Orthodox Clergy of Oltenia During the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Medieval Urban Economy in Wallachia

iANALELE ŞTIIN łIFICE ALE UNIVERSIT Ăł II „ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA” DIN IA ŞI Tomul LVI Ştiin Ńe Economice 2009 ON THE MEDIEVAL URBAN ECONOMY IN WALLACHIA Lauren Ńiu R ĂDVAN * Abstract The present study focuses on the background of the medieval urban economy in Wallachia. Townspeople earned most of their income through trade. Acting as middlemen in the trade between the Levant and Central Europe, the merchants in Br ăila, Târgovi şte, Câmpulung, Bucure şti or Târg şor became involved in trading goods that were local or had been brought from beyond the Carpathians or the Black Sea. Raw materials were the goods of choice, and Wallachia had vast amounts of them: salt, cereals, livestock or animal products, skins, wax, honey; mostly imported were expensive cloth or finer goods, much sought after by the local rulers and boyars. An analysis of the documents indicates that crafts were only secondary, witness the many raw goods imported: fine cloth (brought specifically from Flanders), weapons, tools. Products gained by practicing various crafts were sold, covering the food and clothing demand for townspeople and the rural population. As was the case with Moldavia, Wallachia stood out by its vintage wine, most of it coming from vineyards neighbouring towns. The study also deals with the ethnicity of the merchants present on the Wallachia market. Tradesmen from local towns were joined by numerous Transylvanians (Bra şov, Sibiu), but also Balkans (Ragussa) or Poles (Lviv). The Transylvanian ones enjoyed some privileges, such as tax exemptions or reduced customs duties. Key words: regional history; medieval trade; charters of privilege; merchants; craftsmen; Wallachia JEL classification: N93 1. -

Agentia Pentru Protec Tia Mediului Gorj 10058/16.12.2015

AGENTIA PENTRU PROTECTIA MEDIULUI GORJ No. 76, Unirii Street, Tg-Jio, Gorj, cod 2l0143 E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: 0253215384; Fax: 0253212892 Agentia pentru Protec tia Mediului Gorj Nr.: 10058/16.12.2015 Catre Primariile: Calnic, Farcasesti, Negomir, Slivilești, Ciuperceni, Motru, Matasari, Dragotes t i, Negomir, Catunele, Urdari, Plopsoru, Balteni. In atentia Domnilor Primari Referitor la: Solicitarea a 104 persoane care s-au constituit ”Public afectat” privind organizarea dezbaterilor publice pentru carierele apartinand urmatoarelor unitati miniere: UMC Pinoasa, UMC Rosia, UMC Tismana I, ti ana I, UMC Tismana Il, UMC Rosiuta, UMC Lupoaia, UMC Jilt Nord. UMC Jilt Sud_, UMC Pesteana Nord, UMC Pesteana Sud, Stimati Domni, Stimate Doamne, Urmare a solicitarii unui numar de 104 persoane, care s-au constituit ”Public afectat”, cu privire la organizarea dezbaterilor publice pentru carierele sus mentionate, solicitare inregistrata la APM Gorj cu nr. 10058/03.12.2015, va transmitem raspunsul (Anunt) in aceasta solicitare, pe care va rugam sa il afisati la sediul primariilor din comunele dumneavoastra. Va solicitam acest lucru pentru a face cunoscut raspunsul nostru persoanelor semnatare, care nu si-au prezentat adresele de corespondenta. Va multumim anticipat. Director Executiv AGENJIA PENT Ministerul Mediului, Apelor si Padurilor Agentia Nationala pentru Protectia Mediului Agentia pentru Protectia Mediului Gorj Nr.: 10058/16.12.2015 Catre: „Public afectat”, semnatarii solicitarii transmise la APM Gorj, din comunele: Calnic, Farcasesti, Negomir, Slivilesti, Ciuperceni, Motru, Matasari, Dragotești, Negomir, Catunele, Urdari, Plopsoru, Balteni. In atentia: Publicului afectat “ Solicitarea a 104 persoane care s-au constituit ”Public afectat” privind organizarea dezbaterilor publice pentru carierele apartinand urmatoarelor unitati miniere: UMC Pinoasa, UMC Rosia, UMC Tismana I, UMC Tismana II, UMC Rosiuta, UMC Lupoaia, UMC Jilt Nord, UMC Jilt Sud, UMC Pesteana Nord, UMC Pesteana Sud. -

