(2012) Reliability Examination in Horizontal-Merger Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MK ITEM / INTERCHANGE NEWS April New Item Information

2021.04.20 MK KASHIYAMA CORP. MK ITEM / INTERCHANGE NEWS April New Item Information ■BRAKE PAD Quotation MK No. Position Application Month D3188M Front Mazda CX-30 (1800cc,2000cc) 19.10- <JPN> Made in Japan April. 2021 FMSI No: D2275 D11463MH Rear Hyundai SANTA FE (2000cc,2200cc,2400cc,3500cc) 18.04- <USA,CAN,AUS,GEN,ME> Made in Indonesia April. 2021 FMSI No: D2199 D11475MH Front Hyudai H-100 (2500cc,2600cc) 16.10- <EUR,GEN,ME> Made in Indonesia Hyundai PORTER Ⅱ (2500cc) 16.08- <KOR> April. 2021 Kia K2500 (2500cc) 16.11- <EUR,GEN,ME> Kia BONGO Ⅲ (2400cc,2500cc) 16.08- <KOR> ■BRAKE SHOE Quotation MK No. Position Application Month K2395P Rear Toyota HILUX (2400cc,2500cc,2700cc,3000cc) 04.08- <EUR,MEX,GEN,AUS,GCC,IDN,LA> Made in Indonesia Toyota FORTUNER (2400cc,2700cc,2800cc) 05.01- <GEN,AUS,THA,GCC,IDN,PHL,VNM> April. 2021 *K2395 mounted with parking lever. April New Item Drawing Information ■BRAKE PAD & SHOE 2021.04.20 MK KASHIYAMA CORP. MK ITEM / INTERCHANGE NEWS Valuable Information ■Newly start Product at Indonesia Factory (Existing MK Item) *D3185MH are available in Indonesia from April order. ■Newly start Products with SHIM (Existing MK Item) <MADE IN INDONESIA> MK No. Origin Quotation Month MK No. Origin Quotation Month D0034H Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D3142H Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D1033MH Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D3155H Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D1044MH Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D4031MH Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D1087MH Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D5011H Made in Indonesia April. 2021 D1092MH Made in Indonesia April. -

Germans Praise New Peugeot Sedan Mclaren Expected to Reach New Zealand in July, the New 508 Has Already Gained Book Mazda Minagi CX5 an Award, Writes DAVE MOORE

White goods New Nissan Micra tested E Drive E10 Motoring Editor: Dave Moore Contact: [email protected] 03 943 2822 THE PRESS, CHRISTCHURCHSaturday Saturday, & February Sunday, February 5, 2011 5-6, 2011 E1 IN BRIEF DRIVE TRIVIA Head1 Germans praise new Peugeot sedan McLaren Expected to reach New Zealand in July, the new 508 has already gained book Mazda Minagi CX5 an award, writes DAVE MOORE. prize ❯❯ Mazda will show a new concept car at the Geneva salon in March hile it is only being available in two body styles: a Our giveaway this week is a copy called the Minagi and it is expected driven by automotive sedan measuring 4.79 metres and of McLaren – The Cars 1964-2008 by the car will reach production as the journalists for the first a station wagon two centimetres William Taylor, a rare book that CX5, replacing the ageing Tribute time this month, longer. Both will be produced in deserves a difficult question. All design and slotting-in under the WGerman motoring publication Rennes, France, for the European you have to do to be in to win is to successful CX7 and the CX9 Auto Zeitung has already given and export markets and later this tell us the name, or more properly models. The crossover concept is the new Peugeot 508 its first prize year in China, for the Chinese the number of McLaren’s first the first vehicle penned under new in its Auto Trophy awards, ahead market. road-going car, only two of which Mazda design boss, Ikeo Maeda, of 18 rival models in the import Both petrol and turbodiesel were made. -

