A Metaphysical and Linguistic Approach to Type Design and Typography Ivan Terestschenko Rocha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brand Style Guide.Indd

California Baptist University Brand Style Guide CALIFORNIA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY BRAND STYLE GUIDE The CBU Brand A brand is the personality a consumer creates for the organizations or products he or she interacts with. Consumers attribute characteristics to organizations to help themselves understand and then engage or avoid them. Brands can be hopeful, helpful, funny, tired, aloof or cold. Consumers create and revise brand personalities every time they come into contact with the organization. These interactions leave impressions on the consumer’s memory. Visualize the impression a branding iron leaves on the backside of a cow and you begin to appreciate the value of each of your interactions with students, parents, alumni, donors and friends. Consistency is essential to building and maintaining a strong brand for two reasons. First, consumers compare each new interaction to memories of previous interactions. When each successive interaction reinforces previous interactions, brand strength is increased. When interactions conflict with each other, the consumer is left thinking the brand is confused and weak. Second, competition for the consumer’s mind is fierce with organizations competing for milliseconds of their attention through a steady barrage of commercial messages. Consistency in CBU’s message and presentation improves the viewer’s (or listener’s) comprehension and increases the likelihood he or she will understand our message in the brief moment we have to communicate it to them. This guide has been developed to help every member of the CBU workforce (1) understand that he or she IS the CBU brand, and (2) properly and consistently represent the brand in all visual and verbal communications. -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

15 the Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia

The Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia LUZ RELLO and RICARDO BAEZA-YATES, Web Research Group, DTIC, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Around 10% of the people have dyslexia, a neurological disability that impairs a person’s ability to read and write. There is evidence that the presentation of the text has a significant effect on a text’s accessibility for people with dyslexia. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no experiments that objectively 15 measure the impact of the typeface (font) on screen reading performance. In this article, we present the first experiment that uses eye-tracking to measure the effect of typeface on reading speed. Using a mixed between-within subject design, 97 subjects (48 with dyslexia) read 12 texts with 12 different fonts. Font types have an impact on readability for people with and without dyslexia. For the tested fonts, sans serif , monospaced, and roman font styles significantly improved the reading performance over serif , proportional, and italic fonts. On the basis of our results, we recommend a set of more accessible fonts for people with and without dyslexia. Categories and Subject Descriptors: H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User Interfaces— Screen design, style guides; K.4.2 [Computers and Society]: Social Issues—Assistive technologies for per- sons with disabilities General Terms: Design, Experimentation, Human Factors Additional Key Words and Phrases: Dyslexia, learning disability, best practices, web accessibility, typeface, font, readability, legibility, eye-tracking ACM Reference Format: Luz Rello and Ricardo Baeza-Yates. 2016. The effect of font type on screen readability by people with Dyslexia. -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-6985 SMITH, Anna Laura, 1915- TWENTIETH CENTURY INTERPRETATIONS of the DON JUAN THEME

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

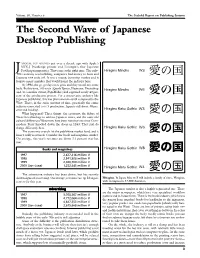

The Second Wave of Japanese Desktop Publishing

Volume 30, Number 6 The Seybold Report on Publishing Systems The Second Wave of Japanese Desktop Publishing APANESE DTP ARRIVED just over a decade ago with Apple’s NTX-J PostScript printer and Linotype’s first Japanese J PostScript imagesetter. They came at the right time: The early- ’90s economy was bubbling, companies had money to burn and Japanese DTP took off. It was a young, booming market and it forgave many mistakes that would haunt the industry later. By 1996, the go-go days were gone and they would not come back. By this time, DTP tools (Quark Xpress, Illustrator, Photoshop and, to a smaller extent, PageMaker) had captured nearly 40 per- cent of the production process. For a conservative industry like Japanese publishing, this was phenomenal—until compared to the West. There, in the same amount of time, practically the entire industry converted to DTP production. Japan is still about 40 per- cent and holding. What happened? Three things: the economy, the failure of Western technology to address Japanese issues, and the same old cultural differences Westerners have been running into since Com- modore Perry knocked down the doors in 1853. They just do things differently here. The economic crunch hit the publishing market hard, and it hasn’t really recovered. Consider the book and magazine market: On average, this year’s revenues are down 3.4 percent over last year. Books and magazines 1997 2,637,416 million ¥ 1998 2,541,508 million ¥ 1999 2,460,700 million ¥ 2000 (Jan–June) 1,232,445 million ¥ The advertising industry has been down, but has recently shown signs of recovering: On average, revenues are up 10.4 per- Hiragino. -

