Winning the War: the Memory and Reality of the Ira in West Cork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

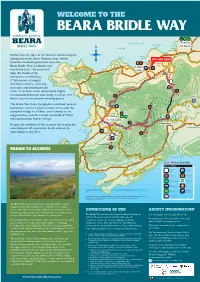

BEARA BRIDLEWAY A1 MAP Urhan

WELCOME TO THE BEARA BRIDLE WAY KENMARE BAY Eyeries Ardacluggin Pallas Point Na haoraí Carrigeel Strand Etched into the sides of the Miskish and Knockgour Travara Rahis Pt mountains of the Slieve Miskish range which Strand YOU ARE HERE knuckles the Beara peninsula west, the Urhan Urhan Beara Bridle Way is Ireland’s first Travaud Urhan Inn Valley ever horse trail. The main trail Gortahig Iorthan hugs the flanks of the Caherkeen mountains, overlooking 90m 17 kilometres of rugged mountain scenery, stunning y seascapes and dazzling island le Wa a Brid ar views. It includes some optional but highly Be recommended detours that climb to access even 230m Trekking better vistas from elevated viewing points. 220m Knockoura Centre 490m The Bridle Way links Clonglaskin townland several kilometres west of Castletownbere town with the Knockgour colourful village of Allihies, once famous for its 400m Teernahilane coppermines, and the coastal townland of Urhan Allihies near picturesque Eyeries village. Na hAilichí 320m 90m Despite the wildness of the scenery, the terrain has 70m Clonglaskin something for all experience levels and can be Beach To Castletownbere Ballydonegan View B&B undertaken at any pace. Beach Holiday Homes Gour 330m R575 Foher Cahermeeleboe 190m URHAN TO ALLIHIES R575 Bealbarnish Gap BANTRY BAY Beara Bridle Way KEY TO SYMBOLS Bridleway Parking Gates View Point Restaurant Accommodation Swimming B&B for Horses Bar Drinking water Post Office for horses Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2016/06/CCMA/CorkCountyCouncil Trekking Centre Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, 2016 The Bridle Way follows an old road originally built to enable villagers from Urhan and Eyeries to commute to the Allihies mines. -

The Welfare of Irish Political Prisoners in Dundalk Gaol in the Aftermath of Thomas Ashe’S Death, Oct 1917 - Jul 1918 Ailbhe Rogers

The welfare of Irish political prisoners in Dundalk Gaol in the aftermath of Thomas Ashe’s death, Oct 1917 - Jul 1918 Ailbhe Rogers Women praying outside Mountjoy Prison for Kevin Barry, 1920 (National Library of Ireland) Dundalk Gaol (National Library of Ireland) Background: Various political prisoner autographs from Inside B Wing of Dundalk Gaol (Louth County Council) Dundalk Gaol 1917-18 (Kilmainham Gaol Archives) Matthews family pictured with Mrs. Margaret Pearse (Military Archives) Dundalk Cumann na mBan posing with bandoliers, rifles and cigarettes (Private possession) Dundalk Gaol autograph book (Kilmainham Gaol Museum) Advert for Carroll’s Silk Cut cigarettes (Nationality, 1917) Patriotic Christmas card (Military Archives) Dundalk Gaol, 1918. Back Row (L-R): Diarmuid Lynch, Ernest Blythe, Terence MacSwiney, Dick McKee, Michael Colivet Front Row (L-R): Frank Thornton, Bertie Hunt, Michael Brennan (Kilmainham Gaol Archives/Military Archives) Máire, Muriel and Terence MacSwiney (Cork Public Museum) Kathleen and Diarmuid Lynch (Lynch Family Archive) Taken from inside a Dundalk Gaol cell, 1918 (L-R) Frank Thornton, Joseph Berrill, Patrick J. Flynn, James Toal (Kilmainham gaol Archives) ‘I wish to convey to yourself and the Dundalk people.. our thanks for their efforts on our behalf. Certainly ye went to an enormous amount of trouble and we.. can never forget it.. Be sure you convey to them my deepest gratitude.’ – Austin Stack, Tralee, 1917. ‘Thank you very much for your kindness to the boys as we have heard what good the Cumann na mBan of Dundalk has done for the prisoners.’ – Éilis Ryan, INAVDF, Dublin, 1918 ‘I have been ordered to extend our gratitude to you all for the eggs you brought us in honour of Easter Sunday. -