Global Monthly Is Property of John Doe Total Toyota Brand

A publication from April 2012 Volume 01 | Issue 02 global europe.autonews.com/globalmonthly monthly Your source for everything automotive. China beckons an industry answers— How foreign brands are shifting strategies to cash in on the world’s biggest auto market © 2012 Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved. March 2012 A publication from Defeatglobal spurs monthly dAtA Toyota’s global Volume 01 | Issue 01 design boss Will Zoe spark WESTERN EUROPE SALES BY MODEL, 9 MONTHSRenault-Nissan’sbrought to you courtesy of EV push? www.jato.com February 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 2011 2010 change change 2011 2010 change change European sales Scenic/Grand Scenic ......... 116,475 137,093 –20,618 –15% A1 ................................. 73,394 6,307 +67,087 – Espace/Grand Espace ...... 12,656 12,340 +316 3% A3/S3/RS3 ..................... 107,684 135,284 –27,600 –20% data from JATO Koleos ........................... 11,474 9,386 +2,088 22% A4/S4/RS4 ..................... 120,301 133,366 –13,065 –10% Kangoo ......................... 24,693 27,159 –2,466 –9% A6/S6/RS6/Allroad ......... 56,012 51,950 +4,062 8% Trafic ............................. 8,142 7,057 +1,085 15% A7 ................................. 14,475 220 +14,255 – Other ............................ 592 1,075 –483 –45% A8/S8 ............................ 6,985 5,549 +1,436 26% Total Renault brand ........ 747,129 832,216 –85,087 –10% TT .................................. 14,401 13,435 +966 7% RENAULT ........................ 898,644 994,894 –96,250 –10% A5/S5/RS5 ..................... 54,387 59,925 –5,538 –9% RENAULT-NISSAN ............ 1,239,749 1,288,257 –48,508 –4% R8 ................................ -

Automobile Industry in India 30 Automobile Industry in India

Automobile industry in India 30 Automobile industry in India The Indian Automobile industry is the seventh largest in the world with an annual production of over 2.6 million units in 2009.[1] In 2009, India emerged as Asia's fourth largest exporter of automobiles, behind Japan, South Korea and Thailand.[2] By 2050, the country is expected to top the world in car volumes with approximately 611 million vehicles on the nation's roads.[3] History Following economic liberalization in India in 1991, the Indian A concept vehicle by Tata Motors. automotive industry has demonstrated sustained growth as a result of increased competitiveness and relaxed restrictions. Several Indian automobile manufacturers such as Tata Motors, Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra and Mahindra, expanded their domestic and international operations. India's robust economic growth led to the further expansion of its domestic automobile market which attracted significant India-specific investment by multinational automobile manufacturers.[4] In February 2009, monthly sales of passenger cars in India exceeded 100,000 units.[5] Embryonic automotive industry emerged in India in the 1940s. Following the independence, in 1947, the Government of India and the private sector launched efforts to create an automotive component manufacturing industry to supply to the automobile industry. However, the growth was relatively slow in the 1950s and 1960s due to nationalisation and the license raj which hampered the Indian private sector. After 1970, the automotive industry started to grow, but the growth was mainly driven by tractors, commercial vehicles and scooters. Cars were still a major luxury. Japanese manufacturers entered the Indian market ultimately leading to the establishment of Maruti Udyog. -

Ignition System Control Unit Switch Unit, Ignition System

CATALOGUE SUPPLEMENT IGNITION COILS AND IGNITION MODULES www.hella.com Pictograms and Abbreviations Productdetails PC applications OE 4 Cross references 5 6 41279 30185 Overview of order numbers 21913 1 Ignition System Control Unit Switch Unit, ignition system..........................................................................................................................................................................4 Ignition Coil Ignition Coil...................................................................................................................................................................................................9 2 Pictograms and Abbreviations from Chassis No. to Chassis No. Engine Code ... Manufacturer Restriction ... ports Number of ports ...x Required quantity + ABS Braking / Drive Dynamics, for vehicles with ABS + autom. Vehicle Equipment, for vehicles with auto- matic transmission BE Country Version, Belgium + CH Country Version, Switzerland + D Country Version, Germany engine ... from Engine Number to Engine No. + Europe Country Version, Europe FI Country Version, Finland IT Country Version, Italy + J Country Version, Japan Japan-made Vehicle Production Country, Japan LHD Driver Position, for left-hand drive vehicles Model ... from model year to model year +Model ... for model year + N Country Version, Norway NL Country Version, The Netherlands Orga ... from RP number to RP number RHD Driver Position, for right-hand drive vehi- cles + servo Vehicle Equipment, for vehicles with pow- er steering SV -

