Hotel Sorrento

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2013 Annual Report 2013

Annual Report 2013 Annual Report 2013 4 Objectives and Mission Statement 50 Open Door 6 Key Achievements 9 Board of Management 52 Literary 10 Chairman’s report Literary Director’s Report 12 Artistic Director’s report MTC is a department of the University of Melbourne 14 Executive Director’s report 54 Education 16 Government Support Education Manager’s Report and Sponsors 56 Education production – Beached 18 Patrons 58 Education Workshops and Participatory Events 20 2013 Mainstage Season MTC Headquarters 60 Neon: Festival of 252 Sturt St 22 The Other Place Independent Theatre Southbank VIC 3006 24 Constellations 03 8688 0900 26 Other Desert Cities 61 Daniel Schlusser Ensemble 28 True Minds 62 Fraught Outfit Southbank Theatre 30 One Man, Two Guvnors 63 The Hayloft Project 140 Southbank Blvd 32 Solomon and Marion 64 THE RABBLE Southbank VIC 3006 34 The Crucible 65 Sisters Grimm Box Office 03 8688 0800 36 The Cherry Orchard 66 NEON EXTRA 38 Rupert mtc.com.au 40 The Beast 68 Employment Venues 42 The Mountaintop Actors and Artists 2013 Throughout 2013 MTC performed its Melbourne season of plays at the 70 MTC Staff 2013 Southbank Theatre, The Sumner and The Lawler, 44 Add-on production and the Fairfax Studio and Playhouse at The Book of Everything 72 Financial Report Arts Centre Melbourne. 74 Key performance indicators 46 MTC on Tour: 76 Audit certificate Managing Editor Virginia Lovett Red 78 Financial Statement Graphic Designer Emma Wagstaff Cover Image Jeff Busby 48 Awards and nominations Production Photographers Jeff Busby, Heidrun Löhr Cover -

Company B ANNUAL REPORT 2008

company b ANNUAL REPORT 2008 A contents Company B SToRy ............................................ 2 Key peRFoRmanCe inDiCaToRS ...................... 30 CoRe ValueS, pRinCipleS & miSSion ............... 3 FinanCial Report ......................................... 32 ChaiR’S Report ............................................... 4 DiReCToRS’ Report ................................... 32 ArtistiC DiReCToR’S Report ........................... 6 DiReCToRS’ DeClaRaTion ........................... 34 GeneRal manaGeR’S Report .......................... 8 inCome STaTemenT .................................... 35 Company B STaFF ........................................... 10 BalanCe SheeT .......................................... 36 SeaSon 2008 .................................................. 11 CaSh Flow STaTemenT .............................. 37 TouRinG ........................................................ 20 STaTemenT oF ChanGeS in equiTy ............ 37 B ShaRp ......................................................... 22 noTeS To The FinanCial STaTements ....... 38 eDuCaTion ..................................................... 24 inDepenDenT auDiT DeClaRaTion CReaTiVe & aRTiSTiC DeVelopmenT ............... 26 & Report ...................................................... 49 CommuniTy AcceSS & awards ...................... 27 DonoRS, partneRS & GoVeRnmenT SupporteRS ............................ 28 1 the company b story Company B sprang into being out of the unique action taken to save Landmark productions like Cloudstreet, The Judas -

