Netherlands +31 (0) 30 4300 430 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 1. Microeconomics 7 – Demand and supply – Externalities – Government intervention – The theory of the firm – Market structures – Price discrimination 2. Macroeconomics 51 – Overall economic activity – Aggregate demand and aggregate supply – Macroeconomic objectives – Government Intervention 3. International Economics 77 – Trade – Exchange rates – The balance of payments – Terms of trade 4. Development Economics 93 – Economic development – Measuring development – Contributions and barriers to development – Evaluation of development policies 5. Definitions 105 – Microeconomics – Macroeconomics – International Economics – Development Economics 6. Abbreviations 125 7. Essay guide 129 – Time Management – Understanding the question – Essay writing style – Worked example 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION The foundations of economics Before we start this course, we must first look at the foundations of economics. -

Cambridge International AS & a Level Economics Workbook Answers.Pdf

Answers Chapter 1 Answers to exercises 1 The fundamental economic problem occurs because resources have to be allocated amongst competing uses since wants are infinite whilst resources are scarce. i You and your family: unless you are very wealthy, you and your family will never have enough money/income to satisfy all of your wants. For example, you might want to go to see a film but do not have enough money to do so; your family may want to buy the latest flat-screen TV but does not have enough spare income to purchase it. ii Government: all governments face the economic problem since they never have enough money in their budgets to be able to fund all of the wants that are required. As a result choices and priorities have to be made. Typical choices to be made are, for example, between spending more on an infant health programme or on an infant educational programme. The limited budget means that both cannot be funded. iii Manufacturing business: revenue and capital funds for any business are limited either through what is available inside a business or what can be borrowed outside. So, a firm might like to replace all of its outdated machinery but because it lacks the capital available to be able to do so can only replace some of it. 1 2 A typical answer, which includes examples from your country, could be: Description Typical Examples Land Natural resources Copper, water, tropical climate Labour Workers, human resources Labourers, supervisors, managers Capital Man-made aids for production Factories, machines airports Enterprise Organisation of production, taking risks Business managers, entrepreneurs 3 A possible answer: Specialisation is where a firm concentrates its production on those goods where it has an advantage over others. -

2.11 Market Failure – Market Power (HL) Deira International School Farooq Akhtar

2.11 Market failure – market power (HL) Deira International School Farooq Akhtar IB DP 12 EC 1 Group 3 (IB1) Summary 2.11 Market failure – market power (HL) Subject Year Start date Duration Economics IB1 Week 4, February 3 weeks 12 hours Course Part 2. Microeconomics Description 2.11 Market failure – Market power, you should be able to: • Be familiar with the following terms: short run, long run, law of diminishing marginal returns, total product, average product, marginal product, explicit costs, implicit costs, economic costs, total cost, average cost, marginal cost, fixed costs, variable costs, imperfect market, total revenue, average revenue, marginal revenue, economies of scale, perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, monopolistic competition, normal profit, abnormal profit, economic profit, predatory pricing, satisficing behaviour, productive efficiency, allocative efficiency, natural monopoly, collusion, tacit collusion, price war, contestable market, interdependent, concentration ratio, profit maximisation, fungibility, breaking even, perfectly price elastic demand, price taker, marginal social benefit, marginal social cost, price elasticity of demand, kinked demand curve, price maker, substitutes, legislation, regulation, nationalisation, price competition, non-price competition, perfect information. • Explain the characteristics of the four market structures: perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, monopolistic competition. • Distinguish between total costs, marginal costs and average costs. • Draw diagrams illustrating the relationship between marginal costs and average costs. • Calculate total fixed costs, total variable costs, total costs, average fixed costs, average variable costs, average total costs and marginal costs from a set of data. • Distinguish between total revenue, average revenue and marginal revenue. • Draw diagrams illustrating the relationship between total revenue, average revenue and marginal revenue. • Calculate total revenue, average revenue and marginal revenue from a set of data. -

