C2D Working Paper Series 2006/1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Increased cost to consumers • Increased cost to consumers • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an extremely heavy-handed approach. -

Resourcing Parliament

A.14 RESOURCING PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENTARY APPROPRIATIONS REVIEW REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE SECOND TRIENNIAL REVIEW November 2004 CONTENTS PART ONE: INTRODUCTION.....................................................................1 1.1 Background ..................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope and Purpose of Review ............................................................ 2 1.3 The Parliamentary Environment and MMP............................................ 2 1.4 Principles for Resourcing Parliament ................................................... 3 1.5 Key Directions ................................................................................. 4 1.6 The Fiscal Context............................................................................ 5 1.7 Our Process..................................................................................... 5 PART TWO: DEVELOPMENTS FROM THE 2002 REVIEW ............................7 2.1 Commentary ................................................................................... 7 2.2 Actions Taken on 2002 Report ........................................................... 7 2.3 Our Assessment of Progress on the 2002 Report ................................ 12 PART THREE: RESOURCING PRIORITIES ...............................................13 3.1 Commentary ................................................................................. 13 3.2 Expenditure Trends ........................................................................ 14 -

Resourcing Parliament

A.2 (a) RESOURCING PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENTARY APPROPRIATIONS REVIEW REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE SECOND TRIENNIAL REVIEW November 2004 CONTENTS PART ONE: INTRODUCTION......................................................................1 1.1 Background ..................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope and Purpose of Review ............................................................ 2 1.3 The Parliamentary Environment and MMP............................................ 2 1.4 Principles for Resourcing Parliament ................................................... 3 1.5 Key Directions ................................................................................. 4 1.6 The Fiscal Context............................................................................ 5 1.7 Our Process..................................................................................... 5 PART TWO: DEVELOPMENTS FROM THE 2002 REVIEW .............................7 2.1 Commentary ................................................................................... 7 2.2 Actions Taken on 2002 Report ........................................................... 7 2.3 Our Assessment of Progress on the 2002 Report ................................ 12 PART THREE: RESOURCING PRIORITIES ................................................13 3.1 Commentary ................................................................................. 13 3.2 Expenditure Trends ....................................................................... -

Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD)

First Session, Forty-seventh Parliament, 2002-2003 Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD) Wednesday, 25 June 2003 WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND Published under the authority of the House of Representatives—2003 ISSN 0114-992 X WEDNESDAY, 25 JUNE 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPEAKER’S RULINGS— Independent—Disclosure of Correspondence with Speaker .............................6543 TABLING OF DOCUMENTS— Prostitution Reform Bill.....................................................................................6543 MOTIONS— Dr John Hood.....................................................................................................6543 SPEAKER’S RULINGS— Responses to Oral Questions .............................................................................6544 QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWER— Questions to Ministers— Myanmar—Aung San Suu Kyi.....................................................................6544 Foreshore and Seabed—Crown Ownership..................................................6545 Immigration—Cost to Taxpayers..................................................................6549 Justice, Associate Minister—Confidence .....................................................6551 Hazardous Substances—Regulation .............................................................6553 Genetic Modification—Sheep, PPL Therapeutics, Waikato.........................6553 Foreshore and Seabed—Crown Ownership..................................................6554 Whaling—International Whaling Commission ............................................6556 Defence -

Important Notice

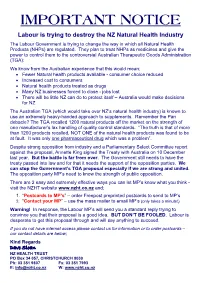

IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour is trying to destroy the NZ Natural Health Industry The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) are regulated. They plan to treat NHPs as medicines and give the power to control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA): We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; • Fewer Natural health products available - consumer choice reduced • Increased cost to consumers • Natural health products treated as drugs • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s natural health industry) is known to use an extremely heavy-handed approach to supplements. Remember the Pan debacle? The TGA recalled 1200 natural products off the market on the strength of one manufacturer’s lax handling of quality control standards. “The truth is that of more than 1200 products recalled, NOT ONE of the natural health products was found to be at fault. It was only one pharmaceutical drug which was a problem”. Despite strong opposition from industry and a Parliamentary Select Committee report against the proposal, Annette King signed the Treaty with Australia on 10 December last year. But the battle is far from over. The Government still needs to have the treaty passed into law and for that it needs the support of the opposition parties. We can stop the Government’s TGA proposal especially if we are strong and united. The opposition party MP’s need to know the strength of public opposition. -