Belvoir Annual Report 2015

Belvoir Annual Report 2015 A Contents This Is Our Company 02 Core Values, Principles and Mission 03 Chair’s Report 04 Artistic Director’s Report 06 Incoming Artistic Director’s Report 08 Executive Director’s Report 10 2015 Season and Tours 12 Co-producer’s Season 25 National & International Touring 27 Education 32 Artistic and Programming 36 Development 38 Donors 40 Board and Staff 42 Financial Statements 47 Key Performance Indicators 48 Directors’ Report 50 Directors’ Meetings 54 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 54 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 55 Statement of Financial Position 56 Statements of Changes in Equity and Cash Flows 57 Notes to the Financial Statements 58 Directors’ Declaration 68 Auditor’s Report 69 Partners, Sponsors and Supporters 70 BMiranda Tapsell & Leah Purcell in Radiance. Photo: Brett Boardman. This Is Our Company OUR Core Values and Principles One building. • Belief in the primacy of the artistic process Six hundred people. • Clarity and playfulness in storytelling Endless stories. • A sense of community within the theatrical environment When the theatre in an old tomato sauce Belvoir’s position as one of Australia’s • Responsiveness to current social and political issues factory at 25 Belvoir Street was threatened most innovative and acclaimed theatre • Equality, ethical standards and shared ownership of with redevelopment in 1984, more than companies has been assured by such artistic and company achievements 600 people – passionate lovers and makers landmark productions as The Glass of theatre – formed a syndicate to buy Menagerie, Angels in America, The Wild • Development of our performers, artists and staff the building and save it. -

The Seed.Pdf

KATE MULVANY is an award-winning playwright and screenwriter. Her new play, The Rasputin Affair, was shortlisted for the Griffin New Play Award and the Patrick White Award and will premiere at Ensemble Theatre in 2017. Jasper Jones, her adaptation of Craig Silvey’s novel, premiered at Belvoir in 2016 to a sell out season and was subsequently produced by Melbourne Theatre Company that same year. It returned to Belvoir in 2017 to another sell-out season. In 2015, she penned Masquerade, a reimagining of the much-loved children’s book by Kit Williams, which was performed at the 2015 Sydney Festival, the State Theatre Company of South Australia and the Melbourne Festival. Her autobiographical play, The Seed, commissioned by Belvoir, won the Sydney Theatre Award for Best Independent Production in 2007 and is currently being developed into a feature film. Kate’s Medea, created with Anne-Louise Sarks and produced by Belvoir in 2012, won a number of awards including an AWGIE and five Sydney Theatre Awards. It completed hugely successful seasons at London’s Gate Theatre and Auckland’s Silo Theatre. She’s also currently under commission at Sydney Theatre Company. Kate’s other plays and musicals include The Danger Age (Deckchair Theatre/La Boite); Blood and Bone (The Stables/Naked Theatre Company); The Web (Hothouse/Black Swan State Theatre Company); Somewhere (co-written with Tim Minchin for the Joan Sutherland PAC); and Storytime (Old Fitzroy Theatre), which won Kate the 2004 Philip Parsons Award. Kate is also an award-winning stage and screen actor, whose credits include The Seed, Buried Child (Belvoir); Blasted (B Sharp/ Sheedy Productions); Tartuffe, Macbeth, Julius Caesar (Bell Shakespeare); The Crucible, Proof, A Man With Five Children, King Lear, Rabbit (Sydney Theatre Company); The Beast (Melbourne Theatre Company); The Literati, Mr Bailey’s Minder (Griffin Theatre Company); and the feature films The Little Death and The Great Gatsby. -

Year Play Author Director Cast Venue Dates Aust Premiere 1960 the Man Dinelli, Mel Hayes Gordon Lorraine Bayly, Kevin Dalton, Jo