Intermarriage and Other Families This Page Shows the Interconnection

Intermarriage and Other Families This page shows the interconnection between the Townsend/Townshend family and some of the thirty-five families with whom there were several marriages between 1700 and 1900. It also gives a brief historical background about those families. Names shown in italics indicate that the family shown is connected with the Townsend/Townshend elsewhere. Baldwin The Baldwin family in Co Cork traces its origins to William Baldwin who was a ranger in the royal forests in Shropshire. He married Elinor, daughter of Sir Edward Herbert of Powys and went to Ireland in the late 16th century. His two sons settled in the Bandon area; the eldest brother, Walter, acquired land at Curravordy (Mount Pleasant) and Garrancoonig (Mossgrove) and the youngest, Thomas, purchased land at Lisnagat (Lissarda) adjacent to Curravordy. Walter’s son, also called Walter, was a Cromwellian soldier and it is through his son Herbert that the Baldwin family in Co Cork derives. Colonel Richard Townesend [100] Herbert Baldwin b. 1618 d. 1692 of Curravordy Hildegardis Hyde m. 1670 d. 1696 Mary Kingston Marie Newce Horatio Townsend [104] Colonel Bryan Townsend [200] Henry Baldwin Elizabeth Becher m. b. 1648 d. 1726 of Mossgrove 1697 Mary Synge m. 13 May 1682 b. 1666 d. 1750 Philip French = Penelope Townsend [119] Joanna Field m. 1695 m. 1713 b. 1697 Elizabeth French = William Baldwin John Townsend [300] Samuel Townsend [400] Henry Baldwin m. 1734 of Mossgrove b. 1691 d. 1756 b.1692 d. 1759 of Curravordy b.1701 d. 1743 Katherine Barry Dorothea Mansel m. 1725 b. 1701 d. -

Whats on CORK

Festivals CORK CITY & COUNTY 2019 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE January 5 to 18 Mental Health First Fortnight Various Venues Cork City & County www.firstfortnight.ie January 11 to 13 Chess Mulcahy Memorial Chess Metropole Hotel Cork Congress www.corkchess.com January 12 to 13 Tattoo Winter Tattoo Bash Midleton Park Hotel www.midletontattooshow.ie January 23 to 27 Music The White Horse Winter The White Horse Ballincollig Music Festival www.whitehorse.ie January TBC Bluegrass Heart & Home, Old Time, Ballydehob Good Time & Bluegrass www.ballydehob.ie January TBC Blues Murphy’s January Blues Various Locations Cork City Festival www.soberlane.com Jan/Feb 27 Jan Theatre Blackwater Valley Fit Up The Mall Arts Centre Youghal 3,10,17 Feb Theatre Festival www.themallartscentre.com Jan/Feb 28 to Feb 3 Burgers Cork Burger Festival Various Venues Cork City & County www.festivalscork.com/cork- burger-festival Jan/Feb 31 to Feb 2 Brewing Cask Ales & Strange Franciscan Well North Mall Brew Festival www.franciscanwell.com February 8 to 10 Arts Quarter Block Party North & South Main St Cork www.makeshiftensemble.com February TBC Traditional Music UCC TadSoc Tradfest Various Venues www.tradsoc.com February TBC Games Clonakilty International Clonakilty Games Festival www.clonakiltygamesfestival.co m February Poetry Cork International Poetry Various Venues Festival www.corkpoetryfest.net Disclaimer: The events listed are subject to change please contact the venue for further details | PAGE 1 OF 11 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE Feb/Mar -

