Gagosian Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dina Wills Minimalist Art I Had Met Minimalism in the Arts Before Larry

Date: May 17, 2011 EI Presenter: Dina Wills Minimalist Art I had met minimalism in the arts before Larry Fong put up the exhibition in the JSMA Northwest Gallery, but I didn’t know it by name. Minimalism is a concept used in many arts - - theater, dance, fiction, visual art, architecture, music. In the early 80s in Seattle, Merce Cunningham, legendary dancer and lifelong partner of composer John Cage, gave a dance concert in which he sat on a chair, perfectly still, for 15 minutes. My husband and I remember visiting an art gallery in New York, where a painting that was all white, perhaps with brush marks, puzzled us greatly. Last year the Eugene Symphony played a piece by composer John Adams, “The Dharma at Big Sur” which I liked so much I bought the CD. I have seen Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” many times, and always enjoy it. I knew much more about theater and music than I did about visual art and dance, before I started researching this topic. Minimalism came into the arts in NYC in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, to scathing criticism, and more thoughtful criticism from people who believed in the artists and tried to understand their points of view. In 1966, the Jewish Museum in NY opened the exhibition “Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculpture” with everyone in the contemporary art scene there, and extensive coverage in media. It included sculpture by Robert Smithson, leaning planks by Judy Chicago and John McCracken, Ellsworth Kelly’s relief Blue Disc. A line of 137 straw-colored bricks on the floor called Lever by Carl Andre. -

Primordial Beginnings December 1, 2020 – January 9, 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Robert Smithson Primordial Beginnings December 1, 2020 – January 9, 2021 Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris and Holt/Smithson Foundation are pleased to announce the first exhibition of Robert Smithson at the Gallery, open from December 1, 2020 to January 9, 2021. Born in Passaic, New Jersey, Robert Smithson (1938-73) recalibrated the possibilities of art. For over fifty years his work and ideas have influenced artists and thinkers, building the ground from which contemporary art has grown. Primordial Beginnings will investigate Smithson’s exploration of, as he said in 1972, “origins and primordial beginnings, […] the archetypal nature of things.” This careful selection of works on paper will demonstrate how Smithson worked as, to use his words, a geological agent. He presciently explored the impact of human beings on the surface of our planet. The earliest works are fantastical science-fiction landscape paintings embedded in geological thinking. These rarely seen paintings from 1961 point to his later earthworks and proposals for collaborations with industry. Between 1961 and 1963 Smithson developed a series of collages showing evolving amphibians and dinosaurs. Paris in the Spring (1963) depicts a winged boy atop a Triceratops beside the Eiffel Tower, while Algae Algae (ca. 1961-63) combines paint and collage turtles in a dark green sea of words. For Smithson, landscape and its inhabitants were always undergoing change. In 1969 he started working with temporal sculptures made from gravitational flows and pours, thinking through these alluvial ideas in drawings. The first realized flow was Asphalt Rundown, in October 1969 in Rome, and the last, Partially Buried Woodshed, on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio in January 1970. -

2011-08-5 11Pasatiempo(Santa Fe,NM).Pdf

Michael Abatemarco I FQr The New Me)(ican STES EE NG The work of Nancy Holt --OP-- here IS no single critical essay followed by a seTies of plates m Nancy Hoil: Sfglulincs, puhlished by Unh<ersity of California PrcS5, it IS not a tYPical anist monograph. It is the kind of book you ca n open at any pO l!\l1O mar,·c! 31 the images orlhe artwork or absorb the text from any of a number of the book's contributors. There arc mull1plc ]X'rspcCI1\"e5 all Holt 's career here, olTered by editor Alcnaj. Williams. an hislOrians Lucy R. Uppard and Pamela M. Lee , artist Ines Schaber, and Mauhew Coolidge, direclOr of the Cemer fOT Land Usc Interpretation, Their observations create a well-rounded picture of Holt and her work. Further contributions include an [nlervicw with Emory University professor James Meyer and a detailed chronology of 11011'5 life by Humboldt Stale University professor Julia Alderson. Williams, a Columbia Universit)' doctoral (andid:ue, eontributes the preface, Introduction, and an esS3y, Siglll/incs a(wmpanics a traveling exhibit of the same name that started at Columbi~'s Wallach Art Gallery and wellt on to Gennan),. "Next it goes to Chicago." Hoh told PCUaficlII/X'. "thcn 01110 Boston, at Tufts University. [t goes to a few plates that arc associated wilh me one way or another, like Tufts is where I went to mllegc - they now ha~'e a rather large art gallcry. After that it comes to thc Santa Fc Art Institute next spring. and then onto Salt Lake City. -

Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels .Pdf

Nancy Holt Sun Tunnels, 1973–76 Internationally recognized as a pioneering work of Land art, Nancy Holt’s “The idea for Sun Tunnels became clear to me while I was in the desert watching notes Sun Tunnels (1973–76) is situated within a 40-acre plot in the Great Basin the sun rising and setting, keeping the time of the earth. Sun Tunnels can exist 1. Nancy Holt, “Sun Tunnels,” Artforum 15, no. 8 (April 1977), p. 37. 2. Ibid., p. 35. Desert in northwestern Utah. Composed of four concrete cylinders that are only in that particular place—the work evolved out of its site,” said Holt in a 3. Ibid. 18 feet in length and 9 feet in diameter, Sun Tunnels is arranged on the desert personal essay on the work, which was published in Artforum in 1977.1 She floor in an “x” pattern. During the summer and winter solstices, the four tunnels began working on Sun Tunnels in 1973 while in Amarillo, Texas. As her ideas Nancy Holt was born in 1938 in Worcester, Massachusetts, and was raised align with the angles of the rising and setting sun. Each tunnel has a different for the work developed, Holt began to search for a site in Arizona, New Mexico, in New Jersey. In 1960 she graduated from Tufts University in Medford, configuration of holes, corresponding to stars in the constellations Capricorn, and Utah. She was specifically looking for a flat desert surrounded by low Massachusetts. Shortly after, she moved to New York City and worked as an Columba, Draco, and Perseus. -

Collection Highlights Brochure

Arlington County Public Art Program Highlights Arlington County Public Art Program 1 Artists Nancy Holt 4 Ned Kahn 6 Cliff Garten 7 Jack Sanders, Robert Gay, Butch Anthony, Since 1979, when art was first negotiated as part of a private and Lucy Begg 8 development project, Arlington has been an innovator in the field of public art. Kendall Buster 10 Twenty years after the dedication in 1984 of Nancy Holt’s Bonifatius Stirnberg 12 internationally acclaimed Dark Star Park, and following the adoption of a Public Art Policy, the County Board approved Louis Comfort Tiffany 13 Arlington’s first public art master plan. This plan demonstrates Richard Chartier that public art can be a force for placemaking in the built environment, creating strong, meaningful connections between and Laura Traverso 14 people and places that are important to community and Jann Rosen Queralt 15 civic life. Arlington’s visionary plan for public art in the civic realm Butch Anthony 16 continues to guide projects initiated by both private developers Erwin Redl 17 and the County. Today, Arlington’s public art collection is comprised of nearly fifty works located throughout the County in urban corridors, public buildings, community centers, libraries, and neighborhood parks. It reflects the County’s values, diverse traditions, and civic pride. This brochure highlights selected past, current, and future artworks and provides an introduction to Arlington’s public art collection. A map on the inside of the back Public Art Program cover shows the locations of the art works. Arlington Cultural Affairs 2 Arlington County Public Art Program Holt created an enclosed, curvilinear space that is a contemplative counterpart to Dark Star Park, completed in 1984 and restored in 2002, was a the elevated traffic island and precedent setting project. -