Europe Swings Toward Suvs, Minivans Fragmenting Market Sedans and Station Wagons – Fell Automakers Did Slightly Better Than Cent

AN.040209.18&19.qxd 06.02.2004 13:25 Uhr Page 18 ◆ 18 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE FEBRUARY 9, 2004 ◆ MARKET ANALYSIS BY SEGMENT Europe swings toward SUVs, minivans Fragmenting market sedans and station wagons – fell automakers did slightly better than cent. The only new product in an cent because of declining sales for 656,000 units or 5.5 percent. mass-market automakers. Volume otherwise aging arena, the Fiat the Honda HR-V and Mitsubishi favors the non-typical But automakers boosted sales of brands lost close to 2 percent of vol- Panda, was on sale for only four Pajero Pinin. over familiar sedans unconventional vehicles – coupes, ume last year, compared to 0.9 per- months of the year. In terms of brands leading the roadsters, minivans, sport-utility cent for luxury marques. European buyers seem to pro- most segments, Renault is the win- LUCA CIFERRI vehicles exotic cars and multi- Traditional European-brand gressively walk away from large ner with four. Its Twingo leads the spaces such as the Citroen Berlingo automakers dominate the tradi- sedans, down 20.3 percent for the minicar segment, but Renault also AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE – by 16.8 percent last year to nearly tional car, minivan and premium volume makers and off 11.1 percent leads three other segments that it 3 million units. segments, but Asian brands control in the upper-premium segment. created: compact minivan, Scenic; TURIN – Automakers sold 428,000 These non-traditional vehicle cat- virtually all the top spots in small, large minivan, Espace; and multi- more specialty vehicles last year in egories, some of which barely compact and large SUV segments. -

07On Arb Rated 2817010 R

2812010 RECOVERY POINT 70 SERIES CRUISER 19,175 2814010 RECOVERY POINT HILUX 05ON 19,500 2815010 RECOVERY POINT LC200|07ON ARB RATED 6,825 2817010 RECOVERY POINT GU PATROL 15,600 2821020 RECOVERY POINT PRADO 150 & FJ|LHS 8000KG ARB RATED 21,775 2821030 RECOVERY POINT PRADO 150 & FJ|RHS 8000KG ARB RATED 21,775 2838010 RECOVERY POINT NP300 NAVARA|15ON 4X4 8000KG 21,775 2840010 RECOVERY POINT RANGER/BT50 22,425 2840020 RECOVERY POINT RANG/BT50 2011ON 25,350 2848010 RECOVERY POINT DMAX/COL|12ON LHS 8000KG ARB RATED 21,450 2848020 RECOVERY POINT DMAX/COL|12ON RHS 8000KG ARB RATED 21,450 3105010 NUDGE BAR HONDA CRV TO 02 29,900 3105020 NUDGE BAR HONDA CRV 02-04 ONLY 36,400 3119010 NUDGE BAR X-TRAIL 2001 ON 28,275 3140010 NUDGE BAR MAZDA TRIBUTE TO 06 29,900 3140020 NUDGE BAR FORD ESCAPE TO 06 29,900 3141010 NUDGE BAR FALCON AU/BA/BF FORTE/STD 31,200 3141030 NUDGE BAR FORD TERRITORY TO 08 39,000 3149020 N/BAR C/DORE VY TO 04 CREWM/UTE 26,325 3149040 N/BAR C/DORE VX/VU 26,325 3149050 N/BAR C/DORE VZ SED/WAG & CREW 29,900 3154010 NUDGE BAR RAV 4 06/00 TO 09/03 31,200 3154020 NUDGE BAR RAV4 9/03 TO 06 30,225 3155010 NUDGE BAR HYUNDAI SANTA FE 35,750 3160010 NUDGE BAR KIA SORENTO TO 11/2006 31,200 3114020 NUDGE BAR ALLOY HILUX 6/11ON 48,750 3119020 NUDGE BAR ALLOY XTRAIL 01-8/07 41,925 3119030 NUDGE BAR ALLOY XTRAIL 9/07ON 51,350 3126020 NUDGE BAR ALLOY GRAND VITARA 08ON 47,125 3133020 N/BAR ALUM OUTLANDER|10ON 46,800 3141040 NUDGE BAR ALLOY TERRITORY 08ON 44,525 3151010 NUDGE BAR ALLOY CAPTIVA 41,275 3151020 N/BAR ALUM CAPTIVA 7|11ON 45,825 3154030 -

