Assessing Smes and Mini-Bond Issuers Creditworthiness FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle

The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle Matthias Fleckenstein, Francis A. Longstaff and Hanno Lustig The Journal of Finance, October 2014 Presented By: Rafael A. Porsani The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle 1 / 55 Introduction The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle 2 / 55 Introduction (1) Treasury bond and the Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) markets: two of the largest and most actively traded fixed-income markets in the world. Find that there is persistent mispricing on a massive scale across them. Treasury bonds are consistently overpriced relative to TIPS. Price of a Treasury bond can exceed that of an inflation-swapped TIPS issue exactly matching the cash flows of the Treasury bond by more than $20 per $100 notional amount. One of the largest examples of arbitrage ever documented. The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle 3 / 55 Introduction (2) Use TIPS plus inflation swaps to create synthetic Treasury bond. Price differences between the synthetic Treasury bond and the nominal Treasury bond: arbitrage opportunities. Average size of the mispricing: 54.5 basis points, but can exceed 200 basis points for some pairs. I The average size of this mispricing is orders of magnitude larger than transaction costs. The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle 4 / 55 Introduction (3) What drives the mispricing? Slow-moving capital may help explain why mispricing persists. Is TIPS-Treasury mispricing related to changes in capital available to hedge funds? Answer: Yes. Mispricing gets smaller as more capital gets to the hedge fund sector. The TIPS-Treasury Bond Puzzle 5 / 55 Introduction (4) Also find that: Correlation in arbitrage strategies: size of TIPS-Treasury arbitrage is correlated with arbitrage mispricing in other markets. -

3. VALUATION of BONDS and STOCK Investors Corporation

3. VALUATION OF BONDS AND STOCK Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Understand the role of stocks and bonds in the financial markets. 2. Calculate value of a bond and a share of stock using proper formulas. 3.1 Acquisition of Capital Corporations, big and small, need capital to do their business. The investors provide the capital to a corporation. A company may need a new factory to manufacture its products, or an airline a few more planes to expand into new territory. The firm acquires the money needed to build the factory or to buy the new planes from investors. The investors, of course, want a return on their investment. Therefore, we may visualize the relationship between the corporation and the investors as follows: Capital Investors Corporation Return on investment Fig. 3.1: The relationship between the investors and a corporation. Capital comes in two forms: debt capital and equity capital. To raise debt capital the companies sell bonds to the public, and to raise equity capital the corporation sells the stock of the company. Both stock and bonds are financial instruments and they have a certain intrinsic value. Instead of selling directly to the public, a corporation usually sells its stock and bonds through an intermediary. An investment bank acts as an agent between the corporation and the public. Also known as underwriters, they raise the capital for a firm and charge a fee for their services. The underwriters may sell $100 million worth of bonds to the public, but deliver only $95 million to the issuing corporation. -

Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry*

Learning Curve September 2005 Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry* © YieldCurve.com 2005 A key measure of relative value of a corporate bond is its swap spread. This is the basis point spread over the interest-rate swap curve, and is a measure of the credit risk of the bond. In its simplest form, the swap spread can be measured as the difference between the yield-to-maturity of the bond and the interest rate given by a straight-line interpolation of the swap curve. In practice traders use the asset-swap spread and the Z- spread as the main measures of relative value. The government bond spread is also considered. We consider the two main spread measures in this paper. Asset-swap spread An asset swap is a package that combines an interest-rate swap with a cash bond, the effect of the combined package being to transform the interest-rate basis of the bond. Typically, a fixed-rate bond will be combined with an interest-rate swap in which the bond holder pays fixed coupon and received floating coupon. The floating-coupon will be a spread over Libor (see Choudhry et al 2001). This spread is the asset-swap spread and is a function of the credit risk of the bond over and above interbank credit risk.1 Asset swaps may be transacted at par or at the bond’s market price, usually par. This means that the asset swap value is made up of the difference between the bond’s market price and par, as well as the difference between the bond coupon and the swap fixed rate. -