FYBCOM Business Economics II SEM II UNIT 1

[TUTORIAL LESSON] April 1, 2020 SES’S L.S.RAHEJA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND COMMERCE Course: Business Economics II Unit: I Prepared by: Rahul Dandekar _________________________________________________________________________________________ Important Concepts 1) Perfect competition The Perfect Competition is a market structure where a large number of buyers and sellers are present, and all are engaged in the buying and selling of the homogeneous products at a single price prevailing in the market. 2) Normal profit Normal Profit exists when total revenue, TR, equals total cost, TC. Normal profit is defined as the minimum reward that is just sufficient to keep the entrepreneur supplying their enterprise. In other words, the reward is just covering opportunity cost - that is, just better than the next best alternative. 3) Supernormal profit If a firm makes more than normal profit it is called super-normal profit. Supernormal profit is also called economic profit, and abnormal profit, and is earned when total revenue is greater than the total costs. 4) Sub-normal profit If a firm makes less than normal profit it is called sub-normal profit. Sub-normal profit is also called as loss, and is incurred when total revenue is less than the total costs. 5) Shut down point A shutdown point is a level of operations at which a company experiences no benefit for continuing operations, and therefore decides to shut down temporarily (or in some cases permanently). It results from the combination of output and price where the company earns just enough revenue to cover its total LSRC/2019-20/tutoriallesson Page 1 [TUTORIAL LESSON] April 1, 2020 variable costs. -

Economics for the IB Diploma

Glossary abnormal profi t Refers to positive time period (aggregate demand), measured average costs Costs per unit of output, economic profi t, arising when total on the horizontal axis, plotted against the or the cost of each unit of output on revenue is greater than total economic price level, measured on the vertical axis. average. They are calculated by dividing costs (implicit plus explicit costs); is total cost by the number of units of output also known as ‘supernormal profi t’. See aggregate supply The total quantity produced. economic profi t. of goods and services produced in an economy over a particular time period, at average fi xed costs Fixed cost per unit absolute advantage Refers to the ability different price levels, ceteris paribus. of output, or the fi xed cost of each unit of of a country to produce a good using fewer output on average. They are calculated by resources than another country, or, what aid See foreign aid. dividing fi xed cost by the number of units is the same thing, the ability of a certain allocation of resources See resource of output produced. amount of resources in a country to allocation. produce more than the same resources can average product The total quantity produce in another country. allocative effi ciency An allocation of of output of a fi rm per unit of variable input (such as labour); shows how much resources that results in producing the absolute poverty The inability of an output each unit of the variable input individual or a family to afford a basic combination and quantity of goods and (for example, each worker) produces on standard of goods and services, where services mostly preferred by consumers. -

Persistence of Profits and the Systematic Search for Knowledge

CESIS Electronic Working Paper Series Paper No. 85 PERSISTENCE OF PROFITS AND THE SYSTEMATIC SEARCH FOR KNOWLEDGE - R&D links to firm above-norm profits Johan E Eklund and Daniel Wiberg JIBS and CESIS March 2007 Persistence of Profits and the Systematic Search for Knowledge - R&D links to Firm Above-Norm Profits Johan E. Eklund* and Daniel Wiberg* *Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), and Centre for Science and Innovation Studies (CESIS), Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. Adress: Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), Gjuterigatan 5, P.O. Box 1026, SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden Telephone: + 46 10 17 66 Fax. +46 12 18 32 E-Mail: [email protected] , [email protected] Abstract Economic theory tells us that abnormal firm and industry profits will not persist for any significant length of time. Any firm or industry making profits in excess of the normal rate of return will attract entrants and this competitive process will erode profits. However, a substantial amount of research has found evidence of persistent profits above the norm. Barriers to entry and exit, is an often put forward explanation to this anomaly. In the absence of, or with low barriers to entry and exit, this reasoning provides little help in explaining why these above-norm profits arise and persist. In this paper we explore the links between the systematic search for knowledge and the persistence of profits. By investing in research and development firms may succeed in creating products or services that are preferred by the market and/or find a more cost efficient method of production. -

