Pete Seeger and the Turning Season of the US Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger(1922 - 2013) Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger

Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger(1922 - 2013) Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger Beacon - Toshi Aline Ohta Seeger 1922-2013 Born in Munich, Germany in 1922 to an American mother and a Japanese father, Toshi Seeger, loving wife to Pete Seeger, died peacefully at home at age 91 on the 9th of July 2013. Toshi's mother gave birth July 1st, 1922 while traveling in Germany. She entered this country at six months of age and took up residence with her mother, Virginia Harper Berry from Washington D.C. and father, Takashi Ueda Ohta from Shikoku, Japan. She lived in Greenwich Village and Woodstock NY in the 1920s, 30s , and 40s. Her parents and half sister Aline Dixon were a part of the theatre community and she grew up surrounded by art and theatre. Toshi attended The Little Red School House in New York City and graduated from the High School of Music and Art in 1940. She was a community volunteer, festival organizer, writer, filmmaker, road manager, potter, loving mother, grandmother, great grandmother and aunt. She met her husband, folk singer and activist, Pete Seeger in 1939. They married in NYC in 1943, while Pete was on leave from the army. Toshi passed away eleven days shy of their 70th wedding anniversary. Toshi and Pete were partners in every sense of the word. They collaborated on everything from building their log cabin and organizing festivals big and small. This was made possible only through Toshi's tireless work, creative mind and meticulous organizational skills. Toshi served on the New York State Council of the Arts and marched with Dr. -

Pete Seeger and Intellectual Property Law

Teaching The Hudson River Valley Review Teaching About “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” –Steve Garabedian Lesson Plan Introduction: Students will use the Hudson River Valley Review (HRVR) Article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” as a model for an exemplary research paper (PDF of the full article is included in this PDF). Lesson activities will scaffold student’s understanding of the article’s theme as well as the article’s construction. This lesson concludes with an individual research paper constructed by the students using the information and resources understood in this lesson sequence. Each activity below can be adapted according to the student’s needs and abilities. Suggested Grade Level: 11th grade US History: Regents level and AP level, 12th grade Participation in Government: Regents level and AP level. Objective: Students will be able to: Read and comprehend the provided text. Analyze primary documents, literary style. Explain and describe the theme of the article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” in a comprehensive summary. After completing these activities students will be able to recognize effective writing styles. Standards Addressed: Students will: Use important ideas, social and cultural values, beliefs, and traditions from New York State and United States history illustrate the connections and interactions of people and events across time and from a variety of perspectives. Develop and test hypotheses about important events, eras, or issues in United States history, setting clear and valid criteria for judging the importance and significance of these events, eras, or issues. -

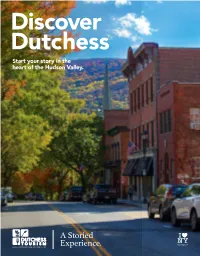

Destination Guide 2020 All Phone Numbers Are in (845) Area Code Unless Otherwise Indicated

ELCOMEELCOME Dutchess County delivers the rugged, natural beauty of the Hudson Valley, world renowned dining, and a storied history of empire builders, visionaries and artists. Take a trip here to forge indelible memories, and discover that true wealth is actually the exceptional experiences one shares in life. Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, Red Hook Table of Contents Events . 2 Eastern Dutchess . .. 30 Groups, Meetings Explore Dutchess by Community . 4 Where to Stay . 38 & Conferences . 46 Northern Dutchess . 6 Places to Eat . 42 Accessible and LGBTQ Travel . 47 Central Dutchess . 14 Colleges . 44 About Dutchess . 48 Southern Dutchess . 22 Weddings . 45 Transportation & Directions . 49 Dutchess Tourism, Inc. is On the cover: Main Street Beacon accredited by the Destination Marketing Accreditation Program (DMAP) of DutchessTourism.com #MyDutchessStory Destinations International. Notes: To the best of our knowledge, the information in this guide is correct as of March 1, 2020. Due to possible changes, we Custom publishing services provided by recommend that you contact a site before visiting. This guide lists only those facilities that wish to be included. Listings do not represent an endorsement. The programs provided by this agency are partially funded by monies received from the County of ChronogramMedia Dutchess. This travel guide is published by Dutchess Tourism, Inc., 3 Neptune Rd., Suite A11A, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601, the County of Dutchess, in cooperation with the New York State Department of Economic Development and the I Love New York 314 Wall Street, Kingston, NY 12401 campaign. ® I LOVE NEW YORK is a registered trademark and service mark of the New York State Department of Economic ChronogramMedia.com Development; used with permission. -