Evidence from SME Bond Markets

Temi di discussione (Working Papers) Asymmetric information in corporate lending: evidence from SME bond markets by Alessandra Iannamorelli, Stefano Nobili, Antonio Scalia and Luana Zaccaria September 2020 September Number 1292 Temi di discussione (Working Papers) Asymmetric information in corporate lending: evidence from SME bond markets by Alessandra Iannamorelli, Stefano Nobili, Antonio Scalia and Luana Zaccaria Number 1292 - September 2020 The papers published in the Temi di discussione series describe preliminary results and are made available to the public to encourage discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors and do not involve the responsibility of the Bank. Editorial Board: Federico Cingano, Marianna Riggi, Monica Andini, Audinga Baltrunaite, Marco Bottone, Davide Delle Monache, Sara Formai, Francesco Franceschi, Salvatore Lo Bello, Juho Taneli Makinen, Luca Metelli, Mario Pietrunti, Marco Savegnago. Editorial Assistants: Alessandra Giammarco, Roberto Marano. ISSN 1594-7939 (print) ISSN 2281-3950 (online) Printed by the Printing and Publishing Division of the Bank of Italy ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION IN CORPORATE LENDING: EVIDENCE FROM SME BOND MARKETS by Alessandra Iannamorelli†, Stefano Nobili†, Antonio Scalia† and Luana Zaccaria‡ Abstract Using a comprehensive dataset of Italian SMEs, we find that differences between private and public information on creditworthiness affect firms’ decisions to issue debt securities. Surprisingly, our evidence supports positive (rather than adverse) selection. Holding public information constant, firms with better private fundamentals are more likely to access bond markets. Additionally, credit conditions improve for issuers following the bond placement, compared with a matched sample of non-issuers. These results are consistent with a model where banks offer more flexibility than markets during financial distress and firms may use market lending to signal credit quality to outside stakeholders. -

Bond Liquidity and Dealer Inventories: Insights from US and European Regulatory Data

52 Financial Conduct Authority Occasional Paper Securities and Exchange Commission DERA Working Paper February 2020 Bond liquidity and dealer inventories: Insights from US and European regulatory data Plamen Ivanov, Alexei Orlov and Michael Schihl Occasional Paper 52 / DERA Working Paper Bond liquidity and dealer inventories Occasional Paper 52 / DERA Working Paper Abstract Most corporate bond research on liquidity and dealer inventories is based on the USD- denominated bonds transactions in the US reported to TRACE. Some of these bonds, however, are also traded in Europe, and those trades are not subject to the TRACE reporting require- ments. Leveraging our access to both TRACE and ZEN, the UK's trade reporting system which is not publicly available, we find an overlap of about 30,000 bonds that are traded both in the US and in Europe. This paper examines how using the CUSIP-level information from TRACE and ZEN affects the computation of bond liquidity metrics, dealer inventories, and the relationship between the two. We find that in the combined dataset, the weekly volume traded and number of trades are significantly higher than in TRACE: e.g., the average unconditional number of trades in investment-grade (high-yield) bonds is 17% (20%) higher and the average uncondi- tional volume traded is 15% (17%) higher when we incorporate the information from ZEN. We find a strong positive relationship between inventories and liquidity, as proxied by the trading activity metrics (i.e., number of trades, zero trading days, or par value traded) in TRACE data, and this result carries over to the combined dataset. -

Mortgage-Backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations

Mortgage-backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Prudent CRA INVESTMENT Opportunities by Andrew Kelman,Director, National Business Development M Securities Sales and Trading Group, Freddie Mac Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) have Here is how MBSs work. Lenders because of their stronger guarantees, become a popular vehicle for finan- originate mortgages and provide better liquidity and more favorable cial institutions looking for investment groups of similar mortgage loans to capital treatment. Accordingly, this opportunities in their communities. organizations like Freddie Mac and article will focus on agency MBSs. CRA officers and bank investment of- Fannie Mae, which then securitize The agency MBS issuer or servicer ficers appreciate the return and safety them. Originators use the cash they collects monthly payments from that MBSs provide and they are widely receive to provide additional mort- homeowners and “passes through” the available compared to other qualified gages in their communities. The re- principal and interest to investors. investments. sulting MBSs carry a guarantee of Thus, these pools are known as mort- Mortgage securities play a crucial timely payment of principal and inter- gage pass-throughs or participation role in housing finance in the U.S., est to the investor and are further certificates (PCs). Most MBSs are making financing available to home backed by the mortgaged properties backed by 30-year fixed-rate mort- buyers at lower costs and ensuring that themselves. Ginnie Mae securities are gages, but they can also be backed by funds are available throughout the backed by the full faith and credit of shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages or country. The MBS market is enormous the U.S. -

