Working Papers in International Urban Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltlink Rider Guide-944004A2.Pdf

WHAT IS BALTIMORELINK? BaltimoreLink is a complete overhaul and rebranding of the core transit system operating within Baltimore City and the surrounding region. Many of MTA’s current bus routes are outdated, and BaltimoreLink will improve service through a more reliable and efficient network. BaltimoreLink also includes transfer facilities, dedicated bus lanes, signal priority, and improved bus stop signs, among many other improvements. To deliver an interconnected transit network, existing MTA bus and rail services will be restructured and renamed: • CityLink: Twelve new high-frequency, color-coded bus routes will connect with each other, as well as Metro SubwayLink, Light RailLink, MARC Train, Commuter Bus, Amtrak, and other services, into one integrated transit network. • LocalLink (currently Local Bus): LocalLink routes will provide comprehensive crosstown connections and improved connections to neighborhoods and communities throughout the system. • Express BusLink (currently Express Bus): Express BusLink will include several existing Express Bus services that provide suburb-to- city connections and recently launched routes providing suburb-to-suburb connections. Typically, Express Bus routes have fewer stops and use higher speed roads. • Light RailLink (currently Light Rail): Light Rail service will operate along the same line but with improved connections to buses. • Metro SubwayLink (currently Metro Subway): This service will not change but will have improved connections to buses. baltimorelink.com | 1 BETTER BUS STOPS BALTIMORELINK RESOURCE INFORMATION To create a better rider experience by providing information you can use, the MTA will be All MTA routes will change under installing new bus stop signs throughout the BaltimoreLink. Please look for Rider Alerts for entire MTA bus network. -

Anne Arundel County Corridor Growth Management Plan Final Report

FINAL REPORT Anne Arundel County Corridor Growth Management Plan July 20, 2012 LEGEND Baltimore City US 50 MD 2 South MD 2 North Howard County I-97 MD 32 MD 100 4.6-Miles MD 295 MD 3 MD 607-MD 173 14-Miles 2.5-Miles 16-Miles Benfield Blvd. 13-Miles MD176 14-Miles 17-Miles MD170 4.6-Miles MD 713 Ridge Rd. 11-Miles AACOBoundary Anne Arundel County 17-Miles 7-Miles 19-Miles 4-Miles Prince George's County Prepared by: µ 0 1 2 4 Miles a Joint Venture 7055 Samuel Morse Dr., Suite 100 | Columbia, MD 21406 | 410.741.3500 Corridor Growth Management Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................1-1 1.1 OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Purpose and Scope ................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.2 Project Costs .......................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.3 Alternatives Tested ............................................................................... 1-2 1.1.4 Priorities ................................................................................................ 1-4 1.1.5 Next Steps ............................................................................................. 1-4 1.2 US 50 .................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3 MD 2 - NORTH ................................................................................................... -

Resolution #20-9

BALTIMORE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION BALTIMORE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION BOARD RESOLUTION #20-9 RESOLUTION TO ENDORSE THE UPDATED BALTIMORE REGION COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT – HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board (BRTB) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region, encompassing the Baltimore Urbanized Area, and includes official representatives of the cities of Annapolis and Baltimore; the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s; and representatives of the Maryland Departments of Transportation, the Environment, Planning, the Maryland Transit Administration, Harford Transit; and WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Baltimore region, has responsibility under the provisions of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act for developing and carrying out a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive transportation planning process for the metropolitan area; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration, a modal division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, requires under FAST Act the establishment of a locally developed, coordinated public transit-human services transportation plan. Previously, under MAP-21, legislation combined the New Freedom Program and the Elderly Individuals and Individuals with Disabilities Program into a new Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program, better known as Section 5310. Guidance on the new program was provided in Federal Transit Administration Circular 9070.1G released on June 6, 2014; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration requires a plan to be developed and periodically updated by a process that includes representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and participation by the public. -

