Page 1 FA M IL IA NUMBER 33 2017 U L S T E R G E N E a L O G I C a L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

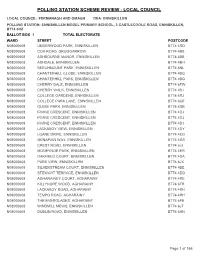

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: FERMANAGH AND OMAGH DEA: ENNISKILLEN POLLING STATION: ENNISKILLEN MODEL PRIMARY SCHOOL, 3 CASTLECOOLE ROAD, ENNISKILLEN, BT74 6HZ BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000608UNDERWOOD PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RD N08000608COA ROAD, DRUMGARROW BT74 4BS N08000608ASHBOURNE MANOR, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BB N08000608ASHDALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BH N08000608BEECHMOUNT PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6NL N08000608CHANTERHILL CLOSE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHANTERHILL PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHERRY DALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6FW N08000608CHERRY WALK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BJ N08000608COLLEGE GARDENS, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RJ N08000608COLLEGE PARK LANE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6GF N08000608GLEBE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DB N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608LACKABOY VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DY N08000608LOANE DRIVE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608MENAPIAN WAY, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4GS N08000608CREST ROAD, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JJ N08000608MONEYNOE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4ER N08000608OAKFIELD COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DA N08000608PARK VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JX N08000608SILVERSTREAM COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BE N08000608STEWART TERRACE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608AGHARAINEY COURT, AGHARAINY BT74 4RE N08000608KILLYNURE WOOD, AGHARAINY BT74 6FR N08000608LACKABOY ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608TEMPO ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608THE EVERGLADES, AGHARAINY BT74 6FE N08000608WINDMILL -

Filgate of Lisrenny Papers, 1757 – 1964, Ref PP0001

© Louth County Archives Service Filgate of Lisrenny Papers, 1757 – 1964, Ref PP0001/ Contents: Fonds Identity Statement & Context 2 Fonds Content & Structure 5 Fonds Conditions of Access & Use, Allied Materials, Links & Notes: 8 Filgate Family Tree 10 Sub-fonds PP00001/001/ Identity Statement, Context, Content & Structure 12 Sub-fonds PP00001/001/ Contents 14 Sub-fonds PP00001/002/ Identity Statement, Context, Content & Structure 55 Sub-fonds PP00001/002/ Contents 57 Sub-fonds PP00001/003/ Identity Statement, Context, Content & Structure 74 Sub-fonds PP00001/003/ Contents 75 Sub-fonds PP00001/004/ Identity Statement, Context, Content & Structure 93 Sub-fonds PP00001/004/ Contents 94 Sub-fonds PP00001/005/ Identity Statement, Context, Content & Structure 110 Sub-fonds PP00001/005/ Contents 111 1 © Louth County Archives Service Fonds Identity Statement & Context Repository Code: IE LHA Collection Reference Code: PP00001/ Title: Filgate of Lisrenny Papers Dates: 1757 - 1964 Level of Description: Fonds Extent: 8 archival boxes Name of Creator(s): Filgate Family Admin/Biographical History: Family Origins The Lisrenny estate where the Filgate family settled in the seventeenth century originally belonged to a branch of the Bellews of Castletown, Dundalk. It had been seized from the Bellews during the English Commonwealth confiscations of 1653. As the estate was situated within the barony of Ardee, it became part of the land grant that was made to English Commonwealth ex-soldiers who had service in Ireland prior to 1649. Many of these ex-soldiers came from families who had been settled in Ireland during the seventeenth century or earlier. A William Peppard or Pepper, was the ex-soldier who was granted Lisrenny (Harold O’Sullivan, A History of Local Government in the County of Louth, IPA, Dublin, 2000, p132-3). -

1926 Census County Fermanagh Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1926 COUNTY OF FERMANAGH. Printed and presented pursuant to the provisions of 15 and 16 Geo. V., ch. 21 BELFAST: PUBLISHED BY H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND. To be purchased directly from H. M. Stationery Office at the following addresses: 15 DONEGALL SQUARE WEST, BELFAST: 120 GEORGE ST., EDINBURGH ; YORK ST., MANCHESTER ; 1 ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF ; AD ASTRAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2; OR THROUGH ANY BOOKSELLER. 1928 Price 5s. Od. net THE. QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. iii. PREFACE. This volume has been prepared in accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 6 (1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland), 1925. The 1926 Census statistics which it contains were compiled from the returns made as at midnight of the 18-19th April, 1926 : they supersede those in the Preliminary Report published in August, 1926, and may be regarded as final. The Census· publications will consist of:-· 1. SEVEN CouNTY VoLUMES, each similar in design and scope to the present publication. 2. A GENERAL REPORT relating to Northern Ireland as a whole, covering in more detail the. statistics shown in the County Volumes, and containing in addition tables showing (i.) the occupational distribution of persons engaged in each of 51 groups of industries; (ii.) the distribution of the foreign born population by nationality, age, marital condition, and occupation; (iii.) the distribution of families of dependent children under 16 · years of age, by age, sex, marital condition, and occupation of parent; (iv.) the occupational distribution of persons suffering frominfirmities. -

