ISLAMIC INFLUENCES on JAINA ARCHITECTURE M O B S A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

For One Year. C

Volume : 66 Issue No. : 66 Month : January, 2006 AHIMSA FOUNDATION WISHES A VERY HAPPY & PROSPEROUS NEW YEAR 2006 TO ALL THE ALL PATRONS & READERS TEMPLES PRESIDENT KALAM DECLARES OPEN FIRST MAHAMASTHAKABHISHEKA CEREMONY The hills of Vindhyagiri and Chandragiri in the town of Shravanabelagola resounded with chants of"Bhagawan Bahubali ki jai" as President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam on Sunday, 22nd January 2006 declared open the first Mahamastakabhisheka of the millennium and reiterated the relevance of the Jain tenets of non-violence in a strife-ridden world. Mr. Kalam said the practice of truth, ahimsa and vairagya that are the tenets of Jainism was relevant in modern times and the message of peace and non-violence as enunciated by Bahubali should be taken to all parts of the country. Addressing a vast gathering of Jain munis, nuns, acharyas and devotees who have assembled here from all parts of the world, the President said the spiritual congregation symbolised the continuity of a great tradition, which started in the 3rd century B.C. by Chandragupta Maurya, who settled here with 12,000 sages and munis performing austerities. It is a beautiful sight of people of multiple faiths and affiliations gathering to celebrate a great cultural event. The most sacred meaning of life consists of helping the establishment of peace and harmony on earth. This can only be achieved through the practice of truth, ahimsa and vairagya by all of us," the President said. The Mahamastakabhisheka is held once in 12 years and Sunday's inauguration marked the launching of the events and rituals that will lead up to the grand event of the anointment of the 57-foot statue that will be held Jainsamaj Matrimonial from February 8 to 19. -

Shree Jagannath Temple at Puri : a Study on Aruna Stambha, Simha Dwara and Baisi Pahacha

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Shree Jagannath Temple at Puri : A Study on Aruna Stambha, Simha Dwara and Baisi Pahacha Dr. Benudhar Patra he massive temple of Shree Jagannath (214 Tfeet 8 inches high above the road level) located at Puri (the hallowed srikshetra or the Purushottam kshetra) near the sea (the Bay of Bengal), in the state of Odisha on the eastern coast of India is not only a sacred Hindu temple but also one of the char dhamas (four dhamas/ four traditional pilgrimage centres) of the Hindu devotees and pilgrims. It is the symbol and embodiment of the Odia culture and civilization. The temple was built in the 12th century CE by King Anantavarman Chodaganga Deva (c. 1078 to c. 1147 CE) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty and is moulding the social, economic, political, religious gate (lion gate or simha dwara) of Shree and cultural life of the people of Odisha for Jagannath Temple. The pillar is named so after centuries. The temple is built in the Kalinga style the name of Aruna, the charioteer of the Sun God. of architecture and is significant for its marvellous It is a magnificent sixteen-sided monolithic column art, architecture and sculpture. Apart from the of chlorite stone set on an exquisite pedestal, main temple complex, the aruna stambha delicately carved of the same material. According standing in front of the temple, the simha to R.L.Mitra1 the carvings on the plinth “are of dwara or the lion gate or the main entrance of the most sumptuous description, the like of which the temple and the baisi pahacha (the flight of are to be seen nowhere else in India.” It is 25 twenty two steps) leading into the temple complex feet, and 2 inches in height, 2 feet in diameter, from the simha dwara are very noteworthy to and 6 feet and 3.5 inches in circumference. -