The Landscape and Biodiversity Gorj - Strengths in the Development of Rural Tourism

Annals of the „Constantin Brancusi” University of Targu Jiu, Engineering Series , No. 2/2016 THE LANDSCAPE AND BIODIVERSITY GORJ - STRENGTHS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF RURAL TOURISM Roxana-Gabriela Popa, University “Constantin Brâncuşi”, Tg-Jiu, ROMANIA Irina-Ramona Pecingină, University “Constantin Brâncuşi”, Tg-Jiu, ROMANIA ABSTRACT:The paper presents the context in which topography and biodiversity Gorj county represent strengths in development of rural tourism / ecotourism. The area is characterized by the diversity of landforms, mountains , hills, plateaus , plains, meadows , rivers , natural and artificial lakes, that can be capitalized and constitute targets attraction. KEY WORDS: landscape, biodiversity, tourism, rural 1. PLACING THE ENVIRONMENT Gorj County has a significant tourism GORJ COUNTY potential, thanks to a diversified natural environment , represented by the uniform Gorj County is located in the south - west of distribution of relief items , dense river Romania, in Oltenia northwest. It borders the network , balanced and valuable resources for counties of Caras Severin , Dolj, Hunedoara, climate and landscape area economy. Mehedinţi and Vâlcea. Gorj county occupies an area of 5602 km2, which represents 2.3% 2. GORJ COUNTY RELIEF of the country. Overlap almost entirely of the middle basin of the Jiu , which crosses the The relief area includes mountain ranges, hills county from north to south. From the and foothill extended a hilly area in the administrative point of view , Gorj county is southern half of the county. Morphologically, divided into nine cities, including 2 cities Gorj county has stepped descending from (Targu- Jiu- county resident and Motru), cities north to south. Bumbeşti -Jiu, Novaci, Rovinari, Targu Mountains are grouped in the north of the Cărbuneşti, Tismana, Turceni, Ticleni, 61 county and occupies about 29 % of the common and 411 village (Figure 1.) county. -

Retea Scolara

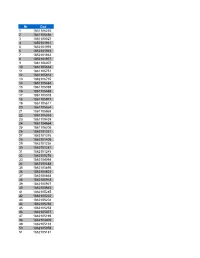

Nr Cod 1 1831106235 2 1841105456 3 1861100027 4 1852101941 5 1852101959 6 1852101923 7 1852101932 8 1852101977 9 1881106007 10 1861105638 11 1861105751 12 1861105914 13 1882106735 14 1861105484 15 1861105398 16 1861105588 17 1861100018 18 1861105977 19 1861105611 20 1861105864 21 1861105968 22 1861105353 23 1861105439 24 1861104664 25 1861106205 26 1862101331 27 1862101376 28 1862101408 29 1862101236 30 1862101281 31 1862101245 32 1862105276 33 1862104094 34 1862100488 35 1862100895 36 1862100823 37 1862100868 38 1862100918 39 1862100927 40 1862100945 41 1862105285 42 1862105222 43 1862105204 44 1862105294 45 1862105258 46 1862105077 47 1862105199 48 1862104809 49 1862105163 50 1862105059 51 1862105181 52 1861104596 53 1861105543 54 1862104777 55 1862102938 56 1862102567 57 1862103586 58 1862102635 59 1862106431 60 1862102047 61 1862105136 62 1862103134 63 1862100497 64 1862104058 65 1862102671 66 1862103835 67 1862104203 68 1862100606 69 1862103826 70 1862102282 71 1862103785 72 1862100651 73 1862103966 74 1862100122 75 1862102083 76 1862100434 77 1862101679 78 1862104239 79 1862101661 80 1862103283 81 1862103844 82 1862100981 83 1862103238 84 1862103912 85 1862103618 86 1862100407 87 1862100303 88 1862102133 89 1862100416 90 1862101091 91 1862103179 92 1862103532 93 1862103627 94 1862103609 95 1862103306 96 1862104379 97 1862102531 98 1862103107 99 1862104402 100 1862104483 101 1862101584 102 1862101566 103 1862102617 104 1862105095 105 1862104013 106 1862104949 107 1862103342 108 1862106485 109 1862102196 110 1862103021 111 1862104456 -