Corporate Bonds and Debentures

Corporate Bonds and Debentures FCS Vinita Nair Vinod Kothari Company Kolkata: New Delhi: Mumbai: 1006-1009, Krishna A-467, First Floor, 403-406, Shreyas Chambers 224 AJC Bose Road Defence Colony, 175, D N Road, Fort Kolkata – 700 017 New Delhi-110024 Mumbai Phone: 033 2281 3742/7715 Phone: 011 41315340 Phone: 022 2261 4021/ 6237 0959 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.vinodkothari.com 1 Copyright & Disclaimer . This presentation is only for academic purposes; this is not intended to be a professional advice or opinion. Anyone relying on this does so at one’s own discretion. Please do consult your professional consultant for any matter covered by this presentation. The contents of the presentation are intended solely for the use of the client to whom the same is marked by us. No circulation, publication, or unauthorised use of the presentation in any form is allowed, except with our prior written permission. No part of this presentation is intended to be solicitation of professional assignment. 2 About Us Vinod Kothari and Company, company secretaries, is a firm with over 30 years of vintage Based out of Kolkata, New Delhi & Mumbai We are a team of qualified company secretaries, chartered accountants, lawyers and managers. Our Organization’s Credo: Focus on capabilities; opportunities follow 3 Law & Practice relating to Corporate Bonds & Debentures 4 The book can be ordered by clicking here Outline . Introduction to Debentures . State of Indian Bond Market . Comparison of debentures with other forms of borrowings/securities . Types of Debentures . Modes of Issuance & Regulatory Framework . -

Corporate Bond Market Dysfunction During COVID-19 and Lessons

Hutchins Center Working Paper # 69 O c t o b e r 2 0 2 0 Corporate Bond Market Dysfunction During COVID-19 and Lessons from the Fed’s Response J. Nellie Liang* October 1, 2020 Abstract: Changes in the financial sector since the global financial crisis appear to have increased dramatically the demand for liquidity by holders of corporate bonds beyond the ability of the markets to provide it in stress events. The March market turmoil revealed the costs of liquidity mismatch in open-end bond mutual funds. The surprisingly large redemptions of investment-grade corporate bond funds added to stresses in both the corporate bond and Treasury markets. These conditions led to unprecedented Fed interventions, which significantly reduced risk spreads and improved market functioning, with much of the improvements occurring right after the initial announcement. The improved conditions allowed companies to issue bonds, which helped them to maintain employees and investment spending. The episode suggests several areas for further study and possible reforms. * J. Nellie Liang, Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, Brookings Institution ([email protected]). I would like to thank Darrell Duffie, Bill English, Anil Kashyap, Donald Kohn, Patrick Parkinson, Jeremy Stein, Adi Sunderam, David Wessel, and Alex Zhou for helpful comments and insights, and Manuel Alcalá Kovalski for excellent research assistance. THIS PAPER IS ONLINE AT https://www.brookings.edu/research/corporate- bond-market-dysfunction-during-covid-19-and- lessons-from-the-feds-response/ 1. Introduction As concerns about the pandemic’s effect on economic activity in early March escalated, asset prices began to move in unusual ways—including the prices of investment-grade corporate bonds. -

The Use of Credit Default Swaps by U.S. Fixed-Income Mutual Funds

Sanjiv R. Das FDIC Center for Financial Research Darrell Duffie Working Paper Nikunj Kapadia No. 2011-01 Empirical Comparisons and Implied Recovery Rates The Use of Credit Default Swaps by U.S Fixed-Income Mutual Funds Risk-Based Capital Standards, kkk Deposit Insurance and Procyclicality November 19, 2010 Risk-Based Capital Standards, Deposit Insurance and Procyclicality An Empirical September 2005 An Empirical Analysis Federal Dposit Insurance Corporation •Center for Financial Researchh State- May, 2005 Efraim Benmel Efraim Benmelech June 20 May , 2005 Asset S2005-14 The Use of Credit Default Swaps by U.S. Fixed-Income Mutual Funds Tim Adam, Humboldt University* and Risk Management Institute (Singapore) Andre Guettler, University of Texas at Austin and EBS Business School† November 19, 2010 Abstract We examine the use of credit default swaps (CDS) in the U.S. mutual fund industry. We find that among the largest 100 corporate bond funds the use of CDS has increased from 20% in 2004 to 60% in 2008. Among CDS users, the average size of CDS positions (measured by their notional values) increased from 2% to almost 14% of a fund’s net asset value. Some funds exceed this level by a wide margin. CDS are predominantly used to increase a fund’s exposure to credit risks rather than to hedge credit risk. Consistent with fund tournaments, underperforming funds use multi-name CDS to increase their credit risk exposures. Finally, funds that use CDS underperform funds that do not use CDS. Part of this underperformance is caused by poor market timing. JEL-Classification: G11, G15, G23 Keywords: Corporate bond fund, credit default swap, credit risk, fund performance, hedging, speculation, tournaments * Humboldt University, Institute of Corporate Finance, Dorotheenstr. -