Evaluation of Infrastructure Facilities and Perception of Pilgrims at Palitana

International Journal of Applied Research 2021; 7(3): 284-289 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 8.4 Evaluation of infrastructure facilities and perception IJAR 2021; 7(3): 284-289 of pilgrims at Palitana www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 12-01-2021 Accepted: 14-02-2021 Tanmay Choksi and Anand Kapadia Tanmay Choksi M. Plan Student, Department Abstract of Architecture, Master of Background and Objective: Religious tourism seems to be one of the most preferred tourism after Urban and Regional Planning, business tourism in Gujarat. Palitana is one of the very important pilgrimage destination among six G.C Patel Institute of religious sites in Gujarat. The main objective of this study was to assess the existing infrastructure and Architecture, interior designing institutional framework for tourism in Palitana town and identify the gaps as well as to study perception and Fine Arts, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, of pilgrims at Palitana. Surat, Gujarat, India Methodology: Data collection was done in two phases. Primary data collection was done by using 16 item questionnaire was used to evaluate tourist perception. 100 tourists were evaluated by convenience Anand Kapadia sampling. Secondary data collection was done from the existing review of literature and various Associate Professor, government sources to find out the existing infrastructure facilities. Road network, transport facility, Department of Architecture, water supply, Sewerage and solid waste management, accommodation facilities, recreational facilities Master of Urban and Regional and tourist inflow were included in secondary data collection. Planning, G.C Patel institute Results and data analysis: 79% of tourists’ purpose was purely religious and they all were Jains. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

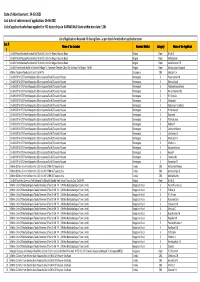

18.06.21.Final List of Applicants.Xlsx

Date of Advertisement : 24-03-2021 Last date of submission of application: 16-06-2021 List of applicants who have applied for RO dealerships in KARNATAKA State within due date: 1264 List of Applications Received till closing Date - as per details furnished on application cover Loc.N Name of the Location Revenue District Category Name of the Applicant ooo 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Girish D 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Ambikadevi G 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Sureshkumar R R 2 On LHS From Kerala Hotel In Biranholi Village To Hanuman Temple ,Ukkad On Kolhapur To Belgavi - NH48 Belgavi Open Mrutyunjaya Yaragatti 3 Within Tanigere Panchayath Limit On SH 76 Davangere OBC Santosh G H 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Pavan kumar M 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Dhana Gopal 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Prabhakaravardhana 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Narasimhamurthy 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC B V Srinivas 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Chalapathi 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Subramani Giridhar S 4 On LHS Of NH275 From -

Jain Worship

?} }? ?} }? ? ? ? ? ? Veer Gyanodaya Granthmala Serial No. 301 ? ? ? ? ? ? VEER GYANODAYA GRANTHMALA ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? This granthmala is an ambitious project of D.J.I.C.R. in ? ? ? ? which we are publishing the original and translated ? ? JAIN WORSHIP ? ? works of Digambar Jain sect written in Hindi, ? ? ? ? ? English, Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhramsh, ? ? ? ? ? -:Written by :- ? ? Kannad, Gujrati, Marathi Etc. We are ? ? Pragyashramni ? ? also publishing short story type ? ? ? ? books, booklets etc. in the ? ? Aryika Shri Chandnamati Mataji ? ? interest of beginners ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? and children. ? ? Published in Peace Year-2009, started with the inauguration of ? ? ? ? 'World Peace Ahimsa Conference' by the Hon'ble President of India ? ? -Founder & Inspiration- ? ? ? ? Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil at Jambudweep-Hastinapur on 21st Dec. 2008. ? GANINI PRAMUKH ARYIKA SHIROMANI ? ? ? ? ? ? ? SHRI GYANMATI MATAJI ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? -Guidance- ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Pragya Shramni Aryika Shri Chandnamati ? ? ? ? Mataji ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? -Direction- ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Peethadhish Kshullakratna Shri Moti Sagar Ji ? ? -: Published By :- ? ? ? ? Digambar Jain Trilok Shodh Sansthan ? ? -Granthmala Editor- ? ? ? ? Jambudweep-Hastinapur-250404, Distt.-Meerut (U.P.) ? ? ? ? Karmayogi Br. Shri Ravindra Kumar Jain ? Ph-(01233) 280184, 280236 ? ? ? All Rights Reserved for the Publisher ? ? E-mail : [email protected] ? ? ? ? Website : www.jambudweep.org ? ? ? ? ? ? Composing : Gyanmati Network, ? ? Chaitra Krishna Ekam ? ? ? First Edition Price Jambudweep-Hastinapur -

Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Datia Palace: Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith Dashavatar Temple: A Gupta-Era Wonder Deogarh’s Buddhist Caves Chanderi and its weaves The Beauty of Shivpuri Kalpi – A historic town I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi city also serves as a perfect base for day trips to visit the historic region around it. To the west of Jhansi lies the city of Datia, known for the beautiful palace built by Bundela ruler Bir Singh Ju Dev and the splendid Jain temple complex known as Sonagir. To the south, in the Lalitpur district of Uttar Pradesh lies Deogarh, one of the most important sites of ancient India. Here lies the famous Dashavatar temple, cluster of Jain temples as well as hidden Buddhist caves by the Betwa river, dating as early as 5th century BCE. Beyond Deogarh lies Chanderi , one of the most magnificent forts in India. The town is also famous for its beautiful weave and its Chanderi sarees. D A T I A P A L A C E Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand The spectacular Datia Palace, in Datia District of Madhya Pradesh, is one of the finest examples of Bundelkhand architecture that arose in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in the region under the Bundela Rajputs. Did you know that this palace even inspired Sir Edward Lutyens, the chief architect of New Delhi? Popularly known as ‘Govind Mahal’ or ‘Govind Mandir’ by local residents, the palace was built by the powerful ruler of Orchha, Bir Singh Ju Dev (r. -

THE DHRUVA STAMBHA / Vishnu Dhvaja (Qutub Minar) Wednesday, January 28, 2015 10:29 AM

THE DHRUVA STAMBHA / Vishnu Dhvaja (Qutub Minar) Wednesday, January 28, 2015 10:29 AM New Section 1 Page 1 New Section 1 Page 2 New Section 1 Page 3 New Section 1 Page 4 New Section 1 Page 5 New Section 1 Page 6 New Section 1 Page 7 New Section 1 Page 8 New Section 1 Page 9 New Section 1 Page 10 New Section 1 Page 11 New Section 1 Page 12 New Section 1 Page 13 New Section 1 Page 14 New Section 1 Page 15 New Section 1 Page 16 New Section 1 Page 17 THE DHRUVA STAMBHA / Vishnu Dhvaja (Qutub Minar) : : In 1961, some college students went with me to the Qutb Minar and e...ngaged an official guide, an M.A. in History. Questions and answers between our party and the Sarkari guide are given below in brief :- Q. What was the purpose of building this ‘MINAR’ ? A. Victory Tower. Q. Whose victory over whom ? A. Md. Ghori’s victory over Rai Pithaura (Prithvi Raj) Q. Where ? A. At Tarain near Panipat. Q. Why is the Victory Tower at Delhi ? A. Do not know. One gentleman from the visitors, a Lecturer in History in the University of Delhi, took up the threat and answered: The Victory Tower was commenced by Ghori because Delhi became his capital. Q. Objection, Sir! Ghori never had his capital at Delhi. His capital was at Ghazni. What logic is there in building the Victory Tower in Delhi ? A. Silence. Q. Even if the Minar was commenced by Ghori, its name ought to have been ‘GHORI MINAR’ and not ‘QUTB MINAR’. -

Vol. No. 99 September, 2008 Print "Ahimsa Times "

AHIMSA TIMES - SEPTEMBER 2008 ISSUE - www.jainsamaj.org Page 1 of 22 Vol. No. 99 Print "Ahimsa Times " September, 2008 www.jainsamaj.org Board of Trustees Circulation + 80000 Copies( Jains Only ) Email: Ahimsa Foundation [email protected] New Matrimonial New Members Business Directory PARYUSHAN PARVA Paryushan Parva is an annual religious festival of the Jains. Considered auspicious and sacred, it is observed to deepen the awareness as a physical being in conjunction with spiritual observations Generally, Paryushan Parva falls in the month of September. In Jainisim, fasting is considered as a spiritual activity, that purify our souls, improve morality, spiritual power, increase knowledge and strengthen relationships. The purpose is to purify our souls by staying closer to our own souls, looking at our faults and asking for forgiveness for the mistakes and taking vows to minimize our faults. Also a time when Jains will review their action towards their animals, environment and every kind of soul. Paryashan Parva is an annual, sacred religious festivals of the Jains. It is celebrated with fasting reading of scriptures, observing silence etc preferably under the guidance of monks in temples Strict fasting where one has to completely abstain from food and even water is observed for a week or more. Depending upon one's capability, complete fasting spans between 8-31 days. Religious and spiritual discourses are held where tales of Lord Mahavira are narrated. The Namokar Mantra is chanted everyday. Forgiveness in as important aspect of the celebration. At the end of Fasting, al will ask for forgiveness for any violence or wrong- doings they may have imposed previous year. -

