Public Port Authority West Virginia Department of Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listed the Senate and House Education Committees Below Because That’S the Two We Most Often Deal With

Here is a link to the House roster where you will find contact information for House members: http://www.wvlegislature.gov/house/roster.cfm Here is a link to the Senate roster where you will find contact information for Senate members: https://www.wvlegislature.gov/senate1/roster.cfm Please make sure you are familiar with your local legislators as well as those in leadership positions. The new directory is available on the legislative site. I listed the Senate and House Education Committees below because that’s the two we most often deal with. WEST VIRGINIA STATE SENATE LEADERSHIP SENATE PRESIDENT— CRAIG P. BLAIR PREIDENT PRO TEMPORE – DONNA BOLEY MAJORITY LEADER – TOM TAKUBO MAJORITY WHIP – RYAN W. WELD MINORITY LEADER – STEPHEN BALDWIN MINORITY WHIP – MICHAEL WOELFEL SENATE EDUCATION COMMITTEE Patricia Rucker - Chair Robert Karnes - Vice Chair Azinger, Beach, Boley, Clements, Grady, Plymale, Roberts, Romano, Stollings, Tarr, Trump, Unger SENATE FINANCE Eric Tarr - Chair Dave Sypolt - Vice Chair Baldwin, Boley, Clements, Hamilton, Ihlenfeld, Jeffries, Maroney, Martin, Nelson, Plymale, Roberts, Stollings, Swope, Takubo, Unger SENATE DISTRICT - 01 William Ihlenfeld (D - Ohio) Ryan Weld (R - Brooke) SENATE DISTRICT - 02 Michael Maroney (R - Marshall) Charles Clements (R - Wetzel) SENATE DISTRICT - 03 Donna Boley (R - Pleasants) Michael Azinger (R - Wood) SENATE DISTRICT - 04 Amy Grady (R - Mason) Eric Tarr (R - Putnam) SENATE DISTRICT - 05 Robert Plymale (D - Wayne) Michael Woelfel (D - Cabell) SENATE DISTRICT - 06 Chandler Swope (R - Mercer) -

April 2016 Magazine.Indd

Farm Bureau News April 2016 Primary Election Endorsements Issue bytes Communications Boot Camp Caterpillar Adds New Teaches Women How to Tell Machines, Tools to Farm Ag’s Story Bureau Member Discount Farm Bureau members can now save up to The American Farm Bureau Federation is $2,500 thanks to the addition of hydraulic excavators now accepting applications for its tenth Women’s and a medium track-type tractor to the Caterpillar Communications Boot Camp class, July 12 –15 in Member Benefi t program. In addition, Farm Bureau Washington, D.C. The three-day intensive training is members will now receive a $250 credit on work tool open to all women who are Farm Bureau members. attachments purchased with a new Caterpillar machine. The program focuses on enhancing communication and leadership skills and includes targeted training “Caterpillar is excited to grow its partnership with in the areas of public speaking, media relations, Farm Bureau by offering discounts on additional messaging and advocacy. products,” says Dustin Johansen, agriculture segment manager for Caterpillar. “Our goal is always to help Fifteen women will be selected to participate in members be more productive and better serve Farm this year’s program. Applications are available online Bureau members’ diverse needs.” or through state Farm Bureaus. The deadline for submissions is May 10. All applicants will be notifi ed “West Virginia Farm Bureau is proud to make of their status by June 1. these exclusive benefi ts available to our members,” says Charles Wilfong, president of West Virginia The American Farm Bureau Women’s Leadership Farm Bureau. -