Small Suvs, Minicars Make Big Gains in 2006 the Renault Megane CC (Shown) Ended Peugeot’S 5-Year Reign at the Top of Luca Ciferri the Fastest-Growing Segment

AN_070402_18&19good.qxd 13.04.2007 8:58 Uhr Page 18 PAGE 18 · www.autonewseurope.com April 2, 2007 Market analysis by segment, European sales ROADSTER & CONVERTIBLE Small SUVs, minicars make big gains in 2006 The Renault Megane CC (shown) ended Peugeot’s 5-year reign at the top of Luca Ciferri the fastest-growing segment. Changing segments the roadster and convertible seg- Automotive News Europe Minicars, the No. 3 segment last year in ment. Peugeot’s 307 CC was No. 1 in terms of growth, increased 22.1 percent to Europe’s 2006 winners and losers 2004; the 206 CC led the other years. Rising fuel costs, growing concerns about 992,227 units thanks largely to strong Small SUV +63.6 2006 2005 % Change Seg. share % CO2 and a flurry of new products sparked sales of three cars built at Toyota and Upper premium +26.4 Renault Megane 32,344 42,514 -23.9% 13.4% a sales surge for small SUVs and minicars PSA/Peugeot-Citroen’s plant in Kolin, Minicar +22.1 Peugeot 307CC/306C 31,786 39,640 -19.8% 13.1% in Europe last year. Czech Republic. Peugeot 206 CC 29,833 43,518 -31.4% 12.3% The arrival of three new small SUVs Europe’s largest segment, small cars, Small minivan -13.6 VW Eos 21,759 59 – 9.0% helped the segment grow 63.6 percent to rose 7.0 percent to 3,811,009 units. The Premium roadster & convertible -10.9 Opel/Vauxhall Tigra TwinTop 20,406 32,633 -37.5% 8.4% 94,153 units in 2006, according to UK- second-biggest segment – lower-medium Lower medium -8.2 Mazda MX-5 19,288 9,782 97.2% 8.0% based market researcher JATO Dynamics. -