Strategic Advice for the Real Estate Community and Retailers. Since 1969

Strategic advice for the real estate community and retailers. Since 1969. Retail properties Residential properties Shopco Properties LLC Commercial properties www.shopcogroup.com Marc Yassky Joseph Speranza Principal Principal [email protected] [email protected] 424 Madison Ave 16th floor 485 Madison Ave 22nd floor New York NY 10017 New York NY 10122 212 223 1270 212 594 9400 212 202 7777 fax 888 308 1030 fax ABOUT US Shopco Properties LLC is a real estate consultancy firm focused on retail centers and multifamily residential buildings, offering strategic advice regarding development, redevelopment, finance, construction, leasing, management, marketing, and acquisition and disposition. Shopco’s depth of experience comes from the firm’s history as a developer and acquirer of regional malls, other shopping centers, and multifamily projects, across the nation. Founded in 1969, its primary focus has been retail, residential, and commercial real estate. Along with the company’s development and acquisition activities, Shopco acts as a consultant to a variety of clients, including Wall Street firms engaged in real estate lending, development and workouts, developers, private equity funds, family offices with real estate holdings, and retail ten- ants seeking locations. Clients include or have included: Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan Chase Bank, Swedbank, and Tishman Speyer, amongst others. Since the company is a small one, the principals’ experience and expertise is directly available to our clients. Our history of developing, as well as redeveloping and operating retail, residential and commercial projects, gives us particular insight when serving our customers. Shopco Properties LLC www.shopcogroup.com HISTORY Shopco was founded in 1969 to develop enclosed regional malls. -

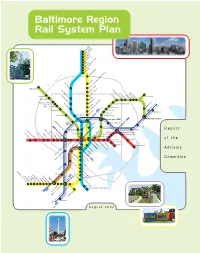

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 140 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 47 Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 140 Filed 08/15/18 Page 2 of 47

Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 140 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 47 Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 140 Filed 08/15/18 Page 2 of 47 EXHIBIT A Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 140 Filed 08/15/18 Page 3 of 47 Brookstone Holdings Corp., et al. - Service List to e-mail Recipients Served 8/8/2018 ACCTRON COMPANY LIMITED AFTER SHOKZ LLC ASIA COMBINE CO., LTD DESMOND CHEUNG BILL KIMBALL GLENN CHEN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ASIA COMBINE CO., LTD AXENT WEAR, INC BALLARD SPAHR LLP HOWARD CHEN VICTORIA HU DAVID L. POLLACK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BOSTON RETAIL PARTNERS, LLC BURR & FORMAN LLP CHOATE, HALL & STEWART LLP STEPHANIE JOYCE J. CORY FALGOWSKI JONATHAN D. MARSHALL [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CHOATE, HALL & STEWART LLP COZZIA USA LLC DEMANDWARE INC KEVIN SIMARD JOHN CRIBBS TERRI PETZOLD [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] EMERGE TECHNOLOGIES, INC. FEDERAL EXPRESS FROST BROWN TODD LLC JAY MACKEN CANDISE JEFFRIES A. J. WEBB [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FROST BROWN TODD LLC GGP GGP LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, AS AGENT RONALD E. GOLD NANCY BERNERO KRISTEN N. PATE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] GRANTEC ZHANGZHOU CO. LTD GRAY REED & MCGRAW LLP GRAY REED & MCGRAW LLP V.M. LEE AMBER M. CARSON JASON BROOKNER [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] KELLEY DRYE & WARREN LLP KELLEY DRYE & WARREN LLP KELLEY DRYE & WARREN LLP JENNIFER D. -

