Implementation of Cooperative Education Programs. INSTITUTION Northeastern Univ., Boston, Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Offering Work-Integrated Learning Dual Study Programs

University offering work-integrated learning dual study programs AXEL GERLOFF1 Duale Hochschule Baden-Wuerttemberg Praesidium, Stuttgart, Germany KARIN REINHARD Duale Hochschule Baden-Wuerttemberg Ravensburg, Ravensburg, Germany ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ There is mutual agreement about the need for internationalization in higher education. However, there is no consensus regarding the best practice. Universities offering cooperative and work-integrated education have a comparative advantage in providing their graduates with capabilities needed on the labor market. They face the challenge to develop an internationalization strategy that reflects the practice-orientation of their study programs. The key question is how to use the specific feature of dual education to expand globally. This paper analyzes the approach of Duale Hochschule Baden-Wuerttemberg (DHBW) as Germany’s first university to integrate academic studies and work experience. It examines student exchanges, study-abroad internship tandems, short-term programs as well as the implementation of the DHBW model in other countries. The strengths and weaknesses of these approaches as well as their conformance with the objectives of the internationalization strategy are evaluated. Keywords: Dual education, employability, international collaboration, internationalization strategy The Duale Hochschule Baden-Wuerttemberg (DHBW) is the first university in Germany to integrate academic studies and practical experience. Almost 40 years ago, the model of the University was initiated by large German companies – among others Robert Bosch and Daimler-Benz. Its unique characteristics are the result of participation of training companies in the university and the integration of work experience in all study programs. A key question for developing DHBW’s internationalization strategy is how to use the specific feature of cooperative and work-integrated education to expand globally. -

Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering 1

Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering 1 BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN Robotics & Autonomous Systems – Circuit Technology Robotics & Autonomous Systems – Electrical Energy Systems ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING Robotics & Autonomous Systems – Bioengineering The School of Electrical and Computer Engineering offers two Robotics & Autonomous Systems – Sensing & Exploration undergraduate degree programs: Robotics & Autonomous Systems – Telecommunications • electrical engineering (EE) and • computer engineering (CmpE). Telecommunications – Electric Energy Systems Both programs include elective hours, enabling students to individually Telecommunications – Bioengineering tailor their programs to provide emphasis in a particular specialization or Telecommunications – Sensing & Exploration exposure to a broad range of subjects. Engineering analysis and design concepts are integrated throughout both programs, culminating in a Electronic Devices – Electric Energy Systems common major design experience involving a broad range of issues including economic and societal considerations. Electronic Devices – Circuit Technology The EE program offers elective courses in a wide variety of Electronic Devices – Bioengineering specializations including analog electronics, bioengineering, computer engineering, systems and controls, microsystems and nanosystems, Electronic Devices – Sensing & Exploration electronics packaging, digital signal processing, optics and photonics, Electronic Devices - Telecommunications electrical energy, electromagnetics, and telecommunications. -

2019 - 2020 Annual Report Year of Giant Leaps from the Director Table of Contents Eric A

2019 - 2020 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR OF GIANT LEAPS FROM THE DIRECTOR TABLE OF CONTENTS ERIC A. NAUMAN | DIRECTOR, OFFICE OF PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE 04 OUR PROGRAMS 06 2019 PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE EDUCATION HALL OF FAME 08 STUDENT AND EMPLOYER STATISTICS 10 STUDENT SPOTLIGHT - KILEY RODGERS 12 STUDENT SPOTLIGHT - TAKAYUKI MIYAUCHI 14 CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP 15 PARTNERS PROGRAM Greetings from the Office of Professional Practice (OPP)! 18 RESPONSE TO THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC I would like to start by thanking all of our corporate and academic partners for their 22 STUDENT SUCCESSES support in these challenging times and, as always, our alumni continue to provide encouragement and help sustain our efforts all around the world. The 2019-2020 24 PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE DONORS academic year was not at all what we expected, but our students continue to 25 SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENTS demonstrate their grit and work ethic. The OPP mission, to promote experiential education within the academic environment of the institution continues to be important to students, faculty, and our corporate partners and we are deeply appreciative of all our stakeholders. We continue to build our MILESTONES program and have pioneered a number of methods to provide students with hands-on experiences – even at a distance. It has been a considerable amount of effort, but this experience has offered our office opportunities for growth in how we collaborate and use technology. From an educational perspective, our goal is to ensure that Purdue students are able to accomplish as much as possible during their work rotations and expand their skill sets while on campus. Thank you for your interest in the Office of Professional Practice and all of Purdue’s Professional Practice Programs. -