2007 MY Availabilty List

Gentex Corporation 2007 Model Year Interior Auto-Dimming and Exterior Auto-Dimming Mirrors Availability by Production Model (as of April 30, 2007) Interior Auto-Dimming Interior Advanced Exterior Auto- Make and Model Mirror(1) Feature(2) Dimming Mirror(3) Dealer / Distributor Installed Accessory and Aftermarket Acura RDX xx Ford Escape x x Ford E-Series x x Ford Expedition x x Ford Explorer x x Ford Explorer Sport Trac x x Ford F-150 xx Ford Five Hundred x x Ford Focus xx Ford Freestar x x Ford Freestyle x x Ford Fusion xx Ford Mustang x x Ford Ranger x x Ford Super Duty F-Series x x Honda Accord x Honda Civic x Honda CRV x Honda FRV x Jeep Compass x x Kia Optima xx Kia Sedona xx Kia Sorento xx Kia Spectra xx Kia Sportage x x Lincoln Aviator x x Lincoln Navigator x x Lincoln Town Car x x Mazda 3 xx Mazda 5 xx Mazda 6 xx Mazda CX-7 xx Mazda CX-9 xx Mazda MPV xx Mazda Tribute x x Mercury Grand Marquis x x Mercury Milan x x Mercury Montego x x Mercury Mountaineer x x Mercury Sable x x Mito Aftermarket x x Nissan Altima x x Nissan Frontier x Nissan Quest x x Nissan Tida x Nissan Titan xx Nissan Xterra x x Subaru B-9 Tribeca x x Subaru Baja xx 5/1/2007 Page 1 of 8 See explanations on page 7 for (1) (2) (3). Gentex Corporation 2007 Model Year Interior Auto-Dimming and Exterior Auto-Dimming Mirrors Availability by Production Model (as of April 30, 2007) Interior Auto-Dimming Interior Advanced Exterior Auto- Make and Model Mirror(1) Feature(2) Dimming Mirror(3) Subaru Forester x x Subaru Impreza x x Subaru Legacy x x Subaru Outback x x Suzuki -

Followup Evaluation of Electronic Stability Control Effectiveness in Australasia

FOLLOWUP EVALUATION OF ELECTRONIC STABILITY CONTROL EFFECTIVENESS IN AUSTRALASIA by Jim Scully & Stuart Newstead October 2010 Report No. 306 Project Sponsored By ii MONASH UNIVERSITY ACCIDENT RESEARCH CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY ACCIDENT RESEARCH CENTRE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Report No. Date ISBN ISSN Pages 306 October 2010 0 7326 2376 6 1835-4815 31 + Appendices (online) Title and sub-title: Follow Up Evaluation of Electronic Stability Control Effectiveness in Australasia Author(s): Scully, J.E. and Newstead. S.V. Sponsoring Organisation(s): This project was funded as contract research by the following organisations: Road Traffic Authority of NSW, Royal Automobile Club of Victoria Ltd, NRMA Motoring and Services, VicRoads, Royal Automobile Club of Western Australia Ltd, Transport Accident Commission, New Zealand Transport Agency, the New Zealand Automobile Association, Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads, Royal Automobile Club of Queensland, Royal Automobile Association of South Australia, South Australian Department of Transport Energy and Infrastructure and by grants from the Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Transport and the Road Safety Council of Western Australia Abstract: The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of ESC systems in reducing crash risk in Australia and New Zealand. This was a follow up to an earlier evaluation, with the present study making use of a greater quantity and range of crash data to employ an improved induced exposure method for controlling the effect of confounding factors. More data also meant that effectiveness could be measured in terms of reductions in serious injury crashes and effectiveness could be measured for specific types of crashes, such as rollover crashes and head on crashes. -

SSCC10105 2005 Ann. Rep.Qxd

2 0 1 3 A N N U A L R E P O R T O P P O R T U N I T I E S O P P O R T U N I T I E S Over a decade ago, STRATTEC and and ADAC was similarly recognized by WITTE Automotive of Velbert, Germany General Motors. formed a unique alliance. Soon after, In addition to our home markets of ADAC Automotive of Grand Rapids, North America and Europe, we have Michigan joined this alliance which we substantial VAST joint venture operations now call “VAST,” an acronym for Vehicle in China to serve the world’s fastest Access Systems Technology. growing market and an expanding VAST collectively represents the presence in Brazil. entire gamut of products used to access We believe that greater knowledge your vehicle. From keys and lock sets … and performance comes through synergy to handles and latches. From motorized and collaboration. This is why we have lift gates and power doors … to locking seized upon this VAST Opportunity to steering wheel columns. leverage our individual skills and our We view VAST as being vital to our collective reach in purchasing, engineering, future. Each company, individually and manufacturing, logistics and sales. together, is needed to successfully Individually, STRATTEC and our support the global vehicle access needs partners are highly capable regional of our customers. suppliers, each with specific vehicle We are proud to say that the access products. Together, we form a relationship we forged with strong partners unique, unified source of Vehicle Access has been recognized by our customers. -

