Who's Afraid of Background Independence?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Homological Kنhler-De Rham Differential Mechanism Part I

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Advances in Mathematical Physics Volume 2011, Article ID 191083, 14 pages doi:10.1155/2011/191083 Research Article The Homological Kahler-De¨ Rham Differential Mechanism part I: Application in General Theory of Relativity Anastasios Mallios and Elias Zafiris Department of Mathematics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece Correspondence should be addressed to Elias Zafiris, ezafi[email protected] Received 7 March 2011; Accepted 12 April 2011 Academic Editor: Shao-Ming Fei Copyright q 2011 A. Mallios and E. Zafiris. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The mechanism of differential geometric calculus is based on the fundamental notion of a connection on a module over a commutative and unital algebra of scalars defined together with the associated de Rham complex. In this communication, we demonstrate that the dynamical mechanism of physical fields can be formulated by purely algebraic means, in terms of the homological Kahler-De¨ Rham differential schema, constructed by connection inducing functors and their associated curvatures, independently of any background substratum. In this context, we show explicitly that the application of this mechanism in General Relativity, instantiating the case of gravitational dynamics, is related with the absolute representability of the theory in the field of real numbers, a byproduct of which is the fixed background manifold construct of this theory. Furthermore, the background independence of the homological differential mechanism is of particular importance for the formulation of dynamics in quantum theory, where the adherence to a fixed manifold substratum is problematic due to singularities or other topological defects. -

Loop Quantum Gravity Alejandro Perez, Centre De Physique Théorique and Université Aix-Marseille II • Campus De Luminy, Case 907 • 13288 Marseille • France

features Loop quantum gravity Alejandro Perez, Centre de Physique Théorique and Université Aix-Marseille II • Campus de Luminy, case 907 • 13288 Marseille • France. he revolution brought by Einstein’s theory of gravity lies more the notion of particle, Fourier modes, vacuum, Poincaré invariance Tin the discovery of the principle of general covariance than in are essential tools that can only be constructed on a given space- the form of the dynamical equations of general relativity. General time geometry.This is a strong limitation when it comes to quantum covariance brings the relational character of nature into our descrip- gravity since the very notion of space-time geometry is most likely tion of physics as an essential ingredient for the understanding of not defined in the deep quantum regime. Secondly, quantum field the gravitational force. In general relativity the gravitational field is theory is plagued by singularities too (UV divergences) coming encoded in the dynamical geometry of space-time, implying a from the contribution of arbitrary high energy quantum processes. strong form of universality that precludes the existence of any non- This limitation of standard QFT’s is expected to disappear once the dynamical reference system—or non-dynamical background—on quantum fluctuations of the gravitational field, involving the dynam- top of which things occur. This leaves no room for the old view ical treatment of spacetime geometry, are appropriately taken into where fields evolve on a rigid preestablished space-time geometry account. But because of its intrinsically background dependent (e.g. Minkowski space-time): to understand gravity one must definition, standard QFT cannot be used to shed light on this issue. -

![Arxiv:1911.01307V1 [Gr-Qc] 4 Nov 2019 What ‘True Names’ This Article Refers to These By](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0763/arxiv-1911-01307v1-gr-qc-4-nov-2019-what-true-names-this-article-refers-to-these-by-830763.webp)

Arxiv:1911.01307V1 [Gr-Qc] 4 Nov 2019 What ‘True Names’ This Article Refers to These By

Lie Theory suffices to understand, and Locally Resolve, the Problem of Time Edward Anderson Abstract The Lie claw digraph controls Background Independence and thus the Problem of Time and indeed the Fundamental Nature of Physical Law. This has been established in the realms of Flat and Differential Geometry with varying amounts of extra mathematical structure. This Lie claw digraph has Generator Closure at its centre (Lie brackets), Relationalism at its root (implemented by Lie derivatives), and, as its leaves, Assignment of Observables (zero commutants under Lie brackets) and Constructability from Less Structure Assumed (working if generator Deformation leads to Lie brackets algebraic Rigidity). This centre is enabled by automorphisms and powered by the Generalized Lie Algorithm extension of the Dirac Algorithm (itself sufficing for the canonical subcase, for which generators are constraints). The Problem of Time’s facet ordering problem is resolved. 1 dr.e.anderson.maths.physics *at* protonmail.com 1 Introduction Over 50 years ago, Wheeler, DeWitt and Dirac [6, 4] found a number of conceptual problems with combining General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM). Kuchař and Isham [11] subsequently classified attempted resolutions of these problems; see [14] for a summary. They moreover observed that attempting to extend one of these Problem of Time facet’s resolution to include a second facet has a strong tendency to interfere with the first resolution (nonlinearity). The Author next identified [15, 20] each facet’s nature in a theory-independent manner. This is in the form of clashes between background-dependent (including conventional QM) and background-independent Physics (including GR). -

