Atb 2004-195 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Appellate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

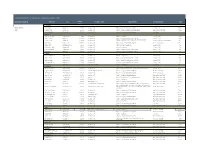

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

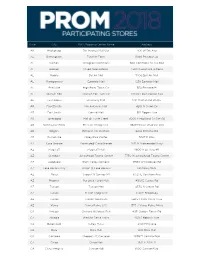

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Generalgrowthproperties

BUILT TO LEAD BUILT TO GROW BUILT TO PROSPER GENERALGROWTHBUILT PROPERTIES TO LASTANNUAL REPORT 2002 COMPANY PROFILE General Growth Properties and its predecessor companies have been in the shopping center busi- ness for nearly fifty years. It is the second largest regional mall Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) in the United States. General Growth owns, develops, operates and/or manages shopping malls in 39 states. GGP has ownership interests in, or management responsibility for, 160 regional shopping malls totaling more than 140 million square feet of retail space. The total retail space is inclusive of more than 16,000 retailers nationwide. General Growth provides investors with the opportunity to participate in the ownership of high-quality, income-producing real estate while maintaining liquidity. Our primary objective is to provide increasing dividends and capital appreciation for our shareholders. Creating shareholder value is the company’s mission. The Bucksbaum family, which founded General Growth, is still engaged in the operation of the company’s day-to-day business activities. As owners of a major stake in the company, General Growth management’s interests are aligned with those of each and every GGP shareholder. CONTENTS Shareholders’ Letter 4 Operating Principles 7 Portfolio 17 Financial Review 29 Directors and Officers 85 Corporate Information 86 Financial Highlights SHOPPING CENTERS OWNED at year end * 1997 64 1998 84 1999 93 2000 95 2001 97 2002 125 TOTAL SQUARE FOOTAGE OWNED in millions 1997 52 1998 71 1999 83 2000 85 2001 89 2002 114 REAL ESTATE ASSETS AT COST in millions 1997 $2,590 1998 $4,760 1999 $6,237 2000 $6,735 2001 $7,319 2002 $9,902 MALL SHOP SALES in millions ** 1997 $2,651 1998 $5,176 1999 $6,931 2000 $7,243 2001 $7,326 2002 $9,061 DIVIDEND GROWTH PER SHARE dollar/share declared 1997 $1.80 1998 $1.88 1999 $1.98 2000 $2.06 2001 $2.36 2002 $2.74 FFO GROWTH dollar/share 1997 $2.89 1998 $3.35 1999 $4.02 2000 $4.42 2001 $4.96 2002 $5.58 * Includes regional malls only. -

Northshore Mall

NORTHSHORE MALL PEABODY (BOSTON), MASSACHUSETTS The largest mall in New England, Northshore Mall serves Greater Boston’s 4 densely populated, affluent Northshore market and New Hampshire’s Southern Sea APARTMENT Coast. A recent renovation and expansion added Nordstrom to the mall’s strong lineup COMPLEXES of department store favorites, more than Avalon Essex Apartments: Three complexes 120 popular specialty retailers, and seven near Northshore Mall full-service restaurants. Accessible from Route 128, I-95, and US 1, Northshore Mall Brooksby Village: 90-acre campus, adults 62 is convenient not only to the trade area’s and older, 400 employees affluent shoppers, but also to the significant tourist traffic from adjacent historic Salem 7 Essex Place: Newly renovated, across from and Marblehead, the yachting capital Northshore Mall 3 of the world. Esquire Apartments: 102 units 6 Terrace Estates: Adjacent to Northshore Mall, 4 nine styles of housing 1 2 NORTHSHORE MALL 5 Major Retailers: Nordstrom, Macy’s, Macy’s Furniture & Men’s Store, JCPenney, Sears, Barnes & Noble, The Container Store, CORPORATE ULTA Beauty, DSW, Uniqlo, XXI Forever 4 HEADQUARTERS 1 Analogic: Multinational corporation’s main GLA: 1,592,000 Sq. Ft. RTE. 114 facility, nearly 400 employees 4 Boston Acoustics: Private company, 83 employees* 2 5 Goodrich: Private company, 150 employees* 7 HOTELS 4 Courtyard Marriott Danvers: 118 rooms and 7 suites, 1,000 square feet of meeting space 6 DoubleTree by Hilton: Newly renovated in 2013, 4 346 rooms, 30,000 square feet of meeting MAJOR OFFICE space, health club, indoor water park* COMPLEXES Holiday Inn & Suites: 183 rooms, Centennial Park Peabody: Business park 23 suites, more than 10,000 square featuring headquarters of many multinational feet of meeting space* 2 corporations* Marriott Peabody: 354 rooms and suites, RTE. -

