The Struggle for Control of Procedural Rulemaking Power*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arkansas Supreme Court

ARKANSAS SUPREME COURT State Contracts Over $50,000 Awarded To Minority Owned Businesses Fiscal Year 2020 None Employment Summary Male Female Total % White Employees 13 29 42 89 % Black Employees 2 1 3 6 % Other Racial Minorities 1 1 2 5 % Total Minorities 5 11 % Total Employees 47 100 % Publications A.C.A. 25-1-201 et seq. Required for Unbound Black & Cost of Unbound Statutory # of Reason(s) for Continued White Copies Copies Produced Name General Authorization Governor Copies Publication and Distribution Produced During During the Last Assembly the Last Two Years Two Years Arkansas Reports/ AR Appellate ACA 16-11-201; AR Supreme N N 0 Publication of the Supreme Court opinions 0 0.00 Reports Court Rule 5-2 ceased with volume 375 Ark/104 Ark. App. These opinions are now published online. IN RE: Arkansas Supreme Court and Court of Appeals Rule 5-2 (May 28, 2009) ARKANSAS SUPREME COURT - 0032 Page 1 Honorable John Dan Kemp, Chief Justice ARKANSAS SUPREME COURT - 0032 Honorable John Dan Kemp, Chief Justice Department Appropriation Summary Historical Data Agency Request and Executive Recommendation 2019-2020 2020-2021 2020-2021 2021-2022 2022-2023 Appropriation Actual Pos Budget Pos Authorized Pos Agency Pos Executive Pos Agency Pos Executive Pos 008 Supreme Court - Operations 5,155,467 48 6,013,886 48 5,329,935 48 5,958,765 48 0 0 5,959,010 48 0 0 C66 SC Bar of Arkansas-Cash 3,753,854 25 5,075,000 25 5,075,000 25 5,279,200 25 0 0 5,279,200 25 0 0 Total 8,909,321 73 11,088,886 73 10,404,935 73 11,237,965 73 0 0 11,238,210 73 0 0 Funding Sources % % % % % % State Central Services 4000035 5,155,467 57.9 6,013,886 54.2 5,958,765 53.0 0 0.0 5,959,010 53.0 0 0.0 Cash Fund 4000045 3,753,854 42.1 5,075,000 45.8 5,279,200 47.0 0 0.0 5,279,200 47.0 0 0.0 Total Funds 8,909,321 100.0 11,088,886 100.0 11,237,965 100.0 0 0.0 11,238,210 100.0 0 0.0 Excess Appropriation/(Funding) 0 0 0 0 0 0 Grand Total 8,909,321 11,088,886 11,237,965 0 11,238,210 0 FY21 Budget amount in 008 exceeds the authorized amount due to salary and matching rate adjustments during the 2019-2021 Biennium. -

Appellate Update January 2020

APPELLATE LJPDATE PUBLISHED BY THE JANUARY 2O2O ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS VOLUME 27, NO. 5 Appellate Update is a service provided by the Administrative Office of the Courts to assist in locating published decisions of the Arkansas Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals. It is.not an official publication of the Supreme Court or the Court of Appeals. It is not intended to be a complete summary of each case; rather, it highlights some of the issues in the case. A case of interest can be found in its entirety by searching this website: https ://opinions. arcourts. gov/ark/enlnav' do ANNOUNCEMENTS On December 19,2019, amendments to the Rule and Regulations governing Court Reporters were published for comment. The comment period expires on March 31,2020. CRIMINAL Harper v. State,2020 Ark. App, 4 [Ark. Code Ann. $ 16-39-1151 Appellant sought disclosure and review of notes taken by the prosecutor during an interview with the victim. After conducting an in camera review, the circuit court concluded that: (1) the prosecutor's notes were not a statement as defined by Arkansas Code Annotated $ 16-89-115; (2) the notes contained no information that probably would have changed the outcome of the trial; and (3) the nondisclosure of the notes is harmless beyond a reasonable doubt because the information in the notes was readily available through other discovery provided in the case by the State. Arkansas Code on direct Annotated $ 16-89-115(b) provides that after awitness called by the State has testified examination, the court on motion of the defendant shall order the State to produce any statement of the witness in the possession of the State that relates to the subject matter about which the -1- witness has testified. -