University of Cooperative Education – Karlsruhe: the Dual System of Higher Education in Germany

e Asia- t d n u e c Pacific d a t u Co-op o Journal of t r s Education Cooperative employer Education Research Report University of Cooperative Education – Karlsruhe: The Dual System of Higher Education in Germany Axel Göhringer University of Cooperative Education-Karlsruhe Berufsakademie Karlsruhe, Erzbergerstr 121, 76133 Karlsruhe. Federal Republic of Germany Received 18 May 2002; accepted in revised form 30 August 2002 This paper describes the acceptance of German Berufsakademie or University of Cooperative Education graduates in the job market. This system, unique to this kind of university in Germany, combines theory and practice in equal parts. The first part of this paper describes this ‘dual’ system of education and provides a general overview of its history and the special features that make this model so effective in Germany. The second part of the paper describes the Berufsakademie Karlsruhe, its faculties and the importance of its location in one of Germany’s most advanced high-technology areas. The paper concludes with the presentation of some research findings for an empirical investigation, which shows that Berufsakademie graduates are highly sought after by their training companies and other employers. The research suggests that graduates are in demand because they are able to do responsible tasks soon after graduation without the need further training (Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(2), 53-58). Keywords: Germany; program description; technology; engineering; business; employer evaluation n the last two decades cooperative education at the Elektrik Lorenz (SEL) - an initiative was started to develop tertiary level has become increasingly important a system of dual education for secondary school graduates I worldwide. -

Dual Study Programmes: an Effective Symbiosis of Theory and Practice

Dual Study programmes: An effective symbiosis of theory and practice Wolfsburg und Baden- Württemberg, Germany 1 General Information Title Dual Study programmes – the hybrid higher educational programme Pitch Dual Study Programmes– an effective symbiosis of theory and practice Organisations VW Group, Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University (DHBW) Country Germany Authors Dr. Todd Davey and Balzhan Orazbayeva (Science-to-Business Marketing Re- search Centre) Nature of Collaboration in R&D Lifelong learning Commercialisation of R&D Joint curriculum design and interaction results delivery Mobility of staff Mobility of students Academic entrepreneurship Student entrepreneurship Governance Shared resources Supporting Strategic Structural mechanism Operational Policy Summary Dual study programmes are an emerging hybrid form of higher education, which offer the participant the opportunity to complete a degree programme at a higher education institution whilst simultaneously receiving a certifica- tion of practical vocational training or work experience in a company. In ad- dressing high youth unemployment as well as employability gaps, dual study programmes offer significant potential because they affectively close the gap between education and the world of work, resulting in better qualified and skills graduates, who might even emerge with a job already upon completion. With its origins in Germany, this case highlights dual study programmes from two perspectives: The HEI perspective through the example of Baden-Würt- temberg Cooperative State University and the VW Group from the business perspective 2 Introduction & Overview 1. BACKGROUND One of the policy recommendations of the ‘Modernisation Agenda of European Universities’ for higher education institutions is to involve employers, industry and labour market stakeholders in the design and delivery of programmes, and to make curricula include more on site practical compo- nents. -

University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering Kenneth P

University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences Engineering Technology, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown COOPERATIVE EDUCATION SPRING 2015 Co-op Notes and News You might be noticing a couple of new faces in the co-op office. LeeAnn Falcon joined our team as our Program Administrator back in September of 2014. LeeAnn has stepped in and has just been a tremendous help to our program and I am sure to all of you. LeeAnn previously spent several years working at Pitt but also has a background in events planning. So, for all of you who attended our wonderful dinner in December, you can thank LeeAnn for the beautiful touches. We also are enjoying the enthusiasm and Gian-Gabriel Garcia with Dean Gerald Holder professionalism of Pitt co-ops are again being Benedetta Khoury, our first graduate assistant from the recognized nationally! School of Education! Bene Benedetta Khoury and LeeAnn Falcon Gian-Gabriel Garcia, our Co-op Student works about 20 hours per week and we don’t know where we would be without of the Year, won the 2014 National her. If you are in need of a resume critique, mock interview, or even want a special Intern of the Year Award through the company called on your behalf, feel free to ask for Bene at the front desk. Cooperative and Experiential Education Division of the American Society of Our last fall term was quite a busy one! Our placements were up over 28% from Engineering Education. Gian was the fall of 2013. -

Expectation Towards Cooperative Education Management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan Thailand

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 103 ( 2013 ) 374 – 378 13th International Educational Technology Conference Expectation towards Cooperative Education Management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan Thailand Thanasarn SERMSUK* Department of Educational Technology, Faculty of Education, Kasetsart University, Thailand Abstract The purposes of this research were to find 1)the expectation of cooperative education management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan. 2)the opinion toward factor in cooperative education management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan. 3)the comparative analysis of cooperative education management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan by using qualitative research with technique EFR(Ethnographic Futures Research). The 20 samples consisted of educational institution group, enterprise group, Cooperative Education Associate group, parent group by purposive selection. The data collected by using semi-structured interview of expectation of cooperative education management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan by principle, concept and theory of attitudes, expectations and cooperative education management. The data was analyzed by using content analysis. The research findings revealed that : 1)the samples expect to the cooperative education system and believe that a good opportunities to use cooperative education system in educational management of Rajamangala University of Technology Isan, it is useful to create learning -