Child Labor Summer 2008 Sweep Citation List

Child Labor Sweep August 5, 2008 Citation List Company Mall Violation Counts Penalty Adidas Promotional Retail Wrentham Outlets Employment of minor w/out work permit 4$ 200.00 Hollister Burlington Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 3$ 300.00 CVS Pharmacy Burlington Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 2$ 200.00 Hollister Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 8$ 400.00 Rainbow USA, Inc. Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 The Finish Line, Inc. Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 Abercrombie Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 6$ 300.00 Against All Odds Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 2$ 100.00 DSW, Inc. Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 Delia's Holyoke Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 2$ 100.00 Circuit City Allstate Rd. Dorchester Employment of minor w/out work permit 2$ 100.00 Office Max Allstate Rd. Dorchester Employment of minor w/out work permit 3$ 150.00 Footlocker Liberty Tree Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 Steve & Barry's Liberty Tree Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 12$ 600.00 Aeropostale, Inc. Cape Cod Mall Employment of minor after 10:00 p.m. 1$ 100.00 Big K-Mart, Inc. Fall River Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 A.J. Wright, Inc. Fall River Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 50.00 Old Navy Walpole Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 4$ 200.00 Hollister Galleria Mall, Taunton Employment of minor w/out work permit 3$ 50.00 Footlocker Galleria Mall, Taunton Employment of minor w/out work permit 1$ 100.00 Hollister Cape Cod Mall Employment of minor w/out work permit 3$ 300.00 K.B. -

Cambridge Survival Guide Was 6 BEST BITES in BOSTON Developed by Spouses at Harvard University

1 Table of Contents CAMBRIDGE 2 SHOPPING Furniture Home Improvement SURVIVAL Just about Everything Pharmacies GUIDE 3 Supermarkets Warehouse Superstores Welcome to Westgate Apartments at MIT! International Supermarkets 4 Farmer’s Markets This booklet will highlight shopping, food Clothes guides, activities and essential tips for getting Fabric/Crafts around town -- with or without a car. Office Supplies and Electronics We hope you find this a helpful resource and Video/DVD Rental enjoy your time in the Cambridge/Boston area. Shopping Malls The original Cambridge Survival Guide was 6 BEST BITES IN BOSTON developed by spouses at Harvard University. Cheap Food This booklet is based the original guide, on some Special Date Nights various other resources, the Internet, many 7 Worth the Splurge additions from the Eastgate Graduate Family Friendly Coordinators, advice from former and present 8 Ice Cream/Desserts Westgate residents, and a few additions of our 9 GETTING AROUND own. (Transport, Guides) 10 SUBWAY TIPS Enjoy! 12 ACTIVITIES 15 DAY TRIPS The Westgate Graduate Coordinators 17 WEEKEND GETAWAYS Please e-mail with any questions you may have: [email protected] 2 SHOPPING Yard Sales Here are a few resources to make your Particularly take a look in upscale suburbs or new house a home. in/around student housing towards the end of the school year and throughout the summer. Big FURNITURE & HOUSEWARE sales are also sometimes listed in the Boston Antique Shops - along Charles Street Globe. Bernie and Phyl’s Furniture 1 East Street, Cambridge -

Consumption and Inequality Fall 2012

Honors 391 A/D: Consumption and Inequality University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Spring 2012 Course Meetings: Tuesdays 9:30-10:20am, Dickinson 114 Who: Joya Misra Kyla Walters Where: Machmer Hall W33e Thompson 638 When: Tues 10:30 am-11:30 am Thurs 8:30-10:30 am Email: [email protected] [email protected] Site: https://moodle.umass.edu/course/view.php?id=831 Course Description Consumption is an undeniable part of our lives. Whether we’re striving to be out with the old and in with the new, bargain hunting at neighborhood tag sales, or restricting produce purchases to locally grown organic vegetables, our actions, beliefs, ideals, bodily behaviors, and monetary exchanges form a constellation of consumption. This course will survey how scholars examine social phenomena related to consumption and consumerism, including theories about globalization, culture, inequality, gender, and intersectionality. We will consider three main themes over the course of the semester: 1) the historical, political, and economic underpinnings of consumption; 2) cultural aspects of consumption and image representation in relation to racial, ethnic, gender, sexuality, and class inequality reproduction, and 3) retail and service work. Course Requirements: One of the best parts of a seminar class is in having people with different backgrounds and experiences hash out a given topic. Our goal will not be to all agree – but to thoughtfully, respectfully, and energetically push each other forward in our understandings of the materials and of our own viewpoints. You need not read or respond to the materials the same way we do, but you should be prepared to take a position and argue for it! Much of your course grade will be based on exactly that – so being engaged is your best chance at doing well in the class. -