Seeger Fest: Opening Night Will Be an Evening Alongside Pete Seeger’S Beloved Hudson River at Pier 46 in Manhattan

Seeger Fest: Opening Night will be an evening alongside Pete Seeger’s beloved Hudson River at Pier 46 in Manhattan. The Chapin Sisters, Kristen Graves and others will sing a one-hour concert with the backdrop of the setting sun. Then there will be a screening of Pete Seeger: The Power of Song, an Emmy-award winning documentary featuring Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt and Others. Bring dinner and a picnic blanket and celebrate Pete Seeger on a Hudson River pier. Arrive early. Seating is limited. 7:30 PM - Thursday, July 17, 2014 - Hudson River Park’s Pier 46 at Charles Street, Greenwich Village, New York, NY http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/events/pete-seeger-the-power-of-song Memorial Service for Pete Seeger is the only official memorial service for Pete Seeger. Friends and family come together to remember their friend, neighbor and mentor at a local Hudson Valley theater where Seeger played hundreds of times. Pete 7:00 PM – Friday, July 18, 2014 – Bardavon Opera House, 35 Market Street, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 Tickets are available for in-person pickup at the Bardavon in Poughkeepsie. http://www.bardavon.org/event_info.php?id=751&venue=bardavon South Bronx Seeger Fest is a free festival on the Bronx River that includes hip-hop, reggae and folk music, boat rides and free food provided by Lola’s Tacos. Artists include Jasiri X, the reggae group Rootz Revelators, The Owens Brothers, The Chapin Sisters, Kristen Graves, The Tony Lee Thomas Band and Julia Haltigan plus surprise guests. The event is hosted by Rocking the Boat. -

2018 CLEARWATER FESTIVAL 1 Letter from the DIRECTOR

“ ON EARTH cares for your trees and creates naturalized landscapes with attention to detail, deep knowledge, and sound experience.” – Steven A. Knapp ISA & Connecticut Certified Arborist & Forester; Certified Pesticide Applicator NYS DEC, #C3809834 & CT DEP, #62871; Certified Ornamental Horticulture, Forestry and Plant Science Teacher PROPERTY DESIGN & INSTALLATION: stone patios, steps large tree planting walkways, retaining walls vegetable, berry, herb gardens outdoor entertainment areas arbors, pergolas, firepits rustic outdoor furniture milled with portable sawmill To get started, call, email from your trees or text us for a TREES & SHRUBS: complimentary estimate! pruning, trimming, shaping take downs, emergency work cabling, bracing tel: 845-621-2227 planting, transplanting cel/txt: 914-490-3134 stump grinding, removal [email protected] lot clearing, mulching, firewood plant health care www.onearthplantcare.com Greg Lawler Greg TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letter From the Director 15 Handcrafters’ Village 34 Food Vendors About Clearwater Green Living Expo 3 18 36 Field & River Activities 4 Raffles 20 Volunteer 38 Zero Waste 5 Membership Village 22 Children’s Area 42 Stage Schedules 6 Sloop Clearwater 24 Artisanal Food & Farm Market Festival Performers 7 Letter from the 46 Board President 26 The Clearwater Store 56 Patron Fish 8 Education 27 Marketplace 58 Sloop Clubs 10 Environmental Action 28 Access 60 Who’s Who 12 Climate Solutions 30 Activist Area 13 Working Waterfront 32 Map 62 Behind the Scenes 2018 CLEARWATER FESTIVAL 1 Letter from the DIRECTOR over for me when I step down. She sang act locally.” Please consider talking with “The Water is Wide” at Circle of Song last your family and friends about what you year. -

Pete Seeger and Folk Song Activism in the Cold War Era, 1948 - 1972

“Wasn’t that a Time:” Pete Seeger and Folk Song Activism in the Cold War Era, 1948 - 1972 By Christine Anne Kelly B.A. in History, May 2011, Messiah College A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 19, 2013 Thesis directed by Edward D. Berkowitz Professor of History For Pete who guarded well our human chain as long as sun did shine ii Table of Contents Dedication………………………………………………………………………............... ii I. Introduction: “John Henry”……………………………………………………………. 1 Seeger the Steel Driving Man……………………………………………………. 1 Historiographical Review………………………………………………………. 15 Interventions……………………………………………………………………. 22 II. “If I Had a Hammer:” 1948 – 1960………………………………………………….. 27 The Weavers……………………………………………………………………. 27 Riot in Peekskill………………………………………………………………… 28 The Work of the Weavers………………………………………………………. 30 The Folk Process………………………………………………………............... 32 Folk Song to Transcend Social Boundaries: Possibilities and Limits………….. 33 The Weavers and the Red Scare………………………………………............... 35 Seeger Goes Solo……………………………………………………………….. 39 Audience Participation………………………………………………………….. 46 Trouble Appears: The House Un-American Activities Committee…………….. 52 III. “Die Gedanken Sind Frei:” 1961 – 1965…………………………………………… 57 A Song of Freedom……………………………………………………............... 57 Seeger on Trial………………………………………………………………….. 58 Civil Rights: Learning a New Tune…………………………………………….. 65 World Tour……………………………………………………………………… -