Audit Maritime Collections 2006 709Kb

AN THE CHOMHAIRLE HERITAGE OIDHREACHTA COUNCIL A UDIT OF M ARITIME C OLLECTIONS A Report for the Heritage Council By Darina Tully All rights reserved. Published by the Heritage Council October 2006 Photographs courtesy of The National Maritime Museum, Dunlaoghaire Darina Tully ISSN 1393 – 6808 The Heritage Council of Ireland Series ISBN: 1 901137 89 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Objective 4 1.2 Scope 4 1.3 Extent 4 1.4 Methodology 4 1.5 Area covered by the audit 5 2. COLLECTIONS 6 Table 1: Breakdown of collections by county 6 Table 2: Type of repository 6 Table 3: Breakdown of collections by repository type 7 Table 4: Categories of interest / activity 7 Table 5: Breakdown of collections by category 8 Table 6: Types of artefact 9 Table 7: Breakdown of collections by type of artefact 9 3. LEGISLATION ISSUES 10 4. RECOMMENDATIONS 10 4.1 A maritime museum 10 4.2 Storage for historical boats and traditional craft 11 4.3 A register of traditional boat builders 11 4.4 A shipwreck interpretative centre 11 4.5 Record of vernacular craft 11 4.6 Historic boat register 12 4.7 Floating exhibitions 12 5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 12 5.1 Sources for further consultation 12 6. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF RECORDED COLLECTIONS 13 7. MARITIME AUDIT – ALL ENTRIES 18 1. INTRODUCTION This Audit of Maritime Collections was commissioned by The Heritage Council in July 2005 with the aim of assisting the conservation of Ireland’s boating heritage in both the maritime and inland waterway communities. 1.1 Objective The objective of the audit was to ascertain the following: -

Michael Davitt 1846 – 1906

MICHAEL DAVITT 1846 – 1906 An exhibition to honour the centenary of his death MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY www.mayolibrary.ie MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY MICHAEL DAVITTwas born the www.mayolibrary.ie son of a small tenant farmer at Straide, Co. Mayo in 1846. He arrived in the world at a time when Ireland was undergoing the greatest social and humanitarian disaster in its modern history, the Great Famine of 1845-49. Over the five or so years it endured, about a million people died and another million emigrated. BIRTH OF A RADICAL IRISHMAN He was also born in a region where the Famine, caused by potato blight, took its greatest toll in human life and misery. Much of the land available for cultivation in Co. Mayo was poor and the average valuation of its agricultural holdings was the lowest in the country. At first the Davitts managed to survive the famine when Michael’s father, Martin, became an overseer of road construction on a famine relief scheme. However, in 1850, unable to pay the rent arrears for the small landholding of about seven acres, the family was evicted. left: The enormous upheaval of the The Famine in Ireland — Extreme pressure of population on Great Famine that Davitt Funeral at Skibbereen (Illustrated London News, natural resources and extreme experienced as an infant set the January 30, 1847) dependence on the potato for mould for his moral and political above: survival explain why Mayo suffered attitudes as an adult. Departure for the “Viceroy” a greater human loss (29%) during steamer from the docks at Galway. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 13 NOVEMBER, 1946 5593 So That They Could Take Their Place Jn a British Indiscipline in Both Brigades