Kwantlen Polytechnic University

WE CAN'T WAIT TO HEAR FROM YOU KWANTLEN KPU International Drop in to see us Mailing Address Richmond, Main Building KPU International Surrey, Cedar Building Room 1145 12666 72 Avenue POLYTECHNIC Surrey, BC Canada, V3W 2M8 mykpu [email protected] @mykpu UNIVERSITY 1.604.599.2866 @mykpu METRO VANCOUVER, BC INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM GUIDE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS A PLACE TO THE KPU WAY COSTS & TERMS CALL HOME 11 KWANTLEN POLYTECHNIC 21 TUITION FEES & COST OF LIVING Welcome to KPU! We offer an unmatched range of sought-after What does it all cost? A message from our programs and it is our goal to be Canada’s leading polytechnic UNIVERSITY VALUES 03 A PLACE TO CALL HOME What's important to us at KPU. university. Find out why we're the best place on earth. 22 USEFUL TERMS President KPU is based in Metro Vancouver, widely regarded as one of the best places in the world to live, work and study. It is a safe and beautiful region, with many cultures living in harmony, and plenty to do on OUR PROGRAMS campus, in the cities, and on the surrounding sea shores and mountains. For over 30 years, KPU has taken pride in ensuring that our learners 23 PROGRAM LEGEND benefit from a vibrant campus and community life that inspires educators 04 WELCOME TO KPU and creates open and creative learning environments, dedicated to the OUR FACULTIES AND PROGRAMS success of our students. A sneak peek into KPU's programs 04 A POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY STUDENT We are committed to providing an enriched educational experience that Learn about traditional academic theory and SERVICES blends academic excellence with hands-on, experiential learning and career-focused, applied learning. -

Cooperative Higher Education: the Key to Success

COOPERATIVE HIGHER EDUCATION: THE KEY TO SUCCESS Experience the Advantage – the Synergy of Theory and Practice “ Having attained profound academic knowl edge and practical expertise, our graduates are best prepared to success fully start their professional careers.” Professor Reinhold R. Geilsdörfer, President of DHBW BADEN-WUERTTEMBERG COOPERATIVE STATE UNIVERSITY (DHBW) Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State Uni- ver sity is the first higher education institution in Germany to integrate academic studies with workplace training. Founded on March 1, 2009, DHBW traces its roots back to the Berufsakade- mie Baden-Wuerttemberg. Today the university continues to carry on the highly successful tradition of cooperative education. With over 34,000 students, about 9,000 corporate partner companies and social institutions and over 145,000 alumni, DHBW is the largest higher education institution in the German Federal State of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Throughout its 12 locations and campuses, DHBW offers a wide range of nationally and internationally accredited undergraduate study programmes in the field of business, engineering and social work. In addition, there is a great variety of postgraduate degree courses with an integrated on-the-job training as well as special programmes for non-degree seeking students. Become a fan on Facebook www.facebook.com/dhbw.home THE INNOVATIVE DUAL STUDY CONCEPT The core principle of the dual education at DHBW is the three-month rhythm, by which students switch between university and their workplace training provider aiming to offer both academic skills and work-related expertise. UNIQUE FEATURES OF WORK-INTEGRATED LEARNING DHBW closely cooperates with about 9,000 companies and social institutions all over Germany – its so-called corporate partners (Duale Partner in German). -