W.Va. Chamber PAC Endorses Bill Cole for Governor

For Immediate Release: Contact: Steve Roberts Tuesday, September 27, 2016 (304) 342-1115 W.Va. Chamber PAC Endorses Bill Cole for Governor Charleston, W.Va. – The West Virginia Chamber Political Action Committee today announced its endorsement of Bill Cole for Governor of West Virginia. Bill Cole has served as the President of the West Virginia Senate since 2015. West Virginia Chamber President Steve Roberts stated, “Bill Cole works tirelessly to promote job creation and economic development in West Virginia. Under his leadership, the West Virginia Legislature has begun the most comprehensive series of job creation reforms in a lifetime. His leadership in the Governor’s Office will allow West Virginia to embark on a new era fueled by Bill Cole’s energy, enthusiasm and expertise.” The Chamber PAC, which announced the endorsements, is the political arm of the West Virginia Chamber of Commerce, which is the state’s leading association of employers whose priority is job creation and economic development. Chamber members employ over half of West Virginia’s workforce. Roberts continued, “We listen carefully to our members for guidance, and they have clearly and overwhelmingly indicated their support for Bill Cole to be the next Governor of West Virginia.” During the two legislative sessions in which Bill Cole served as President of the Senate, the Legislature enacted legislation to: . support small businesses . promote good health initiatives . guarantee legal fairness and removed partisanship from our state’s courts . implement regulatory reforms that protect public health while encouraging businesses to grow a create jobs . undertake significant education and workforce preparedness measures . -

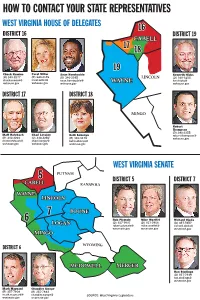

E Introduced 2017 Regular Legislative Session

WEB EXTRA For local news coverage 24-7, Monday, February 13, 2017 3A check www.herald-dispatch.com. Local Questions? Call 304-526-2799 CITY COUNCIL Fourteen represent Cabell, Wayne Ordinance to counties in West Virginia Legislature CHARLESTON — More resenting southwestern West have a 22-member majority, fix road slips to than 130 legislators from Virginia citizens’ voice at the and 12 Democrats represent the throughout the Mountain State capitol for the next 60 days. minority party in the chamber. made their way to Charleston Both chambers of the West Below is a listing of local leg- last week for the start of the Virginia Legislature have islators’ contact information at be introduced 2017 regular legislative session. Republican majorities. the West Virginia State Capitol. Among them are eight mem- The GOP has a 63-mem- FoR more information about By JOSEPHINE MENDEZ limit at $3.5 million and would bers of the House of Delegates ber majority to Democrats’ members of the West Virginia The Herald-Dispatch be financed using the monthly [email protected] $7.15 Water Quality Service and six members of the Sen- 36-member minority, along Legislature, visit www.legis. HUNTINGTON — Two Fee, which was implemented ate who represent portions of with one delegate with no party state.wv.us. Huntington Stormwater Util- October 2014. ity projects that have been at a There will be no new fees Cabell and Wayne counties affiliation. standstill for more than a year imposed with this ordinance, and will be responsible for rep- In the Senate, Republicans —The Herald-Dispatch could soon be moving forward. -

08 Wv History Reader Fain.Pdf

Early Black Migration and the Post-emancipation Black Community in Cabell County,West Virginia, 1865-1871 Cicero Fain ABSTRACT West Virginia’s formation divided many groups within the new state. Grievances born of secession inflamed questions of taxation, political representation, and constitutional change, and greatly complicated black aspirations during the state’s formative years. Moreover, long-standing attitudes on race and slavery held great sway throughout Appalachia. Thus, the quest by the state’s black residents to achieve the full measure of freedom in the immediate post-Civil War years faced formidable challenges.To meet the mandates for statehood recognition established by President Lincoln, the state’s legislators were forced to rectify a particularly troublesome conundrum: how to grant citizenship to the state’s black residents as well as to its former Confederates. While both populations eventually garnered the rights of citizenship, the fact that a significant number of southern West Virginia’s black residents departed the region suggests that the political gains granted to them were not enough to stem the tide of out-migration during the state’s formative years, from 1863 to 1870. 4 CICERO FAIN / EARLY BLACK MIGRATION IN CABELL COUNTY ARTICLE West Virginia’s formation divided many groups within the new state. Grievances born of secession inflamed questions of taxation, political representation, and constitutional change, and greatly complicated black aspirations during the state’s formative years. It must be remembered that in 1860 the black population in the Virginia counties comprising the current state of West Virginia totaled only 5.9 percent of the general population, with most found in the western Virginia mountain region.1 Moreover, long-standing attitudes on race and slavery held great sway throughout Appalachia. -