Chapter 9: the 'Emergence' of Spacetime in String Theory

Chapter 9: The `emergence' of spacetime in string theory Nick Huggett and Christian W¨uthrich∗ May 21, 2020 Contents 1 Deriving general relativity 2 2 Whence spacetime? 9 3 Whence where? 12 3.1 The worldsheet interpretation . 13 3.2 T-duality and scattering . 14 3.3 Scattering and local topology . 18 4 Whence the metric? 20 4.1 `Background independence' . 21 4.2 Is there a Minkowski background? . 24 4.3 Why split the full metric? . 27 4.4 T-duality . 29 5 Quantum field theoretic considerations 29 5.1 The graviton concept . 30 5.2 Graviton coherent states . 32 5.3 GR from QFT . 34 ∗This is a chapter of the planned monograph Out of Nowhere: The Emergence of Spacetime in Quantum Theories of Gravity, co-authored by Nick Huggett and Christian W¨uthrich and under contract with Oxford University Press. More information at www.beyondspacetime.net. The primary author of this chapter is Nick Huggett ([email protected]). This work was sup- ported financially by the ACLS and the John Templeton Foundation (the views expressed are those of the authors not necessarily those of the sponsors). We want to thank Tushar Menon and James Read for exceptionally careful comments on a draft this chapter. We are also grateful to Niels Linnemann for some helpful feedback. 1 6 Conclusions 35 This chapter builds on the results of the previous two to investigate the extent to which spacetime might be said to `emerge' in perturbative string the- ory. Our starting point is the string theoretic derivation of general relativity explained in depth in the previous chapter, and reviewed in x1 below (so that the philosophical conclusions of this chapter can be understood by those who are less concerned with formal detail, and so skip the previous one). -

String Field Theory, Nucl

1 String field theory W. TAYLOR MIT, Stanford University SU-ITP-06/14 MIT-CTP-3747 hep-th/0605202 Abstract This elementary introduction to string field theory highlights the fea- tures and the limitations of this approach to quantum gravity as it is currently understood. String field theory is a formulation of string the- ory as a field theory in space-time with an infinite number of massive fields. Although existing constructions of string field theory require ex- panding around a fixed choice of space-time background, the theory is in principle background-independent, in the sense that different back- grounds can be realized as different field configurations in the theory. String field theory is the only string formalism developed so far which, in principle, has the potential to systematically address questions involv- ing multiple asymptotically distinct string backgrounds. Thus, although it is not yet well defined as a quantum theory, string field theory may eventually be helpful for understanding questions related to cosmology arXiv:hep-th/0605202v2 28 Jun 2006 in string theory. 1.1 Introduction In the early days of the subject, string theory was understood only as a perturbative theory. The theory arose from the study of S-matrices and was conceived of as a new class of theory describing perturbative interactions of massless particles including the gravitational quanta, as well as an infinite family of massive particles associated with excited string states. In string theory, instead of the one-dimensional world line 1 2 W. Taylor of a pointlike particle tracing out a path through space-time, a two- dimensional surface describes the trajectory of an oscillating loop of string, which appears pointlike only to an observer much larger than the string. -

Loop Quantum Gravity

QUANTUM GRAVITY Loop gravity combines general relativity and quantum theory but it leaves no room for space as we know it – only networks of loops that turn space–time into spinfoam Loop quantum gravity Carlo Rovelli GENERAL relativity and quantum the- ture – as a sort of “stage” on which mat- ory have profoundly changed our view ter moves independently. This way of of the world. Furthermore, both theo- understanding space is not, however, as ries have been verified to extraordinary old as you might think; it was introduced accuracy in the last several decades. by Isaac Newton in the 17th century. Loop quantum gravity takes this novel Indeed, the dominant view of space that view of the world seriously,by incorpo- was held from the time of Aristotle to rating the notions of space and time that of Descartes was that there is no from general relativity directly into space without matter. Space was an quantum field theory. The theory that abstraction of the fact that some parts of results is radically different from con- matter can be in touch with others. ventional quantum field theory. Not Newton introduced the idea of physi- only does it provide a precise mathemat- cal space as an independent entity ical picture of quantum space and time, because he needed it for his dynamical but it also offers a solution to long-stand- theory. In order for his second law of ing problems such as the thermodynam- motion to make any sense, acceleration ics of black holes and the physics of the must make sense. -