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures The Vermont Public Interest Action Project Office of Career Services Vermont Law School Copyright © 2021 Vermont Law School Acknowledgement The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures represents the contributions of several individuals and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their ideas and energy. We would like to acknowledge and thank the state court administrators, clerks, and other personnel for continuing to provide the information necessary to compile this volume. Likewise, the assistance of career services offices in several jurisdictions is also very much appreciated. Lastly, thank you to Elijah Gleason in our office for gathering and updating the information in this year’s Guide. Quite simply, the 2021-2022 Guide exists because of their efforts, and we are very appreciative of their work on this project. We have made every effort to verify the information that is contained herein, but judges and courts can, and do, alter application deadlines and materials. As a result, if you have any questions about the information listed, please confirm it directly with the individual court involved. It is likely that additional changes will occur in the coming months, which we will monitor and update in the Guide accordingly. We believe The 2021-2022 Guide represents a necessary tool for both career services professionals and law students considering judicial clerkships. We hope that it will prove useful and encourage other efforts to share information of use to all of us in the law school career services community. -

16-992 Pavan V. Smith (06/26/2017)

Cite as: 582 U. S. ____ (2017) 1 Per Curiam SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES MARISA N. PAVAN, ET AL. v. NATHANIEL SMITH ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS No. 16–992. Decided June 26, 2017 PER CURIAM. As this Court explained in Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U. S. ___ (2015), the Constitution entitles same-sex cou- ples to civil marriage “on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples.” Id., at ___ (slip op., at 23). In the decision below, the Arkansas Supreme Court considered the effect of that holding on the State’s rules governing the issuance of birth certificates. When a married woman gives birth in Arkansas, state law generally requires the name of the mother’s male spouse to appear on the child’s birth certificate—regardless of his biological relationship to the child. According to the court below, however, Ar- kansas need not extend that rule to similarly situated same-sex couples: The State need not, in other words, issue birth certificates including the female spouses of women who give birth in the State. Because that differen- tial treatment infringes Obergefell’s commitment to pro- vide same-sex couples “the constellation of benefits that the States have linked to marriage,” id., at ___ (slip op., at 17), we reverse the state court’s judgment. The petitioners here are two married same-sex couples who conceived children through anonymous sperm dona- tion. Leigh and Jana Jacobs were married in Iowa in 2010, and Terrah and Marisa Pavan were married in New Hampshire in 2011. -

House Style Guide

House Style Guide Arkansas Supreme Court Arkansas Court of Appeals Susan P. Williams Reporter of Decisions Tina Huddleson Deputy Reporter of Decisions September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... ii OPINION FORMAT AND STYLE ........................................................................................... 1 1.1 General Opinion Formatting Conventions ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Case Caption, Docket Number, Opinion Date .................................................................. 3 1.3 Authoring Justices and Judges ............................................................................................... 4 1.4 Introduction of Abbreviated Names and Acronyms ......................................................... 5 1.5 “Em” Dashes, “En” Dashes, and Hyphens ........................................................................ 5 1.6 Quotations ............................................................................................................................... 6 CITATION OF ARKANSAS-SPECIFIC SOURCES .......................................................... 10 2.1 Cases ....................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Special Citation Forms for Other Court Opinions .......................................................... 12 2.3 Arkansas Constitution -

And the State Courts

national Summit on Human trafficking and the State Courts oCtoBer 7 – 9, 2015 new York CitY — downtow n marriott Hon. JonatHan Lippman Chief Judge of the State of new York Chief Judge of the new York State Court of appeals the Summit is sponsored by and planned in partnership with the State Justice institute, the Conference of Chief Justices, the Conference of State Court administrators, the national Center for State Courts, the Human trafficking and the State Courts Collaborative, the new York State Bar association, the women’s Bar association of the State of new York and the new York State office of Court administration. national Summit on Human trafficking and the State Courts WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 7 4:00 – 7:00 P.M. EARLY REGISTRATION EW YORK IS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8 “ 7:30 – 8:45 A.M. REGISTRATION & BREAKFAST nTHRILLED TO HOST this incredible 8:45 – 8:55 A.M. WELCOME & INTRODUCTION opportunity to raise Hon. Lawrence K. Marks (NY) Chief Administrative Judge of the Courts of the State of New York awareness about the 8:55 – 9:05 A.M. nature, scale and scope REMARKS – “The Role of SJI” Hon. Jim R. Hannah (AR) of human trafficking State Justice Institute (SJI) Board Chairman, former President of the Conference of Chief Justices and Chair of the Board of the National Center for State Courts, and former Chief Justice of the and the important role Arkansas Supreme Court the state courts can 9:05 – 9:20 A.M. KEYNOTE REMARKS play in combating this Hon. Jonathan Lippman Chief Judge of the State of New York scourge of modern 9:20 – 10:20 A.M. -