From Human Rights to Law and Order: the Changing Relationship Between Trafficking and Prostitution in Aotearoa/New Zealand Policy Discourse

5 From human rights to law and order: The changing relationship between trafficking and prostitution in Aotearoa/New Zealand policy discourse CARISA R. SHOWDEN Abstract At any given time, multiple and potentially conflicting discourses are circulating in public policy debates. This article uses critical discourse analysis to examine why and how the discourses about the prevalence, causes, and remedies for exploitation in sex work that won the day in the Prostitution Reform Act 2003 debates in Aotearoa/New Zealand have been reinterpreted and reordered in recent debates on trafficking provisions (Section 98D) in the Crimes Amendment Act 2015. Gender equity and human rights were successfully married to a social welfare and harm-minimisation approach in the Prostitution Reform Act debates, whereas they were tied more closely to a law-and-order framework in the latest revisions to Aotearoa/New Zealand’s anti-trafficking policies. This paper argues that the influence of the United States in interpreting and enforcing international anti-trafficking treaties – particularly the ‘Palermo Protocol’ – has facilitated shifts in Aotearoa/New Zealand’s domestic policy and provided leverage to discursive framings that were less successful when prostitution reform was debated at the turn of the twenty-first century. Keywords Prostitution, trafficking, Prostitution Reform Act, Palermo Protocol, discourse analysis Introduction With the passage of the Prostitution Reform Act (PRA) in 2003, Aotearoa/New Zealand became the first country in the world to decriminalise prostitution.1 This law recognised the right to consensual sex work and the need to protect those engaged in it, and in so doing resisted conflating sex work with sex trafficking. -

Believe the Best • Speak to a Person's Potential • Do the Best We Can With

YWAM ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL KEEPING IN TOUCH WITH THOSE WHO HAVE SERVED became the calling for our whole family. We were ‘Born to Serve,’ yet the expression of how we would serve would be different for each of us. It was not really important if we were in business, church, home, by JOHN DEVRIES or any form of employment. What was important was how we lived and what we did with what He had given to us. As we started The first time I experienced God’s love and heard His voice, to emphasize ‘being’ (as in being rooted in the vine - John 15), I wanted to be in ministry. But my dilemma, as I grew in my our ‘doing’ became easier. We were consciously looking to each relationship with the Lord, was that somehow my business activity day with excitement and asking the Father how we could serve. – which at the time was not very successful – did not seem to He was always faithful to show us. cut it. It did not remotely resemble ministry, as I understood that We had opportunities to serve by taking people into our home to be. to live with us. We were able to give encouragement to others. It was during this time that the Lord began to expand my My wife Sandra took a two-year counseling course so she would understanding – He made me aware that my business was my be better qualified to help those whom the Lord had put in her ministry and my ministry was my business. It was not so much path. -

Te Awamutu Courier, Thursday, October 23, 2008 Brass Band Honours Its Own from Page 1

CARING FOR YOUR SAFETY Autorobot Straightening Body Alignment Systems 24 Hour Salvage Ph (07) 871-5069 Bond Road, Te Awamutu, P.O. Box 437 6527647AA Fax (07) 871-4069 A/H (07) 871-7336 email: [email protected] Published Tuesday and Thursday THURSDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2008 Circulated FREE to all households throughout Te Awamutu and surrounding districts. Extra copies 40c. BRIEFLY Appeal for new Six decades of brass home for Harold BY DEAN TAYLOR Waipa King Country Life Education Trust has launched Members of the brass band an appeal after fire extensively fraternity gathered to celebrate a damaged its mobile classroom unique honour when Te Awamutu in a suspected arson last week. Brass member David Haberfield The classroom and its was presented with a certificate programmes cost $100,000 a for sixty years of service. year to operate and maintain What was most unique was that and now extra funding is Mr Haberfield has been with Te needed to get a replacement Awamutu Brass his entire band- classroom back on the road. ing career — and doesn’t plan to The Trust relies on quit just yet. community support and its As well as official recognition sponsors for funding as it from the Brass Band Association doesn’t receive any of New Zealand (BBANZ) and his own band, Waipa Mayor Alan Government assistance. Livingston was on hand to make a Donations can be left at any presentation for such dis- branch of Westpac in the tinguished service on behalf of Te Waipa/King Country area, or Awamutu and district. cheques can be posted to PO Mr Haberfield joined the then Box 317, Te Awamutu.