Problem of Time and Background Independence: Classical Version's

Problem of Time and Background Independence: classical version’s higher Lie Theory Edward Anderson1 Abstract A local resolution of the Problem of Time has recently been given, alongside reformulation as a local theory of Background Independence. The classical part of this requires just Lie’s Mathematics, much of which is basic: i) Lie derivatives to encode Relationalism. ii) Lie brackets for Closure giving Lie algebraic structures. iii) Observables defined by a Lie brackets relation, in the constrained canonical case as explicit PDEs to be solved using Lie’s flow method, and themselves forming Lie algebras. iv) Lattices of constraint algebraic substructures induce dual lattices of observables subalgebras. The current Article focuses on two pieces of ‘higher Lie Theory’ that are also required. Preliminarily, we extend Dirac’s Algorithm for Constraint Closure to ‘Lie’s Algorithm’ for Generator Closure. 1) We then reinterpret ‘passing families of theories through the Dirac Algorithm’ – a method used for Spacetime Construction (from space) and getting more structure from less structure assumed more generally – as the Dirac Rigidity subcase of Lie Rigidity. We also provide a Foundations of Geometry example of specifically Lie rather than Dirac Rigidity, to illustrate merit in extending from Dirac to Lie Algorithms. We point to such rigidity providing a partial cohomological (and thus global) selection principle for the Comparative Theory of Background Independence. 2) We finally pose the universal (theory-independent) analogue of GR’s Refoliation Invariance for the general Lie Theory: Reallocation of Intermediary-Object Invariance. This is a commuting pentagon criterion: in evolving from an initial object to a final object, does switching which intermediary object one proceeds via amount to at most a difference by an automorphism of the final object? We argue for this to also be a selection principle in the Comparative Theory of Background Independence. -

Topspin Networks in Loop Quantum Gravity

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Physics Faculty Publications Physics 2012 Topspin Networks in Loop Quantum Gravity Christopher L. Duston Merrimack, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/phy_facpub Part of the Cosmology, Relativity, and Gravity Commons, and the Quantum Physics Commons This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Repository Citation Duston C, Topspin Networks in Loop Quantum Gravity, Class. Quantum Grav. 29, 205015 (2012). This Article - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topspin networks in loop quantum gravity Christopher L Duston Physics Department, The Florida State University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We discuss the extension of loop quantum gravity to topspin networks, a proposal which allows topological information to be encoded in spin networks. We will show that this requires minimal changes to the phase space, C*-algebra and Hilbert space of cylindrical functions. We will also discuss the area and Hamiltonian operators, and show how they depend on the topology. This extends the idea of “background independence” in loop quantum gravity to include topology as well as geometry. It is hoped this work will confirm the usefulness of the topspin network formalism and open up several new avenues for research into quantum gravity. PACS numbers: 04.60.-m,04.60.Pp 1. Introduction In this paper we explore an idea recently introduced by [1], which incorporates topological information into the existing structures of loop quantum gravity. -

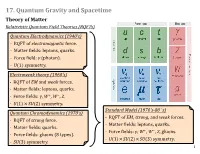

17. Quantum Gravity and Spacetime Theory of Matter Relativistic Quantum Field Theories (Rqfts) Quantum Electrodynamics (1940'S) - RQFT of Electromagnetic Force

17. Quantum Gravity and Spacetime Theory of Matter Relativistic Quantum Field Theories (RQFTs) Quantum Electrodynamics (1940's) - RQFT of electromagnetic force. - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Force field: γ (photon). - U(1) symmetry. Electroweak theory (1960's) - RQFT of EM and weak forces. - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Force fields: γ, W+, W−, Z. - U(1) × SU(2) symmetry. Standard Model (1970's-80’s) Quantum Chromodynamics (1970's) - RQFT of EM, strong, and weak forces. - RQFT of strong force. - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Matter fields: quarks. - Force fields: γ, W+, W−, Z, gluons. - Force fields: gluons (8 types). - U(1)×SU(2)×SU(3) symmetry. - SU(3) symmetry. 1 17. Quantum Gravity and Spacetime Theory of Matter Theory of Spacetime Relativistic Quantum Field Theories (RQFTs) General Relativity (GR) (1916) Quantum Electrodynamics (1940's) - Classical (non-quantum) theory of gravitational force. - RQFT of electromagnetic force. - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Diff(M) symmetry. - Force field: γ (photon). - U(1) symmetry. Electroweak theory (1960's) - RQFT of EM and weak forces. Inconsistent! - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Force fields: γ, W+, W−, Z. - U(1) × SU(2) symmetry. Standard Model (1970's-80’s) Quantum Chromodynamics (1970's) - RQFT of EM, strong, and weak forces. - RQFT of strong force. - Matter fields: leptons, quarks. - Matter fields: quarks. - Force fields: γ, W+, W−, Z, gluons. - Force fields: gluons (8 types). - U(1)×SU(2)×SU(3) symmetry. - SU(3) symmetry. 2 Theory of Matter Theory of Spacetime Relativistic Quantum Field Theories General Relativity - Flat Minkowski spacetime, unaffected by - Curved Lorentzian spacetimes, matter. dynamically affected by matter. - Matter/energy and forces are quantized. -