Journalists Visit Romania

Journalists Visit Romania By Jim Thompson As you know, many members of The Alliance gathered in Romania a few weeks ago. It was a wonderful event and very different from the usual meetings and gatherings involving FIJET. It was a week free of politics, meetings and intrigue. There was no complaining about schedules, hotel accommodations or meeting times. There were no ceremonies, boring speeches or demands on our time. Instead, it was a gathering of journalists with time to exchange ideas, get to know about the many wonders of Romania, talk about our profession and discuss ways of cooperating in the future. Our host, Victor Radulescu, did an excellent job of organizing the event that included a near perfect blending of interesting locations, information for articles and meetings with officials. Aside from a few minor occasions, we managed to stay with the schedule without feeling pushed or pressured and without insulting our hosts by not arriving as promised. In a testament to his skills as an organizer and manager, Victor managed to show us the very best of Gorj County and southern Romania. He did all of this while juggling a demanding schedule of producing and editing two hour long programs for The Money Channel (Romanian Television). He and Iulia Mladin worked constantly to produce an excellent program on our visit and on the current workings of the Romanian tourism efforts. A special thanks goes to Victor for his kindness, his efficiency and for all of his efforts! We began our visit (October 10-16) at the wonderful Phoenicia Grand Hotel in Bucharest. -

Date Calitative Despre Școlile Gimnaziale Gorj

Date calitative despre școlile gimnaziale Gorj Media Media diferenţelor Media mediilor la Număr mediilor de mediei mediilor Maximul Minimul Cod Judeţ evaluarea școli absolvire evaluarea diferenței diferenței naţională cls. 5-8 națională - absolvire 5-8 GJ 115 8,43 7,02 -1,58 -3,13 -0,12 Național 5.867 8,59 6,79 -2,16 -7,11 0,26 Diferenţa mediei Media mediilor Media mediilor la mediilor Rang după Cod Număr de Rang după Judeţ Nume Mediu de absolvire cls. 5- evaluarea evaluarea diferență pe Şcoală elevi diferență pe țară 8 naţională națională - județ absolvire 5-8 GJ 112 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "C-TIN. SAVOIU" TG-JIU 143 U 8,91 8,79 -0,12 1 40 GJ 113 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI" TIRGU-JIU 50 U 8,76 8,64 -0,12 2 41 GJ 155 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA BARBATESTI 25 R 8,36 8,15 -0,22 3 61 GJ 207 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA PRIGORIA 23 R 8,03 7,70 -0,32 4 110 GJ 115 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "GHEORGHE TATARASCU" TIRGU-JIU 99 U 8,72 8,33 -0,39 5 142 GJ 104 COLEGIUL NATIONAL "TUDOR VLADIMIRESCU" TG-JIU 46 U 9,28 8,87 -0,40 6 151 GJ 135 LICEUL TEHNOLOGIC TURCENI 77 U 8,84 8,40 -0,43 7 168 GJ 110 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "SF.NICOLAE" TIRGU-JIU 63 U 8,69 8,21 -0,48 8 195 GJ 177 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA DUMBRAVENI, CRASNA 16 R 8,21 7,68 -0,53 9 224 GJ 188 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA HUREZANI 16 R 8,51 7,98 -0,53 10 229 GJ 103 COLEGIUL NATIONAL "SPIRU HARET" TG-JIU 52 U 8,86 8,31 -0,55 11 242 GJ 178 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA RADOSI, CRASNA 9 R 8,40 7,76 -0,64 12 302 GJ 218 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA SLIVILESTI 43 R 8,18 7,51 -0,67 13 332 GJ 105 LICEUL VOCATIONAL DE MUZICA SI ARTE PLASTICE "C-TIN BRAILOIU" TG-JIU -