Year Play Author Director Cast Venue Dates Aust Premiere 1960 The Man Dinelli, Mel Hayes Gordon Lorraine Bayly, Kevin Dalton, Jon Ewing, ENS 7/1/60-19/3/60 AP Guinea Gordon, Clarissa Kaye, Don Newland, Don Reid, Kylie Stewart, Anthony Wickert 1960 Orpheus Williams, Hayes Gordon David Crocker, Kevin Dalton, Gary ENS 31/3/60-2/7/60 AP Descending Tennesee Deacon, Jon Ewing, Lisle Harsant, Patricia Johnson, Patricia Jones, Clarissa Kaye, Sophie Krantz, Robin Lawlor, Reg Livermore, Marie Lorraine, Jerry Luke, Beverley McLeod, Frank Nolan, Jack Quinlan, Don Reid, Gary Shearston, Breck Stewart, Kylie Stewart, Sandra Stewart 1960 The Drunkard Smith, W H Hayes Gordon Victoria Anoux, Lorraine Bayly, Anna 23/7/60-4/2/61 AP Berner, J. Brown, L. Celi, Roie Cook, Kevin Dalton, Gary Deacon, John Denison, Jon Ewing, Joanna Franklin, Patricia Johnson, Patricia Jones, J.J., Judy King, Robin Lawlor, Reg Livermore, Jerry Luke, Ron Owen, William Pringle, James Scullin, Gary Shearston, Breck Stewart, Kylie Stewart, Sandra Stewart, Brian Young 1961 The Double Congreve, William Jon Ewing & Reg Victoria Anoux, Kevin Dalton, Jon Ewing, ENS 7/2/61-4/3/61 AP Dealer Livermore Mr. Henning, Patricia Johnson, Patricia Jones, Jan Kehoe, Reg Livermore, William Pringle, Les Shaw, Breck Stewart, Bryan Syron, Tony Wickert, Brian Young 1961 Miss Lonely Teichman, Howard Hayes Gordon Jan Avery, Henry Banister, Lorraine ENS 15/3/61-17/6/61 AP Hearts Bayly, Julie Collins, Roie Cook, John Dennis, Bettye Eister, Joan Franklin, Jone Hull, J.J., Patricia Jones, Reg Livermore, Anne -

Openbook Summer 2020

Bri Lee & Kate Mulvany Rick Morton’s Teela May Reid centre stage first fiction here & now SUMMER 2020 SUMMER 2020 SELF PORTRAIT WORDS Cathy Perkins Auburn Gallipoli Mosque General Manager Ergun Genel prays alone due to the coronavirus on the first day of Ramadan, Auburn Gallipoli Mosque, Sydney, NSW, 24 April 2020, photo by Kate Geraghty, Sydney Morning Herald Featured in the Photos1440 exhibition at the State Library of NSW, 16 January to 18 April 2021 SUMMER 2020 Openbook is designed and printed on the traditional and ancestral lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. The State Library of NSW offers our respect to Aboriginal Elders past, present and future, and extends that respect to other First Nations people. We celebrate the strength and diversity of NSW Aboriginal cultures, languages and stories. Enjoy a sneak peek of some of the highlights in the beautiful new Map Rooms in the Mitchell Building, page 22 22 Contents Features 10 Self-portrait 50 Drawing to a close Vivian Pham Sarah Morley 12 Staging Kate 54 The spreading Bri Lee fire of fake news Margaret Van Heekeren 20 New territory for maps Steve Meacham 94 Interview Teela May Reid 24 Tall & trimmed Mark Dapin 28 Photo essay — A year like no other 44 Coming out in the 70s Ashleigh Synnott 4 / OPENBOOK : Summer 20 38 70 78 86 Fiction Articles Regulars 38 The contestant 49 Sense of wonder 6 News & notes Rick Morton Bruce Carter 18 Take 5 — Spectacles 64 So you want to be 60 Community Poetry a poet — Street libraries 68 A writer’s guide: Penelope Nelson POC edition 82 Reviews -

The Literati by Justin Fleming After Molière's Les Femmes

GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY AND BELL SHAKESPEARE PRESENT THE LITERATI BY JUSTIN FLEMING AFTER MOLIÈRE’S LES FEMMES SAVANTES 27 MAY-16 JULY Director Lee Lewis Designer Sophie Fletcher Co-Composers & Sound Designers Max Lambert and Roger Lock Lighting Designer Verity Hampson With Caroline Brazier, Gareth Davies, Kate Mulvany, Jamie Oxenbould, Miranda Tapsell We live in an age of spin. And so did Molière. The spin doctors may change in wardrobe, manners or language, but they remain a rich field for biting satire. That the learned fool is more of a fool than an ignorant one remains as much a conundrum for us in the 21st century as it did for audiences in the 17th. Molière wrote on the threshold of the Age of Reason, so any spin that amounted to nonsense on stilts was both repugnant and laughable. I think Molière’s work is principally about extremes. Such human forces as love, passion, honesty, health, money, authority and religion (even if it is an obsession with books) are better lived in the moderate zones. As soon as we traverse that corridor, especially if we try to drag everyone else with us, we are on the PLAYWRIGHT’S NOTE path to the destruction of happiness. The Literati is many things, not least a piss-take on pretentious literary conceit, and as I approached the work, I always kept in mind some of the gushing DIRECTOR’S hyperbole that passes for writers’ festivals and book Molière at Griffin. Qu’est-ce que c’est? clubs both on television and off. In this vein, the play had Griffin, the only theatre company in the a modern resonance, which I was eager to capture. -