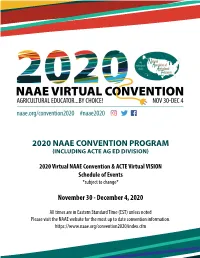

2020 Naae Convention Program (Including Acte Ag Ed Division)

2020 NAAE CONVENTION PROGRAM (INCLUDING ACTE AG ED DIVISION) 2020 Virtual NAAE Convention & ACTE Virtual VISION Schedule of Events *subject to change* November 30 - December 4, 2020 All times are in Eastern Standard Time (EST) unless noted Please visit the NAAE website for the most up to date convention information. https://www.naae.org/convention2020/index.cfm NAAE VIRTUAL CONVENTION NOVEMBER 30 - DECEMBER 4, 2020 NAAE VIRTUAL CONVENTION NOVEMBER 30 - DECEMBER 4, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR NAAE CONVENTION SPONSORS Committee Forums 4 Convention Schedule 4 Virtual Partners & Program Hall Participants 6 On-Demand Professional Development Sessions 7 NAAE Opening General Session I 12 NAAE General Session II 14 NAAE General Session III 15 Special thanks to Corteva AgriscienceTM for sponsoring the NAAE General Session IV 17 NAAE Agriscience Learning Labs at the 2020 NAAE Convention. NAAE General Session V 19 On-Demand Professional Development Session Descriptions 21 NAAE Board of Directors, Staff, and Contractors 30 Thanks to the National FFA Foundation for supporting NAAE and agricultural education. NAAE MISSION Special thanks to Lab-Aids for providing support “Professionals providing agricultural education for the global community for the NAAE Agriscience Learning Labs. through visionary leadership, advocacy and service.” 2 3 NAAE VIRTUAL CONVENTION NOVEMBER 30 - DECEMBER 4, 2020 NAAE VIRTUAL CONVENTION NOVEMBER 30 - DECEMBER 4, 2020 NAAE COMMITTEE DISCUSSION FORUMS MONDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2020 (TOOK PLACE PRIOR TO NAAE CONVENTION) 10:00 am-2:00 pm EST ACTE Pre-Session Workshops (additional fee & pre-registration required) Finance – Tuesday, November 17, 7:00 pm EST Visit www.acteonline.org for details. -

Cooperative Education in Agriculture Report

COOPERATIVE EDUCATION IN AGRICULTURE REPORT AT THE AGRONOMIC DEVELOPMENT SOUTHEAST ASIA FIELD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER OF BAYER CROPSCIENCE IN MASIIT, CALAUAN, LAGUNA, PHILIPPINES Miss PONSAWAN KHAMPHASAN ID. 543030378-3 INOCULATION METHODS AND MASS PRODUCTION OF DAMPING OFF CAUSED BY Pythium aphanidermatum, Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii IN LETTUCE AND ONION THIS REPORT IS PART OF THE COURSE 100495 COOPERATIVE EDUCATION IN AGRICULTURE BACHELOR OF SCIENCE AGRICULTURE (PLANT PATHOLOGY) FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE KHON KEAN UNIVERSITY JULY 2014 COOPERATIVE EDUCATION IN AGRICULTURE REPORT Academic year 2013 Title : Inoculation methods and mass production of damping-off caused by Pythium aphanidermatum, Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii in lettuce and onion at the Bayer Cropscience (AD-SEA) in the Philippines Name of reporter: Miss Ponsawan Khamphasan Name of company: The Agronomic Development Southeast Asia Field Research and Development Center of Bayer CropScience (AD-SEA) Address: Bayer CropScience, Inc., Agronomic Development Southeast Asia Field Research and Development Center (ADSEA), Barangay Masiit, Calauan, Laguna, Philippines Job supervisors: Mr. Leo Hawod Position: Lead Researcher (Disease Management) ……………………………………………………………………Adviser (Dr. Anan Wongcharone) Board of Cooperative Education …………………………………………………………………… committee (Dr. Anan Wongcharone) …………………………………………………………………… committee (………………………………………………………………..) Copyright of faculty of agriculture Khon kaen university COOPERATIVE EDUCATION IN AGRICULTURE REPORT The Bayer CropScience Agronomic Development Southeast Asia Field Research and Development Center (AD-SED) at Masiit, Calauan, Laguna, Philippines Miss Ponsawan Khamphasan ID. 543030378-3 This report is part of the course 100495 cooperative education in agriculture Bachelor of science agriculture (Plant pathology) Faculty of agriculture Khon kaen university July 2014 a Acknowledgements In performing my internship, it's a successful one I had to take the help and guideline of some respected persons. -

Learning Outcomes Achievement in Cooperative Education: a Survey of Engineering Students

AC 2010-1524: LEARNING OUTCOMES ACHIEVEMENT IN COOPERATIVE EDUCATION: A SURVEY OF ENGINEERING STUDENTS Jennifer Johrendt, University of Windsor Dr. Johrendt obtained her doctorate in Mechanical Engineering in 2005 from the University of Windsor after working for almost ten years as a Product Development Engineer in the automotive industry. Currently an Assistant Professor of Mechanical and Automotive Engineering at the University of Windsor, she previously worked for two years as an Experiential Learning Specialist in the department. She serves as both the Faculty and Departmental Cooperative Education representative. She has co-authored several journal paper publications and conference presentations that have featured experiential learning and engineering education topics as well as her engineering research in vehicle structural durability and the use of neural networks to model non-linear material behaviour. Schantal Hector, University of Windsor Ms. Hector is currently pursuing her Bachelor's Degree in International Relations and Economics at the University of Windsor. She is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Career Education and has applied her knowledge and skills as part of the project to develop learning outcomes for the cooperative education program over the past two years. She has been instrumental in the collection and statistical analysis of the learning outcomes data using Excel and SPSS methods and its presentation into a comprehensible graphic format. Other endeavours have included aiding in the development of an online course for co-op students at the University of Windsor and engaging in research that seeks to enhance the employment options for graduates. Her research interest continues to be to help enrich and enhance the co-op experience for other students.