Robert Morris in the 1980S*

Folds in the Fabric: Robert Morris in the 1980s* KEVIN LOTERY Nothing to do with a corpus: only some bodies. —Roland Barthes Artificer of the Uncreative By January of 1983, Robert Morris’s work had taken a decisive and shocking turn. In two concurrent exhibitions in New York, one at Leo Castelli Gallery and another at Sonnabend Gallery, Morris exhibited new large-scale, figurative reliefs and drawings produced over the past few years.1 While premonitions had appeared in installations at the end of the 1970s, these new works scandalized for their spectacular embrace of conventions of art-making that Morris had, for the most part, eliminated from his oeuvre. Architectural in scale and garish in their depictions of eviscerated human remains and postapocalyptic landscapes, these works, and the paintings that followed, seemed to bring back all the myths of painting the Neo-Expressionists of the late 1970s and early 1980s were just then resurrecting as so many bankable traits of a “zombie” masculine virility: expressivi- ty, figuration, and narrative, among them.2 Morris’s turn away from the strategies of abstraction, deskilling, and indeter- minacy that had guided his practice since the 1960s was so rapid, the reversals so all-encompassing, that little work has been done to square his activity in the ’80s with the earlier phases of his career. What, after all, could unite the theorist of anti-form and entropy—maker of process-based, anti-object folds, tangles, and mounds of felt and thread waste—with the painter of these Baroque, Neo- * This text benefited from conversations with Benjamin Buchloh and Jennifer Roberts. -

Nancy Holt Exhibition Brochure.Pdf

Nancy Holt In 1971 Nancy Holt placed several telescopic works around her loft studio in highlight light’s impact on our spatial consciousness. The rarely seen, room-sized sun, moon, and human eye. In pushing the conventions of sculpture and New York City’s West Village. Locators, as she called them—vertical, steel pipe installations Holes of Light (1973) and Mirrors of Light I (1974) are pivotal to proposing a participatory experience in these early works, the circle is sculptures of varying heights with welded crosspieces through which one may understanding her ideas concerning perceptual experience. Profound in scale and actuated, and Holt’s ideas on the concretization of perception—focus, light, look—focused perspective on a detail of Holt’s daily environment. She secured involving rigorous calculations, both works are architectonic structures in which and space—are revealed. Immediately upon realizing Holes of Light and the Locators to the floor and windowsills, positioning them to direct one’s interior projected light is channeled within a complex spatial experience. Holes of Light Mirrors of Light I, Holt began to explore these concepts in the landscape perspective on exterior focal points, such as a pair of windows across the court- does so by projecting light through circular holes to investigate principles of and created Sun Tunnels (1973–76), her iconic work in the geographic yard or an exhaust pipe on the roof below. While seemingly simple in execution, directionality and shadow, while Mirrors of Light I utilizes circular mirrors and expanse of Utah’s Great Basin Desert. With Sun Tunnels, Holt looked above this act of using industrial plumbing pipes to shape one’s visual perspective rays of light to examine the laws of reflection. -

Marian Goodman Gallery Robert Smithson

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY ROBERT SMITHSON Born: Passaic, New Jersey, 1938 Died: Amarillo, Texas, 1973 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Robert Smithson: Time Crystals, University of Queensland, BrisBane; Monash University Art Museum, MelBourne 2015 Robert Smithson: Pop, James Cohan, New York, New York 2014 Robert Smithson: New Jersey Earthworks, Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, New Jersey 2013 Robert Smithson in Texas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas 2012 Robert Smithson: The Invention of Landscape, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, Unteres Schloss, Germany; Reykjavik Art Museum, Reykjavik, Iceland 2011 Robert Smithson in Emmen, Broken Circle/Spiral Hill Revisited, CBK Emmen (Center for Visual Arts), Emmen, the Netherlands 2010 IKONS, Religious Drawings and Sculptures from 1960, Art Basel 41, Basel, Switzerland 2008 Robert Smithson POP Works, 1961-1964, Art Kabinett, Art Basel Miami Beach, Miami, Florida 2004 Robert Smithson, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York 2003 Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A Fragment of a Greater Fragmentation, Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada Rundown, curated by Cornelia Lauf and Elyse Goldberg, American Academy in Rome, Italy 2001 Mapping Dislocations, James Cohan Gallery, New York 2000 Robert Smithson, curated by Eva Schmidt, Kai Voeckler, Sabine Folie, Kunsthalle Wein am Karlsplatz, Vienna, Austria new york paris london www.mariangoodman.com MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Robert Smithson: The Spiral Jetty, organized -