Nber Working Paper Series Facts and Fantasies About

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FACTS AND FANTASIES ABOUT COMMODITY FUTURES TEN YEARS LATER Geetesh Bhardwaj Gary Gorton Geert Rouwenhorst Working Paper 21243 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21243 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2015 The paper has benefited from comments by seminar participants at the 2015 Bloomberg Global Commodity Investment Roundtable, the 2015 FTSE World Investment Forum, and from Rajkumar Janardanan, Kurt Nelson, Ashraf Rizvi, and Matthew Schwab. Gorton has nothing to currently disclose. He was a consultant to AIG Financial Products from 1996-2008. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21243.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Geetesh Bhardwaj, Gary Gorton, and Geert Rouwenhorst. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures Ten Years Later Geetesh Bhardwaj, Gary Gorton, and Geert Rouwenhorst NBER Working Paper No. 21243 June 2015 JEL No. G1,G11,G12 ABSTRACT Gorton and Rouwenhorst (2006) examined commodity futures returns over the period July 1959 to December 2004 based on an equally-weighted index. -

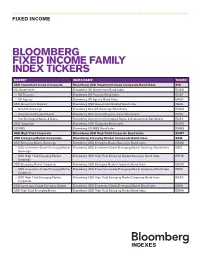

Bloomberg Fixed Income Family Index Tickers

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// FIXED INCOME BLOOMBERG FIXED INCOME FAMILY INDEX TICKERS MARKET INDEX NAME TICKER USD Investment Grade Composite Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Composite Bond Index BIG US Government Bloomberg US Government Bond Index BUSG » US Treasury Bloomberg US Treasury Bond Index BUSY » US Agency Bloomberg US Agency Bond Index BAGY USD Government Related Bloomberg USD Government Related Bond Index BGRL » Non-US Sovereign Bloomberg Non-US Sovereign Bond Index BNSO » Government Regional/Local Bloomberg Government Regional/Local Bond Index BRGL » Gov Developed Banks & Supra Bloomberg Government Developed Banks & Supranational Bond Index BDEV USD Corporate Bloomberg USD Corporate Bond Index BUSC US MBS Bloomberg US MBS Bond Index BMBS USD High Yield Corporate Bloomberg USD High Yield Corporate Bond Index BUHY USD Emerging Market Composite Bloomberg Emerging Market Composite Bond Index BEM USD Emerging Market Sovereign Bloomberg USD Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEMS » USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEIS Sovereign » USD High Yield Emerging Market Bloomberg USD High Yield Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEHS Sovereign USD Emerging Market Corporate Bloomberg USD Emerging Market Corporate Bond Index BEMC » USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Corporate Bond Index BIEM Corporate -

Default & Returns on High Yield Corporate Bonds

Soluzioni Innovative: (Private) & Public Debt Crediamo nella supremazia della Conoscenza. Dr. Edward Altman Crediamo nelle forza delle Idee. Co-Founder & Senior Advisor Classis Capital Sim SpA Crediamo nell’Ispirazione. 1 Turin, April 12, 2017 Agenda . Current Conditions and Outlook in Global Credit Markets . Assessing the Credit Health of the Italian SME Sector . Minibond Issuers 2 Major Agencies Bond Rating Categories Moody's S&P/Fitch Aaa AAA Aa1 AA+ Aa2 AA Aa3 AA- A1 A+ A2 A A3 A- Baa1 BBB+ Baa2 Investment BBB Baa3 Grade BBB- Ba1 High Yield BB+ Ba2 ("Junk") BB Ba3 BB- B1 B+ B2 B B3 B- High Yield Caa1 CCC+ Market Caa CCC Caa3 CCC- Ca CC C C D 3 Size Of High-Yield Bond Market 1978 – 2017 (Mid-year US$ billions) $1.800 $1,624 $1.600 Source: NYU $1.400 Salomon Center $1.200 estimates US Market using Credit $1.000 Suisse, S&P $800 and Citi data $ (Billions)$ $600 $400 $200 $- 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 1994 – 2016 (Mid-year € billions)* 500 468€ 471 Western Europe Market 418 400 370 ) 300 283 Source: Credit 200 194 Suisse Billions ( 154 € 108 100 81 61 70 89 84 81 79 80 77 0 2 5 9 14 27 45 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 *Includes non-investment grade straight corporate debt of issuers with assets located in or revenues derived from Western Europe, or the bond is denominated in a Western European currency.