6 12 14 18 Proposal Would Bring Walmart Supercenter to Owings

INSIDE THIS ISSUE SEPTEMBER 2016 A free publication serving Owings Mills, Pikesville, Randallstown, Reisterstown, Windsor Mill, Woodlawn and Catonsville 6 A speaker at the Aug. 31 Seeking Justice community input meeting in Randallstown protests plans for Korryn for Kimco Realty to bring Gaines the area’s third Walmart to Owings Mills Mall. 12 Community Gives Input on New Courthouse 14 Will Macy’s Close at Security Proposal Would Bring Mall? Walmart Supercenter to Owings Mills Mall Community gets vocal Owings Mills Mall is in demolition mode, as heavy equipment is taking down the 30-year-old mall to rubble. While the community has lamented the slow decline of the mall, which 18 closed in January and once catered to upscale shoppers with a Saks Fifh Event Gets Avenue, Lord and Taylor and Macy’s as anchors, residents are looking forward Students Ready to a new shopping experience. Te redevelopment plan, they were told, was to for School replace the property with an open-air shopping center similar to Hunt Valley “I WILL DO EVERYTHING IN Towne Centre and the Avenue at White Marsh. Many looked forward a robust MY POWER TO MAKE SURE Be among the first to mix of department and big box stores, smaller national discount retailers and THE RANDALLSTOWN be in the know. Sign up boutique shops. WALMART DOES NOT Tose expectations were dashed when District 4 Councilman Julian Jones CLOSE.” for news updates from sent an email inviting constituents to two community input meetings to weigh nwvoicenews.com. Julian Jones, District 4 continued on page 20 Baltimore County Councilman Page 2 Northwest Voice September 2016 From the Publisher, Kenneth Brown What is the Role of Developers, the Community in Retail Success? I attended the community input meetings held opportunity to get involved sooner, either by their Boulevard to analyze the situation and start last month in Owings Mills and Randallstown own proactivity or by elected ofcials or business communicating with mall and business owners and concerning the future redevelopment of the leaders soliciting their input. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

“Get on the Bus” Transportation to Places of Interest from UMBC

“Get on the Bus” Transportation to Places of Interest from UMBC BWI and Light Rail Towson Town Center/Towson University Take UMBC Shuttle Bus BWI MARC Line to Take MTA bus #35 to Baltimore and Charles BWI MARC/Amtrak Station and take the free Streets. On Baltimore Street, transfer to MTA shuttle bus from there to BWI airport or to the bus #8 which goes to Towson University. BWI Light Rail Station. Hunt Valley Inner Harbor Take the UMBC Shuttle Bus BWI MARC Take MTA Bus #35 to downtown. Exit at Line to the BWI MARC/Amtrak Station (Mon- corner of Pratt and Charles Streets. Proceed Frie) and take the free shuttle to the BWI Light East on Pratt Street to Inner Harbor. Rail Station. Take the Blue Light Rail north to Hunt Valley, or: Arundel Mills Mall Take the MTA bus #35 to Pratt St. and Take UMBC Shuttle Bus BWI MARC Line Howard St. Then, take the Light Rail north to (Mon-Fri) to BWI MARC/Amtrak Station. Hunt Valley. From there, take MTA Bus #17 to Arundel Mills Mall, or: Greenbelt Metro Station Fri-Sun, take the UMBC Shuttle Bus Arundel Take the UMBC Shuttle Bus Mills Line to the Arundel Mills Mall. Halethorpe/Satellite Line to the Halethorpe MARC station. From Halethorpe, take the Security Square Mall Penn Line Marc Train to BWI MARC/Amtrak Take MTA Bus #77 to Security Blvd. and Station and take the free shuttle bus from there Belmont Avenue. to BWI airport. Proceed to the bus stop at Pier E on the lower level of the international Westview Shopping Center terminal. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_November 2, 2007__ I, __Aaron Cowan___________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism, Urban____________ Revitalization, and the Transformation of Postwar American Cities This work and its defense approved by: David Stradling, Chair: ___David Stradling______________ Wayne Durrill __ Wayne Durrill_____ ________ Tracy Teslow ___Tracy Teslow _______________ Marguerite Shaffer Marguerite Shaffer Miami University Oxford, Ohio A Nice Place To Visit: Tourism, Urban Revitalization, and the Transformation of Postwar American Cities A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Aaron B. Cowan M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2003 B.A., King College, 1999 Committee Chair: Dr. David Stradling Abstract This dissertation examines the growth of tourism as a strategy for downtown renewal in the postwar American city. In the years after World War II, American cities declined precipitously as residents and businesses relocated to rapidly-expanding suburbs. Governmental and corporate leaders, seeking to arrest this decline, embarked upon an ambitious program of physical renewal of downtowns. The postwar “urban crisis” was a boon for the urban tourist industry. Finding early renewal efforts ineffective in stemming the tide of deindustrialization and suburbanization, urban leaders subsidized, with billions of dollars in public finances, the construction of an infrastructure of tourism within American downtowns. By the latter decades of the period, tourist development had moved from a relatively minor strategy for urban renewal to a key measure of urban success. -