Tutorials Point, Simply Easy Learning

Tutorials Point, Simply Easy Learning UML Tutorial Tutorialspoint.com UNIX is a computer Operating System which is capable of handling activities from multiple users at the same time. Unix was originated around in 1969 at AT&T Bell Labs by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. This tutorial gives an initial push to start you with UNIX. For more detail kindly check tutorialspoint.com/unix What is Unix ? The UNIX operating system is a set of programs that act as a link between the computer and the user. The computer programs that allocate the system resources and coordinate all the details of the computer's internals is called the operating system or kernel. Users communicate with the kernel through a program known as the shell. The shell is a command line interpreter; it translates commands entered by the user and converts them into a language that is understood by the kernel. Unix was originally developed in 1969 by a group of AT&T employees at Bell Labs, including Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna. There are various Unix variants available in the market. Solaris Unix, AIX, UP Unix and BSD are few examples. Linux is also a flavour of Unix which is freely available. Several people can use a UNIX computer at the same time; hence UNIX is called a multiuser system. A user can also run multiple programs at the same time; hence UNIX is called multitasking. Unix Architecture: Here is a basic block diagram of a UNIX system: 1 | P a g e Tutorials Point, Simply Easy Learning The main concept that unites all versions of UNIX is the following four basics: Kernel: The kernel is the heart of the operating system. -

SWOT Analysis and Related Countermeasures for Croatia To

CIRR XXIII (78) 2017, 169-185 ISSN 1848-5782 UDC 379.8:910.4(497.5:510) Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, DOI 10.1515/cirr-2017-0012 XXIII (78) - 2017 SWOT Analysis and Related Countermeasures for Croatia to Explore the Chinese Tourist Source Market Wang Qian Abstract Croatia is a land endowed with rich and diversified natural and cultural tourist resources. Traveling around Croatia, I was stunned by its beauty. However, I noticed that there were few Chinese tourists in Croatia. How can we bring more Chinese tourists to Croatia? How can we make them happy and comfortable in Croatia? And, at the same time, how can we avoid polluting this tract of pure land? Based on first-hand research work, I make a SWOT analysis of the Chinese tourist source market of Croatia and put forward related countermeasures from the perspective of a native Chinese. The positioning of tourism in Croatia should be ingeniously packaged. I recommend developing diversified and specialized tourist products, various marketing and promotional activities, simple and flexible visa policies and regulations, and other related measures to further explore the Chinese tourist source market of Croatia. KEY WORDS: SWOT analysis, Croatia, Chinese tourist source market, sustainable tourism, direct flight 169 Introduction Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, XXIII (78) - 2017 I worked in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, for three years. During my stay, I walked almost all around Croatia. I travelled in Dalmatia for two weeks, visiting Zadar, Šibenik, Skradin, Trogir, Split, Hvar, Korčula and Dubrovnik. I toured Istria for a week, visiting Opatija, Pula, Rovinj and Poreč. -

Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) Fact Sheet The

Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) Fact Sheet . The Industrial Designers Society of America began in 1965 out of the merger of several organizations to include American Designers Institute (ADI), Industrial Designers Institute (IDI), Industrial Designers Education Association (IDEA), Society of Industrial Designers (SID) and American Society of Industrial Designers (ASID). IDSA’s core purpose is to advance the profession of industrial design through education, information, community and advocacy. IDSA creates value by . Publishing Innovation, a quarterly professional journal of industrial design practice and education in America . Developing and organizing a joint national conference and education symposium each year, which brings together industrial designers, educators, business executives and students from all over the world . Hosting five district conferences annually where design practitioners, educators and students gather to consider the state of the profession . Creating and conducting the annual International Design Excellence Awards® (IDEA) and distributing information on the winners to the business, general, international and US design media . Hosting a website to communicate with the industrial design community, to keep members informed and to provide a place for unique content and dialogue to share . Distributing designBytes email that highlights the latest news and trends in the design world . Providing statistical research studies on professional practice, and the structure and financing of consulting and corporate design organizations . Advocating for the industrial design community to federal agencies and state governments . Serving as the primary information resource on design for national newspapers, magazines and television networks . Acting as a clearinghouse for design information requested by the general public . To serve the interests and activities of its members, IDSA formed 16 special interest sections . -

JAF Herb Specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9

JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9 Designer: Tim Ahrens Format: Cross platform OpenType Styles & weights: Regular, Bold, Condensed & Bold Condensed Purchase options : OpenType complete family €79 Single font €29 JAF Herb Webfont subscription €19 per year Tradition ist die Weitergabe des Feuers und nicht die Anbetung der Asche. Gustav Mahler www.justanotherfoundry.com JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 2 of 9 Making of Herb Herb is based on 16th century cursive broken Introducing qualities of blackletter into scripts and printing types. Originally designed roman typefaces has become popular in by Tim Ahrens in the MA Typeface Design recent years. The sources of inspiration range course at the University of Reading, it was from rotunda to textura and fraktur. In order further refined and extended in 2010. to achieve a unique style, other kinds of The idea for Herb was to develop a typeface blackletter were used as a source for Herb. that has the positive properties of blackletter One class of broken script that has never but does not evoke the same negative been implemented as printing fonts is the connotations – a type that has the complex, gothic cursive. Since fraktur type hardly ever humane character of fraktur without looking has an ‘italic’ companion like roman types few conservative, aggressive or intolerant. people even know that cursive blackletter As Rudolf Koch illustrated, roman type exists. The only type of cursive broken script appears as timeless, noble and sophisticated. that has gained a certain awareness level is Fraktur, on the other hand, has different civilité, which was a popular printing type in qualities: it is displayed as unpretentious, the 16th century, especially in the Netherlands. -

307-151 Issue 1 N N~Nnwtsystem V ~ U~ U~ Release 2.0 DOCUMENTER's WORKBENCH™ Software 'Text Formatters Reference

December 1983 307-151 Issue 1 n n~nnWTsystem V ~ U~ U~ Release 2.0 DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCH™ Software 'Text Formatters Reference © 1983 Western Electric All Rights Reserved Printed in USA Western Electric ..... UNIX is a trademark of Bell Laboratories DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCH is a trademark of Western Electric CONTENTS Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Chapter 2 NROFF/TROFF TUTORIAL Chapter 3 NROFF AND TROFF USER MANUAL Chapter 4 DEVICE-INDEPENDENT TROFF Chapter 5 SROFF TUTORIAL GUIDE Chapter 6 SROFF REFERENCE MANUAL - I - Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION PAGE TEXT FORMATTERS ........................................... 1-1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION This book is a guide and reference manual for the text formatters that are provided with the UNIX* system DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCHt software. This software provides an integrated set of text processing tools for easy, flexible, and professional documentation production. Books that describe other aspects of the DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCH software are: • Introduction and Reference Manual-Select Code 307-150 • Macro Packages Reference-Select Code 307-152 • Preprocessors Reference-Select Code 307-153. The beginning user should refer to the DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCH software Introduction and Reference Manual for a better overall description of the text processing tools available on the UNIX system. TEXT FORMATTERS On the DOCUMENTER'S WORKBENCH software, the text formatting programs provide control of text format by the use of requests (sometimes called formatter primitives) that are mixed in with the text to be formatted. These requests normally consist of two lowercase letters preceded by a period, on a line by themselves in the text file. The request may be followed on the same line by numbers or letters that provide the formatter with more information about the function of the request.