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 By Catherine B. Enomoto1, James L. Coleman, Jr.1, John T. Haynes2, Steven J. Whitmeyer2, Ronald R. McDowell3, J. Eric Lewis3, Tyler P. Spear3, and Christopher S. Swezey1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA 20192 2 James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA 22807 3 West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV 26508 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

The Weather and Climate of West Virginia

ISTOCKPHOTO/CARROLLMT West Virginia by Dr. Kevin T. Law and H. Michael Mogil The Tibbet Knob overlook in George Washington National Forest. est Virginia is a geographically moves a direct Atlantic Ocean influence from its small state that only covers about weather and climate and ensures that the state’s 24,000 square miles. However, climate is more continental than maritime. The due to two distinct two pan- Allegheny Mountains run north to south along Whandles that protrude to the north and east, the the Virginia border and are largely responsible for state’s dimensions are actually 200 miles square. the state’s east-to-west climatological changes. The northern tip extends farther north than The highest point in the state, Spruce Knob, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, while the eastern tip has an elevation of 4,863 feet above sea level. is only 60 miles from Washington, D.C. In ad- In fact, the mean elevation in the state is about dition, the southernmost point is farther south 1,500 feet, which is the highest for any state east than Richmond, Virginia, while the westernmost of the Mississippi River. This is more than 500 point is farther west than Port Huron, Michigan. feet higher than Pennsylvania, the second high- The unusual shape and location of the state has est mean elevation for a state. The topography coined the phrase, “West Virginia is the most varies greatly by county, with some individual southern of the northern states, the most north- counties exhibiting elevation changes of more ern of the southern states, and the most western than 3,000 feet. -

State Senate Recorded Votes

West Virginia AFL-CIO 2013 Committee on Political Education - COPE Senate Voting Record No Senate Votes Recorded for 2013 (D): Democrat, (R): Republican – R: Right, W: Wrong, A: Absent, E: Excused, a: abstained Name in Bold: COPE Endorsed in the most recent election. Accumulative DISTRICT - SENATOR - COUNTY TOTAL Next Election R W A SD 1 - Rocky Fitzsimmons (D) Ohio 2014 - - - SD 1 - Jack Yost (D) Brooke 2016 20 0 2 SD 2 - Larry Edgell (D) Wetzel 2014 17 7 0 SD 2 - Jeff Kessler (D) Marshall 2016 22 4 0 SD 3 - Donna Boley (R) Pleasants 2016 15 43 0 SD 3 - David Nohe (R) Wood 2014 0 3 0 SD 4 - Mitch Carmichael (R) Jackson 2016 9 27 4 SD 4 - Mike Hall (R) Putnam 2014 12 36 1 SD 5 - Evan Jenkins (D) Cabell 2014 20 17 0 SD 5 - Robert H. Plymale (D) Wayne 2016 19 18 0 SD 6 - H. Truman Chafin (D) Mingo 2014 53 26 1 SD 6 - Bill Cole (R) Mercer 2016 - - - SD 7 - Ron Stollings (D) Boone 2014 5 2 0 SD 7 - Art Kirkendoll (D) Logan 2016 - - - Accumulative DISTRICT - SENATOR - COUNTY TOTAL Next Election SD 8 - Chris Walters (R) Kanawha 2016 - - - SD 8 - Erik Wells (D) Kanawha 2014 3 5 1 SD 9 - Daniel Hall (D) Wyoming 2016 13 2 0 SD 9 - Mike Green (D) Raleigh 2014 4 3 2 SD 10 - Ronald Miller (D) Greenbrier 2014 2 1 0 SD 10 - William Laird (D) Fayette 2016 14 3 0 SD 11 - Clark Barnes (R) Randolph 2016 4 7 0 SD 11 - Gregory Tucker (D) Nicholas 2014 2 1 0 SD 12 - Sam Cann (D) Harrison 2014 29 30 5 SD 12 - Douglas Facemire (D) Braxton 2016 4 2 0 SD 13 - Robert Beach (D) Monongalia 2014 21 16 0 SD 13 - Roman Prezioso (D) Marion 2016 36 18 3 SD 14 - Bob Williams -