Patricia Johanson, Dennis Oppenheim, and Athena Tacha, Who Had Started Executing Public Commissions for Large Urban Sites.” - Wikipedia DEFINITION

INTRODUCTION SITE SPECIFIC INSTALLATION DEFINITION “Site-specific art is artwork created to exist in a certain place. Typically, the artist takes the location into account while planning and creating the artwork. The actual term was promoted and refined by Californian artist Robert Irwin, but it was actually first used in the mid-1970s by young sculptors, such as Patricia Johanson, Dennis Oppenheim, and Athena Tacha, who had started executing public commissions for large urban sites.” - Wikipedia DEFINITION Site-specific or Environmental art refers to an artist's intervention in a specific locale, creating a work that is integrated with its surroundings and that explores its relationship to the topography of its locale, whether indoors or out, urban, desert, marine, or otherwise. - Guggenheim Museum PATRICIA JOHANSON Johanson is an artist known for her large-scale art projects that create aesthetic and practical habitats for humans and wildlife. DENNIS OPPENHEIM Dennis Oppenheim was a conceptual artist, performance artist, earth artist, sculptor and photographer. DENNIS OPPENHEIM “LIGHT CHAMBER” DENVER JUSTICE CENTER ATHENA TACHA, PUTNAM COLLEGE Athena Tacha is best known in the fields of environmental public sculpture and conceptual art. She has also worked extensively in photography, film and artists’ books. ROBERT SMITHSON “SPIRAL JETTY” GREAT SALT LAKE, UT Smithson's central work is Spiral Jetty - an earthwork sculpture constructed in April 1970. ROBERT SMITHSON “SPIRAL JETTY” GREAT SALT LAKE, UT CRISTO JAVACHEFF & JEANNE-CLAUDE DE GUILLEBON Christo and Jeanne-Claude were a married couple who created environmental works of art. For two weeks, the Reichstag in Berlin was shrouded with silvery fabric, shaped by the blue ropes, highlighting the features and proportions of the imposing structure. -

Holt/Smithson Foundation Oral History Archive Deedee Halleck Interviewed by Lisa Le Feuvre February 1, 2019

Holt/Smithson Foundation Oral History Archive DeeDee Halleck interviewed by Lisa Le Feuvre February 1, 2019 Lisa Le Feuvre is Executive Director of Holt/Smithson Foundation. DeeDee Halleck is a media activist, founder of Paper Tiger Television, and co-founder of Deep Dish Satellite Network. This interview was recorded on February 1, 2019 at DeeDee Halleck’s home in New York City. DeeDee Halleck describes how she first met Nancy Holt in 1973, and their subsequent friendship and collaboration on Nancy Holt’s films. This transcript is a lightly edited version of the conversation, correcting names and dates where needed, as well as removing redundant words. Keywords Amarillo Ramp Halleck Pine Barrens Art Park John Weber Gallery Serra Desert Leukemia Sky Mound Dwan Massachusetts Smithson Film Matta-Clark Solar Web Finkel Mono Lake Sound Fiore New Jersey Sun Tunnels Floating Island New Mexico Video Greenwich Street Niagara Copyright: Holt/Smithson Foundation Lisa Le Feuvre This is Lisa Le Feuvre conducting an interview on February the 1st, 2019 for Holt/Smithson Foundation's oral history project, with DeeDee Halleck. And thank you, DeeDee, for agreeing to talk to us. How did you first meet Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson? DeeDee Halleck I never met Robert Smithson but I met Nancy on the evening after a group of friends of Smithson's had been to a funeral, and then they went to Virginia Dwan's. And then they all went to this club, which was a transvestite club on, I think it was 4th Street, but it was quite strange. I had never been to such a club. -

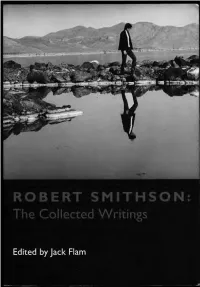

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim.