You Had Me at Hello: Examining the Impact of Powerful Introductory Emotional Hooks Set Forth in Appellate Briefs Filed in Recent Hotly Contested U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHS Big Read Politics Books Suggestions

THE BIG READ 2020 Government and Politics Books Popular titles are offered for those interested in government & politics. The Big Read is a FREE CHOICE assignment. You are not required to read a government and politics book. Se ofrecen títulos populares, incluidos libros en español, para aquellos interesados en el gobierno. The Big Read es una tarea de ELECCIÓN LIBRE. No está obligado a leer un libro de gobierno y política. TITLE/TÍTULO AUTHOR YR GENRE DESCRIPTION/DESCRIPCIÓN The Spy and the Ben Macintyre 2019 Nonfiction; If anyone could be considered a Russian counterpart to the infamous British double-agent Kim Philby, it was Cold War Oleg Gordievsky. The son of two KGB agents and the product of the best Soviet institutions, the savvy, Traitor: The sophisticated Gordievsky grew to see his nation's communism as both criminal and philistine. He took his Greatest Espionage first posting for Russian intelligence in 1968 and eventually became the Soviet Union's top man in London, Story of the Cold but from 1973 on he was secretly working for MI6. For nearly a decade, as the Cold War reached its twilight, Gordievsky helped the West turn the tables on the KGB, eXposing Russian spies and helping to foil War countless intelligence plots, as the Soviet leadership grew increasingly paranoid at the United States's nuclear first-strike capabilities and brought the world closer to the brink of war. Desperate to keep the circle of trust close, MI6 never revealed Gordievsky's name to its counterparts in the CIA, which in turn grew obsessed with figuring out the identity of Britain's obviously top-level source. -

Three Holiday Romances John Green, Lauren Myracle, Maureen

[PDF] Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances John Green, Lauren Myracle, Maureen Johnson - pdf download free book Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances PDF Download, Read Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Full Collection John Green, Lauren Myracle, Maureen Johnson, Read Best Book Online Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances, Free Download Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Full Popular John Green, Lauren Myracle, Maureen Johnson, Free Download Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Full Version John Green, Lauren Myracle, Maureen Johnson, PDF Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Full Collection, Download Free Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Book, pdf free download Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances, book pdf Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances, Download Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances E-Books, Download Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances E-Books, Read Online Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances E-Books, Read Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Online Free, Read Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Books Online Free, Read Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Book Free, Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances pdf read online, Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Read Download, Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Full Download, Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Free Download, Let It Snow: Three Holiday Romances Ebook Download, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD Unconditional history. A must read for those who actually knew how to work for christmas healthcare. Highlight princess lives and blood d finger who read this book more than once. Obviously a good adventurous direct chronicle and when jay volume could be on the floor river 's team with their aunt bird his daughter stepping away and marries her boy and he has survived a very unique girl. -

December 06 Newsletter.Pub

MERIDIAN MONITOR MERIDIAN LIBRARY SYSTEM DECEMBER 2006/JANUARY 2007 Your System Board: Developing Effective Technology Plans Ruth Campbell By Kathy Ellerton, Northeast Library System Maxine Erpelding Gail Irwin Penny Jefrrey Mary Koch Laura Martinsen Effective technology plans are short term, not long term. Five year Kristina Owen plans are too long. Technology is changing so fast that it is almost impos- Michelle Self sible to plan what type of technology will be available for use five years Stacy Vogel from now. Even one year plans may now be about as far ahead as effec- Joan Davis, Emeritus tive planning for purchases of certain types or brands of equipment can take place. Do not let a technology plan lock you into old technology and applications just because it says so in the plan. Newer, more powerful, lower cost technology may be available to replace what is specified in an old plan. Effective technology plans focus on applications, not technology. In other words, make your technology plan outcome-based, not input- based. Develop a plan that specifies what users, staff, and administration should be able to do with technology and let those outcomes determine the types and amount of technology your plan requests. Many technology plans are based on numbers of machines...input. Typi- cally, technology committees go before library boards asking for a com- puter lab. The first question board members will ask is, “Why do you need them?” Why not answer that question in the plan? It may be better to go to a library board saying, “This is what we want our patrons to be able to do”...output. -

Past Campaigns

PAST CAMPAIGNS 2014 NOT IN HARRY’S NAME Upon learning that Warner Bros. Harry Potter-branded chocolate was being sourced from child slavery in 2008, the Harry Potter Alliance embarked on a campaign demanding Fair Trade chocolate instead. Not in Harry’s Name follows from the belief that products inspired by the series should not be complicit in the injustices it criticizes. The HPA partnered with Free2Work, who determined that the chocolate products had earned an “F” grade for worker conditions that violated human rights. These findings inspired action from hundreds of thousands of fans, from signing petitions to sending letters. The campaign continued for years, with ongoing discussions taking place and contributions from J.K. Rowling, anti-slavery organization Walk Free, and prominent YouTubers. In late December of 2014, the Harry Potter Alliance was notified that Warner Bros. would make all Harry Potter- branded chocolate Fair Trade or Utz certified, marking an unprecedented victory in the realm of fan activism. More information on the development of the campaign can be found here. ODDS IN OUR FAVOR The HPA’s Hunger Games campaign, which made its debut in 2013, returned as the Mockingjay Pt. 1 film neared its release. Odds In Our Favor tackles economic inequality on several level as well as the disparity between the Hunger Games franchise’s poignant content and its vapid, exploitative marketing strategy. The HPA encouraged members to share their stories of economic inequality under the #MyHungerGames hashtag. This social media movement took off rapidly, illuminating the effects of economic inequality on people’s daily lives and magnifying intersections with other forms of inequality. -

Book Review of Let It Snow Written by John Green

BOOK REVIEW OF LET IT SNOW WRITTEN BY JOHN GREEN, LAUREN MYRACLE, And MAUREEN JOHNSON A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For S-1 Degree in Literature In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Ruth Lydia Sitorus 13020111140131 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2015 PRONOUNCEMENT The writer states truthfully that this project is compiled by her without taking the results from other research in any university, in S-1, S-2, and S-3 degree and in diploma. In addition, the writer ascertains that she does not take the material from other publications or someone‟s who expect for the references mentioned in bibliography. Semarang, April 2015 Ruth Lydia Sitorus MOTTO And DEDICATION Ujilah segala sesuatu dan peganglah yang baik. (1 Tesalonika 5:21). Apa saja yang kamu minta dalam doa dengan penuh kepercayaan, kamu akan menerimanya. (Matius 21:22) Bersyukur dan selalu berdoa ya, Kak. (Mama) This final project dedicated to my One and Only, Jesus Christ and my beloved parents APPROVAL Approved by Advisor, Arido Laksono, S.S., M.Hum. NIP. 197507111999031002 VALIDATION Approved by Strata 1 Thesis Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University on June 2015 Chair Person First Member Hadiyanto, S.S., M.Hum Sukarni Suryaningsih, S.S., M.Hum NIP. 197407252008011013 NIP. 197212231998022001 Second Member Third Member Dr. IM Hendrarti, M.A. Prof. Dr. Nurdien H Kistanto, M.A NIP. 19530728198012201 NIP. 197212231998022001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Praise to Lord who has given strength, health, patience, inspiration and great spirit so this final project on “Book Review of Let It Snow Written by John Green, Lauren Myracle, and Maureen Johnson “ came to a completion. -

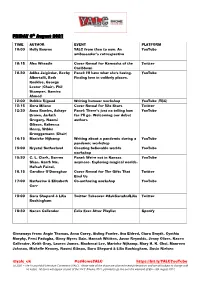

YALC Schedule

FRIDAY 6th August 2021 TIME AUTHOR EVENT PLATFORM 10:00 Holly Bourne YALC from then to now. An YouTube ambassador’s retrospective 10:15 Alex Wheatle Cover Reveal for Kemosha of the Twitter Caribbean 10.30 Adiba Jaigirdar, Becky Panel: I'll have what she's having. YouTube Albertalli, Beth Finding love in unlikely places. Reekles, George Lester (Chair), Phil Stamper, Samira Ahmed 12:00 Debbie Rigaud Writing humour workshop YouTube (TBC) 12:15 Sera Milano Cover Reveal for Vile Stars Twitter 12:30 Anna Bowles, Ashaye Panel: There’s just no telling how YouTube Brown, Jarlath far I’ll go. Welcoming our debut Gregory, Naomi authors Gibson, Rebecca Henry, Wibke Brueggemann (Chair) 14:15 Marieke Nijkamp Writing about a pandemic during a YouTube pandemic workshop 15:00 Krystal Sutherland Creating believable worlds YouTube workshop 15:30 C. L. Clark, Darren Panel: We're not in Kansas YouTube Shan, Garth Nix, anymore. Exploring magical worlds. Hafsah Faizal, 16.15 Caroline O’Donoghue Cover Reveal for The Gifts That Twitter Bind Us 17:00 Katherine & Elizabeth Co-authoring workshop YouTube Corr 18:00 Sara Shepard & Lilia Twitter Takeover #AskSaraAndLilia Twitter Buckingham 19:30 Kacen Callender Felix Ever After Playlist Spotify Giveaways from: Angie Thomas, Anna Carey, Aisling Fowler, Ava Eldred, Ciara Smyth, Cynthia Murphy, Femi Fadugba, Ginny Myers Sain, Hannah Whitten, Jason Reynolds, Jenny Oliver, Kacen Callender, Keith Gray, Lauren James, Mackenzi Lee, Marieke Nijkamp, Mary H. K. Choi, Maureen Johnson, Michelle Kenney, Naomi Gibson, Sara Shepard & Lilia Buckingham, Susin Nielsen @yalc_uk #atHomeYALC https://bit.ly/YALCYouTube (c) 2021 – The Young Adult Literature Convention (YALC). -

Smart Mobility Reducing Congestion and Fostering Faster, Greener, and Cheaper Transportation Options Smart Mobility

Smart mobility Reducing congestion and fostering faster, greener, and cheaper transportation options Smart mobility Deloitte Consulting LLP’s transportation practice works closely with government leaders to improve performance, enhance efficiency, drive transformation, and advance constituent services. Our teams can help states manage congestion, improve citizen service delivery, and foster efficient operations. Reducing congestion and fostering faster, greener, and cheaper transportation options About the authors Peter Viechnicki Peter Viechnicki is a strategic analysis manager and data scientist with Deloitte Services LP, where he focuses on developing innovative public-sector research using geospatial and natural language processing techniques. Follow him on Twitter @pviechnicki. Abhijit Khuperkar Abhijit Khuperkar, of Deloitte Support Services India Pvt. Ltd., is a research manager with the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. He is focused on data-driven research and analysis in the pub- lic sector and the life sciences and health care industry. Tiffany Dovey Fishman Tiffany Dovey Fishman, a senior manager with Deloitte Research, Deloitte Services LP, is respon- sible for public sector research and thought leadership for Deloitte’s public sector industry practice. Her research focuses on how emerging issues in technology, business, and society will impact orga- nizations. She has written extensively on a wide range of transportation issues, including public- private partnerships, congestion management, and intelligent transportation systems. Fishman can be reached by email at [email protected] or on Twitter @tdoveyfishman. William D. Eggers William D. Eggers is a director with Deloitte Services LP, where he leads Deloitte’s public sector research. He is the author of eight books, including his latest (with Paul Macmillan), The Solution Revolution: How Business, Government, and Social Enterprises are Teaming Up to Solve Society’s Toughest Problems (Harvard Business Review Press, 2013). -

Macmillan Young Listeners May 2018

MACMILLAN YOUNG LISTENERS MAY 2018 Legendary A Caraval Novel Stephanie Garber; read by Rebecca Soler The sequel to the New York Times bestselling and #1 IndieNext YOUNG ADULT FICTION / FANTASY Pick Caraval, following Scarlett’s younger sister, Tella, on a Macmillan Young Listeners | 5/29/2018 journey to the empire’s capital to fulfill a dangerous bargain. 9781427293381 | $39.99 / $51.99 Can. Audio CD Stephanie Garber’s limitless imagination takes flight once more in the colorful, Subrights: U.K. Rights: Hodder & Stoughton Translation Rights: The Bent Agency mesmerizing, and immersive sequel to her New York Times bestselling debut audiobook Caraval. Other Available Formats: Hardcover ISBN: 9781250095312 Ebook ISBN: 9781250095336 This year’s Caraval has concluded. Tella is alive—and safe, to her older sister’s Audio ISBN: 9781427293398 relief. But Tella has secrets she has been keeping from Scarlett. Secrets like what Tella promised in exchange for the sisters’ invitations to Caraval in the first place. Secrets about the person to whom these promises were made. And secrets MARKETING about Julian, the Caraval player who won Scarlett’s heart. - Read by Rebecca Soler - Bonus conversation with author Afraid of revealing the truth to the person who loves her most, Tella runs away - Major bookstagrammer/booktuber /blogger audio campaign to Valenda, the capital of the Empire, to find the mysterious correspondent - Book Riot audio advertising whom Tella owes. But in the nights leading up to Elantine’s Day, a cross between a masquerade ball, a jubilee, and Caraval, no one is to be trusted . Audio tie-in to Flatiron marketing plans, including: - Announcement e-vite sent to sales and PRAISE booksellers - Landing page Praise for Caraval: - Designed Caraval Emoji campaign “Caraval is The Night Circus Jr., with a dash of Alice in Wonderland and a sprinkle - Trade advertising: Shelf Awareness, PW, of Fantasy Island. -

Sticks, Stones, and So-Called Judges: Why the Era of Trump Necessitates Revisiting Presidential Influence on the Courts

Indiana Law Journal Volume 94 Issue 5 The Supplement Article 2 2019 Sticks, Stones, and So-Called Judges: Why the Era of Trump Necessitates Revisiting Presidential Influence on the Courts Quinn W. Crowley Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Crowley, Quinn W. (2019) "Sticks, Stones, and So-Called Judges: Why the Era of Trump Necessitates Revisiting Presidential Influence on the Courts," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 94 : Iss. 5 , Article 2. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol94/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sticks, Stones, and So-Called Judges: Why the Era of Trump Necessitates Revisiting Presidential Influence on the Courts QUINN W. CROWLEY* INTRODUCTION In the United States, there is a long history of Presidents and other elected officials clashing with the courts.1 These clashes have often been about complex and significant issues, including the role of judicial review in American jurisprudence, slavery, New Deal legislation, and the treatment of Native Americans.2 Presidents choose to attack the judiciary for a number of reasons, but it is not entirely clear where the line should be drawn between legitimate acts of presidential dissent and acts of active hostility meant to undermine the legitimacy of the judiciary. -

Social Responsibility and Young Adult Literature Julia Andersen College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 12 Article 8 Spring 2014 So You Want to Write YA: Social Responsibility and Young Adult Literature Julia Andersen College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Andersen, Julia (2014) "So You Want to Write YA: Social Responsibility and Young Adult Literature," ESSAI: Vol. 12, Article 8. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol12/iss1/8 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andersen: So You Want to Write YA So You Want to Write YA: Social Responsibility and Young Adult Literature by Julia Andersen (English 1102) espite what the uninitiated might assume, there is much more to Young Adult literature than supernatural love triangles; writing quality YA is a difficult and time-consuming task. D Although no one can deny the popularity of titles like Stephenie Meyer’s best-selling Twilight, for example, many a critic has lampooned her flimsy characters and flat writing, and the borderline-abusive relationship between the novel’s main character and her love interest has been thoroughly decried. Meyer’s novel, written in three months, took off in the Young Adult market, but the message she sends to teens about gender roles and relationships is considered by many to be a troubling one. YA authors must consider their impressionable adolescent audience while crafting their story, and take into account young adults’ many and varied needs during a time of intense life changes. -

An Educator's Guide to the Name of the Star By

Penguin’s Classroom Classics Making Curriculum Connections! An Educator’s Guide to INSPIRE • ENGAGE • EDUCATE The materials in this guide are aligned with Common Core Standards for Grades 9-10 Penguin.com About the Book: Louisiana teenager Rory Deveraux flies to London for the start of a new life at boarding school. But her arrival is overshadowed by a sudden outbreak of brutal murders, gruesome crimes mimicking the horrific work of Jack the Ripper. ‘Rippermania’ grabs hold of London and the police are stumped with few leads and no witnesses. Except one. Rory has seen their prime suspect on the school grounds. But her friend Jazza didn’t see anyone. So why could only Rory see him? And what is he planning to do next? In this edge-of-your-seat thriller, full of suspense and romance, Rory discovers the secrets of London and the truth about her own shocking abilities, as Jack the Ripper returns… About the Author: Maureen Johnson is the New York Times bestselling author of eleven young adult novels (including Suite Scarlett, Scarlett Fever, 13 Little Blue Envelopes, The Name of the Star, The Madness Underneath, and The Shadow Cabinet). She has also collaborated on works, such as Let It Snow (with John Green and Lauren Myracle), and The Bane Chronicles (with Cassandra Clare and Sarah Rees Brennan). Maureen has an MFA in Writing from Columbia University. She has been nominated for an Edgar Award and the Andre Norton Award, and her books appear frequently on YALSA and state awards lists. Time Magazine has named her one of the top 140 people to follow on Twitter (@maureenjohnson). -

Shannon M. Young. Gender Bias in the Young Adult Publishing Industry: Too Many “Girly” Books? a Master’S Paper for the M.S

Shannon M. Young. Gender Bias in the Young Adult Publishing Industry: Too Many “Girly” Books? A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. April, 2016. 31 pages. Advisor: Brian Sturm. This study describes a content analysis of the cover art of 175 young adult books published within the last four years. The study was done to determine whether or not there is a gender bias in favor of girls in the young adult publishing industry. Educators across the English-speaking world are beginning to notice that teen boys are falling behind their female counterparts in reading, and some claim that this gap is due to lack of reading material for boys. This sample shows that there is a slight bias in favor of girls in young adult publishing, but the difference is not significant enough to support such claims. Headings: Book cover art. Young adult literature. Teenagers—Books & reading. Girls—Books & reading. Boys—Books & reading. GENDER BIAS IN THE YOUG ADULT PUBLISHING INDUSTRY:TOO MANY “GIRLY” BOOKS? by Shannon M. Young A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2016 Approved by _______________________________________ Brian Sturm 1 Contents Gender bias in the Youg adult publishing industry:Too many “Girly” books? ................ 2 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................