Introduceţi Titlul Lucrării

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Annals of the University of Craiova - Agriculture, Montanology, Cadastre Series Analele Universităţii din Craiova, seria Agricultură – Montanologie – Cadastru (Annals of the University of Craiova - Agriculture, Montanology, Cadastre Series) Vol. XLIII 2013 RESEARCH ON THE IDENTIFICATION AND PROMOTION OF AGROTURISTIC POTENTIAL OF TERRITORY BETWEEN JIU AND OLT RIVER CĂLINA AUREL, CĂLINA JENICA, CROITORU CONSTANTIN ALIN University of Craiova, Faculty of Agriculture and Horticulture Keywords: agrotourism, agrotourism potential, agrotouristic services, rural area. ABSTRACT The idea of undertaking this research emerged in 1993, when was taking in study for doctoral thesis region between Jiu and Olt River. Starting this year, for over 20 years, I studied very thoroughly this area and concluded that it has a rich and diverse natural and anthropic tourism potential that is not exploited to its true value. Also scientific researches have shown that the area benefits of an environment with particular beauty and purity, of an ethnographic and folklore thesaurus of great originality and attractiveness represented by: specific architecture, traditional crafts, folk techniques, ancestral habits, religion, holidays, filled with historical and art monuments, archeological sites, museums etc.. All these natural and human tourism resources constitute a very favorable and stimulating factor in the implementation and sustained development of agritourism and rural tourism activities in the great and the unique land between Jiu and Olt River. INTRODUCTION Agritourism and rural tourism as economic and socio-cultural activities are part of protection rules for built and natural environment, namely tourism based on ecological principles, became parts of ecotourism, which as definition and content goes beyond protected areas (Grolleau H., 1988 and Annick Deshons, 2006). -

Gorj, Săptămâna 13 Mai – 19 Mai 2019

ÎNTRERUPERI PROGRAMATE – JUDEŢUL GORJ, SĂPTĂMÂNA 13 MAI – 19 MAI 2019 Distribuţie Oltenia execută lucrări programate în reţelele electrice pentru creşterea gradului de siguranţă şi continuitate în alimentarea cu energie electrică a consumatorilor, precum şi a îmbunătăţirii parametrilor de calitate ai energiei electrice distribuite. Distribuţie Oltenia anunţă întreruperea furnizării energiei electrice la consumatorii casnici şi agenţii economici, astfel: Interval orar Data Localitatea Zona de întrerupere de întrerupere 09:00 - 15:00 Stejari PTA Hurezanii de Stejari nr. 2 - sat Hurezanii de Stejari 08:00 - 15:00 Stoina PTA Stoina nr. 1 - Sat Stoina - parțial 13.05 09:00 - 15:00 Turburea PTA Sipot - sat Sipot, PTA Turburea de Sus - sat Turburea de Sus 09:00 - 15:00 Țînțăreni PTA Florești nr. 5 - sat Florești - parțial 09:00 - 15:00 Telești PTA Telești nr. 2 - sat Telești - parțial 14.05 08:00 - 15:00 Tismana PTA Vînăta - sat Vînăta PTAB 36, PTA 260, PTA 52, Cartier Tișmana, stăzile: Merilor, Microcolonie, Călăraș, Meteor și Aleea Călăraș, PTA 09:00 - 17:00 Târgu Jiu 230, străzile: Barajelor și Jiului 09:00 - 15:00 Alimpești PTA Alimpești nr 1 - sat Alimpești - parțial 15.05 09:00 - 15:00 Baia de Fier PTA Baia de Fier nr. 1 - sat Baia de Fier - parțial 09:00 - 15:00 Țînțăreni PTA Florești nr. 6 - sat Florești - parțial 16.05 PTAB 36, PTA 260, PTA 52, Cartier Tișmana, stăzile: Merilor, Microcolonie, Călăraș, Meteor și Aleea Călăraș, PTA 09:00 - 17:00 Târgu Jiu 230, străzile: Barajelor și Jiului 09:00 - 15:00 Mătăsari PTA Brădet nr. 2 - sat Brădet 17.05 09:00 - 15:00 Stănești PTA Polata - sat Polata 09:00 - 15:00 Stănești PTAB Obreja - sat Obreja, PTAB Călești - sat Călești, PTA Măzăroi - sat Măzăroi, PTA Crețu (terț) Lucrările pot fi reprogramate în situaţia în care condiţiile meteo sunt nefavorabile. -