Fermanagh Genealogy Centre Leaflet Part 2

List of Civil Parishes in Fermanagh Aghalurcher, Aghavea, Belleek, Boho, Cleenish, Clogher, Clones, Currin, Derrybrusk, Derryvullan, Devenish, Drumkeeran, Drummully, Enniskillen, Galloon, Inishmacsaint, Killesher, Kinawley, Magheracross, Magheraculmoney, Rossory, Templecarn, Tomregan, Trory FERMANAGH There are over 2200 townlands in Fermanagh. genealogy centre Helping you find your Fermanagh roots Baronies of Fermanagh Irvinestown Belleek Enniskillen Lisnaskea Clanawley Clankelly Coole Knockninny Lurg Magheraboy Magherastephana Tirkennedy Fermanagh Genealogy Centre, Enniskillen Castle Enniskillen County Fermanagh BT74 7HL Email: [email protected] Phone: +44 (0) 28 66 323110 Designed & Printed by Ecclesville Printing Services | 028 8284 0048 www.epsni.com Printing Ltd Ecclesville by Designed & Printed SEARCHING FOR YOUR ANCESTORS Preserving Fermanagh’s Volunteers helping you find your genealogical heritage Fermanagh Roots WHO WE ARE AN OPPORTUNITY TO Fermanagh Genealogy Centre is run by BE A VOLUNTEER Volunteers. It was established in 2012 Volunteering for the Genealogy Centre and has operated as a delivery partner is an opportunity to make new friends for Fermanagh and Omagh District and to help others in their search for Council since October 2013 their family history connections to Fermanagh. It is also an opportunity WHAT WE ARE to learn more about how to search for We are a charitable organisation, who your own family history. We provide assist visitors to find their family history regular training for our volunteers, so connections in Fermanagh. Our aim is to that they are familiar with the range create a welcoming place for visitors and of material available. Opportunities exist Frank McHugh with visitors to the Fermanagh Genealogy volunteers for people to volunteer in the Centre on a Genealogy Centre, Dorothy McDonald volunteers, irrespective of religious, and her husband, Malcolm. -

Introduction Porter Papers

INTRODUCTION PORTER PAPERS November 2007 Porter Papers (D1390/10, N/19, LR1/178/1) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................2 Family history...........................................................................................................3 The Belleisle estate .................................................................................................4 The townlands .........................................................................................................5 Fermanagh and Longford ........................................................................................6 Clogher Park............................................................................................................7 The 'Regency' period ...............................................................................................8 Railways and libel actions........................................................................................9 A scandalous affair ................................................................................................10 The Lisbellaw Gazette ...........................................................................................11 Other ventures .......................................................................................................12 Political affairs........................................................................................................13 Porter-Porter ..........................................................................................................14 -

Flora & Fauna, Water, Soils, Cultural

ROUTE CONSTRAINTS REPORT SOCIO -ECONOMIC , LANDUSE , LANDSCAPE , FLORA & FAUNA , WATER , SOILS , CULTURAL HERITAGE AND STATION LOCATION REPORT Prepared for Eirgrid to support a Planning Application for the Cavan-Tyrone 400kV Interconnector Project Client: Eirgrid 27 Fitzwilliam Street Lower Dublin 2 By: AOS Planning Limited 4th Floor Red Cow Lane 71 / 72 Brunswick Street North Smithfield Dublin 7 Tel 01 872 1530 Fax 01 872 1519 E-mail: [email protected] www.aosplanning.ie FINAL REPORT - SEPTEMBER 2007 All maps reproduced under licence from Ordnance Survey Ireland Licence No. SU0001105. © Ordnance Survey Ireland Government of Ireland. Cavan-Tyrone 400kV Interconnector Project Table of Contents Section 1 – Executive Summary ......................................................... 5 1.1 The Project .................................................................................. 5 1.2 Route Corridor Alternatives ........................................................... 5 1.3 Key Findings with Regard to Impacts Arising .................................. 5 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................... 6 1.5 Terms of Reference ...................................................................... 6 1.6 Strategic Planning Context ............................................................ 7 1.7 Socio-Economic ............................................................................ 7 1.8 Landuse ...................................................................................... -

Enniskillen, Nov 6Th 1834 Dear Sir. I Send You the Name Books Of

Enniskillen, Nov 6th 1834 River (ABHAINN NA SAILISE) he slipped on its slippery banks and the books fell off his horns and it was sometime before he could fix them up again. This Dear Sir. was affected by the genius or sheaver (shaver) who presided over the Sillees, I send you the name books of Templecarn, Devenish, Enniskillen, ' who did all in his power to prevent the establishment of the christian religion in Derryvullan, Boho and Inishmacsaint. I expect that Mr. Sharkey will have the that neighbourhood. As soon as Faber had understood that the demon of the usual watch on me. It is very difficult to adhere to the analogies of Derry and river thus annoyed the good beast, she cursed the river praying that the Sillees Down in the names of this county, because the pronunciation is nearly might be cursed with sterility of fish and fertility in the destruction of human Connaught. The termination reagh, I was obliged to make reevagh in some life, and that it might run against the hill. The curse was pronounced in the instances, and garve, I had to make garrow. The word TAOBH, i.e. side or brae- following Irish words:- face frequently enters into the names here; this we have anglicized Tieve in MI-ADH EISC A'S ADH BAIDHTE Derry, Down & Antrim. I have used the same spelling of it here, but I am afraid it is too violent as every authority makes it Teev. The more northerly AG RITH ANAGHAIDH AN AIRD GO LA BRATHA. pronunciation is tee-oov, the Fermanagh one Teev. -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co. -

Townlands Cabragh to Clyttaghan Adobe

TOWNLANDS CABRAGH to CLYTTAGHAN O.S. TOWNLAND COUNTY DIVISION MAP PARISH REF Cabragh Antrim Enagh 17 & Ballymoney 22 Cabragh Down Carrickcrossan 47 Clonallan Cabragh Down Clonduff 42 Clonduff Cabragh Armagh Glenaul 11 Eglish Cabragh Armagh Grange 8 & Grange 12 Cabragh Down Ballyworfy 14 & Hillsborough 15 & 21 & 22 Cabragh Tyrone Aghnahoe 53 Killeeshil Cabragh Tyrone Kilskeery 49 & Kilskeery 56 Cabragh Antrim Kirkinriola 27 & Kirkinriola 32 Cabragh Armagh Markethill 17 Mullaghbrack Cabragh Armagh Mullaghbrack 13 Mullaghbrack Cabragh or Antrim PortCammon 7 Billy Cavanmore Cackinish Fermanagh Crum 42 Kinawley Caddy Antrim Drumanaway 43 Drummaul Cadian Tyrone Minterburn 61 Clonfeacle Cady Tyrone Tullaghoge 38 Desertcreat Cady Fermanagh Kesh 5 Magheraculmoney Cah Londonderry Garvagh 18 Errigal Cahard Down Leggygowan 22 & Kilmore 23 Caheny Londonderry Bovagh 19 Aghadowey Caherty Antrim Ballyclug 33 Ballyclug Cahery Londonderry Keady 10 Drumachose Cahoo Tyrone Tullaghoge 38 & Donaghenry 39 Cahore Londonderry Draperstown 40 Ballynascreen Cahore Fermanagh Ederny 6 Drumkeeran Caldanagh Antrim Dunloy 22 & Finvoy 23 Caldragh Fermanagh Kinawley 38 Kinawley Caldrum Tyrone Favour Royal 59 Clogher Caldrum Glebe Fermanagh Rahalton 15 Inishmacsaint Caledon Tyrone Caledon 67 & Aghaloo 71 Calf Island Down Kilmood 17 Ardkeen Calhame Antrim Ballynure 45, Ballynure 46, 51 & 52 Calheme Antrim Stranocum 17 Ballymoney Calheme Tyrone Edymore 5 Camus Calkill Tyrone Castletown 25 & Cappagh 34 Calkill Fermanagh Killesher 26 & Killesher 32 Callagheen Fermanagh Inishmacsaint -

About the Walks

WALKING IN FERMANAGH About the Walks The walks have been graded into four categories Easy Short walks generally fairly level going on well surfaced routes. Moderate Longer walks with some gradients and generally on well surfaced routes. Moderate/Difficult Some off road walking. Good footwear recommended. Difficult This only applies to Walk 20, a long walk only suitable for more experienced walkers correctly equipped. For those looking for a longer walk it is possible to combine some walks. These are numbers 10 and 11, 12 and 13, 18 and 20, and 24 and 25. Disclaimer Note: The maps used in this guide are taken from the original publication, published in 2000. Use of these maps is at your own risk. Bear in mind that the countryside is continually changing. This is especially true of forest areas, mainly due to the clearfelling programme. In the forests some of the footpaths may also change, either upgraded as funds become available or re-routed to overcome upkeep problems and reduce costs. These routes are not waymarked but should be by the summer of 2007. Metal barriers may well be repositioned or even removed. A new edition of the book, ‘25 Walks in Fermanagh’ will be coming out in the near future. please follow the principles of Leave No Trace Plan ahead and prepare Travel and camp on durable surfaces Dispose of waste properly Leave what you find Minimise campfire impacts Respect Wildlife Be considerate of other visitors WALKING IN FERMANAGH Useful Information This walking guide was commissioned by Fermanagh District Council who own the copyright of the text, maps, and associated photographs. -

Area Profile of Ballinamallard

‘The Way It Is’ Area Profiles A Comprehensive Review of Community Development and Community Relationships in County Fermanagh December 98 AREA PROFILE OF BALLINAMALLARD (Including The Townland Communities Of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy, Killadeas And Kilskeery). Description of the Area Ballinamallard is a small village, approximately five miles North of Enniskillen; it is located off the main A32, Enniskillen to Irvinestown road on the B46, Enniskillen to Dromore road. Due to its close proximity to Enniskillen, many of the residents work there and Ballinamallard is now almost a ‘dormitory’ village - house prices are relatively cheaper than Enniskillen, but it is still convenient to this major settlement. With Irvinestown, located four miles to its North, the village has been ‘squeezed’ by two economically stronger settlements. STATISTICAL SUMMARY: BALLINAMALLARD AREA (SUB-AREAS: WHITEHILL, TRORY, BALLYCASSIDY, KILLADEAS) POPULATION: Total 2439 Male 1260 (51.7%) Female 1179 (48.3%) POPULATION CHANGE 1971-1991: 1971 1991 GROWTH 2396 2439 1.8% HOUSEHOLDS: 794 OCCUPANCY DENSITY: 3.07 Persons per House. DEPRIVATION: OVERALL WARD: Not Deprived (367th in Northern Ireland) Fourth Most Prosperous in Fermanagh ENUMERATION DISTRICTS: NINE IN TOTAL Four Are Deprived One In The Worst 20% in Northern Ireland UNEMPLOYMENT (September 1998): MALES 35 FEMALES 18 OVERALL 53 RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION: CATHOLIC: 15.7% PROTESTANT: 68.2% OTHERS / NO RESPONSE: 16.1% Socio-Economic Background: The following paragraphs provide a review of the demographic, social and economic statistics relating to Ballinamallard village and the surrounding townland communities of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy and Killadeas. According to the 1991 Census, 2439 persons resided in the Ballinamallard ward, comprising 1260 males and 1179 females; the population represents 4.5% of Fermanagh’s population and 0.15% of that of Northern Ireland. -

62953 Erne Waterway Chart

waterways chart_lower 30/3/04 3:26 pm Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 132 45678 GOLDEN RULES Lakeland Marine VORSICHT DRUMRUSH LODGE FOR CRUISING ON THE ERNE WATERWAY Niedrige Brücke. Durchfahrtshöhe 2.5M Use only long jetty H Teig Nur für kleine Boote MUCKROSS on west side of bay DANGER The Erne Waterway is not difficult to navigate, but there are some Golden Rules which MUST e’s R Harbour is too BE OBEYED AT ALL TIMES IF YOU ARE NOT TO RUN AGROUND or get into other trouble. Long Rock CAUTION shallow for cruisers Smith’s Rock ock Low bridge H.R 2.5m Fussweg H T KESH It must be appreciated that the Erne is a natural waterway and not dredged deep to the sides Small boats only Macart Is. Public footpath LOWER LOUGH ERNE like canal systems. In fact, the banks of the rivers and the shores of all the islands are normally P VERY SHALLOW a good way from the shore line and are quite often rocky! Bog Bay Fod Is. 350 H Rush Is. A47 Estea Island Pt. T Golden Rule No 1: NEVER CRUISE CLOSE TO THE SHORE (unless it is marked on the map Hare Island ross 5 LUSTY MORE uck that there is a good natural bank mooring). Keep more or less MID-STREAM wherever there A M Kesh River A 01234 Grebe WHITE CAIRN 8M are no markers, and give islands a very wide berth, at least 50-100 metres, unless there is a Black Bay BOA ISLAND 63C CAUTION Km x River mouth liable jetty on the island.