Folklife Center News, Volume 29, Nos. 1-2 (Northern Ireland, Seegers

Folklife Center News AMERIC A N F O L K L I F E C ENTER FAMILY VALUES FROM SCARBOROUGH FAIR ALL THROUGH THE NORTH, SEEGER STYLE: TO CAPITOL HILL: AS I WALKED FORTH: BOARD OF TRUSTEES Librarian Appointees: Tom Rankin, Chair, North Carolina Jane Beck, Vice-chair, Vermont Donald Scott, Nevada Kojo Nnamdi, District of Columbia Congressional Appointees: Daniel Botkin, California C. Kurt Dewhurst, Michigan Mickey Hart, California Dennis Holub, South Dakota William L. Kinney Jr., South Carolina Marlene Meyerson, New Mexico In the keynote address of Since his youth, Paul A recap of the fascinating Charlie Seemann, Nevada Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Massachusetts 3 AFC’s historic Seeger Fam- 12 Simon has been fascinated 18 and entertaining series of Presidential Appointees: lectures, concerts and symposia ily Tribute in March 2007, Neil V. with folklore. In April 2007,in Mary Bomar, Director, National Park Service Rosenberg examines the legacy of preparation for winning the Library celebrating the culture of Northern Lisette M. Mondello, Assistant Secretary for a family crucial to American music of Congress’s Gershwin Award for Ireland, held at AFC in May, 2007. Public and Governmental Affairs, Department of Veterans Affairs and folklore. Popular song, he visited AFC. Ex Officio Members James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress AMERIC A N F O L K L I F E C ENTER Cristián Samper, Acting Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution The American Folklife Center was created in 1976 by the U.S. Congress to “preserve and present Dana Gioia, Chairman, National Endowment American folklife” through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference for the Arts service, live performance, exhibition, publication, and training. -

The Windmill Movie

Montage 7hj"Xeeai"Z_l[hi[Yh[Wj_edi 18 Open Book 19 Music,Taken Personally 20 Off the Shelf 23 Diaghilev and His Geniuses 24 Mnemonic Masks 26 Chapter and Verse XWi[Zedj^[Z_Whoe\ W 9ebed_Wb c_Zm_\[ j^Wj)&&j^7dd_l[hiWho Kd_l[hi_jo Fhe\[iieh BWkh[bJ^WjY^[hKbh_Y^ [nfekdZ[Z_d^[h'//& Xeeae\j^[iWc[dWc[$ O[j j^[h[ mWi ed[ ÓbcHe][himWid[l[h WXb[jeÓd_i^"Z[if_j[ (& o[Whi e\ i^eej_d] WdZYebb[Yj_d]\eejW][" ckY^ e\ _j Y[dj[h[Z ed^_iemd\Wc_boWdZ Filmmaker j^[>Wcfjedijemde\ The Windmill Movie Alexander Olch MW_diYejj"m^[h[j^[o in his studio ^WZWikcc[h^eki[$ on Mott Street ?jmWib[\jje^_iijk# in Manhattan, JmeÓbccWa[hiYebbWXehWj[WYheiij^[]kb\X[jm[[db_\[WdZZ[Wj^$ doors away Z[dj7b[nWdZ[hEbY^ from where his Ê// He][hi jWk]^j 9H7?= B7C8;HJ Xo mentor, Richard ÓbccWa_d]\ehcWdo Rogers, lived and worked. o[WhiWj>WhlWhZWdZ ^[bWj[\_bccWa[hH_Y^# \hecWH[lebkj_ed '//'" m^_Y^ \ebbemi mWi Z_h[Yjeh e\ j^[ WhZHe][hiÊ,-";Z$C$Ê-&"m^e f^eje]hWf^[hIkiWdC[_i[bWi";Z$C$Ê-'" <_bcIjkZo9[dj[hjeYh[Wj[J^[M_dZc_bb Z_[Ze\YWdY[h_d(&&'WjW][+-" Wii^[h[jkhdijeD_YWhW]kW'&o[WhiW\j[h Cel_[\hecj^[c_b[ie\kdYkjÓbcWdZ mWiWfWii_edWj[WdZfheZkY# ZeYkc[dj_d]j^[IWdZ_d_ijWel[hj^hem l_Z[eb[\jX[^_dZ$ÇJ^[h[mWiWl[ho]eeZ j_l[Whj_ij$>_iZeYkc[djWho e\IecepW$J^[h[m[h[b_j[hWhofehjhW_ji h[Wiedm^o^[b[jj^_ied[]e"ÈiWoiEbY^$ TÓbcihWd][\hecGkWhho'/-&"Wib_Y[#e\# b_a[^_i'/..M_bb_Wc9WhbeiM_bb_Wci"Zed[ Ç:_YaYecfb[j[Z'.Óbci"Xkjj^_imWi b_\[beeaWjoekj^iZ_l_d]"im_cc_d]"WdZ \ehF8I1gk_haoÓbcib_a[((,#',/&'/.*" j^[edboed[j^Wjh[Wbbo]Wl[^_cjhekXb[" bekd]_d]WhekdZWX[Wkj_\kbWXWdZed[Z WÇc_d_cWb_ijieWfef[hWÈZhWm_d]ed X[YWki[j^[ikX`[YjmWiedj^[ej^[hi_Z[ heYagkWhho_dGk_dYo"CWiiWY^ki[jji" Wo[WhÊimehj^e\c[iiW][iedHe][hiÊi e\j^[YWc[hW$È?d\WYj"EbY^ÊiceijXWi_Y m_j^WbWj[#'/,&iheYaiekdZjhWYaWdZ Wdim[h_d]cWY^_d[1WdZj^[^_ijeh_YWb Z[Y_i_edmWiÓ]kh_d]ekjj^Wjj^[Óbc beec_d]i^WZemie\L_[jdWc"jeF_Yjkh[i h[#[dWYjc[dje\7C_Zm_\[ÊiJWb['//," mWiWXekjHe][hi"dejMW_diYejj1_jÊiW F^eje]hWf^XoJob[h>_Yai%J^[D[mOehaJ_c[i >WhlWhZCW]Wp_d['- Magazine, Inc. -

A Naturalist in Show Business

A NATURALIST IN SHOW BUSINESS or I Helped Kill Vaudeville by Sam Hinton Manuscript of April, 2001 Sam Hinton - 9420 La Jolla Shores Dr. - La Jolla, CA 92037 - (858) 453-0679 - Email: [email protected] Sam Hinton - 9420 La Jolla Shores Dr. - La Jolla, CA 92037 - (858) 453-0679 - Email: [email protected] A Naturalist in Show Business PROLOGUE In the two academic years 1934-1936, I was a student at Texas A & M College (now Texas A & M University), and music was an important hobby alongside of zoology, my major field of study. It was at A & M that I realized that the songs I most loved were called “folk songs” and that there was an extensive literature about them. I decided forthwith that the rest of my ;life would be devoted to these two activities--natural history and folk music. The singing got a boost when one of my fellow students, Rollins Colquitt, lent me his old guitar for the summer of 1935, with the understanding that over the summer I was to learn to play it, and teach him how the following school year.. Part of the deal worked out fine: I developed a very moderate proficiency on that useful instrument—but “Fish” Colquitt didn’t come back to A & M while I was there, and I kept that old guitar until it came to pieces several years later. With it, I performed whenever I could, and my first formal folk music concert came in the Spring of 1936, when Prof. J. Frank Dobie invited me to the University of Texas in Austin, to sing East Texas songs for the Texas Folklore Society. -