Indianapolis, Indiana Burlington (Boston

BUSINESSBUSINESS CARD CARD DIE DIE AREA AREA 225 West Washington Street Indianapolis, IN 46204 (317) 636 1600 simon.com 225 West Washington Street Indianapolis, IN 46204 (317) 636-1600 simon.com Simon Property Group (NYSE: SPG) is an S&P 100 company and a leader in the global retail real estate industry. INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA Information as of 5/1/16 Simon is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). BURLINGTON (BOSTON), MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON HIP MEETS HISTORIC Boston is the largest city in New England delivering an exciting blend of the historic and the cutting edge. — Burlington Mall® is located just 15 miles from downtown Boston and is convenient to the entire Boston metro area with more than 4.6 million residents. — Boston is home to the headquarters of 13 Fortune 500 companies and over 100 colleges and universities, including Harvard University, Boston College, Boston University, MIT, Northeastern University, and Tufts University. — Lahey Hospital and Medical Center is less than one mile away from the center, has over 4,500 employees, and serves over 3,000 patients each day. — Five major office complexes featuring eight corporate headquarters are nearby. WHERE BOSTON SHOPS Burlington Mall serves the affluent northwest Boston metro area. — A 2008 redevelopment added to the already impressive lineup of upscale anchors that include Nordstrom, Lord & Taylor, and Macy’s. — With the addition of Primark in Fall 2016, Burlington Mall continues to elevate its already distinctive retail and dining experience. BY THE NUMBERS Anchored by Five Department Stores Nordstrom, Lord & Taylor, Macy’s, Primark (opening 2016), Sears Square Footage Burlington Mall spans 1,317,000 square feet. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 961 Filed 07/15/21 Page 1 of 27 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ------------------------------------------------------------ x In re: : Chapter 11 : 1 FHC HOLDINGS CORPORATION, et al., : Case No. 20-13076 (BLS) : Debtors. : Jointly Administered ------------------------------------------------------------ x CERTIFICATION OF STRETTO REGARDING TABULATION OF VOTES IN CONNECTION WITH THE DEBTORS’ FIRST AMENDED COMBINED DISCLOSURE STATEMENT AND CHAPTER 11 PLAN OF LIQUIDATION I, Alexa T. Westmoreland, depose and say under the penalty of perjury: 1. I am a Director at Stretto, which has offices located at 410 Exchange, Suite 100, Irvine, CA 92602. I am over the age of eighteen years and neither I nor Stretto is a party to these proceedings. I am duly authorized to submit this certification on behalf of Stretto (this “Certification”). Except as otherwise indicated, all matters set forth herein are based upon my personal knowledge, and, if called as a witness, I could and would testify competently thereto. 2. I submit this Certification in connection with the tabulation of votes to accept or reject the Debtors’ First Amended Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation filed in the above-captioned cases [D.I. 737] (as amended, supplemented, or modified from time to time, the “Plan”).2 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are FHC Holdings Corporation (f/k/a Francesca’s Holdings Corporation) (4704), FHC LLC (f/k/a Francesca’s LLC) (2500), FHC Collections, Inc. (f/k/a Francesca’s Collections, Inc.) (4665), and FHC Services Corporation (f/k/a Francesca’s Services Corporation) (5988). -

2019 Property Portfolio Simon Malls®

The Shops at Clearfork Denver Premium Outlets® The Colonnade Outlets at Sawgrass Mills® 2019 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 THE SIMON EXPERIENCE WHERE BRANDS & COMMUNITIES COME TOGETHER SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 ABOUT SIMON Simon® is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management, and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). Our industry-leading retail properties and investments across North America, Europe, and Asia provide shopping experiences for millions of consumers every day and generate billions in annual sales. For more information, visit simon.com. · Information as of 12/16/2019 3 SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME More than real estate, we are a company of experiences. For our guests, we provide distinctive shopping, dining, and entertainment. For our retailers, we offer the unique opportunity to thrive in the best retail real estate in the best markets. From new projects and redevelopments to acquisitions and mergers, we are continuously evaluating our portfolio to enhance the Simon experience—places where people choose to shop and retailers want to be. 4 LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME WE DELIVER: SCALE A global leader in the ownership of premier shopping, dining, entertainment, and mixed-use destinations, including Simon Malls®, Simon Premium Outlets®, and The Mills® QUALITY Iconic, irreplaceable properties in great locations INVESTMENT Active portfolio management increases productivity and returns GROWTH Core business and strategic acquisitions drive performance EXPERIENCE Decades of expertise in development, ownership, and management That’s the advantage of leasing with Simon. -