Gujarat No. Tirth Name Moolnayak Bhagwan Contact

Gujarat No. Tirth Name Moolnayak Bhagwan Contact No. Shree Aaglod Tirth Shree Sumtinath / Manibhadraveer 02763-283734/283615 1 Shree Agastu Tirth Shree Sankeshwar Parshwanath 02666-232225/234049 2 Shree Ajahara Tirth Shree Ajahara Parshwanath 02875-221628/269355 3 Shree Ajitshanti Tirth Shree Ajitnath / Shree Shantinath 02767-252801 4 Shree Alipaur Tirth Shree Godiji Parshwanath 02634-237973 5 Shree Ayodhyapuram Tirth Shree Adinath Bhagwan 02841-281516/281636 6 Shree Bagwanda Tirth Shree Ajitnath Bhagwan 0260-2342313 7 Shree Banej Tirth Shree Parshwanath Bhagwan 0286-2243247/2241470 8 Shree Bauter Tirth Shree Adinath Bhagwan 02834-284159/220984 9 Shree Bhabhar Tirth Shree Munisuvrat Swami 02735-222486 10 Shree Bhadreshwar Tirth Shree Mahavir Swami 02838-283361/283382 11 Shree Bharol Tirth Shree Neminath Bhagwan 02737-226321 12 Shree Bharuch Tirth Shree Munisuvrat Swami 02642-570641 13 Shree Bhavnagar Tirth Shree Adinath Bhagwan 0278-2427384 14 Shree Bhiladiya Tirth Shree Bhiladiya Parshwanath 02744 - 232516 / 233130 15 Shree Bhoyani Tirth Shree Mallinath Bhagwan 079 - 23550204 16 Shree Bhuj Tirth Shree Chintamani Parshwanath 02832-224195 17 Shree Bhujpur Tirth Shree Chintamani Parshwanath 02838-240023 18 Shree Bodoli Tirth Shree Mahavir Swami 02665-222067 19 Shree Botad Tirth Shree Adinath Bhagwan 02849-251411 20 Shree Chanasma Tirth Shree Bhateva Parshwanath 02734-282325/223296 21 Shree Chandraprabhas Patan Shree Chandraprabhu Swami 02876-231638 22 Shree Charup Tirth Shree Shyamla Parshwanath 02766-284609/2277562 23 Shree Darbhavati -

Bhavnagar INDEX

Bhavnagar INDEX 1 Bhavnagar : A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations / Infrastructure 4 Support Infrastructure 2 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 Investment Opportunities 8 Annexure 2 1 3 Bhavnagar: A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Bhavnagar § Bhavnagar is located near the Gulf of Cambay in the Arabian Map1: District Map of Bhavnagar with Talukas Sea, a part of Saurashtra peninsula, in central part of Gujarat § Proximity of Bhavnagar with commercial districts of Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Surendranagar, and Amreli has made the district an important industrial location § The district has 11 talukas, of which the major ones are Bhavnagar (District Headquarter), Shihor, Talaja, Mahuva, Botad, Palitana, Ghogha and Vallabhipur 4 § Focus industry sectors: Diamond cutting & polishing, cement & gypsum, inorganic salt-based and marine chemicals, ship- Botad building, ship-repairs, oxygen, foundry, re-rolling, ceramics, Gadhda Umrala fabrication and food processing industries Vallabhipur Bhavnagar § World’s largest ship breaking yard is at Alang in the district Sihor Ghogha § Major tourist attractions in the district are Velavadar National Gariadhar Palitana Talaja park-Blackbuck sanctuary, Takhteshwar Temple, District Headquarter Talukas Mahuva Gaurishanker Lake, Jain Temples of Palitana and Talaja 4 Fact File 71.15o East (Longitude) Geographical Location 21.47o North (Latitude) Average Rainfall 605 mm Rivers Shetrunji, Ranghola and Kaludhar Area 8,628 sq. km. District Headquarter Bhavnagar Talukas 11 5 Population 24,69,630 (As per