Pete Seeger Redaction Pete Seeger Est Mort Ce Lundi 27 Janvier 2014

https://www.contretemps.eu In Memoriam : Pete Seeger redaction Pete Seeger est mort ce lundi 27 janvier 2014. Il avait 94 ans. Il y aurait trop à en dire. Un livre n’y suffirait pas. Quelques lignes désordonnées en donneront peut-être une idée, et donneront peut-être envie de mieux le connaître. Pete Seeger restera sans doute d’abord dans les mémoires comme le principal acteur de la musique populaire américaine connue sous le nom de folksong. De la fin des années 1930 du XXe siècle aux débuts du XXIe, il en aura été l’inlassable porte-voix, l’idole, l’inspirateur et la référence de celles et ceux qui, de Joan Baez à Bruce Springsteen, en passant par Peter, Paul & Mary et Bob Dylan auront contribué à faire vivre ce répertoire. Certaines chansons restent attachées à son nom. Ainsi If I Had A Hammer, chanson composée avec son ami Lee Hayes en défense des dirigeants communistes poursuivis par la « chasse aux sorcières » : Si j’avais un marteau, je forgerais la liberté… Ainsi Where Have All The Flowers Gone, reprise par toute une génération pour protester contre la guerre. Ainsi ces autres chansons anti-guerre que sont Waist Deep In The Big Muddy, Last Train To Nuremberg ou Bring’Em Home ! Ainsi le célèbre hymne des droits civiques We Shall Overcome, pour lequel Seeger avait repris, en le transformant, un vieux gospel, suivant le processus courant de la création folklorique. Ainsi Turn, Turn, Turn, chanson de sagesse inspirée de l’Ecclésiaste D’autres chansons, dont il n’était pas l’auteur, ont été popularisées par Pete Seeger, comme le Little Boxes de Malvina Reynolds : Ou encore le What did You Learn At School ? de Tom Paxton : Mais plus généralement, c’est le grand répertoire folk que Seeger a immortalisé, des chansons anonymes issues du tréfonds du peuple à celles de son ami Woody Guthrie. -

A Guide to the Staten Island Friends of Clearwater Collection 1977-2010

A Guide to the Staten Island Friends of Clearwater Collection 1977-2010 Overview of the Collection Collection Number: SIM-31 Title: Staten Island Friends of Clearwater Creators: James Scarcella Dates: 1977-2010 Extent: .18 cubic feet Abstract: Staten Island Friends of Clearwater was formed to support the mission of Hudson River Sloop Clearwater and to further environmental protection efforts on Staten Island. Administrative Information Preferred Citation The Natural Resources Protective Association Collection, Archives & Special Collections, Department of the Library, College of Staten Island, CUNY, Staten Island, New York. Acquisition This collection was donated to the College of Staten Island Archives and Special Collections by James Scarcella on December 3, 2014. Processing Information The collection was processed in 2015 and the inventory prepared by James Kaser. ________________________________________________________________ Restrictions: Access Access to this record group is unrestricted. Copyright Notice The researcher assumes full responsibility for compliance with laws of copyright. Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be discussed with the Coordinator of Archives & Special Collections. ________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The bulk of this collection consists of materials produced by Hudson Sloop Clearwater, Inc., a non-profit organization founded by folk singer Pete Seeger with his wife Toshi Seeger in 1966. The organization played a crucial role in the reclamation of the Hudson River utilizing a sailing sloop, named Clearwater, and an annual music and environmental festival as public education tools, as well as practicing a wide range of activism and advocacy. A group of Staten Islanders formed Staten Island Friends of Clearwater to support the larger organization and practice advocacy and public education on Staten Island to protect and improve environmental conditions of the Hudson estuary surrounding Staten Island. -

Pete Seeger Dead: Folk Singer and Activist Dies at 94

The weather conditions are not available. change weather location News Sports Music Radio TV My Region More Watch Listen Search SeaSrcighn Up | Log In IN THE NEWS ■ Liberal senators ■ Data privacy World ■ Rob Ford ■ Stephen Hawking CBC News Home World Canada Politics Business Health Arts & Entertainment Technology & Science Community Weather Video World Photo Galleries Pete Seeger dead: folk singer and activist dies at 94 Seeger became famous as a member of The Weavers quartet, formed in 1948 The Associated Press Posted: Jan 28, 2014 1:54 AM ET | Last Updated: Jan 29, 2014 6:14 PM ET Stay Connected with CBC News Mobile Facebook Podcasts Twitter Alerts Newsletter American troubadour, folk singer and activist Pete Seeger died Monday Jan. 27, 2014, at age 94. Here, Seeger Must Watch performs on stage during the 2013 Farm Aid concert in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Here's a look at his life in pictures. (Hans Pennink/The Associated Press) 1 of 11 Pete Seeger, the banjo-picking troubadour who sang for migrant 'They crucified me:' Ads for 'the drunk guy in workers, college students and star-struck presidents in a career that Ukrainian protester the back of the room' introduced generations of Americans to their folk music heritage, died (graphic images) 5:53 Monday at the age of 94. 3:25 Super Bowl ad review Pete Seeger dies at 94 2:28 Seeger's grandson, Kitama Cahill-Jackson said his grandfather died at Dmytro Bulatov says he and a primer on the was kidnapped on Jan. theory and practice of New York Presbyterian Hospital, where he'd been for six days.