ARKANSAS William Stuart Jackson Jane A. Kim

ARKANSAS William Stuart Jackson Jane A. Kim Wright, Lindsey & Jennings LLP 200 West Capitol Avenue, Suite 2300 Little Rock, Arkansas 72201-3699 Tel: (501) 371-0808 Fax: (501) 376-9442 Web: www.wlj.com E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] I. AT-WILL EMPLOYMENT A. Statute Arkansas has no statute that determines the status of an employee. B. Case Law An employer or an employee may terminate an employment relationship at- will, except where there is an agreement that the employment is for a specified time, in which case termination may only be for cause. Additionally, a termination may only be for cause where an employer's employment manual contains an express and definite provision stating that the employee will only be dismissed for cause and that provision is relied on by the employee. Crain Indus., Inc. v. Cass, 810 S.W.2d 910, 305 Ark. 566 (1991). II. EXCEPTIONS TO AT-WILL EMPLOYMENT A. Implied Contracts 1. Employee Handbooks/Personnel Materials Where an employment manual contains provisions stating that employment is at-will and that the employer may terminate the employment “at any time for any reason,” other provisions of the manual setting forth disciplinary procedures and written explanations for termination do not modify at-will employment and the plaintiff had no property interest giving rise to due process protections. Thompson v. Adams, 268 F.3d 609 (8th Cir. 2001). A policy and procedures manual distributed to employees in which the employer states that discipline shall be for cause, but also explicitly states that termination may be without cause, does not modify an employment at-will relationship under the employee handbook/policy manual exception to the at-will doctrine. -

Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, and Circuit Courts for the Period January 1, 2013 Through June 30, 2015

Special Report Arkansas Legislative Audit Information Regarding the Arkansas Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, and Circuit Courts For the Period January 1, 2013 through June 30, 2015 INTRODUCTION This report is issued to provide information regarding the Arkansas Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, and Circuit Courts (i.e., trial and appellate courts, excluding District Courts). The information provided includes the history of the courts, caseloads, and financial data. Overall, for the period reviewed, annualized revenues for the State's trial and appellate courts totaled $166.2 million, while annualized expenditures totaled $201.8 million. The deficit is primarily absorbed at the county level through the counties' general funds. OBJECTIVES The objectives of this review were to: Provide the structure and history of the Arkansas court system's trial and appellate courts. Categorize caseloads by judicial district. Describe how funds flow between state government and local governments. Compile a listing of revenues by source, by judicial district. Provide salary expenditures by judicial district. Provide additional county- and state-funded expenditures by judicial district. SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY The information provided in the report was obtained from the Arkansas Administrative Statewide Information System (AASIS), Arkansas Code, relevant reports from various state agencies, and information from local government entities that was requested by Arkansas Legislative Audit (ALA) staff. Due to differences in reporting periods, the information for state government is for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2015; the information for local governments is for the calendar year ended December 31, 2014; and the information for prosecuting attorneys is for the calendar year ended December 31, 2013. -

The Debate Over the Selection and Retention of Judges: How Judges Can Ride the Wave

AN AMERICAN JUDGES ASSOCIATION WHITE PAPER The Debate over the Selection and Retention of Judges: How Judges Can Ride the Wave Mary A. Celeste here is a surge in the debate in the U.S. over the methods involve four different selection methods: lifetime appoint- of judicial selection and retention, with some rallying for ment, partisan election, nonpartisan election, and merit selec- Tmerit-selection plans, others continuing to support judi- tion and retention. These movements have been in a constant cial elections, and virtually no one proposing lifetime appoint- state of flux, with many states using constitutional amend- ments. The impetus for this surge may be related to three ments, legislative acts, ballot initiatives, and executive orders recent U.S. Supreme Court cases, Republican Party of Minnesota to both move in and out of the methods, and to make modifi- v. White,1 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,2 and cations short of complete overhauls. For example, 9 of 16 Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co.,3 and to the exploding amount states that initially only used the appointment method of campaign funds raised in judicial elections. These factors switched to judicial elections for some level of their judiciary,5 seem to have once again brought to the forefront the judicial 14 states changed from partisan to nonpartisan elections,6 and election method and consequently revitalized the merit 15 states have changed from partisan or nonpartisan elections method, which had been dormant for three decades. Whether to some form of the merit method.7 When all is said and done, this boost in the debate is tantamount to a new movement, a over the last 234 years, this activity has resulted in 39 states continuation of an old movement, a blip on the radar screen, a deviating substantially from their initial selection method. -