Romanian Traditional Musical Instruments

GRU-10-P-LP-57-DJ-TR ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS Romania is a European country whose population consists mainly (approx. 90%) of ethnic Romanians, as well as a variety of minorities such as German, Hungarian and Roma (Gypsy) populations. This has resulted in a multicultural environment which includes active ethnic music scenes. Romania also has thriving scenes in the fields of pop music, hip hop, heavy metal and rock and roll. During the first decade of the 21st century some Europop groups, such as Morandi, Akcent, and Yarabi, achieved success abroad. Traditional Romanian folk music remains popular, and some folk musicians have come to national (and even international) fame. ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC Folk music is the oldest form of Romanian musical creation, characterized by great vitality; it is the defining source of the cultured musical creation, both religious and lay. Conservation of Romanian folk music has been aided by a large and enduring audience, and by numerous performers who helped propagate and further develop the folk sound. (One of them, Gheorghe Zamfir, is famous throughout the world today, and helped popularize a traditional Romanian folk instrument, the panpipes.) The earliest music was played on various pipes with rhythmical accompaniment later added by a cobza. This style can be still found in Moldavian Carpathian regions of Vrancea and Bucovina and with the Hungarian Csango minority. The Greek historians have recorded that the Dacians played guitars, and priests perform songs with added guitars. The bagpipe was popular from medieval times, as it was in most European countries, but became rare in recent times before a 20th century revival. -

VII.1 FORESTIER Insertie Absolventi Nivel 2 RP an Scolar 2010-2011 1

Unitatea şcolară: Colegiul Tehnic Forestier TABEL NOMINAL CU ABSOLVENŢII ANULUI DE COMPLETARE PROMOŢIA 2011 Urmează Adresa de domiciliu a absolventului Liceul Mediul de Numele şi tehnologic rezidenţă Adresa prenumele in anul al Nr. Unitatea Numele Calificarea unităţii absolventului (în școlar 2011- absolventu Daca își crt. şcolară tatălui dobândită Judeţul/ Oraş/ şcolare ordine alfabetică în 2012 la lui (U- Satul Strada Nr. Bloc Scară Etaj Ap. Telefon continuă Sectorul Comună cadrul şcolii) învățământ urban; R- studiile de zi rural) da / nu 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Colegiul Mecanic 1 Tehnic Calea lui TraianAndreescu 195-197 Adrian Rm. Vâlcea CătălinVasile Da R Vâlcea Muereasca Găvăneşti 0762096800 Da auto Forestier Colegiul Mecanic 2 Tehnic Calea lui TraianAngelescu 195-197 Bogdan Rm. VâlceaGheorghe Da U Vâlcea Băile OlăneştiOlăneşti Podului 1 0860112583 Da auto Forestier Colegiul Mecanic 3 Tehnic Calea lui TraianBălan 195-197 Andrei Rm. Grigore VâlceaAlexandru Da R Vâlcea Nicolae BălcescuCorbii din Vale 0751808375 Da auto Forestier Colegiul Mecanic 4 Tehnic Calea lui TraianBogiu 195-197 Dumitru Rm. Andrei VâlceaDumitru Da R Vâlcea Galicea Teiu 0745917669 Da auto Forestier Colegiul 5 Tehnic Calea lui TraianBroboană 195-197 Diana Rm. Elena VâlceaNicolae Pădurar Da R Vâlcea Frînceşti Viişoara 0748639375 Da Forestier Colegiul 6 Tehnic Calea lui TraianCălin 195-197 Anton Rm.Alexandru Vâlcea Anton Pădurar Da U Vâlcea Brezoi Eroilor 219 0745918633 Da Forestier Colegiul 7 Tehnic Calea lui TraianCăprescu 195-197 Vasilica Rm. Vâlcea CameliaVirgil Pădurar Da R Vâlcea Roşiile Păsărei 0765979572 Da Forestier Colegiul 8 Tehnic Calea lui TraianChirca 195-197 Anamaria Rm. -