Chapter 37 of Title 2.2 the Virginia Freedom of Information Act (Effective July 1, 2021)

Chapter 37 of Title 2.2 The Virginia Freedom of Information Act (Effective July 1, 2021) 2.2-3700. Short title; policy 2.2-3701. Definitions 2.2-3702. Notice of chapter 2.2-3703. Public bodies and records to which chapter inapplicable; voter registration and election records; access by persons incarcerated in a state, local, or federal correctional facility 2.2-3703.1. Disclosure pursuant to court order or subpoena 2.2-3704. Public records to be open to inspection; procedure for requesting records and responding to request; charges; transfer of records for storage, etc. 2.2-3704.01. Records containing both excluded and nonexcluded information; duty to redact 2.2-3704.1. Posting of notice of rights and responsibilities by state and local public bodies; assistance by the Freedom of Information Advisory Council 2.2-3704.2. Public bodies to designate FOIA officer 2.2-3704.3. Training for local officials 2.2-3705. Repealed 2.2-3705.1. Exclusions to application of chapter; exclusions of general application to public bodies 2.2-3705.2. Exclusions to application of chapter; records relating to public safety 2.2-3705.3. Exclusions to application of chapter; records relating to administrative investigations 2.2-3705.4. Exclusions to application of chapter; educational records and certain records of educational institutions 2.2-3705.5. Exclusions to application of chapter; health and social services records 2.2-3705.6. (Effective until October 1, 2021) Exclusions to application of chapter; proprietary records and trade secrets 2.2-3705.6. (Effective October 1, 2021, until January 1, 2022) Exclusions to application of chapter; proprietary records and trade secrets 2.2-3705.6. -

Volume 23 No 11 November 2014

Volume 23, Number 11 • November 2014 A PUBLICATION OF THE AFFILIATED CONSTRUCTION TRADES A Division of the WV State Building Trades, AFL-CIO | Bill Hutchinson, President | Dave Efaw, Secretary-Treasurer | Steve White, Director Republicans to Control State House and Senate What to expect? Expect the worst. “Not this time,” said Efaw. “We Th e passages of so-called Right- area for construction wages and ben- With republican control of both expect to see votes on the so-called to-Work laws undermine a union’s efi ts and prevents low wage competi- the House of Delegates and the Sen- Right-to-Work legislation which is ability to exist. tion. ate in West Virginia many people are aimed directly at destroying labor In essence a person has the right Numerous studies show taxpay- wondering what to expect in the up- unions.” to enjoy all the benefi ts of a union ers benefi t from the system because coming session. In addition Efaw predicts the contract but does not have to pay the end price for projects remains the “Expect the worst,” said Dave state’s prevailing wage law will come dues. same with or without prevailing wage Efaw, Secretary-Treasurer of the WV under attack in many ways. Th e eff ect in every state where it laws. State Building Trades. “We will likely see bills to com- has passed is to erode union strength Workers in prevailing wage states “We will try to work with republi- pletely repeal the law, and perhaps over time which leads to lower wages becomes more productive, have a can leaders to fi nd compromises but some bills to change how wages are and benefi ts. -