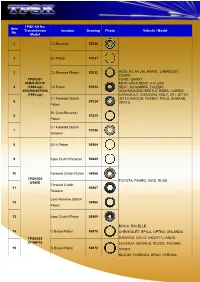

Item No. TPSK Kit No. Transmission Model Location Drawing Photo Vehicle / Model 1 TPSK001 01M/01N/01P (1989-Up) 095/096/097/098

TPSK Kit No. Item Transmission location Drawing Photo Vehicle / Model No. Model 1 C3 Retainer 57020 2 B2 Piston 57021 3 C2 Reverse Piston 57022 AUDI: A3, A4, A6, AVANT, CABRIOLET, COUPE TPSK001 FORD: GAlAXY 01M/01N/01P MERCEDES BENZ: V-CLASS 4 (1989-up) C3 Piston 57023 SEAT: ALHAMBRA, TOLEDO 095/096/097/098 VOLKSWAGEN: BEETLE, BORA, CABRIO, (1995-up) CARAVELLE, EUROVAN, GOLF, GTI, JETTA, C1 Forward Clutch JETTA WAGON, PASSAT, POLO, SHARAN, 5 57024 VENTO Piston B1 (Low/Reverse) 6 57025 Piston C1 Forward Clutch 7 57026 Retainer 8 B2-4 Piston 56964 9 Input Clutch Retainer 56965 10 Forward Clutch Piston 56966 TPSK002 TOYOTA: PASEO, VIOS, RUSH U540E Forward Clutch 11 56967 Retainer Low/ Reverse Clutch 12 56968 Piston 13 Input Clutch Piston 56969 BUICK: EXCELLE 14 C Brake Piston 56970 CHEVROLET: EPICA, OPTRA, ORLANDO TPSK003 DAEWOO: CIELO, LACETTI, LANOS, ZF4HP16 LEGANZA, MAGNUS, REZZO, TACOMA, 15 D Brake Piston 56970 VIVANT SUZUKI: FORENZA, RENO, VERONA TPSK Kit No. Item Transmission location Drawing Photo Vehicle / Model No. Model C2 Direct Clutch 16 56978 Piston C3 Reverse Clutch AUDI: A2,TT BMW: MINI CLUBMAN, MINI COOPER 17 TPSK004 56979 Retainer SAAB: 9'3 09G/09K/09M/ SEAT: ALTEA, LEON, TOLEDO TF-60SN/ C1 Forward Clutch SKODA: SUPERB TF-62SN 18 56980 VOLKSWAGEN: BEETLE, GOLF, JETTA, Retiner PASSAT, TIGUAN, TOURAN, TRANSPORTER C2 Direct Clutch 19 56981 Retainer 20 Servo Piston 56817 Low/Reverse Brake 21 56818 Piston Direct Clutch Apply 22 56731 Piston MAZDA: 2,3,3i, 3S, 3SP23, 323, 5, 6, 6i, 8, TPSK005 Forward Clutch Apply ATENZA, AXELA, WAGON, BIANTE, CX7, 23 56732 FN4A-EL Piston DEMIO, FAMILIA, MPV(VAN), PREMACY, PROTEGE, TRIBUTE, VERISA 24 Reverse Clutch Piston 56811 Forward Clutch 25 56816 Retainer 26 Direct Clutch Retainer 56815 27 Reverse Clutch Piston 57943 28 Servo Piston 56817 MAZDA: 2,3,3i, 3S, 3SP23, 323, 5, 6, 6i, 8, TPSK005A ATENZA, AXELA, WAGON, BIANTE, CX7, FN4A-EL DEMIO, FAMILIA, MPV(VAN), PREMACY, Low/Reverse Brake PROTEGE, TRIBUTE, VERISA 29 56818 Piston Direct Clutch Apply 30 56731 Piston TPSK Kit No.