Unitati Afiliate GORJ 25.03.2021

LISTA UNITATILOR CARE PREGATESC SI SERVESC/ LIVREAZA MESE CALDE SI CARE ACCEPTA TICHETE SOCIALE PENTRU MESE CALDE JUDETUL GORJ Nr. crt. Localitate Denumire unitate partenera Adresa unitatii partenere/punctului de lucru care ofera mese calde Nr. telefon 1 ALBENI RESTAURANT & CATERING LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 2 ALBENI ARINDIRAZ SRL -RESTAURANT ALBENI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 3 ALBENI FAIGRASSO COM SRL livrare ALBENI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0733422422 4 ALIMPESTI RESTAURANT& CATERING ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 5 ALIMPESTI 3 AXE RESTAURANT ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0722684062 6 ALIMPESTI 3 AXE RESTAURANT CIUPERCENI DE OLTET LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 722684062 7 ALIMPESTI ARINDIRAZ SRL -RESTAURANT ALIMPESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 8 ANINOASA RESTAURANT & CATERING ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0729129831 9 ANINOASA DKD INFINITI GROUP SRL CATERING ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765885500 10 ANINOASA FAIGRASSO COM SRL livrare ANINOASA LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0733422422 11 ARCANI PENSIUNEA LUMINITA TRAVEL RESTAURANT ARCANI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765275015 12 ARCANI PENSIUNEA LA MOARA CATERING ARCANI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0747377377/0726696633 PENSIUNEA LUMINITA TRAVEL RESTAURANT 13 ARCANI SANATESTI LIVRARE LA DOMICILIU 0765275015 14 ARCANI RESTAURANT LA MARCEL STR. PRINCIPALA NR.328, 217025 0720245414 15 BAIA DE FIER PENSIUNE TURISTICA SUPER PANORAMIC ZONA RANCA, CORNESUL MARE 0732281990/0733998811 16 BAIA DE FIER RESTAURANT HOTEL ONIX STATIUNEA RANCA STATIUNEA RANCA, CORNESUL MARE 0744614743 17 BAIA DE FIER TOBO PENSIUNE -

The Export Potential of the Muntenia Oltenia Vineyard Area

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series V: Economic Sciences • Vol. 9 (58) No. 2 - 2016 The export potential of the Muntenia Oltenia vineyard area 1 Oana BĂRBULESCU Abstract: The work that begins with the presentation of the Muntenia Oltenia wine region intends to identify the reasons underlying the small share of exports in the total production of wine made in this area and to formulate some proposals which could represent in the future solutions to improve the trade balance of the vineyard sector. In order to know the barriers that prevent wine exports, qualitative marketing research was conducted with 8 managers of vineyard areas. After analyzing the information obtained it could be concluded that in order to give more coherence and consistency to their wines, in order to promote more effectively on foreign markets and finally in order to benefit from the increased exports, wine producers should associate depending on the wine regions they belong to. Key-words: export, wine-growing areas, promotion, association, producer 1. Introduction The Muntenia Oltenia vineyard area stretching from west to east along the meridian Subcarpathians including the South West of Oltenia, the vineyards in Severin, the Segarcea, the Getic plateau, the terraces of Olt, the piedmont hills of Argeş and the last ramifications of the Curvature Subcarpathians represented by the hills of Buzău. The region is specialized in the production of white, rosé and red, dry, semi- dry or semisweet wines of superior quality. The varieties that are grown mainly here are: Feteasca, Black Drăgăşani, Novac, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot noir, Royal Feteasca, Pinot Gris, Italian Riesling, Sauvignon, Romanian Tămâioasă, Muscat Ottonel etc.