Order List: 589 Us

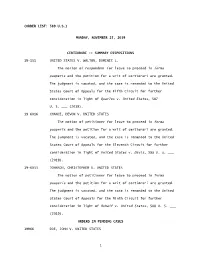

(ORDER LIST: 589 U.S.) MONDAY, NOVEMBER 25, 2019 CERTIORARI -- SUMMARY DISPOSITIONS 19-151 UNITED STATES V. WALTON, DOMINIC L. The motion of respondent for leave to proceed in forma pauperis and the petition for a writ of certiorari are granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit for further consideration in light of Quarles v. United States, 587 U. S. ___ (2019). 19-6016 CHANCE, DEVON V. UNITED STATES The motion of petitioner for leave to proceed in forma pauperis and the petition for a writ of certiorari are granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit for further consideration in light of United States v. Davis, 588 U. S. ___ (2019). 19-6033 JOHNSON, CHRISTOPHER V. UNITED STATES The motion of petitioner for leave to proceed in forma pauperis and the petition for a writ of certiorari are granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit for further consideration in light of Rehaif v. United States, 588 U. S. ___ (2019). ORDERS IN PENDING CASES 19M66 DOE, JOHN V. UNITED STATES 1 The motion for leave to file a petition for a writ of certiorari with the supplemental appendix under seal is granted. 19M67 LEVY GARDENS PARTNERS 2007, L.P. V. LEWIS TITLE CO., INC., ET AL. 19M68 JOHNSON, JODY M. V. INCH, SEC., FL DOC, ET AL. 19M69 LIU, XIAO QING V. -

IN the Supreme Court of the United States ———— HON

No. -____ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— HON. WENDELL GRIFFEN, Petitioner, v. HON. JOHN DAN KEMP, ET AL., Respondents. ———— On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ———— PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ———— MICHAEL J. LAUX MICHAEL P. MATTHEWS LAUX LAW GROUP Counsel of Record 400 W. Capitol Ave., LAWRENCE J. DOUGHERTY # 1700 RACHEL E. KRAMER Little Rock, AR 72201 ANDREW M. MEERKINS (501) 242-0750 FOLEY & LARDNER LLP 100 N. Tampa St., # 2700 AUSTIN PORTER, JR. Tampa, FL 33602 PORTER LAW FIRM (813) 229-2300 323 Center St., # 1035 [email protected] Little Rock, AR 72201 (501) 244-8200 Counsel for the Hon. Wendell Griffen Petitioner for a Writ of Certiorari WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D.C. 20002 QUESTIONS PRESENTED In this civil rights action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, a divided panel of the Eighth Circuit purported to exercise jurisdiction under the All Writs Act to conduct appellate review of a non-final order of the district court denying dismissal of the complaint and to issue a writ of mandamus ordering dismissal. In re Kemp, 894 F.3d 900 (8th Cir. 2018); App., infra, 2a-15a. The questions presented for review are: 1. Whether the All Writs Acts grants the circuit courts jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus to review on the merits a district court’s non-final denial of a motion to dismiss. 2. Whether the Eighth Circuit’s review of the facial sufficiency of the § 1983 complaint below ignored the requirements of Johnson v. -

State of the Judiciary Chief Justice John Dan Kemp June 12, 2020

State of the Judiciary Chief Justice John Dan Kemp June 12, 2020 President Rosenthal, President-Elect Keith, Fellow Justices and Judges, Members of the Bar, and Guests: Introduction It’s always a pleasure to have the opportunity to address the joint meeting of the Arkansas Bar Association and the Arkansas Judicial Council, even more so when it’s a history- making first-ever virtual Arkansas Bar Association conference. A few short months ago, no one could have predicted the impact COVID-19 would have on our communities. My heart goes out to the thousands of Arkansans who have overcome this disease. I would also like to offer my condolences to the families in our state who have lost loved ones during this pandemic. It is often said that the Judiciary is the slowest of the three branches of government to act. In this case, I would dispute that assumption. I would like to share with you the progress that is being made within the judicial branch of our government, which quickly adapted in remarkable ways during this challenging time. I appreciate Arkansas Bar Association President Brian Rosenthal offering me this platform, and I commend him on an excellent year of service to the Bar Association. The state of the Arkansas Judiciary is in very good condition thanks to the extraordinary work of its circuit and district judges, its appellate justices and judges, the members of their staff, and clerk’s office and Administrative Office of the Courts. COVID-19 Response On March 6, 2020, the Arkansas Supreme Court issued a statement on the COVID-19 outbreak in which we encouraged the Court Community to begin working with their local county officials to review emergency Continuity of Operations plans to prepare for the pandemic.