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13 NOVEMBER, 1946 5593 so that they could take their place Jn a British indiscipline in both brigades. The instigators field force. of the disturbances were left-wing officers and 258. The 2nd Polish Corps, under command men with violent anti-Metaxist sympathies. It of General Anders, was the largest allied force became necessary to remove a number of to 'be trained and equipped in this manner. officers, but for political reasons the ringleaders In August, 1943, a Polish Corps of two infantry could not be removed. The formation of the divisions and one tank brigade began to move ist Greek Divisional Headquarters was discon- to Middle East from Persia and Iraq Command. tinued and the command of both brigades was By the middle of October the first part of the taken over temporarily by British Brigadiers. move was complete, and most of the corps was On. 6th July further disturbances took place, concentrated for training in Southern Palestine. this time mainly 'in the 2nd Greek Brigade, At the end of November the corps moved to as a result of which two battalions of the 2nd Egypt, preparatory to moving overseas to Brigade were disbanded, and .the ist Italy. Here re-organisation took place on the Brigade wasi completed to war establishment latest British war establishments, to bring the tfrom the reliable elements of the 2nd Brigade. corps into' line with British formations and The 8th Greek Battalion, which was intended units, and on loth December the move to Italy for guard duties only, was formed from the began. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

Towns Across Cork County Including Cobh Develop Ideas for Their Future Vision

Towns across Cork County including Cobh develop ideas for their future vision HOME LOCAL NEWS SPORT ANNOUNCEMENTS EVENTS & ENTERTAINMENT USEFUL COBH NUMBERS COMMUNITY COBH GUIDE CONTACT US LOCAL NEWS LATEST POPULAR LOCAL NEWS / 55 mins ago Towns across Cork County including Cobh CORK’S BALLYMALOE FOODS SCOOP develop ideas for their future vision MAJOR FOOD AWARDS ANNOUNCEMENTS / 2 days ago Published 4 days ago on September 18, 2020 JOB OPPORTUNITIES: Commodore By admin Hotel, Cobh LOCAL NEWS / 4 days ago Towns across Cork County including Cobh develop ideas for their future vision SPORT / 4 days ago Preview: Athlone Town v Cobh Ramblers LOCAL NEWS / 5 days ago Port of Cork Company Appoints New Chief Executive Eight towns across Cork County have been developing exciting new visions for their respective towns as part of the My Town, My Plan Community Training Programme. Community representatives from Carrigaline, Cobh, Clonakilty, Kinsale, Midleton, Rosscarbery, Skibbereen and Youghal committed to several months engagement and participation to collaborate and develop new ideas. LATEST LOCAL WEATHER The Hincks Centre for Entrepreneurship Excellence, part of the School of Business at Cork Institute of Technology (CIT) designed and delivered the programme and funded Cobh Weather through SECAD Partnership CLG. The face-to-face training and consultative sessions by TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY expert facilitators began last September and as Covid-19 hit in mid-March, the April and May sessions moved online. The programme comprised of 4 core topics, delivered by experts, on developing community projects/enterprises, moving from ideas to validation, legal 18° 11° 14° 8° 13° 8° structures/governance and strategic planning and were delivered in each town over 8 evening sessions. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History, 1913-21

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 604 Witness patrick Fehily, High Street, Skibbereen, Co. Cork. Identity. Officer Commanding Skibbereen Company (4th Battalion) Cork Brigade. Subject. His national activities, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No S.1884 Form B.S.M.2 PATRICK FEHILY, HIGH STREET, SKIBBEREEN O.C. SKIBBEREEN COMPANY, 4TH BATTALION, CORK III BRIGADE I took part in the collecting and raiding for arms as well as collecting for the Arms Fund. I was running despatches for Tadgh O'Sullivan, first Company Commanding Officer in Skibbereen, before I was in the Volunteers at all I took part in the burning of the Courthouse in the early Summer of 1921. There. was an ambush at Goggin's corner in the town on a Saturday night and six of us attacked 14 (fourteen) armed R.I.C. This was in June, 1921. We had 2 (two) rifles and 3 (three) shot-guns and a few revolvers It was a pitched battle while it lasted and the R.I.C. at length ran for the Barracks. Most of them were regular R.I.C. with a few Tans. They may have had casualties, though not that we could see. They left no arms for us to collect. The six of us left the town afterwards and came back quietly the following evening and we were not suspected. I was sworn into the I.R.B. at the same time as Stephen O'Brien, the Battalion Adjutant, that is about six weeks before the Truce.