Minnie & Liraz

MINNIE & LIRAZ by Lally Katz Welcome At the beginning of every play’s rehearsal period we feel a great sense of excitement, but never more so than when it’s a world premiere of a new Australian work. In the case of Minnie & Liraz, it’s both a new Australian play and a truly Melbourne story, and I am thrilled that it’s Melbourne’s audiences who get to see its first presentation in the world. Minnie & Liraz has humour, honesty, warmth and imagination in spades, taking its audience on a wild and unpredictable ride. So strap yourselves in for some delicious twists and turns! Written by the inimitable Lally Katz and directed by Anne-Louise Sarks, this production brings together a wonderful team of actors and creative artists along with a little slice of Caulfield to MTC’s home in the Arts Centre – the Fairfax Studio. Throughout May, MTC’s stages are filled with three brand new Australian plays – Three Little Words, Melbourne Talam and Minnie & Liraz. They are three very different stories, but each a wonderful example of the work of the unique and talented writers we have in this country. MTC has a long history of working with and supporting local writers and our commitment remains as steadfast as ever. It fills me with immense pride that Melbourne audiences continue to echo this support by being such great advocates for new works, so thank you and I hope you enjoy this world premiere production. See you at the theatre! Brett Sheehy ao Artistic Director GET SOCIAL WITH MTC MelbourneTheatreCompany melbtheatreco melbtheatreco MTC.COM.AU Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors past and present, and to our shared future. -

STC Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Sydney Theatre Company acknowledges the Gadigal people and Bidjigal people of the Eora Nation who are the traditional custodians of the land on which the company gathers. We pay our respects to elders past, present and emerging, and we extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with whom we work and with whom we share stories. Aims of the Company “To provide first class theatrical entertainment for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun. That entertainment should reflect the society in which we live thus providing a point of focus, a frame of reference, by which we come to understand our place in the world as individuals, as a community and as a nation.” Richard Wherrett, 1980 Founding Artistic Director 2 3 Cover: (From centre right) Rose Riley, Ben O’Toole, Benedict Hardie and Contessa Treffone in The Harp in the South. Photo: Daniel Boud Rose Riley and Guy Simon in The Harp in the South. Photo: Daniel Boud 2018 in Numbers 214% 30,031 PEOPLE SAW AN 7,648 4 000 STC 724 SHOW 323,475 AND 160 OF PROGRAM TIX PERFORMANCES WORLD PREMIERE TIX TEACHERS PAID GLOBALLY 63% AUSTRALIAN PLAYS OUTSIDE & ADAPTATIONS ATTENDEES OF SYDNEY TO STC PRODUCTIONS IN 2018 1,449 WORLD 28 9 PREMIERES AWARDS 30 13 PARTICIPANTS IN CONNECTED: ADULT PLAYWRIGHTS 200 LANGUAGE LEARNING 12 ON COMMISSION WON THROUGH DRAMA PROGRAM 2 3 Chair’s Report IAN NAREV 2018 was a year of intense activity at Sydney Theatre Company, as we artistic momentum that STC has built up over years with artists and corporate partners who support us year after year. -