Explicit and Implicit Costs TIME

8 MODULE 2: Fundamentals of Economics in Agriculture LESSON 3: Decision Making – Explicit and Implicit Costs TIME: 1 hour 36 minutes AUTHOR: Prof. Francis Wambalaba This lesson was made possible with the assistance of the following organisations: Farmer's Agribusiness Training by United States International University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License . Based on a work at www.oerafrica.org MODULE 2 Fundamentals of Economics in Agriculture DECISION MAKING – LESSON EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT COSTS 3 AUTHOR : TIME: Prof. Francis 1 hour 36 Wambalaba minutes INTRODUCTION: OUTCOMES: : By the end of this lesson you This lesson will focus on building skills will be able to: and economic rationales for decision • Differentiate between making under given farming scenarios economic costs and that may have multiple options. We will accounting costs. spend some time looking specifically at • Make decisions based on Economic versus Accounting Costs & the economic logic and Relevant Cost Analysis. explain the rationale for each decision. 73 Page Page Module 2: Fundamentals of Economics in Agriculture Lesson 3: Decision Making – Explicit and Implicit costs Economic vs. Accounting Costs While in many cases, economists talk the same vernacular of numbers that lend to measurement of profit, in a few cases, the two appear to speak about the same numbers in foreign languages. Some of these incidences are covered here. Activity 1 Class Discussion (5 minutes) Work in groups of four and discuss: “What, do you think, are the objectives of a farmer?” While the various objectives identified by each member are valid, notice the centrality of the concept of profit in each viewpoint, especially those that desire their farm to be a firm. -

Semester ECD1341 Micro Economics-II Module-I

B A Economics Third Semester ECD1341 Micro Economics-II Module-I Market Structures Dr.Vineetha.T Lecturer School of Distance Education University of Kerala What is a Market? • Place where there are many buyers and sellers. • Actively engaged in buying and selling acts. • Thus, it does not mean a particular place but the entire area where buyers and sellers of a commodity are in close contact and they have one price for the same commodity. Market Structures Based on Competition Market Structures Perfect Competition Imperfect Competition Monopolistic Monopoly Oligopoly Competition UNIT-I PERFECT COMPETITION Perfect Competition • It is a market structure where there are large number of sellers and buyers. • Homogeneous Product • The price of the product is determined by the industry. • One price prevails in the market and all the firms sell the product at the prevailing price. • It is also known as “Pure Competition” Features of Perfect Competition Demand Curve Facing a Perfectly Competitive Firm • The firms demand curve is different from the industry demand curve. • A Perfectly competitive firm‟s demand schedule is perfectly elastic even though the demand curve for the market is downward sloping. • The result is that the individual firm perceives the demand curve for its product as being perfectly horizontal. Market Demand Versus Individual Firm Demand Curve Profit –Maximizing Level of Output • The goal of the firm is to maximize profits • Profit is the difference between Total revenue and Total cost. • What happens to profit in response to a change in output is determined by Marginal Revenue (MR) and Marginal Cost (MC) • A firm maximizes profit when MC=MR • A perfect competitor accepts the market price as given, • As a result, MR= P Short-Run Equilibrium of the firm under Perfect Competition: Marginal Approach • Firm is in equilibrium - when Maximize Profit • To maximize profits, a firm should produce where MC=MR & TR=TC If MR does not equal to MC, a firm can increase profit by changing output. -

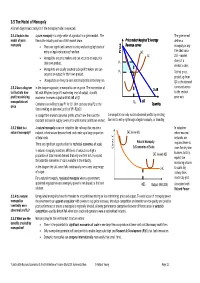

3.5 the Model of Monopoly a Formal Diagrammatic Analysis of the Monopoly Model Is Expected

3.5 The Model of Monopoly A formal diagrammatic analysis of the monopoly model is expected. 3.5.1 Explain the A pure monopoly is a single seller of a product in a given market. The The government model of pure firm is the industry and has a 100% market share. Price maker Marginal & Average defines a monopoly • There are significant barriers to entry and exit eg high costs of Revenue curves monopoly as any firm that has a entry or legal restraints eg franchise. PricePrice MC AC 25% + market • Monopolists are price makers and can set price or output for share of a their own product. P1 market’s sales. • Monopolists are usually assumed to be profit makers and can P2 To find price, set price or output for their own product. project up from • Monopolists are likely to earn abnormal profits in the long run. Q1 to the demand curve and across 3.5.2 Use a diagram In the diagram opposite, a monopolist can set price. The intersection of D=AR to illustrate how MC with MR gives the profit maximising level of output. A profit to the vertical profit maximising maximiser increases output until MC=MR at Q1 price axis monopolists set Q MR Consumers are willing to pay P1 for Q1. Unit costs are only P2 so the 1 Quantity price firm is making an abnormal profit of (P1-P2)xQ1 In competitive markets abnormal profits attract new firms and the A monopolist can only sustain abnormal profits by erecting resultant increase in supply lowers price until normal profits are earned.