Clarksburg, Maryland

CLARKSBURG, MARYLAND PROPERTY OVERVIEW CLARKSBURG PREMIUM OUTLETS® JOINT VENTURE WITH NEW ENGLAND DEVELOPMENT CLARKSBURG, MD MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS SELECT TENANTS Frederick Baltimore: 47 miles Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5TH, Banana Republic Factory Store, Coach, 70 Washington, D.C.: 34 miles kate spade new york, Michael Kors, NikeFactoryStore, Polo Ralph Lauren Baltimore Factory Store, Steve Madden, Tory Burch, Under Armour Clarksburg RETAIL 270 Columbia TOURISM / TRAFFIC 95 GLA (sq. ft.) 390,000; 90 stores Clarksburg Premium Outlets is a LEED certified center and the first OPENING DATES bi-level Premium Outlets in the United States. Clarksburg is located in the very affluent and densely populated Washington, D.C. suburbs of Opened October 2016 Montgomery County, MD. The county has a population of over one Washington million people, and is the 10th wealthiest county in the U.S., second wealthiest county in the U.S. of counties with over one million people. RADIUS POPULATION Additionally, the site is within 30 miles of four of the top ten wealthiest 15 miles: 700,726 counties in the U.S. (Montgomery, Howard, Loudoun and Fairfax). CLARKSBURG PREMIUM OUTLETS 30 miles: 4,285,461 Montgomery County borders the nation’s capital of Washington, D.C., CLARKSBURG, MD 45 miles: 8,020,590 which had approximately 20.2 million tourists in 2014. The site is located on the I-270 Technology Corridor (a 12-lane highway), AVERAGE HH INCOME a hub for federal government agencies such as National Institute of Health, 30 miles: $122,657 National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Standards and Technology, Department of Energy and Department of Health and Human Services. -

Directory of Baltimore City Community Resources

Directory of Baltimore City Community Resources This directory was made possible through funding support from Open Society Institute – Baltimore and Baltimore City Health Department Updated 10.15.2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This directory was developed by Dr. Nancy Lever, Aya Ghunney, Jessica Lertola, Krystal Lewis, Kerri Stiegler, Sylvia McCree-Huntley, and clinicians and staff from the University of Maryland School Mental Health Program and Center for School Mental Health within the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Thanks to all who have recommended helpful resources to make this directory more comprehensive and useful. We are indebted to our funders, Open Society Institute - Baltimore and the Baltimore City Health Department. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Joshua M. Sharfstein, Baltimore City Health Commissioner, and the Baltimore City Council for their vision to improve expanded school mental health services and to support consultation and technical assistance efforts. The inclusion of resources within this directory is not meant to imply an endorsement of any program or the services provided. With the wide array of services available in Baltimore City, it is challenging to capture all services available. We apologize if we have inadvertently not included programs and resources that are available. This directory will continue to be updated by University of Maryland staff and through input from those utilizing this important resource. If there are any updates/additions/deletions, please email Dr. Lever, [email protected]. It is our hope that this resource will be a valuable addition to all who are working together to help youth be successful.