Another Reason to 1 Hatesuvs

~ .... Allston an shot in Roslindale ousing project ~ 5 ~ ~~ I ? .... .....~ Wo (\I I-*l .... 0 0 (I) ~~ti! 'f ~ ..J~i!e i3 w~ ~ l:t~cta lll'lnmunity Newspaper Company www.allstonbrightontab.com FRIDAY, JULY 1, 2005 Vol. 9, No. 47 Bl 32 Pages iW 3 Sections 75¢ · __.,____ ..;;,_.wi... ..... STAFF PHOTO BY KATE FLOCJ The bankrupt Prov dent Nursing Home at 1501 Commonwealth Ave., which finally found a new home for Its last patients. Nursing home shuts doors By Audltl Guha STArr WRITER ith the owner of the Provident Skilled W Nursing Home in Brighton filing for bankrnptcy in Florida, the place's last pa tient was successfully transferred to another nursing home Tuesday ard the building is expected to be va cated soon, city officials said. "All patients have been moved," said Meri ta Hop kins, the mayor's spokeswoman at City Hall. ''The business is taking 30 to 45 days to move out and STAFF PHOTO BY DAVID GORDON Marcelle Goggins with the hot aJr balloon company Above Earth's Plane tries to hold onto to her balloon Saturday ftemoon. The city was going to will report back progress to the court." celebrate Its 375th anniversary rith free rides at Shea Field, ~ut It had to cancel because of high winds. Owned by R chard Wolfe through the Hillard Development C rp., which filed for bankruptcy in PROVIDENT, page J..5 OME, LOW OL By Auditl Guha was too s ·ong at time . STAFF WRITER I "It sou oded like fun ··one ing about ballooning is that you be The wind popped high hopes at St. -

Ticketmaster and Simon Property Group Bring Tickets to Shopping Malls Across the Country

TICKETMASTER AND SIMON PROPERTY GROUP BRING TICKETS TO SHOPPING MALLS ACROSS THE COUNTRY - Ticketmaster Tickets Now Available at More Than 70 Simon Mall Locations Nationwide - LOS ANGELES – November 2, 2011 – Ticketmaster, a Live Nation Entertainment company (NYSE:LYV), and Simon Property Group, Inc. (NYSE:SPG), the country's largest owner, developer and manager of high quality retail real estate have extended and expanded their unique relationship, opening twenty-two additional Ticketmaster ticket purchasing locations in Simon malls, for a total of seventy-two Simon Malls now offering Ticketmaster event tickets at Guest Services. “Ticketmaster’s retail outlets at our Guest Service locations have been a convenient amenity for millions of our shoppers. We are pleased to be extending and expanding our relationship with Ticketmaster,” said Dennis Tietjen, senior vice president of Simon Brand Ventures, a division of Simon Property Group. “Recognizing the strategic value of Simon as a distribution channel, we worked together, to deliver a solution that would raise awareness of events and provide an onsite ticket purchasing option for our fans in their neighborhood shopping mall,” said Sandy Gaare, executive vice president of retail partners, Ticketmaster. “Ticketmaster is committed to providing convenient ticket purchasing options through our online store and our thousands of retail outlets.” In each of the seventy-two participating Simon malls, fans may purchase tickets at the Guest Service desk from a Simon associate. Tickets are printed on traditional ticket stock and are produced on location. Ticketmaster Retail Centers in Simon Malls: Apple Blossom Mall (Winchester, VA) Coral Square (Coral Springs, FL) Arsenal Mall® (Watertown, MA) Crystal Mall (Waterford, CT) Arundel Mills (Hanover, MD) Dadeland Mall (Miami, FL) Auburn Mall (Auburn, MA) DeSoto Square (Bradenton, FL) Battlefield Mall (Springfield, MO) Edison Mall (Ft.