Current Office Holders

Federal Name Party Office Term Next Election Joe Biden Democrat U.S President 4 Years 2024 Kamala Harris Democrat U.S. Vice President 4 Years 2024 Joe Manchin Democratic U.S. Senate 6 Years 2024 Shelley Moore Capito Republican U.S. Senate 6 Years 2026 David McKinley Republican U.S House, District 1 2 Years 2022 Alexander Mooney Republican U.S. House, District 2 2 Years 2022 Carol Miller Republican U.S. House, District 3 2 Years 2022 State Name Party Office Term Next Election Jim Justice Republican Governor 4 Years 2024 Mac Warner Republican West Virginia Secretary of State 4 Years 2024 John "JB" McCuskey Republican West Virginia State Auditor 4 Years 2024 Riley Moore Republican West Virginia State Treasurer 4 Years 2024 Patrick Morrisey Republican Attorney General of West Virginia 4 Years 2024 Kent Leonhardt Republican West Virginia Commissioner of Agriculture 4 Years 2024 West Virginia State Senate Name Party District Next election Ryan W. Weld Republican 1 2024 William Ihlenfeld Democrat 1 2022 Mike Maroney Republican 2 2024 Charles Clements Republican 2 2022 Donna J. Boley Republican 3 2024 Mike Azinger Republican 3 2022 Amy Grady Republican 4 2024 Eric J. Tarr Republican 4 2022 Robert H. Plymale Democrat 5 2024 Mike Woelfel Democrat 5 2022 Chandler Swope Republican 6 2024 Mark R Maynard Republican 6 2022 Rupie Phillips Republican 7 2024 Ron Stollings Democrat 7 2022 Glenn Jeffries Democrat 8 2024 Richard Lindsay Democrat 8 2022 David Stover Republican 9 2024 Rollan A. Roberts Republican 9 2022 Jack Woodrum Republican 10 2024 Stephen Baldwin Democrat 10 2022 Robert Karnes Republican 11 2024 Bill Hamilton Republican 11 2022 Patrick Martin Republican 12 2024 Mike Romano Democrat 12 2022 Mike Caputo Democrat 13 2024 Robert D. -

2020 COPE Voting Record.Pdf

West Virginia AFL-CIO Committee on Political Education (COPE) State Senate - 2020 Recorded Votes ISSUE #1 - SB 285 – ELIMINATING WV GREYHOUND BREEDING DEVELOPMENT FUND Description/Action: Job killing legislation for greyhound tracks in Wheeling and Cross Lanes. Voting Body: 34-member Senate - The Vote: Third Reading - RCS #180 – SEQ. NO. 0180. – February 19, 2020 – 12:21PM YEAS: 11 - NAYS: 23 - NOT VOTING: 0-Absent / A NAY VOTE IS CONSIDERED RIGHT BY LABOR ISSUE #2 - SB 528 – CREATING UNIFORM WORKER CLASSIFICATION ACT Description/Action: Legislation that would create a contract worker classification – The bill would make it too easy for an employer to call an employee - an independent contractor. If this happened, no payroll taxes would be paid by the employer, which would include Social Security, Unemployment and Workers Comp. The employee – who would no longer be an employee – would be responsible. Bad legislation! Voting Body: 34-member Senate - The Vote: Third Reading - RCS #225 – SEQ. NO. 0225. – February 24, 2020 - 12:17PM YEAS: 17 - NAYS: 16 - NOT VOTING: 1-Absent / A NAY VOTE IS CONSIDERED RIGHT BY LABOR ISSUE #3 - HB 4155 – SUPERVISION OF PLUMBING WORK Description/Action: Relating generally to the regulation of plumbers – Adding a Drug Testing requirement. Voting Body: 34-member Senate - The Vote: Second Reading-Amendment to Amendment – RCS #526 – SEQ. NO. 0526. – March 6, 2020 - 5:08PM YEAS: 16 - NAYS: 18 - NOT VOTING: 0-Absent / A NAY VOTE IS CONSIDERED WRONG BY LABOR ISSUE #4 - HB 4155 – SUPERVISION OF PLUMBING WORK Description/Action: Relating generally to the regulation of plumbers – Requiring E-Verify be used.