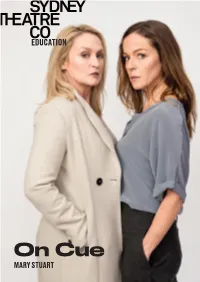

On Cue Mary Stuart.Indd

EDUCATION On Cue MARY STUART Table of Contents About On Cue and STC 2 Curriculum Connections 3 Cast and Creatives 4 Th e Playwright in Conversation 5 Synopsis/Context 6 Context & History 7 Character Analysis 8 Style 13 Th emes and Ideas 14 Elements of Production 19 Reference List 20 Compiled by Jacqui Cowell. Th e activities and resources contained in this document are designed for educators as the starting point for developing more comprehensive lessons for this production. Jacqui Cowell is the Education Projects Offi cer for the Sydney Th eatre Company. You can contact Jacqui on jcowell@sydneytheatre. com.au. © Copyright protects this Education Resource. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means in prohibited. How ever, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. 1 About On Cue and STC ABOUT ON CUE ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY STC Ed has a suite of resources located on our website to In 1980, STC’s fi rst Artistic Director Richard Wherrett enrich and strengthen teaching and learning surrounding defi ned STC’s mission as to provide “fi rst class theatrical the plays in the STC season. entertainment for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun.” Each school show will be accompanied by an On Cue e-publication which will feature essential information for Almost 40 years later, that ethos still rings true. teachers and students, such as curriculum links, information about the playwright, synopsis, character analysis, thematic STC off ers a diverse program of distinctive theatre of vision analysis and suggested learning experiences. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2015 September 2015 State Theatre Company of South Australia Adelaide Railway Station Station Road ADELAIDE SA 5000 PO Box 8252 Station Arcade ADELAIDE SA 5000 P: (08) 8415 5333 F: (08) 8231 6310 E: [email protected] W: www.statetheatrecompany.com.au ABN 55 386 202 154 CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL ....................................................................................................................... 4 CHAIR’S REPORT ....................................................................................................................................... 5 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT 2014 / 2015 .......................................................................................... 9 COMPANY OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 15 ORGANISATIONAL CHART ..................................................................................................................... 16 STATE THEATRE COMPANY BOARD .................................................................................................... 17 COMPANY MISSION, VISION AND STRATEGIC PLANNING ................................................................. 18 ARTISTIC VISION ...................................................................................................................................... 18 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT (AT 30 JUNE 2015) .................................................................... -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2010

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2010 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY 2010 Annual Report 1 Sydney Theatre Company Limited Pier 4, Hickson Road, Walsh Bay New South Wales 2000 Sydney Theatre Company PO Box 777, Millers Point New South Wales 2000 Administration Telephone +61 2 9250 1700 Facsimile +61 2 9251 3687 Email [email protected] Box Office Telephone +61 2 9250 1777 sydneytheatre.com.au Venues The Wharf Wharf 1 and Wharf 2 Pier 4, Hickson Road Walsh Bay Established in 1978, Sydney Theatre Company is one of Sydney Theatre Australia’s leading arts organisations and one of the busiest 22 Hickson Road Walsh Bay theatre companies in the world. From its home base at The Wharf in the burgeoning Walsh Bay Drama Theatre cultural precinct of Sydney, the Company produces a diverse Sydney Opera House range of works seen by in excess of 300,000 people each year. It performs in The Wharf’s two theatres, at the 900-seat Sydney Sydney Theatre Company Limited. Theatre Walsh Bay, at the Drama Theatre of the Sydney Opera Incorporated in New South Wales. A company limited by guarantee. House, throughout NSW, nationally, and increasingly on stages around the world. ABN 87 001 667 983 The Company has been a creative incubator for many of the country’s most distinguished artists and continues to be a platform for discovering new talent. Artists such as Baz Luhrmann, Judy Davis, Toni Collette, Hugo Weaving, Cate Blanchett, Miranda Otto and Geoffrey Rush all honed their skills at STC. Today, the Company collaborates with leading artists and companies from home and abroad, including, most recently, the leading Chekhov exponent Tamás Ascher, directors Steven Soderbergh and Liv Ullman, and physical theatre outfit Frantic Assembly.