Concept of Time in Canonical Quantum Gravity and String Theory

Fourth International Workshop DICE2008 IOP Publishing Journal of Physics: Conference Series 174 (2009) 012021 doi:10.1088/1742-6596/174/1/012021 Concept of Time in Canonical Quantum Gravity and String Theory Claus Kiefer Institut f¨urTheoretische Physik, Universit¨atzu K¨oln,Z¨ulpicherStraße 77, 50937 K¨oln,Germany. Abstract. The accommodation of gravity into the quantum framework will entail changes for the concepts of space and time at the most fundamental level. Here I shall review the concept of time, but include also some remarks on the concept of space. After a general introduction, I shall discuss time in canonical quantum gravity and its application to cosmology. The most important feature is the fundamental timelessness of the theory. I shall conclude with a brief discussion of space and time in string theory. 1. The Problem of Time There exist many reasons why a final quantum theory of gravity is not yet at our disposal. First, there is the persistent lack of experiments which could serve as a trustful guide. Second, there are many mathematical problems. An third, there are conceptual problems which have no counterparts in other quantum theories. Among them is the problem of time, which is the subject of my contribution. In the following, I shall give a brief introduction to this problem and present some ideas about the role that time plays in some of the current approaches to quantum gravity – canonical quantum gravity and string theory. A more detailed exposition can be found, for example, in my monograph [1]; the reader can find there also references to the original literature and other sources. -

Status of Background-Independent Coarse Graining in Tensor Models for Quantum Gravity

universe Article Status of Background-Independent Coarse Graining in Tensor Models for Quantum Gravity Astrid Eichhorn 1,2, Tim Koslowski 3 and Antonio D. Pereira 2,* 1 CP3-Origins, University of Southern Denmark, Campusvej 55, DK-5230 Odense M, Denmark; [email protected] 2 Institut für Theoretische Physik, Universität Heidelberg, Philosophenweg 16, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM, Apartado Postal 70-543, Coyoacán 04510, Ciudad de México, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 30 January 2019; Published: 5 February 2019 Abstract: A background-independent route towards a universal continuum limit in discrete models of quantum gravity proceeds through a background-independent form of coarse graining. This review provides a pedagogical introduction to the conceptual ideas underlying the use of the number of degrees of freedom as a scale for a Renormalization Group flow. We focus on tensor models, for which we explain how the tensor size serves as the scale for a background-independent coarse-graining flow. This flow provides a new probe of a universal continuum limit in tensor models. We review the development and setup of this tool and summarize results in the two- and three-dimensional case. Moreover, we provide a step-by-step guide to the practical implementation of these ideas and tools by deriving the flow of couplings in a rank-4-tensor model. We discuss the phenomenon of dimensional reduction in these models and find tentative first hints for an interacting fixed point with potential relevance for the continuum limit in four-dimensional quantum gravity. -

Developments in String Field Theory

Developments in String Field Theory Ashoke Sen Harish-Chandra Research Institute, Allahabad, India Okinawa, June 2018 1 What is string field theory? String field theory is a quantum field theory with infinite number of fields in which perturbative amplitudes are computed by summing over Feynman diagrams. Each Feynman diagram can be represented as an integral over the moduli space of a Riemann surface with – the correct integrand (as in world-sheet description) – but only a limited range of integration. Sum over all Feynman diagrams reproduces the integration over the whole moduli space. 2 Why string field theory? 1. Since it is a quantum field theory with action, the S-matrix can be represented as path integral over string fields – could possibly give a non-perturbative formulation of string theory (has not been successful so far) 2. Classical string field theory may be useful for finding new classical solutions of string field theory that are not easily describable in conventional world-sheet formulation (reasonably successful for open string field theory) 3 3. For a given amplitude, the usual world-sheet description of string perturbation theory gives one term at every loop order – usually considered an advantage, but this may not always be the case. 4 Example: In a quantum field theory, self energy insertions on external legs have to be resummed separately to find the renormalized mass lll requires – separating graphs with self-energy insertions on external lines from other graphs – off-shell 2-point function to look for renormalized pole position String field theory is well suited for this task.